The World Is Not a Foreign Land Curator: Quentin Sprague

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Page on Nyapanyapa

— OUR land people stories, 2017 — WE ARE BANGARRA We are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for our powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music and design. Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national currently in our 28th year. Our dance technique tour of a world premiere work, performed in is forged from over 40,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra, and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. Each an international tour to maintain our global has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait reputation for excellence. Islander background, from various locations across the country. Complementing this touring roster are education programs, workshops and special performances Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres and projects, planting the seeds for the next Strait Islander communities are the heart generation of performers and storytellers. of Bangarra, with our repertoire created on Country and stories gathered from respected Authentic storytelling, outstanding technique community Elders. and deeply moving performances are Bangarra’s unique signature. It’s this inherent connection to our land and people that makes us unique and enjoyed by audiences from remote Australian regional centres to New York. A MESSAGE from Artistic Director Stephen Page & Executive Director Philippe Magid Thank you for joining us for Bangarra’s We’re incredibly proud of our role as cultural international season of OUR land people stories. -

Djambawa Marawili

DJAMBAWA MARAWILI Date de naissance : 1953 Communauté artistique : Yirrkala Langue : Madarrpa Support : pigments naturels sur écorce, sculpture sur bois, gravure sur linoleum Nom de peau : Yirritja Thèmes : Yinapungapu, Yathikpa, Burrut'tji, Baru - crocodile, heron, fish, eagle, dugong Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual wellbeing of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales 2015 Year in Review

Art Gallery of New South Wales Art Wales South Gallery New of ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 2015 2015 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 2015 2 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2015 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2015 3 Our year in review 4 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2015 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2015 5 We dedicate this inaugural Art Gallery of New South Wales annual review publication to the Australian artists represented in the Gallery’s collection who have passed away during the year. 8 OUR VISION 9 FROM THE PRESIDENT Guido Belgiorno-Nettis 10 FROM THE DIRECTOR Michael Brand 12 YEAR AT A GLANCE 14 SYDNEY MODERN PROJECT 23 ART 42 IDEAS 50 AUDIENCE 60 PARTNERSHIPS 74 EXECUTIVE 75 CONTACTS 80 2016 PREVIEW Our vision From its base in Sydney, the Art Gallery of New South Wales is dedicated to serving the widest possible audience as a centre of excellence for the collection, preservation, documentation, interpretation and display of Australian and international art, and a forum for scholarship, art education and the exchange of ideas. Our goal is that by the time of our As Australia’s premier art museum, 150th anniversary in 2021, the Gallery we must reflect the continuing evolution will be recognised, both nationally of the visual arts in the 21st century and internationally, for the quality of alongside the development of new our collection, our facilities, our staff, channels of global communication that our scholarship and the innovative increasingly transcend national ways in which we engage with our boundaries. -

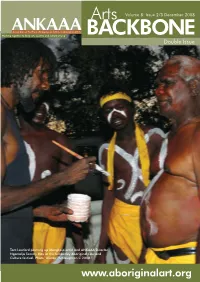

BACKBONE Double Issue

Arts Volume 8: Issue 2/3 December 2008 BACKBONE Double Issue Tom Lawford painting up Mangkaja artist and ANKAAA Director Ngarralja Tommy May at the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture festival. Photo: Alistair McNaughton C 2008. www.aboriginalart.org Welcome from the ANKAAA Chairman – Djambawa Marawili Darwin Office As Chairman of ANKAAA Director Donna Burak hosted this This year ANKAAA has GPO BOX 2152, DARWIN I need to see ANKAAA moving meeting at beautiful Garden Point, worked particularly NORTHERN TERRITORY, AUSTRALIA 0801 Melville Island, then experiencing the closely with the major Frogs Hollow Centre for the Arts into a future and we need to first signs of the coming wet season with funders: The Department 56 McMinn Street, Darwin, NT make a pathway for those people heavy bursts of afternoon rain. of the Environment, Ph +61 (0) 8 8981 6134 who are coming onto our board. Water, Heritage and Fax +61 (0) 8 8981 6048 The Katherine Regional Meeting the Arts (DEWHA), the Email [email protected] ANKAAA is a face for the art centres. was held at Springvale Homestead, Australia Council of It is really important in the eyes of Katherine, on 29 October with many the Arts and Arts NT www.ankaaa.org.au (as well as continuing government who look to ANKAAA to members travelling vast distances to www.aboriginalart.org attend and share news and discussion. to work with our other understand art centres and Aboriginal This idyllic retreat was also the venue for funders). Their practical All text and images are copyright the artist, artists from the Top End. -

Balnhdhurr - a Lasting Impression Yirrkala Print Space

BALNHDHURR - A LASTING IMPRESSION BALNHDHURR - A LASTING IMPRESSION YIRRKALA PRINT SPACE a lasting impression WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that this publication contains the names and images of deceased persons 2 3 4 5 CONTENTS Foreword 8 Introduction 10 Early Linocuts 14 Early Colour Reduction Linocuts 16 Early Collagraphs 18 Early Screenprints 22 Japanese Woodblocks 26 Etchings 30 Berndt Crayon Etchings 32 String Figure Prints 34 Ngarra – Young Ones Portraits 38 Gunybi Ganambarr Portraits 40 Seven Sisters 42 Djalkiri – We are Standing on Their Names 48 Mother / Daughter 50 Midawarr Suite 52 The Yuta Project 56 Gapan Gallery 60 Afterword 62 List of Works 66 Acknowledgements 68 6 7 THE SONG OF THE PRESS I arrived at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in May 1995 just as Andrew and Dianne Blake were bringing into fruition Steve Fox’s vision for a dedicated Print Space. The new studio was built onto the existing 1960’s handbuilt cypress pine ex- mission hospital building which had been the art centre since 1975. Since then I have been an interested observer. A nosy neighbor listening to the music coming over the fence. From within an art centre, which is a vehicle for serious lawmen and women to represent their law in natural media as a political and artistic act of resistance to the dominant settler culture, comes a completely different tune. A lilting, gentle, persistent, sweet melody of (mostly) women humbly working together to make beautiful things. It has been the sound of laughter and considerateness. The sound of compassion and empathy and respect and dignity. -

Annual Report 2010–11

ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Thapich Gloria Fletcher Dhaynagwidh (Thaynakwith) people The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the Eran 2010 cultural enrichment of all Australians through access aluminium to their national art gallery, the quality of the national 270 cm (diam) collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra programs, and the professionalism of Gallery staff. acquired through the Founding Donors 2010 Fund, 2010 Photograph: John Gollings The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, (back cover) corporate governance, administration and financial and Hans Heysen business management. Morning light 1913 oil on canvas In 2010–11, the National Gallery of Australia received 118.6 x 102 cm an appropriation from the Australian Government National Gallery of Australia, Canberra totalling $50.373 million (including an equity injection purchased with funds from the Ruth Robertson Bequest Fund, 2011 of $15.775 million for development of the national in memory of Edwin Clive and Leila Jeanne Robertson collection and $2 million for the Stage 1 South Entrance and Australian Indigenous Galleries project), raised $27.421 million, and employed 262 full‑time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2011 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

Unbranded Unbranded 06052019 — 22062019

unbranded unbranded 06052019 — 22062019 121 View St BENDIGO Victoria 3550 Damien Shen Dean Cross Gunybi Ganambarr Illiam Nargoodah James Tylor John Prince Siddon Ngarralja Tommy May Noŋgirrŋa Marawili Nyurpaya Kaika Burton Patrina Munuŋgurr Sharyn Egan Sonia Kurarra Wukun Wanambi Cover image: Sonia Kurarra, Martuwarra, 2015, syntheti c polymer paint on canvas, 152 x 137cm. Courtesy of the arti st and Mangkaja Arts. Image left : Gunybi Ganambarr at Gangan. Photo by Dave Wickens. Courtesy of the arti st and Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre. unbranded presents work by Indigenous contemporary unbranded as a curatorial enterprise questions these artists whose practices undermine and subvert the notion reductive and divisive modes of representation and of a singular Indigenous ‘brand’ or ‘aesthetic’. Their work interpretation, while simultaneously affirming the unpicks preconceptions of what Indigenous creative diversity, multiplicity and complexity of contemporary practice is or, should be, rejecting binary assumptions Indigenous experience, both live and inherited. around ‘traditional/non-traditional’, or ‘urban/remote’ practices and other applied, and often arbitrary Emerging from ongoing discussions around the premise categorisations. Their work instead reflects multiplicity, established by Glenn Iseger-Pilkington in his essay complexity and sometimes-conflicting experiences of Branded: the Indigenous Aestheticoriginally published by culture and identity in contemporary Australia. the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) in 2009, unbranded challenges the relevance of an The act of ‘branding’, clustering often disparate products ‘Indigenous brand’ or ‘aesthetic’, and refutes the notion together for marketing purposes, strips the voice of the that such a brand can somehow represent the experience individual artist or maker and separates creative output of Indigenous artists and Indigenous people across from the contemporary context in which it is created. -

Download PDF CV

BUKU-~ARR|GAY MULKA Yirrkala NT 0880 Phone 08 8987 1701 Fax 08 8987 2701 www.yirrkala.com [email protected] Djambawa Marawili Other Names Miniyawany Born 13/04/53 Died na Moiety Yirritja moiety Homeland Baniyala Clan Yithuwa Ma[arrpa - Nyu\u[upuy Ma[arrpa Selected Details of Artist’s Working Life Medium and Theme Earth Pigments on Bark Incised and painted wood scupture Printmaking Ceremonial objects - hollow log coffins Biography Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual well-being of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

The Wider Indigenous Community Benefits of Yirralka Rangers in Blue Mud Bay, Northeast Arnhem Land | Final Report

Rangers in place: the wider Indigenous community benefits of Yirralka Rangers in Blue Mud Bay, northeast Arnhem Land | Final report By Marcus Barber Report Title Author’s name Acknowledgements My sincere thanks go to the rangers and residents of Baniyala and GanGan in Northeast Arnhem Land, in particular Madarrpa clan elder and Baniyala community leader Djambawa Marawili. Thanks to staff at the Yirralka Rangers, The Mulka Project, and the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Arts Centre. This research was funded by the National Environmental Research Program, Northern Australia Hub supported by the Water for a Health Country and the Land & Water Flagships of the CSIRO. Thanks to Sue Jackson for her project leadership and considerable contribution to the literature review in Section 2 which is based on a forthcoming paper. Thanks also to fellow researchers on NERP 2.1 Indigenous livelihoods – Jon Altman, Sean Kerins, and Nic Gambold. Cathy Robinson, Sue Jackson, and David Preece provided important comments on the draft of this report. Film production would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of Ishmael Marika and Joseph Brady from the Mulka Project, editorial expertise from Vidhi Shah, and logistical support by David Preece and other staff from Yirralka Rangers. Front cover: Male rangers on sea patrol Back cover: Female Yirralka Rangers making soap at Baniyala ranger station Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation.