Hell Remembers Quine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Decadence 1969-76 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") As usual, the "dark age" of the early 1970s, mainly characterized by a general re-alignment to the diktat of mainstream pop music, was breeding the symptoms of a new musical revolution. In 1971 Johnny Thunders formed the New York Dolls, a band of transvestites, and John Cale (of the Velvet Underground's fame) recorded Jonathan Richman's Modern Lovers, while Alice Cooper went on stage with his "horror shock" show. In London, Malcom McLaren opened a boutique that became a center for the non-conformist youth. The following year, 1972, was the year of David Bowie's glam-rock, but, more importantly, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell formed the Neon Boys, while Big Star coined power-pop. Finally, unbeknownst to the masses, in august 1974 a new band debuted at the CBGB's in New York: the Ramones. The future was brewing, no matter how flat and bland the present looked. Decadence-rock 1969-75 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Rock'n'roll had always had an element of decadence, amorality and obscenity. In the 1950s it caused its collapse and quasi-extinction. -

Press Release

LOOKING AT MUSIC: SIDE 2 EXPLORES THE CREATIVE EXCHANGE BETWEEN MUSICIANS AND ARTISTS IN NEW YORK CITY IN THE 1970s AND 1980s Photography, Music, Video, and Publications on Display, Including the Work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blondie, Richard Hell, Sonic Youth, and Patti Smith, Among Others Looking at Music: Side 2 June 10—November 30, 2009 The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, second floor Looking at Music: Side 2 Film Series September—November 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, June 5, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art presents Looking at Music: Side 2, a survey of over 120 photographs, music videos, drawings, audio recordings, publications, Super 8 films, and ephemera that look at New York City from the early 1970s to the early 1980s when the city became a haven for young renegade artists who often doubled as musicians and poets. Art and music cross-fertilized with a vengeance following a stripped-down, hard-edged, anti- establishment ethos, with some artists plastering city walls with self-designed posters or spray painted monikers, while others commandeered abandoned buildings, turning vacant garages into makeshift theaters for Super 8 film screenings and raucous performances. Many artists found the experimental music scene more vital and conducive to their contrarian ideas than the handful of contemporary art galleries in the city. Artists in turn formed bands, performed in clubs and non- profit art galleries, and self-published their own records and zines while using public access cable channels as a venue for media experiments and cultural debates. Looking at Music: Side 2 is organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, The Museum of Modern Art, and succeeds Looking at Music (2008), an examination of the interaction between artists and musicians of the 1960s and early 1970s. -

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

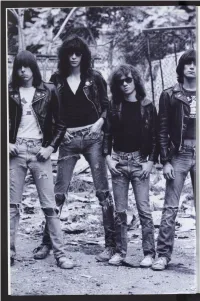

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. October 12, 2020 to Sun. October 18, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. October 12, 2020 to Sun. October 18, 2020 Monday October 12, 2020 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT The Day The Rock Star Died The Big Interview Michael Jackson - Michael Jackson was a singer, songwriter, dancer and known simply as “The The Band’s Robbie Robertson - Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson sits down with Dan Rather to talk about King of Pop.” His contributions to music, dance, and highly publicized personal life made him a his five decades as a progressive rock idol. global figure in popular culture for over four decades. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT Deep Purple’s: The Ritchie Blackmore Story A Year in Music From his pop roots with The Outlaws and his many session recordings in the sixties, through 1964 - Actor, writer, and musician, Tommy Chong dives into 1964: the year The Beatles took defining hard rock with Deep Purple and Rainbow in the seventies and eighties and on to the over, Motown Records became a driving force, and The Rolling Stones made their debut. Plus, a renaissance rock of Blackmore’s Night, Ritchie has proved that he is a master of the guitar across look at how political and social changes influenced pop music. a multitude of styles. This is the definitive story of a true guitar legend. 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT 10:20 AM ET / 7:20 AM PT The Big Interview Robert Plant And The Strange Sensation Edward Norton - Academy Award winner Edward Norton’s life is much more than Hollywood. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Raising pure hell a general theory of articulation, the syntax of structural overdetermination, and the sound of social movements Peterson II, Victor Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 RAISING PURE HELL a general theory of Articulation, the syntax of structural overdetermination, and the sound of social movements by Victor Peterson II dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College, London 2018 Acknowledgements Meaning is made, value taken. -

Building a Sustainable Natural Resource-Based Economy

Blaine House Conference on Maine’s Natural Resource-based Industry: Charting a New Course November 17, 2003 onference Report With recommendations to Governor John E. Baldacci Submitted by the Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer and Richard Davies, Co-chairs February 2004 . Acknowledgements The following organizations made the conference possible with their generous contributions: Conference Sponsors The Betterment Fund Finance Authority of Maine LL Bean, Inc. Maine Community Foundation US Fish and Wildlife Service US Forest Service This report was compiled and edited by: Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 (207) 287-3261 www.maine/gov/spo February 2004 Printed under Appropriation #014 07B 3340 2 . Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer, Co-chair, Richard Davies, Co-chair Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, Senior Policy Advisor, Governor Office USM Dann Lewis Spencer Apollonio Director, Office of Tourism, DECD Former Commissioner, Dept of Marine Resources Roland D. Martin Commissioner, Dept of Inland Fisheries and Edward Bradley Wildlife Maritime Attorney Patrick McGowan Elizabeth Butler Commissioner, Dept of Conservation Pierce Atwood Don Perkins Jack Cashman President, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Commissioner, Dept of Economic and Community Development Stewart Smith Professor, Sustainable Agriculture Policy, Charlie Colgan UMO Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, USM Robert Spear Commissioner, Dept of Agriculture Martha Freeman Director, State Planning Office -

06-Feb-21 SHOW NAME HOST NAME CRTC TIME START TIME

06-Feb-21 SHOW NAME HOST NAME CRTC TIME START TIME FINISH ARTIST/PSA SONG ALBUM Revolution Rock Dave Konstantino CODE & Adam Peltier 12 19:01 19:06 Talking The Kid With The Replaceable Head 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids (Destiny Street Remaster) Destiny Street Complete Staring In Her Eyes (Destiny Street 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Repaired) Destiny Street Complete 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Time (Destiny Street Remixed) Destiny Street Complete 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Don't Die (Single Version) Destiny Street Complete 12 19:20 19:25 Talking 12 19:25 19:44 Richard Hell Interview Part One 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Love Comes In Spurts Blank Generation 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids I'm Your Man Time 21 Richard Hell The Hunter Was Drowned Time 21 Dim Stars Baby Huey (Let's Dance) Dim Stars 12 19:55 20:00 Talking 21 20:02 20:25 Richard Hell Interview Part Two 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids You Gotta Lose Another World EP 21 Neon Boys That's All I Know (Right Now) Spurts: The Richard Hell Story 21 The Heartbreakers Hurt Me (Demo) Time 21 Television Blank Generation (Live) Spurts: The Richard Hell Story Funhunt: Live at CBGB's 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Ignore That Door (Live) & Max's 1978 and 1979 12 20:41 20:47 Talking Lowest Common Dominator (Destiny 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Street Remaster) Destiny Street Complete 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Going Going Gone (Demo) Destiny Street Complete 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Funhunt (Demo) Destiny Street Complete 12 20:55 20:57 Talking Destiny Street (Destiny Street 21 Richard Hell & The Voidoids Remixed) Destiny Street Complete *** If you do use this program please let me know that you are using it via email at [email protected] *** **This episode does not feature any Can Con. -

The History of Rock Music - the Eighties

The History of Rock Music - The Eighties The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Singer-songwriters of the 1980s (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Female folksingers 1985-88 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Once the effects of the new wave were fully absorbed, it became apparent that the world of singer-songwriters would never be the same again. A conceptual mood had taken over the scene, and that mood's predecessors were precisely the Bob Dylans, the Neil Youngs, the Leonard Cohens, the Tim Buckleys, the Joni Mitchells, who had not been the most popular stars of the 1970s. Instead, they became the reference point for a new generation of "auteurs". Women, in particular, regained the status of philosophical beings (and not only disco-divas or cute front singers) that they had enjoyed with the works of Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Suzy Gottlieb, better known as Phranc (1), was the (Los Angeles-based) songwriter who started the whole acoustic folk revival with her aptly-titled Folksinger (? 1984/? 1985 - nov 1985), whose protest themes and openly homosexual confessions earned her the nickname of "all-american jewish-lesbian folksinger". She embodied the historic meaning of that movement because she was a punkette (notably in Nervous Gender) before she became a folksinger, and because she continued to identify, more than anyone else, with her post- feminist and AIDS-stricken generation in elegies such as Take Off Your Swastika (1989) and Outta Here (1991). -

Robert Quine Page 1 of 1 6/14/2004

Page 1 of 1 Robert Quine (Filed: 14/06/2004) Robert Quine, who has died aged 61, was acknowledged to be one of the most original and formidably talented guitarists in rock music; a founder member of American punk band The Voidoids, he later worked with Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Lloyd Cole and Brian Eno. At first glance, Bob Quine appeared an unlikely punk. A nephew of the philosopher W V Quine, he was a tax lawyer until his mid-thirties, by which time he was already nearly bald. Even at the height of his success, he took to the stage in a well-ironed shirt and black sports jacket, his only concession to attitude being the wearing of sunglasses. Equally out of keeping with punk's ethos was his command of his instrument, from which he produced an intense, aggressive, dissonant sound. Lou Reed acclaimed him as "a magnificent guitar player . an innovative tyro of the vintage beast". His skills are best preserved on Blank Generation, the album he recorded with Richard Hell in 1977. Having renounced the law, he was then working in a Greenwich Village bookshop with Hell and Tom Verlaine, both members of the proto-punk group Television. Hell, having fallen out with Verlaine and later with Johnny Thunders of The Heartbreakers, which he had gone on to join, put together a new band with Quine, Ivan Julian and Marc Bell (later of The Ramones) - The Voidoids. Quine coaxed suitably angry sounds from his Stratocaster to frame Hell's nihilistic yet purposeful lyrics, and the LP - especially its title track - became an underground success. -

International Jazz News Festival Reviews Concert

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS TOP 10 ALBUMS - CADENCE CRITIC'S PICKS, 2019 TOP 10 CONCERTS - PHILADEPLHIA, 2019 FESTIVAL REVIEWS CONCERT REVIEWS CHARLIE BALLANTINE JAZZ STORIES ED SCHULLER INTERVIEWS FRED FRITH TED VINING PAUL JACKSON COLUMNS BOOK LOOK NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD Reviews OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 1 Jan Feb Mar Edition 2020 CADENCE Mainstream Extensions; Music from a Passionate Time; How’s the Horn Treating You?; Untying the Standard. Cadence CD’s are available through Cadence. JOEL PRESS His robust and burnished tone is as warm as the man....simply, one of the meanest tickets in town. “ — Katie Bull, The New York City Jazz Record, December 10, 2013 PREZERVATION Clockwise from left: Live at Small’s; JP Soprano Sax/Michael Kanan Piano; JP Quartet; Return to the Apple; First Set at Small‘s. Prezervation CD’s: Contact [email protected] WWW.JOELPRESS.COM Harbinger Records scores THREE OF THE TEN BEST in the Cadence Top Ten Critics’ Poll Albums of 2019! Let’s Go In Sissle and Blake Sing Shuffl e Along of 1950 to a Picture Show Shuffl e Along “This material that is nearly “A 32-page liner booklet GRAMMY AWARD WINNER 100 years old is excellent. If you with printed lyrics and have any interest in American wonderful photos are included. musical theater, get these discs Wonderfully done.” and settle down for an afternoon —Cadence of good listening and reading.”—Cadence More great jazz and vocal artists on Harbinger Records... Barbara Carroll, Eric Comstock, Spiros Exaras,