Download Chapter 270KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

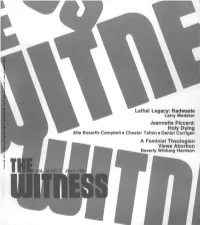

Holy Dying a Feminist Theologian Views Abortion

publication. and reuse for required Permission Lethal Legacy: Radwaste DFMS. / Larry Medsker Church Jeannette Piccard: Holy Dying Episcopal Alia Bozarth-Campbell • Chester Talton • Daniel Corrigan the of A Feminist Theologian Views Abortion Archives Beverly Wiidung Harrison 2020. Copyright the Left had by then turned its attention opposition to abortion is a matter of a to stopping the U.S. involvement in prurient and anti-woman bigotry. Vietnam. There was little energy and They are apparently unaware (or less vision remaining with which to choose to keep their readers unaware) tackle the tenacles of sexism. of the large numbers of feminist, Haitt and Heyward contend that progressive, and peaceful Christians sexism was the "volatile, explosive, and who oppose abortion because it is decisive" issue of the 1980 elections, violent — it is bloody — and it snuffs out precipitating the defeat of President human lives. LETTERS Carter and sundry U.S. Senators. Or is this perhaps another of those Special pleading alone would pick that "dirty little secrets"? TnTTTHll Q issue from the complex fabric of factors Ms. Juli Loesch affecting voters in late 1980. The Prolifers for Survival economy, foreign affairs, political Erie, Pa. publication. organization, money, to say nothing of regional and state-by-state differences and contributed to the liberal debacle (Iowa has never in the century re-elected a Heyward, Hiatt Respond reuse Authors' Ire Emotional Democratic Senator). And to suggest Dr. Kastner is precisely correct in his for The essay of the Revs. Suzanne Hiatt that Jimmy Carter was in the same final observation that the Right has and Carter Heyward on "Right-Wing liberal circles on women's issues as capitalized on the weariness and Religion's 'Dirty Little Secret' " Senators McGovern and Bayh is bizarre required weakness of the Left. -

AEM Update Department of Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics Winter 2014 Visiting Fulbright Scholar Reflects on Experience

AEM Update Department of Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics Winter 2014 Visiting Fulbright Scholar Reflects on Experience Visiting Fulbright Scholar Bela Distinguished McKnight University Professor Gary Balas. “We Takarics joined the University’s De- are always looking to advance our research and see this as a partment of Aerospace Engineering great opportunity to do so. The department has had a strong and Mechanics in December 2013. connection with the Hungarian Academy of Science. We truly Working as a Research Associate, benefit from the exchange of scholars between our two institu- Takarics’ interests include reduced tions. ” order modeling with a focus on aeroservoelastic vehicles and how their models vary across the flight envelope, and the application of Only three months into his stay, Takarics is highly motivated a Tensor Product model based control design to aeroservoelastic ve- by the work he has accomplished, claiming that his research hicles. Now three months into his five-month stay, Takarics says his is on the “fast track in terms of development” and expressing experience thus far has been “absolutely amazing.” interest in extending his stay for an additional four months. When asked what is attributing to this success, Takarics Prior to applying for the Fulbright Scholar explains that working in the laboratory and Program, Takarics received a Masters in Me- Since joining the AEM collaborating with other researchers has been chanical Engineering and a PhD in Control team, my research has been incredibly helpful. Theory from Budapest University of Technolo- “ gy and Economics. In 2010 he began working on the fast track in terms of “In Hungary, theoretical research can be as a Research Fellow to develop a robust and development. -

Don Piccard 50 Years & BM

July 1997 $3.50 BALLOON LIFE EDITOR MAGAZINE 50 Years 1997 marks the 50th anniversary for a number of important dates in aviation history Volume 12, Number 7 including the formation of the U.S. Air Force. The most widely known of the 1947 July 1997 Editor-In-Chief “firsts” is Chuck Yeager’s breaking the sound barrier in an experimental jet—the X-1. Publisher Today two other famous firsts are celebrated on television by the “X-Files.” In early Tom Hamilton July near the small southwestern New Mexico town of Roswell the first aliens from outer Contributing Editors space were reported to have been taken into custody when their “flying saucer” crashed Ron Behrmann, George Denniston, and burned. Mike Rose, Peter Stekel The other surreal first had taken place two weeks earlier. Kenneth Arnold observed Columnists a strange sight while flying a search and rescue mission near Mt. Rainier in Washington Christine Kalakuka, Bill Murtorff, Don Piccard state. After he landed in Pendelton, Oregon he told reporters that he had seen a group of Staff Photographer flying objects. He described the ships as being “pie shaped” with “half domes” coming Ron Behrmann out the tops. Arnold coined the term “flying saucers.” Contributors For the last fifty years unidentified flying objects have dominated unexplainable Allen Amsbaugh, Roger Bansemer, sighting in the sky. Even sonic booms from jet aircraft can still generate phone calls to Jan Frjdman, Graham Hannah, local emergency assistance numbers. Glen Moyer, Bill Randol, Polly Anna Randol, Rob Schantz, Today, debate about visitors from another galaxy captures the headlines. -

Jeannette (Ridlon) Piccard (1895 – 1981) 1St Woman in Stratosphere

Jeannette (Ridlon) Piccard (1895 – 1981) 1st Woman in Stratosphere 1st Female Episcopal Priest Jeannette (Ridlon) Piccard, daughter of pioneering orthopedic surgeon Dr. John Ridlon (1852 – 1936) and his wife Emily Robinson (1859 – 1942) was herself a pioneer on two fronts. Jeannette was born Jan. 5, 1895 in Chicago, the 8th of 9 children. She had a twin sister Beatrice who died at age 3. Jeanette grew up in Chicago, summering at a family home Rhuddlans on the Cliff in Newport, RI. See the Dr. John Ridlon Father of Orthopedic Surgery entry in this collection for more information on Jeannette’s Ridlon & Robinson families. Jeannette received a Bachelors degree in Philosophy and Psychology from Bryn Mawr College in 1918 and in 1919 a Masters degree in Organic Chemistry from the University of Chicago. It was there that she met her future husband Jean Felix Piccard (1884 – 1963), a Swiss native who was teaching chemistry at that school. They married in 1919 and subsequently relocated to Switzerland where all three of their sons were born. In 1926 they were back living in the US where they continued to live for the remainder of their lives (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and finally Minnesota). Jean and his twin brother Auguste who lived in Belgium were both pioneers in their balloon flights into the stratosphere, Auguste having done his first in Germany in 1931. In 1934 Jean and Jeannette Piccard flew a balloon to 57,559 feet into the stratosphere, making Jeannette the first woman in the world to enter the stratosphere. Prior to that flight she had been the first woman in the US licensed as a balloon pilot. -

VOL. 63, NO. 10 OCTOBER, 1980 Married Clergy, Separated Churches • Robert L. Dewitt on the Ordination of Gays • Louie Crew T

publication. and reuse for required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. Copyright VOL. 63, NO. 10 OCTOBER, 1980 Married Clergy, Separated Churches • Robert L. DeWitt On the Ordination of Gays • Louie Crew The Spirit of Anglicanism • William J. Wolf agrees that both Matthew and Mark as would start that way — and I know quite well as Luke say thaf'only Jesus and the a few who are serious about their life in Twelve sat or recli ned at the table." Were the church. I think they would they lying to back up some chauvinistic acknowledge their limited under- idea? standing of church politics and get on No, Miss Piccard, you may have a D.D. with proposing a working agenda. Even but you also have a clouded mind unable more to the point, they understand that to accept the facts as they are, and not they have a lot of work to do inside their what you would like them to be. own limited, human institutions The Rev. Brian J. Stych, L.Th. (unions) and assume that other people Northcote, Auckland have the same task. New Zealand What is it that causes Christian liberals and progressives to be so preachy about the labor movement? We Challenges Piccard Piccard Responds know very little about the best work that publication. I was doubtful about writing to you, but I would like to thank the Rev. Brian J. they do among the poor and and my wife feels I should, so I must reply to Stych, L.Th. for bringing out another unorganized. -

Smith, Ann Robb

The Archives of Women in Theological Scholarship The Burke Library (Columbia University Libraries) At Union Theological Seminary, New York Finding Aid for Ann Robb Smith Papers, 1971 - 2004 Finding Aid prepared by: Ruth Tonkiss Cameron, May 2006 Additional material prepared by: Patricia LaRosa, July 2006, revised by Ruth Tonkiss Cameron, July 2008 Summary Information Creator: Ann Robb Smith Title: Ann Robb Smith Papers Inclusive dates: 1971 - 2004 Bulk Dates: 1974 - 1975 Abstract: Member of the Women’s ordination planning group prior to the ordination of the first women Episcopal Priests at the Church of the Advocate, Philadelphia, July 29, 1974 [the Philadelphia 11]; lay presenter for the ordination of Sue Hiatt; ordained Asst at Church of the Advocate. Contains newspaper clippings, articles, correspondence, minutes of planning meetings, reports, statements, sermons, service sheets, and the ordination service sheet for the Philadelphia 11, July 29, 1974. Size: 2 boxes, 1 linear ft. Storage: On-site storage Repository: The Burke Library Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Email: [email protected] AWTS: Ann Robb Smith Papers 2 Administrative Information Provenance: Ann Robb Smith donated her papers to the Archives of Women in Theological Scholarship in October 1999 with another addition in 2006. Some of the material donated consists of records from the Women’s Ordination Now support group. Access: Archival papers are available to registered readers for consultation by appointment only. Please contact archives staff by email to [email protected], or by postal mail to The Burke Library address on page 1, as far in advance as possible Burke Library staff is available for inquiries or to request a consultation on archival or special collections research. -

Eleven Women Ordained Priests in Philadelphia Christian Conscience?

Special Issue, 60 cents August 25, 1974 Eleven Women Ordained Priests In Philadelphia publication. and reuse Christian Conscience? for The recent ordination of a number of women to the priesthood was done in only partial compliance with the established procedures for ordinations. The required irregular character of that action draws attention to those internal laws of the church, the canons. Challenges to received institutions make lawyers of us all. The canons concerning the ministry have all been written in terms of "he," Permission "him," and "his." It could be argued that the language of the canons was open to the construction that "he" might mean "human being" or baptized person." DFMS. / But over the generations this understanding of the intent of the canons was never tested. Seminaries were all-male enclaves; the diaconate, presbyterate, Church and episcopate were filled exclusively by men; and few people seem to have thought these things should be different than they were. After some years of consciousness-raising on the part of individuals and Episcopal the community, women were, by express action of General Convention, the admitted to the diaconate. Their call by God and their competence in ministry of was and is undeniable. Then, in the fall of 1973, a motion to admit women to the priesthood was Archives presented to the General Convention. It received a majority in the House of Bishops and was approved by a majority of the deputies. However, since 2020. divided delegations are counted as negative, the negative votes plus the divided votes outnumbered the affirmative votes, and the action failed in the Copyright House of Deputies. -

Holy Women, Holy Men Celebrating the Saints

Holy Women, Holy Men Celebrating the Saints Additional Commemorations September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Church Publishing Inc. March 28 James Solomon Russell I O God the font of resurrected life, we bless thee for the courageous witness of thy deacon, James Solomon Russell, whose mosaic ministry overcame all adversities: Draw us into the wilderness and speak tenderly to us there so that we might love and worship thee as he did, assured in our legacy of saving grace through Jesus Christ, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, for ever and ever. Amen. II God, font of resurrected life, we bless you for the courageous witness of your deacon, James Solomon Russell, whose mosaic ministry vaulted over adversity; allure us into the wilderness and speak tenderly to us there so that we might love and worship you as he did, sure of our legacy of saving grace through Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, always and ever. Amen. 1 Chronicles 29:10-13 Psalm 126 1 Timothy 6:11-16 John 14:8-14 Preface of Dedication of a Church James Solomon Russell was born into slavery on December 20, 1857, near Palmer Springs, Virginia. He became known as the father of St. Paul’s College (one of the three historically Black Episcopal Colleges) and was the founder of numerous congregations, a missionary, and a writer. He was the first student of St. Stephen’s Normal and Theological Institute (which later became the Bishop Payne Divinity School) in Petersburg, Virginia. In 1888, one year after his ordination as a priest in the Episcopal Church, Russell and his wife Virginia opened St. -

Gemini V Circles Earth 120 Times in 8 Days, Returns Record Breaking Crew Safe and Sound After Traveling 3,338,200 Miles Through Space in Seven Days

VOL. 4, NO. 23 MANNED SPACECRAFTCENTER,HOUSTON, TEXAS SEPTEMBER3, 1965 Gemini V Circles Earth 120 Times In 8 Days, Returns Record Breaking Crew Safe And Sound After traveling 3,338,200 miles through space in seven days. 22 hours and 56 minutes, the Gemini V spacecraft and crew floated to a landing in West Atlantic waters, ending their record breaking flight at 6:55 a.m.. CST, August 29. Bearded Astronauts L. Gor- you tired'?", Cooper replied, hope that both of you along with don CooperJr. and Charles Con- "No, are you'?", your fellow astronauts, can red Jr. landed some 90 miles Cooper and Conrad ,*'ere accept some invitations to share west ofthe prime recovery ship, scheduled to have arrived here your achievements with the the aircraft carrier USS Lake yesterday for six more day's of peoples of other lands." Champlain. after making 120 debriefings before they come out "This Flight of Gemini V was revolutions around _ seclusion. The post-flight a journey of peace by men of just under eight da_pl|ss conference wit h _ace, the Pres,dent .sa,d. ,lls was cut one re,VJj[l_o.g shorf_onauts is schgd_l'e_ for_g__ c_e_sr_J concms,on is a nap e because ofa stc_/r_c_flled l-I_i_Je-'-gr__very plus eleve_a_ -mt_fi_ntfor mankind and a fitting cane Bets-:,, in th_l_aA_-_ .j '_ration of the eigll_dligh_-_ g_r_tlm'ty for us to renew our cry area '{ >#7_ J._F._7ooper and Co_n_dk_'__s __-gg _ cont,nue our search A he copter from tlie-ai_-_ffat man is capable'[email protected]_ f,_world in whicn peace re,gns carrier picked _blb: , e two as_jo- I gh: to the Moon _8 justice prevails." nauts and carfi_'-_l_n to _h_- * _ is about the same length of The Gemini. -

Session Weekly March 26, 1999 Vol. 16, Number 12

A Nonpartisan Publication of the Minnesota House of Representatives ♦ March 26, 1999 ♦ Volume 16, Number 12 HF2183-HF2291 Session Weekly is a nonpartisan publication of the Minnesota House of Representatives Public Information Office. During the 1999-2000 Legislative Minnesota House of Representatives • March 26, 1999 • Volume 16, Number 12 Session, each issue reports daily House action between Thursdays of each week, lists bill introductions and upcoming committee meeting schedules, and pro- vides other information. The publication Reflections is a service of the Minnesota House. One could say it all started in Minnesota. No fee. On March 21, two men touched down in Egypt, miles past the point of completely circling the Earth for the first time in a hot-air balloon. To subscribe, contact: One of them was Swiss psychiatrist Bertrand Piccard, the grand-nephew Minnesota House of Representatives of Drs. Jean and Jeannette Piccard of Minnesota. Jean and Jeannette also Public Information Office made aviation history. In 1934, Jean accompanied his wife as she piloted 175 State Office Building a balloon to a point in the stratosphere that, at 57,979 feet, was higher than St. Paul, MN 55155-1298 had ever been reached before. By so doing, they broke the record held by Jean’s twin (651) 296-2146 or brother, Auguste. His record of 53,152 feet was set in 1932. 1-800-657-3550 Auguste Piccard also designed a pressurized balloon gondola — and his grandson TTY (651) 296-9896 Bertrand and fellow balloonist Brian Jones drew on that concept for their balloon trip around the earth. -

Official Publication of the International Women Pilots Association

OFFICIALHiBSSnEius PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS ASSOCIATION CANADIAN 99s. Canadian women pilots and 99 chapters will be featured in an issue next spring that will be similar to the one on international women pilots in Jan/Feb of 1981. Please send information, articles and pictures to Roberta Taylor ATTN: 99 NEWS Contributors and/or Rosella Bjornson. A PERSPECTIVE ON HISTORY: 99 Chapter News Reporters contributions are heartily encouraged. We are fortunate to have several guest editors June 1982. We’d like to celebrate some of 1. Deadline: Material must reach 99 Head who will be developing the theme material our old-timers and share with everyone their quarters by 1st of month. for these issues and if you wish to experiences, advice and everything else 2. All material must be typed, double contribute, materials may be sent directly to they have to offer. Contact the women in spaced. them or to 99 Headquarters. Please let us your chapter/area who began their asso 3. Try to limit report to one type written know right away if you can plan to help. ciation with aviation in its early years and page. Include news about chapter proj capture some of their favorite anecdotes ects, activities, meetings, outstanding WOMEN IN SPACE, edited by Beverly and incidents for us. Naturally, we’d love to achievements or items of note about in Fogle, is scheduled for November ’81. Any have some pictures, too. (We will return dividual members, etc. as timely and ap information, pictures, articles you have on them if requested.) Elaine Levesque is propriate.