Elizabeth Kostina, Hairlines, Lamont Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Written Questions

4/21/2020 Test: MILADY CHAPTER 11 | Quizlet NAME 5 Written questions 1. abnormal hair loss. 2. hair flowing in the same direction, resulting from follicles sloping in the same direction. 3. an amino acid that joins together two peptide strands. 4. provides natural dark brown to black to the hair and is the dark pigment predominant in black and brunette hair. https://quizlet.com/302174566/test 1/5 4/21/2020 Test: MILADY CHAPTER 11 | Quizlet 5. the number of individual hair strands on 1 square inch (2.5 square centimeters) of scalp 5 Matching questions A. (lanugo hair) short, fine, unpigmented downy hair that 1. amino acids appears on the body, with the exception of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. 2. vellus hair 3. peptide bond 4. dermal papilla 5. hypertrichosis B. (end bond) chemical bond that joins amino acids to each other, end to end, to form a polypeptide chain. C. (hirsuties) condition of abnormal growth of hair, characterized by the growth of terminal hair in areas of the body that normally grow only vellus hair. D. units that are joined together end to end like pop beads by strong, chemical peptide bonds to form the polypeptide chains that comprise proteins. https://quizlet.com/302174566/test 2/5 4/21/2020 Test: MILADY CHAPTER 11 | Quizlet E. plural: dermal papilla. A small, cone-shaped elevation location located at the base of the root follicle that fits into the hair bulb. 5 Multiple choice questions 1. the bonds created when disulfide bonds are broken by hydroxide chemical hair relaxers after the relaxer is rinsed from the hair. -

Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis

Disclaimer: As a condition to the use of this document and the information contained herein, the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG) requests notification by e-mail before or contemporaneously to the introduction of this document, or any portion thereof, as a marked exhibit offered for or moved into evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or adjudicatory hearing or other proceeding (including discovery proceedings) in the United States or any foreign country. Such notification shall include: 1) the formal name of the proceeding, including docket number or similar identifier; 2) the name and location of the body conducting the hearing or proceeding; and 3) the name, mailing address (if available) and contact information of the party offering or moving the document into evidence. Subsequent to the use of this document in a formal proceeding, it is requested that FISWG be notified as to its use and the outcome of the proceeding. Notifications should be sent to: Redistribution Policy: FISWG grants permission for redistribution and use of all publicly posted documents created by FISWG, provided the following conditions are met: Redistributions of documents, or parts of documents, must retain the FISWG cover page containing the disclaimer. Neither the name of FISWG, nor the names of its contributors, may be used to endorse or promote products derived from its documents. Any reference or quote from a FISWG document must include the version number (or creation date) of the document and mention if the document is in a draft status. Version 2.0 2018.09.11 Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis 1. -

Beauty Trends 2015

Beauty Trends 2015 HAIR CARE EDITION (U.S.) The image The image cannot be cannot be displayed. displayed. Your Your computer computer may not have may not have enough enough memory to memory to Intro open the open the With every query typed into a search bar, we are given a glimpse into user considerations or intentions. By compiling top searches, we are able to render a strong representation of the United States’ population and gain insight into this specific population’s behavior. In our Google Beauty Trends report, we are excited to bring forth the power of big data into the hands of the marketers, product developers, stylists, trendsetters and tastemakers. The goal of this report is to share useful data for planning purposes accompanied by curated styles of what we believe can make for impactful trends. We are proud to share this iteration and look forward to hearing back from you. Flynn Matthews | Principal Industry Analyst, Beauty Olivier Zimmer | Trends Data Scientist Yarden Horwitz | Trends Brand Strategist Photo Credit: Blind Barber (Men’s Hair), Meladee Shea Gammelseter (Women’s Hair), Andrea Grabher/Christian Anwander (Colored Hair), Catface Hair (Box & Twist Braids), Maria Valentino/MCV photo (Goddess Braid) Proprietary + Confidential Methodology QUERY To compile a list of accurate trends within the Jan-13 Aug-13 Jan-14 Aug-14 Jan-15 Aug-15 beauty industry, we pulled top volume queries related to the beauty category and looked at their monthly volume from January 2013 to August 2015. We first removed any seasonal effect, and DE-SEASONALIZED QUERY then measured the year-over-year growth, velocity, and acceleration for each search query. -

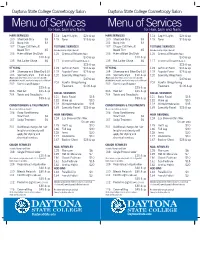

Menu of Services

Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Menu of Services Menu of Services for Hair, Skin and Nails for Hair, Skin and Nails HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) $10 & up $30 & up $10 & up $30 & up 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) _______________________________ $25 & up _______________________________ $25 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with $40 & up $40 & up detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) 203 Keratin Straightening 203 Keratin Straightening 202 Dominican -

Hairstyle Email Course TIP #1

Hairstyle Email Course TIP #1 Subject: Why you need to understand your hair type before changing your hairstyle ====================================================================== EMAIL Hi Tanner, Thank you for requesting the "7 Steps To Discovering Your Perfect Hairstyle" email course. These 7 short lessons will help you find the hairstyle that's perfect for you. A style that fits your unique face shape, personality and lifestyle. You will receive one email a day for 7 days. Each email will contain a link to the "lesson" (takes about 5 minutes to read). If you go through this course you'll walk away with a better understanding of how to select a style that brings out the best in you. So without further ado let's dive into Lesson #1: Understanding Your Hair Type. Click here to learn more. ============================================= LANDING PAGE The 4 Main Men's Hair Types One of the most important factors when it comes to choosing the hairstyle that's right for you has to do with your hair type. The density and texture of your hair will influence the "parameters" you have to work within when it comes to your new style. Below are the four main hair types along with tips for each. 1. Thick Hair Tips [Insert thick hair photo to the right] * If you have really thick hair, ask the stylist to thin it for you so it won't lay so thick at the bottom. * Choose a hairstyle that has a "layered cut" (true for both short & long hair). Otherwise it will lay as one big pile. * Comb or brush your hair to reduce the "poofiness". -

Wave Techniques

These ARE NOT your grandma’s perms and probably not the perms you learned in school! With quick, easy wraps, unique tools that create texture and modern styles, you can bring those wave profits back into your salon! Learn from the industry experts – Tressa! Before You Begin Analyze & Test Directions for IT Test: Analyze the hair and determine the Step 1 appropriate Tressa wave to use to reform Take a single strand of hair and hold the strand between thumb and forefinger of each hand, the hair (see the Wave Selection Chart about 11/ " apart. included in this kit). Read the important 2 cautions on the inside of the Tressa wave box before beginning service. Test with an IT Test (Internal Tension Test, below). Step 2 This step determines the minimum rod or Move your hands towards each other and the tool size needed to effectively produce hair will form a loop. The loop determines the the desired result and should never size of the tool to be used. be omitted. If the wrong size of tool is used for reforming, the longevity of the service may be compromised. General Waving Tips 1. Cleanse and prepare hair by using Remove-All Plus Shampoo. Lather and leave on the hair for 5 minutes. This ensures that all product build up and contaminates are removed from the hair. 2. Spray on Tressa’s Moistureze to balance the porosity and to ensure even, consistent curl patterns. 3. Apply Tressa’s Protage Skin Protector to all skin that will be exposed during the wave service. -

The Appeal of the Undercut Jasmine Schillinger Iowa State University

Fall 2014 Article 6 October 2014 The Appeal of the Undercut Jasmine Schillinger Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos Recommended Citation Schillinger, Jasmine (2014) "The Appeal of the Undercut," Ethos: Vol. 2015 , Article 6. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos/vol2015/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ethos by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BY JASMINE SCHILLINGER DESIGN NIKAYLA RATZ PHOTO KORRIE BYSTED The haircut that makes girls swoon ThTh ee Undercut.Undercut. ThTh at’sat’s thethe offioffi cialcial namename CainCain sharedshared hishis opinionopinion onon whywhy hehe thinksthinks justjust aa couplecouple ofof namesnames thatthat havehave sportedsported thesethese The Appeal of the forfor thisthis rapidlyrapidly growinggrowing hairstyle.hairstyle. WhenWhen thethe women enjoy this cut so much, “It’s just like stylish cuts. Macklemore, in particular, was sides of the head are shaved, with the back anything else that stands out, whether it be one of the fi rst to support the undercut style. slicked back, or messy styled top. Rocked by a nice body, good fashion sense or whatever Other names that have rocked the undercut at either a male or a female, it doesn’t matter. you’re into. I feel like women respect a man some point in time are Brad Pitt, Aaron Paul Undercuts are hot—period. thatthat isis well-groomedwell-groomed andand takestakes carecare ofof hishis and Cristiano Ronaldo. -

Makeup-Hairstyling-2019-V1-Ballot.Pdf

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Hairstyling For A Single-Camera Series A.P. Bio Melvin April 11, 2019 Synopsis Jack's war with his neighbor reaches a turning point when it threatens to ruin a date with Lynette. And when the school photographer ups his rate, Durbin takes school pictures into his own hands. Technical Description Lynette’s hair was flat-ironed straight and styled. Glenn’s hair was blow-dried and styled with pomade. Lyric’s wigs are flat-ironed straight or curled with a marcel iron; a Marie Antoinette wig was created using a ¾” marcel iron and white-color spray. Jean and Paula’s (Paula = set in pin curls) curls were created with a ¾” marcel iron and Redken Hot Sets. Aparna’s hair is blow-dried straight and ends flipped up with a metal round brush. Nancy Martinez, Department Head Hairstylist Kristine Tack, Key Hairstylist American Gods Donar The Great April 14, 2019 Synopsis Shadow and Mr. Wednesday seek out Dvalin to repair the Gungnir spear. But before the dwarf is able to etch the runes of war, he requires a powerful artifact in exchange. On the journey, Wednesday tells Shadow the story of Donar the Great, set in a 1930’s Burlesque Cabaret flashback. Technical Description Mr. Weds slicked for Cabaret and two 1930-40’s inspired styles. Mr. Nancy was finger-waved. Donar wore long and medium lace wigs and a short haircut for time cuts. Columbia wore a lace wig ironed and pin curled for movement. TechBoy wore short lace wig. Showgirls wore wigs and wig caps backstage audience men in feminine styles women in masculine styles. -

Chapter 18: Chemical Texture Services TOPICS

MILADY’S PROFESSIONAL BARBERING COURSE MANAGEMENT GUIDE LESSON PLAN 18.0 Chapter 18: Chemical Texture Services TOPICS 1. Introduction A. Overview B. Chemical Texture Services Defi ned 2. The Nature of Chemical Texture Services A. Chemistry B. Principle Actions 3. The Client Consultation A. Overview B. Scalp and Hair Analysis 4. Permanent Waving A. Overview B. The Perm Wrap C. Types of Permanent Waves D. Perm Selection E. Permanent Waving Wrapping Patterns F. Special Problems G. Safety Precautions H. Procedure 5. Reformation Curls A. Overview B. Products C. Procedure 6. Chemical Hair Relaxing A. Overview B. Types of Relaxers C. Safety Precautions D. Procedures NOTES TO THE INSTRUCTOR A study of permanent waving, reformation curls, and chemical hair relaxing provides barbering students with the ability to offer alternative services to their clients. For students in those states that require these services in the barbering curriculum, this chapter will provide the basics of chemical tex- ture services chemistry and application procedures. It is recommended that instructors review the simi- larities and differences of the products and procedures in some depth to facilitate and ensure students’ understanding of the information. STUDENT PREPARATION: Read Chapter 18: Chemical Texture Services STUDENT MATERIALS • Milady’s Standard Professional Barbering textbook • Milady’s Professional Barbering Student Workbook • Milady’s Professional Barbering Student CD-ROM • Writing materials • Mannequin and wet cape 403 © 2011 Milady, a part of Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use. -

Elegantbeauty Supplies| JOMARA WIGS & LACE WIGS SYNTHETIC RETAIL & WHOLESALE LARGEST BEAUTY SUPPLY in the COUNTRY

Valid Through 08/02/2021 @elegantbeauty_supplies| WWW.ELEGANTBEAUTYONLINE.COM JOMARA WIGS & LACE WIGS SYNTHETIC RETAIL & WHOLESALE LARGEST BEAUTY SUPPLY IN THE COUNTRY LOYALTY PROGRAM EARN POINTS ON EACH PURCHASE $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ LOYALTY PRICES 15 9 9 14 17 12 9 7 In All Our Sales To DALE LAVINIA EVE IDA SARAH SALLY VALENTINA ALMA Our Members TWO-IN-ONE • HALF WIGS • FULLCAP DRAWSTRING • SYNTHETIC BEAUTY SUPPLIES OPT-IN Superstores To receive Text Messages 14610 NE 18300 NW 3000 HALLANDALE 8373 10992 6840 6TH AVE. 2ND AVE. BEACH BLVD PINES BLVD. PEMBROKE RD. MIRAMAR PKWY NORTH MIAMI MIAMI GARDENS HALLANDALE PEMBROKE PINES MIRAMAR MIRAMAR SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC FL 33161 FL 33169 FL 33009 FL 33024 FL 33025 FL 33023 EGYPTIAN GIRL TEXAS GIRL BOSTON GIRL CALI GIRL NEW YORK GIRL NEVADA GIRL OAKLAND GIRL JAMAICAN GIRL t. 305.787.8540 t. 305.654.2828 t. 954.456.4666 t. 954.322.3220 t. 954.704.7875 t. 754.777.7440 $16 $16 $16 $16 $16 $16 $16 $16 BOSS LACE BOSS LACE BOSS LACE BOBBI BOSS BOBBI BOSS MODEL MODEL MODEL MODEL FREETRESS FREETRESS JOIN OUR LOYALTY SIGN UP TODAY LACE FRONT LACE FRONT LACE FRONT LACE FRONT 13”X4” LACE FRONT 13”X6” LACE IQUAL IQUAL PROGRAM TO GET & SAVE MONEY Swiss Lace Front Styled Braid THIS SALE Edger on Ponytail IL-003 Lace Frontal Natural Me HD Lace Front SAGA REMY BOSS BUNDLE 13x4 BRIO FULL WIG 4X4 CLOSURE LACE WIG 100% Remy Hair Wig 100% Natural Virigin 100% Natural Human Hair Human Hair 1, 1B 100% 100% NATURAL New New New New New New New HUMAN New New HUMAN HUMAN Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival Arrival HAIR HAIR HAIR SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC SYNTHETIC DANICE BOHEMIAN PAIGE VIVA WAN CHARLEE AFIA CARMELA 701 CHAYLYN ILLUSION MAY $29 $28 $79 $23 $49 $33 $65 $49 $38 $ 46 $ 39 $ 159 ALL GENIUS • SYNTHETIC LACE WIGS L-SHAPE / INVISIBLE PART SAGA REMY BOSS BUNDLE WIG BRIO FULL WIG NATURAL & LACE WIG NAT. -

Salon Pricing Cut Color Perm

SALON PRICING 513.793.0900 CUT COLOR PERM Master Salon Artistic Sr. Artistic DESIGN HAIRCUTS Designer Designer Director Director Director Design Consultation no charge no charge no charge no charge no charge Haircut Only 40.00 49.00 52.00 55.50 60.00 Haircut & Finished Design 45.50 55.50 60.00 66.00 72.00 Men’s Haircut 40.00 46.50 49.00 52.50 56.50 Children’s Haircut (12 and under) 27.50 32.00 34.00 37.50 39.50 Bang or Beard Trim 20.00 21.50 21.50 21.50 24.00 Haircut & Finished Design 33.50 43.50 47.50 53.00 60.00 with Color** DESIGN SERVICES Blowout/Airforming only 37.00 43.00 43.50 45.50 49.00 Blowout/Airforming with 27.00 31.50 32.50 34.50 37.00 Chemical Service** Design Set 44.00 50.00 60.00 60.00 62.50 Spiral Set 55.50 63.00 67.00 67.00 70.00 Wrap Set 46.00 52.00 55.50 55.50 59.00 Press & Curl 68.50 and up - Depending Upon Length Natural Curl Blowout (shoulder & above) 60.00 64.00 66.50 68.50 71.50 Natural Curl Blowout (long hair) 90.00 96.00 99.75 102.75 107.75 Extensions By Quotation - Prior Consultation Required Hair Extensions By Quotation - Prior Consultation Required Updo (Special Occasion Hair) 63.00 67.00 73.00 73.00 73.00 Natural Curl Updo 105.00 112.00 116.50 120.00 125.00 CONDITIONING TREATMENTS Conditioner 16.00 16.00 16.00 16.00 16.00 Scalp Renewal 37.00 37.00 37.00 37.00 37.00 Olaplex 30.00 30.00 30.00 30.00 30.00 *$15.00 charge when additional time required. -

Item Dispose Disinfect Disinfect How Illegal Storage

BUCKET OF FUN ITEM DISPOSE DISINFECT DISINFECT HOW ILLEGAL STORAGE HAIR FUNNEL CAPE COMB-OUT CAPE FOIL MAKE UP BRUSHES CLIPPER HEAD GRATER TOOTH BRUSH PAIR OF GLOVES COTTON SHEARS CUTICLE REMOVER 4 BUTTERFLY FILES 1 RAINBOW FILE TOE SEPARATORS PUMICE STONE NIPPERS Q-TIP BUTTERFLY CLAMP NAIL BRUSH ROLLER CLIP PERM ROD NAIL CLIPPERS MAKE UP WEDGE ROLLER CLIP ROLLER PICK BUCKET OF FUN ITEM DISPOSE DISINFECT DISINFECT HOW ILLEGAL STORAGE COLOR BRUSH PROCESSING CAP STYLE COMB NAIL BUFFER ORANGE WOOD STICK NAIL FILE CUSHION GRIP CLIPS - HAIR CLIPS VELCRO ROLLER GRIP HAIR ROLLER PAIR OF PEDI SLIPPERS PERM PAPERS CARDBOARD BOX OF RAZOR BLADES HAND SANITIZER 2 HAIR TIES 400 DOLLARS 2 COINS HAIR BRUSH TWEEZERS MASCARA WAND RUBBER BANDS WAX STRIP BUCKET OF FUN ANSWER KEY ITEM DISPOSE DISINFECT DISINFECT HOW ILLEGAL STORAGE HAIR FUNNEL CAPE X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL COMB-OUT CAPE X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL FOIL X MAKE UP BRUSHES X WASHED & DISINFECTED MAKEUP BRUSH CLIPPER HEAD X WASHED & DISINFECTED CLIPPER HEADS GRATER X TOOTH BRUSH X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL PAIR OF GLOVES X COTTON X SHEARS X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL METAL CUTICLE REMOVER X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL METAL 4 BUTTERFLY FILES x WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL 1 RAINBOW FILE X TOE SEPARATORS X PUMICE STONE X NIPPERS X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL METAL Q-TIP X BUTTERFLY CLAMP X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL NAIL BRUSH X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL ROLLER CLIP X WASHED & DISINFECTED GENERAL PERM ROD WASHED NAIL CLIPPERS X MAKE UP WEDGE X ROLLER CLIP X WASHED & DISINFECTED