Midterm Evaluation of Engaged, Educated, and Empoyered Ethiopian Youth E4y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Background of the Network

Background of the Network Although interventions against HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia began after the first case was identified in 1984, the establishment of associations of people living with HIV/AIDS didn't happen until the mid 1990s. The involvement of these associations and some other organizations engaged in the fight against the pandemic to the curtain of stigma and discrimination against PLWHA has showed encouraging results and gradually decreased these and other HIV/AIDS related problems. But much remains to be done before it completely disappears and the rights of these groups of the society are fully respected. Now days a number of PLWHA associations are being established throughout the country and are getting involved in the national efforts of fighting against HIV/AIDS. While these associations are involved in the design and implementation of various programs targeting people infected and affected by the virus their emergence and subsequent mushrooming is giving more voice to the debates surrounding the pandemic and to influence policy and the strategies of the government. Nevertheless, the effectiveness and meaningful contribution of these associations was compromised due to the uncoordinated, inconsistent and sometimes contradictory engagements and initiatives. aware of the situations and the need for coordinated and increased involvement of these associations a total of 25 PLWHA associations (embracing more than 2000 PLWHA members) found in the region have established their network /umbrella office in Awassa, capital of the Region in September 2006 while the number is reached to 71. The Network has legally registered as a nongovernmental organization and has got its license from the SNNPR Bureau of Justice. -

ISSN -2347-856X Refereed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 5.471 E- ISSN -2347-856X Refereed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653 ASSESSMENTOF VALUE ADDED TAX(VAT) AUDIT PRACTICE INCASE OF DURAME TOWN, ETHIOPIA Mr.Ermias Ersedo * Dr.V.Balamurugan** Dr.T.Hymavathi Kumari*** * Lecturer, Dept of Accounting and Finance, Dilla University, Ethiopia. ** Assistant Professor, Dept of Accounting and Finance, Dilla University, Ethiopia. *** Associate Professor, Dept of Accounting and Finance, Dilla University. Abstract This paper focuses on assessing Valueaddedtax (VAT) audit practice of Durame Town administration Revenue Authority, Ethiopia.Mixed research approach and descriptive survey was employed.The studyemployed both primary and secondary data.Questionnaire and interview were used to collectdata.This research was a survey involving VAT registrant tax payers who are served in Durame town tax authority.The data collected from 74 survey respondents were VAT registrants in the town revenue office and five (5)tax auditors who work in the tax authority and there maining one tax officials were interviewed.Most tax payers’view the Ethiopian tax lawisvague and opento interpretation in different ways for the same case. And low level of tax payers’knowledge and skill to keep proper books of accounts and financial reports.Most taxpayers’attitude towards VAT auditis not supportive and majority of there spondents couldn’t understandessence of VAT audit.The tax authority audit case selection method doesn’t incollecting data necessary in conducting VAT audit and there is lack of -

Ermias Bonkola

St. MARY’S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE FACULTY OF BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT OF TRENDS OF HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT: THE CASE OF MISHA WOREDA, HADIYA ZONE, SNNPR, ETHIOPIA BY ERMIAS BONKOLA A SENIOR ESSAY PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN MANAGEMENT MARCH 2013 SMUC St. MARY’S UNIVERSITY COLLEG FACULTY OF BUSINESS DEPARTEMENT OF MANAGEMENT This is to certify that the senor essay prepared by Ermias Bonkola: in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Management complies with the regulations of the University college and meets the accepted standards with respect to quality. APPROVED BY THE COMMITTEE OF EXAMINERS Chair person Signature Advisor Signature Internal Examiner Signature External Examiner Signature Acknowledgement Above all, I thank Almighty God for always with me in all my endeavors and giving me endurance to complete my study. I am very glad to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my advisor Tamirat Sulamo (M.A) for his invaluable guidance and constructive professional advises throughout my research. Especial thanks also to my family who were always by my side and who offered me financial, the material and moral support to complete this research work as well as may study. Moreover, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my best friend and staff members for their technical assistance and moral support in the due courses my research works and studies. Finally, I also grateful to surveyed government works and werada civil service department and data enumerators area are duly acknowledged for providing their willingness and valuable supports/cooperation. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

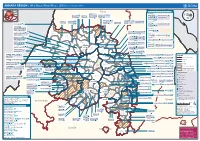

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Transhumance Cattle Production System in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is It Sustainable?

WP14_Cover.pdf 2/12/2009 2:21:51 PM www.ipms-ethiopia.org Working Paper No. 14 Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? Azage Tegegne,* Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia * Corresponding author: [email protected] Authors’ affiliations Azage Tegegne, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tesfaye Mengistie, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Tesfaye Desalew, Kutaber woreda Office of Agriculture and Rural Development, Kutaber, South Wello Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Worku Teka, Research and Development Officer, Metema, Amhara Region, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Eshete Dejen, Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), P.O. Box 527, Bahir Dar, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Correct citation: Azage Tegegne, Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen. 2009. Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project. -

Pdf | 170.55 Kb

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination of Bureau de Coordination des Humanitarian Affairs in Ethiopia Affaires Humanitaires au Ethiopie Website: Website: http://ochaonline.un.org/ethiopia http://ochaonline.un.org/ethiopia SITUATION REPORT: DROUGHT/FOOD CRISIS IN ETHIOPIA – 11th July 2008 Highlights: • MoH to start training for Health Extension Workers to support nutrition response • WFP faces a shortfall of 200,543 MT of food for emergency relief beneficiaries • Both the emergency relief food and PSNP pipelines have broken • Food insecurity likely to further exacerbate due to late planting of crops and continually soaring prices of food • High numbers of malnutrition cases reported in Borena, Bale, East and West Harerge zones of Oromiya and Gurage, Siltie, Kembata Tembaro, Sidama and Hadiya zones of SNNP Regions. Situation Update Soaring food prices and poor rain performance are expected to further affect the food security situation of the urban and rural poor, vulnerable pastoral and agropastoral populations according to WFP. Maize, harricot beans and teff planted using the late belg rains in April and May are performing well in some areas but are wilting in others due to dry spells, whilst in some areas crops have been destroyed by armyworm. Green harvest of maize and some Irish potato harvest is expected beginning in late August/September. WFP noted also that unusual stress associated with the migration of both cattle and people within the Somali Region and some areas of Afar and Oromiya Regions is resulting in increased clan conflict over resources. According to CARE, improved water availability has been recorded in South Gonder and East Harerge zones of Amhara and Oromiya Regions allowing cultivation of late planted crops. -

Social and Environmental Risk Factors for Trachoma: a Mixed Methods Approach in the Kembata Zone of Southern Ethiopia

Social and Environmental Risk Factors for Trachoma: A Mixed Methods Approach in the Kembata Zone of Southern Ethiopia by Candace Vinke B.Sc., University of Calgary, 2005 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography Candace Vinke, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Social and Environmental Risk Factors for Trachoma: A Mixed Methods Approach in the Kembata Zone of Southern Ethiopia by Candace Vinke Bachelor of Science, University of Calgary, 2005 Supervisory Committee Dr. Stephen Lonergan, Supervisor (Department of Geography) Dr. Denise Cloutier-Fisher, Departmental Member (Department of Geography) Dr. Eric Roth, Outside Member (Department of Anthropology) iii Dr. Stephen Lonergan, Supervisor (Department of Geography) Dr. Denise Cloutier-Fisher, Departmental Member (Department of Geography) Dr. Eric Roth, Outside Member (Department of Anthropology) Abstract Trachoma is a major public health concern throughout Ethiopia and other parts of the developing world. Control efforts have largely focused on the antibiotic treatment (A) and surgery (S) components of the World Health Organizations (WHO) SAFE strategy. Although S and A efforts have had a positive impact, this approach may not be sustainable. Consequently, this study focuses on the latter two primary prevention components; facial cleanliness (F) and environmental improvement (E). A geographical approach is employed to gain a better understanding of how culture, economics, environment and behaviour are interacting to determine disease risk in the Kembata Zone of Southern Ethiopia. -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE -

Soil Micronutrients Status Assessment, Mapping and Spatial Distribution of Damboya, Kedida Gamela and Kecha Bira Districts, Kambata Tambaro Zone, Southern Ethiopia

Vol. 11(44), pp. 4504-4516, 3 November, 2016 DOI: 10.5897/AJAR2016.11494 Article Number: C2000C461481 African Journal of Agricultural ISSN 1991-637X Copyright ©2016 Research Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR Full Length Research Paper Soil micronutrients status assessment, mapping and spatial distribution of Damboya, Kedida Gamela and Kecha Bira Districts, Kambata Tambaro zone, Southern Ethiopia Alemu Lelago Bulta1*, Tekalign Mamo Assefa2, Wassie Haile Woldeyohannes1 and Hailu Shiferaw Desta3 1School of Plant and Horticulture Science, Hawassa University, Ethiopia. 2Ethiopia Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA), Ethiopia. 3International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Received 29 July, 2016; Accepted 25 August, 2016 Micronutrients are important for crop growth, production and their deficiency and toxicity affect crop yield. However, the up dated information about their status and spatial distribution in Ethiopian soils is scarce. Therefore, fertilizer recommendation for crops in the country has until recently focused on nitrogen and phosphorus macronutrients only. But many studies have revealed the deficiency of some micronutrients in soils of different parts of Ethiopia. To narrow this gap, this study was conducted in Kedida Gamela, Kecha Bira and Damboya districts of Kambata Tambaro (KT) Zone, Southern Ethiopia, through assessing and mapping the status and spatial distribution of micronutrients. The micronutrients were extracted by using Mehlich-III multi-nutrient extraction method and their concentrations were measured by using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES). The fertility maps and predication were prepared by co-Kriging method using Arc map 10.0 tools and the status of Melich-III extractable iron (Fe), Zinc (Zn), boron (B), copper (Cu) and molybdenum (Mo) were indicated on the map. -

F-3: Livelihood Improvement Component

F-3: Livelihood Improvement Component F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Project Appendix F: Verification Projects F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Projects Table of Contents Page Agricultral Promotion Component ....................................................................................................... F-4-1 Natural Resource Management Component ........................................................................................ F-4-23 Livelihood Improvement Component .................................................................................................. F-4-31 F-4-i Appendix F: Verification Projects F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Projects Activity Sheet for JALIMPS Verification Project Agricultural Promotion Component 1: 1. Activity Demonstration/Verification Plot: Primary Crops (15 activities in total) Name 2. Site Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Kobo, Mekedela, Legambo, Aregoba - 2009 meher season: Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Mekedela, Kobo - 2009/10 belg season: Gidan, Mekedela, Legambo - 2010 meher season: Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Kobo 3. Objectives Demonstration/verification of integrated approaches for the improvement of productivity of primary crops & farm land conservation in the watershed. 4. Implementer CRGs under the guidance & supervision of DAs & WAO 5. Beneficiaries CRGs: 34 CRGs formed 34 CRGs x 5 members = 170 members (beneficiaries) 6. Activity Establishment of demonstration/verification plot(s) for the integrated approaches Description for the productivity improvement