Re.Erences Is Appenaeo. Kluv NGRVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 CBS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 51 W. 52nd Street New York, NY 10019 (212) 975-4321 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant's principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 7.625% Senior Debentures due 2016 American Stock Exchange 7.25% Senior Notes due 2051 New York Stock Exchange 6.75% Senior Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes ☒ No o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

I Was Born in Arlington, Texas, Which Is Where I Lived Until I Was Twelve Years Old

I was born in Arlington, Texas, which is where I lived until I was twelve years old. My sister and I had a great childhood...climbing trees, riding bikes, and playing house and school! I attended Roquemore Elementary in Arlington ISD...grades K-6. My best friend and I were in the same 5th grade class. We were very excited to be in Mrs. Graham's class! My family moved to Mansfield when I was in 7th grade. I graduated from Mansfield High School when Mansfield had one high school, a plain old Wal-Mart, and only a Whataburger and Dairy Queen for fast food! Oh, how times have changed! I started attending college at what used to be called TCJC (Tarrant County Junior College). I earned an Associate of Arts in 1993. I then transferred to the University of Texas in Arlington. In 1995, I earned a Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies. Today, my husband, Patrick, and I still live in Mansfield. My husband works in Arlington as a Web Developer. We have two daughters... Ashley is a 2008 graduate of Kennedale High School. She graduated from Texas Wesleyan in 2012 with a degree in Business Marketing where she played basketball for four years. Go Lady Rams! She is currently a marketing representative for CBS radio, which includes stations like KLUV (98.7), KVIL (103.7), and The Ticket (97.1). Ashley got married to Ryan on October 17, 2015. We now have two grand-dogs! Amberlee is a 2014 graduate of KHS! She played volleyball and was a member of Key Club, FCA, PAL, and was crowned Homecoming Queen her senior year. -

Transfer of Control to Shareholders of Entercom Communciations Corp. BTC-20170320AAR WAXY 30837 SOUTH MIAMI FL AM ENTERCOM MIAMI LICENSE, LLC JOSEPH M

. P. NS CORP. NS CORP. APPENDIX 2109 Transfer of Control to Shareholders Entercom Communciations Corp. ENTERCOM DENVER II LICENSE, LLC JOSEPH M. FIELD SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. M ENTERCOM MIAMI LICENSE, LLCMMM CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC. JOSEPH M. FIELDM CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. MMM CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. -

Tapscan Custom Coverage

The Impact of Spot Loads and Spot Placement on Station Performance John Snyder Vice President, Customer Enhancements Arbitron Inc. ©2009 Arbitron Inc. Disclosures Any brand names, product names, titles used in this presentationare trademarks, trade names and/or copyrights of their respective holders. All images are used for purposes of demonstration only, and the entities associated with the products shown in those images are not affiliated with Arbitron in any way, nor have they provided endorsements of any kind. No permission is given to make use of any of the above, and suchuse may constitute an infringement of the holder’s rights. PPM ratings are based on audience estimates and are the opinion of Arbitron and should not be relied on for precise accuracy or precise representativeness of a demographic or radio market. ©2009 Arbitron Inc. 2 Critical Questions Regarding Spot Load and Placement »Do spot breaks really impact my audience levels? »Does it really matter where my spots are placed? »Does it really matter how many times a station breaks per hour? »Does it really matter how many Commercial minutes and/or units a station runs? Are six :30s the same as three :60s? ©2009 Arbitron Inc. 3 Do Spot Loads Really Impact Station Performance? ©2009 Arbitron Inc. 4 In PPM There Is a Relationship Between Audience and Content at the Quarter-Hour Level KIIS Los Angeles 18-49 AQH AQH Persons Audience % of non-music Persons % music per QH minutes 120,000 120 100,000 100 80,000 80 60,000 60 40,000 40 20,000 20 0 0 9AM_____________________________________________________________________________________5PM April 2009, Mon-Fri, 9AM-5PM ©2009 Arbitron Inc. -

CBS Radio Model Contest and Sweepstakes Rules

NTX Honda Fever Giveaway – Week 4 OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the NTX Honda Fever Giveaway – Week 4 promotion (the “Promotion”), which is being conducted by KJKK-FM, KMVK-FM, KVIL-FM, KLUV- FM, KRLD-AM, and KRLD-FM (the “Station”). The Promotion begins on July 14, 2014 and ends on July 21, 2014 (the “Promotion Dates”). b. To enter the Promotion, entrant may enter onsite beginning on July 14, 2014 at 9:00 am Central Time (“CT”) and ending on July 19, 2014 at 9:00 pm CT (the “Entry Period”) as follows: i. To enter onsite, visit the locations listed below starting on July 14, 2014 at 9:00 am CT and ending at 9:00 pm CT on July 19, 2014 to obtain an official entry form (available while supplies last), legibly hand write your first name and last name, complete address, city, state, zip code, telephone number (including area code), and date of birth on an official entry form and place the completed entry form in the dedicated collection box. P.O. Boxes are not permitted. All entries must be received by 9:00 pm CT on July 19, 2014. Entries submitted may not be acknowledged or returned. Failure to provide all required information may result in disqualification. AutoNation Honda Lewisville, 601 Waters Ridge, Lewisville, TX 75057; David McDavid Honda of Frisco, 1601 Dallas Parkway, Frisco, TX 75034; David McDavid Honda of Irving, 3700 W. -

In Re Applications of ALLIANCE BROADCASTING, L.P. And

FCC 95-511 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In re Applications of ) ALLIANCE BROADCASTING, L.P. ) FileNos. BAL/BALH-950922GG-GL and Subsidiaries ) BALFTB-950922GQ (Assignor/Transferor) ) and ) INFINITY BROADCASTING CORPORATION ) and Subsidiaries ) (Assignee/Transferee) ) For Assignment of the Licenses of KFRC(AM) and KYCY(FM) San Francisco, CA KYNG(FM), Dallas, TX KSNN(FM), Arlington, TX WYCD(FM), Detroit, MI KYCW(FM), Seattle, WA and License of FM Booster Station KYCY-FM1, San Francisco, CA And For Transfer of Control of the License of ) File Nos. BTC-950922GM KFRC-FM, San Francisco, CA ) BTCFTB-950922GN-GP And Licenses of FM Booster Stations KFRC-FM1, Danville, CA KFRC-FM2, Pleasonton, CA KFRC-FM3, Walnut Creek, CA MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: December 15, 1995 Released: January 16, 1996 By the Commission: Commissioner Barrett concurring and issuing a separate statement. 1 . The Commission has before it the above-captioned uncontested applications to assign the 5742 licenses and/or to transfer control of seven radio stations (six FM and one AM) and then- associated booster stations from subsidiaries of Alliance Broadcasting, L.P. ("Alliance") to subsidiaries of Infinity Broadcasting Corp. ("Infinity").1 Infinity currently controls 17 FM and 10 AM stations nationwide.2 If it acquires all of the assets and/or stock of Alliance as proposed, Infinity©s broadcast holdings would exceed our national ownership limits and, in two of the four markets involved (Dallas, Texas and San Francisco, California) would also exceed our local ownership limits. 2. To effectuate the proposed transactions, Infinity therefore requests temporary 12-month waivers of both our local and national radio broadcast ownership rules. -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Texas portal List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or programming formats. Call City of [3] Frequency [1][2] Licensee Format sign License KACU 89.7 FM Abilene Abilene Christian University Public Radio KAGT 90.5 FM Abilene Educational Media Foundation Contemporary Christian KAQD 91.3 FM Abilene American Family Association Southern Gospel KEAN- Townsquare Media Abilene 105.1 FM Abilene Country FM License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KEYJ-FM 107.9 FM Abilene Modern Rock License, LLC KGNZ 88.1 FM Abilene Christian Broadcasting Co., Inc. News, Christian KKHR 106.3 FM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. Tejano Townsquare Media Abilene KMWX 92.5 FM Abilene Adult Contemporary License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KSLI 1280 AM Abilene License, LLC Townsquare Media Abilene KULL 100.7 FM Abilene Classic Hits License, LLC Call City of [3] Frequency [1][2] Licensee Format sign License KVVO-LP 94.1 FM Abilene New Life Temple KWKC 1340 AM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. News/Talk Townsquare Media Abilene KYYW 1470 AM Abilene News/Talk License, LLC KZQQ 1560 AM Abilene Canfin Enterprises, Inc. Sports Talk KDLP-LP 104.7 FM Ace Ace Radio Inc. BPM RGV License Company, KJAV 104.9 FM Alamo Adult Hits L.P. KDRY 1100 AM Alamo Heights KDRY Radio, Inc. Christian Teaching & Preaching KQOS 91.7 FM Albany La Promesa Foundation KIFR 88.3 FM Alice Family Stations, Inc. -

On the Internet

aa39p11.qxp 10/16/08 2:01 PM Page 1 ADVERTISEMENT Advertising Age October 20, 2008 11 tion of radio“prime time”—morning and evening drive times—is changing. OUTL ETS “As a result of Internet radio, (TOP 5 MARKETS) there is a whole new daypart called HEARD IN NEW YORK ‘at work,’ ” Mr. Goodman says. “So CBSRADIO manyworkersaccessacomputerat WCBS-AM News their job during the day, and broad- WCBS-FM Classic hits band is fairly ubiquitous. We are WFAN-AM Sports ON THE INTERNET reaching consumers who might not WXRK-FM Active/alternative rock WITH A CLICK OF A MOUSE ON A CBS RADIO STATION WEB SITE OR WITH have listened to radio from 9 to 5.” For advertisers, that’s also great WINS-AM News NEW APPLICATIONS FOR MOBILE PHONES, CONSUMERS CAN LISTEN news. “Targeting people at work is WWFS-FM Adult contemporary TO THE LEADING ONLINE RADIO COMPANY WHEREVER THEY ARE great because they are engaged in ac- HEARD IN LOS ANGELES tive decision-making—looking at KCBS-FM Jack CBS Radio stations are heard by mil- Across America, online radio is products for the office but also goods KFWB-AM News lions of Americans every day—not growing rapidly; in a typical week, and services for leisure time,”he says. KLSX-FM FM talk just on home radios and in the car, more than 15 percent of adults 25 to “A lot of leisure activities are planned KNX-AM News but increasingly also on their com- 54 listened to online radio using while people are at work.” KROQ-FM Alternative rock puters and iPhones via streaming streaming technology, according to a In addition to online listening, KRTH-FM Classic hits technology. -

Vol. 1, No. 1, February 23, 2006 on January 3, 2006, CBS Corporation Began Formal Trad- Ing on the New York Stock Exchange Un

Vol. 1, No. 1, February 23, 2006 STRONG START FOR CBS CORPORATION A COMMITMENT TO INVESTORS “CBS Corporation is committed to operating all our On January 3, 2006, CBS assets with total distinction. We create world class Corporation began formal trad- popular content, and will continue to drive it to con- sumers across a wide range of platforms. Most ing on the New York Stock importantly, we will be paid for it. We seek to create Exchange under the NYSE ticker revenue and profit growth, and are committed to returning value to our shareholders. This means that symbols CBS and CBS.A. Since that time, CBS has we expect to pay attractive dividends and increase launched a number of initiatives to advance its core those dividends whenever we can.” strategy of creating world class content and maximizing -- CBS Corporation President and CEO Leslie Moonves revenue opportunities from that content. They include: Announcing the intent to form a new 5th network, The CW, with Warner Bros. Entertainment to debut in the fall of 2006 (see page 2). (Strong Start for CBS Corporation, continued) Announcing plans to divest its Paramount Parks Increasing the lineup of HD radio multicast program- division, a business which doesn’t fit with CBS’s core ming and expanding online access to CBS Radio (see strategy. The divestiture is expected to be completed in page 5). the second half of 2006. Signing CBS Outdoor contract renewals in NYC, Acquiring CSTV, a leading digital media company Atlanta and San Mateo County, CA (see page 5). devoted exclusively to college athletics (see page 3). -

For Public Inspection Comprehensive

REDACTED – FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT I. Introduction and Summary .............................................................................................. 3 II. Description of the Transaction ......................................................................................... 4 III. Public Interest Benefits of the Transaction ..................................................................... 6 IV. Pending Applications and Cut-Off Rules ........................................................................ 9 V. Parties to the Application ................................................................................................ 11 A. ForgeLight ..................................................................................................................... 11 B. Searchlight .................................................................................................................... 14 C. Televisa .......................................................................................................................... 18 VI. Transaction Documents ................................................................................................... 26 VII. National Television Ownership Compliance ................................................................. 28 VIII. Local Television Ownership Compliance ...................................................................... 29 A. Rule Compliant Markets ............................................................................................ -

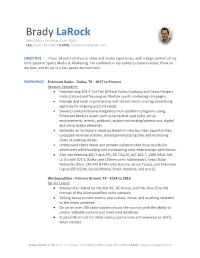

Brady Larock 4906 Zuma Ct • Dallas, TX • 75206 CELL (214) 726-2286 • E-MAIL [email protected]

Brady LaRock 4906 Zuma Ct • Dallas, TX • 75206 CELL (214) 726-2286 • E-MAIL [email protected] OBJECTIVE I have 14 years of diverse radio and media experience, with a large portion of my time spent in Sports Media & Marketing. I’m confident in my ability to communicate, think on my feet, and thrive in a fast paced environment. EXPERIENCE Entercom Radio - Dallas, TX - 2017 to Present Account Executive: Representing 105.3 The Fan (Official Dallas Cowboys and Texas Rangers radio station) and focusing on lifestyle sports marketing campaigns. Manage and work in partnership with direct clients and top advertising agencies for ongoing account needs. Develop comprehensive integrated multi-platform programs using Entercom Media's assets such as terrestrial spot radio, on-air endorsements, events, podcasts, custom contesting/promotions, digital and social media elements. Generate an increase in revenue based on new business opportunities, untapped revenue streams, developmental programs and increasing share of existing clients. Understand client needs and provide solutions that drive results for advertisers while building and maintaining solid relationships with clients. Also representing 100.3 Jack FM, 98.7 KLUV, ALT 103.7, 1080 KRLD-AM, La Grande 107.5, Radio.com (25mm users nationwide), Texas State Networks (Over 130 AM & FM radio stations across Texas), and Entercom Digital (SEO/SEM, Social, Mobile, Email, Website, and more). WestwoodOne - Farmers Branch, TX - 2014 to 2018 On-Air Talent: Weekend air talent for the Hot AC, AC Active, and Hits Now (Top 40) formats of the WestwoodOne radio network. Talking about current events, pop culture, music, and anything relatable to the demo audience.