Saurashtra University Library Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (Ii) the Dog of Tithwal

Black Ice Software LLC Demo version WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to PG English Semester IV! The basic objective of this course, that is, 415 is to familiarize the learners with literary achievements of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints you with modern movements in Indian thought to appreciate the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. You are advised to consult the books in the library for preparation of Internal Assessment Assignments and preparation for semester end examination. Wish you good luck and success! Prof. Anupama Vohra PG English Coordinator 1 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version 2 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version SYLLABUS M.A. ENGLISH Course Code : ENG 415 Duration of Examination : 3 Hrs Title : Indian Writing in English Total Marks : 100 Translation Theory Examination : 80 Interal Assessment : 20 Objective : The basic objective of this course is to familiarize the students with literary achievement of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints the students with modern movements in Indian thought to compare the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. UNIT - I Premchand Nirmala UNIT - II Saadat Hasan Manto, (i) Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (ii) The Dog of Tithwal (iii) The Price of Freedom UNIT III Amrita Pritam The Revenue Stamp: An Autobiography 3 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version UNIT IV Mohan Rakesh Half way House UNIT V Gulzar (i) Amaltas (ii) Distance (iii)Have You Seen The Soul (iv)Seasons (v) The Heart Seeks Mode of Examination The Paper will be divided into section A, B and C. -

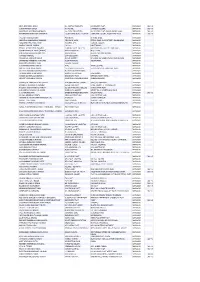

MINA MEHANDRA MARU C/O CHETAK PRODUCTS 64

MINA MEHANDRA MARU C/o CHETAK PRODUCTS 64, DIGVIJAY PLOT, JAMNAGAR 361005 SUDHA MAHESH SAVLA H.K.HOUSE, 9,KAMDAR COLONY, JAMNAGAR 361006 POPATBHAI DEVJIBHAI KANJHARIA C/o. TYAG INDUSTRIES, 58, DIGVIJAY PLOT, UDYOG NAGAR ROAD, JAMNAGAR 361005 BHIKHABHAI BHANUBHAI KANJHARIA C/O.KHODIAR BRASS PRODUCT 2,KRUSHNA COLONY, 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, JAMNAGAR 361005 VALLABH SAVJI SONAGRA PANAKHAN, IN VAKIL WADI, JAMNAGAR AMRUTLAL HANSRAJBHAI SONAGAR PIPARIA NI WADI, PETROL PUMP SLOPE STREET, GULABNAGAR JAMNAGAR JASODABEN FULCHAND SHAH PRADHNA APT., 1,OSWAL COLONY, JAMNAGAR RAKESH YASHPAL VADERA I-4/1280, RANJITNAGAR, JAMNAGAR BHARAT ODHAVJIBHAI BORANIA 1,SARDAR PATEL SOCIETY, OPP.MANGLAM, SARU SECTION ROAD, JAMNAGAR ISHANI DHIRAJLAL POPAT [MINOR] KALRAV HOSPITAL Nr.S.T.DEPO, JAMNAGAR SUSHILABEN LALJIBHAI SORATHIA BLOCK NO.1/4, G.I.D.C., Nr.HARIA SCHOOL, JAMNAGAR VIJYABEN AMBALAL LAXMI BUILDING K.V.ROAD, JAMNAGAR CHAMANLAL KESHAVJI NAKUM MAYUR SOCIETY, B/h.KRUSHNA NAGAR, PRAVIN DADHI WADI, JAMNAGAR JAMANBHAI MANJIBHAI CHANGANI 89,SHYAMNAGAR, INDIRA MARG, JAMNAGAR BHANUBEN MAGANLAL SHAH 4,OSWAL COLONY, JAMNAGAR ASHWIN HARIJIBHAI DHADIA A-64, JANTA SOCIETY, JAMNAGAR MULBAI DAYALJIBHAI MANGE C/o.KISHOR ENTERPRISE, 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, HANUMAN TEKRI, JAMNAGAR UTTAM BHAGWANJIBHAI DUDHAIYA MU.ALIA BADA MAIN ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAYSUKH NARSHIBHAI NAKUM RANDAL MATA STREET, JUNA NAGNA, JAMNAGAR HARESH ISHWARLAL BHOJWANI 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, OPP.ODHAVRAM HOTEL, JAMNAGAR HEMANT MADHABHAI MOLIYA JAYANTILAL CHANABHAI HOUS 5,KRUSHNANAGAR, JAMNAGAR CHANDULAL LIMBHABHAI BHESDADIA B-24,GOVERNMENT COLONY SARU-SECTION ROAD JAMNAGAR KANJIBHAI DEVSHIBHAI DEDANIA BEDESHVAR ROAD PATEL COLONY -5 "RANGOLI-PAN" JAMNAGAR KAUSHIK TRIBHOVANBHAI PANDYA BEHIND PANCHVATI COLLEGE AJANTA APARTMENT JAMNAGAR SUDHABEN JAYESHKUMAR AKBARI NANDANVAN SOCIETY STREET NO. -

Book Review of Gaban by Munshi Premchand in Hindi

Book Review Of Gaban By Munshi Premchand In Hindi Format:Kindle Edition/Verified Purchase. I liked the book immensely. The original book is in Hindi and I find that the translation is very good. Was this review. Book Format, Paperback. Categories: Hindi Books ( िहदी िकताब ). Tags: Hindi Books िहदी पुतक munshi prem chand Be the first to write a review of this product! Customers who bought Gaban / Prem Chand ( गबन Amazon.com: GABAN eBook: Munshi Premchand: Kindle Store. history, I was disappointed. Comment Was this review helpful to you? I read this book as a teenager and read it again now and liked it immensely again. Comment Was Bade Ghar ki Beti (बड़ े घर क बटे ी) (Hindi) (Hindi Edition) Kindle Edition. Munshi. Munshi Premchand is considered as one of the best Hindi authors and wrote numerous Hindi books, novels, stories and kahaniya. A novel writer, story writer and dramatist, he has been referred to as the "Upanyas Write a Review Rama soon finds himself committing fraud(Gaban) to buy her ornaments which leads. Like Godan and other contemporary novels, Gaban, too, is a charming piece of work by Munshi Premchand. It was first published in the year 1931, when India. Book review (written) 20 1. 2. Godaan - The Gift of a Cow is a Hindi novel by Munshi Premchand. (edit) Novels Gaban Bazaar-e-Husn or Seva Sadan. Book Review Of Gaban By Munshi Premchand In Hindi >>>CLICK HERE<<< कायाकप (Kayakalpa) has 61 ratings and 1 review:. Munshi Premchand To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

Acct Nm Address City Pin Code

ACCT NM ADDRESS CITY PIN CODE RAMESHCHANDRA BHAGVANJIBHAI RATHOD VIRANI MENSION,, 54, DIGVIJAY PLOT,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 MAHENDRA SHANTILAL MANIYAR RANJIT NAGAR,, BLOCK NO.G/8, ROOM NO.2097, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 PUNAMCHAND NEMCHAND SHAH 42/43,DIGVIJAY PLOT,, NEAR JAIN UPASHRAYA,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 ANANTRAI CHHABILDAS MAHTA ANDABAVA NO CHAKLOW,, BEHIND TALIKA SCHOOL, DHOBI'S DELI,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 VINODKUMAR KALYANJIBHAI VASANT [KILUBHAI] K V ROAD,, POTRY STREET,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR NAVINCHANDRA MULJI SHAH 14-SHNEHDHARA APPARTMENT, 6-PATEL COLONY, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR CHUNILAL TRIBHOVAN BUDH 55DIGVIJAY PLOT,, VIRPARBHAI'S HOUSE,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 HASMUKH HEMRAJ SHAH [HUF] 9,JAY CO-OP SOCIETY, AERODROME ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJESH RATILAL VISHROLIYA NEW ARAM COLONY,, NEAR JAY CORP., JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 BHARAT PARSHOTTAM VED GULAB BAUG,, ARYA SAMAAJ ROAD,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJIV MANILAL SHAH NEAR MORAR BAG,, OPP. LAL BAG, CHANDI BAZAAR,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 VINODCHANDRA JAGJIVAN SHAH JAYRAJ, OPP-GURUDATATRAY TEMPAL PALACE ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR MINA JAYESH MEHTA [STAFF] JAMNAGAR, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJENDRA BABULAL ZAVERI 504 SHALIBHADRA APTT, PANCHESWAR TOWER ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR JYOTIBEN JAGDISHKUMAR JOISAR 4 TH FLOOR,, MILAN APARTMENT, MIG COLONY,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 VIRENDRA OMPRAKASH ZAWAR 23/1/A RAJNAGAR, NR. ANMOL APPARTMENT, SARU SECTION ROAD JAMNAGAR 361006 MAHENDRA HEMRAJ SHAH (H.U.F) C/O VELJI SURA SHAH, 4 OSWAL COLONY SUMMAIR CLUB ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 MAHESH BHOVANBHAI DOBARIYA 'TARUN',, SARDAR PATEL NAGAR, B/H.JOLLY BUNGALOW,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR HIMATLAL LAKHAMSI SHAH C/O. R. C. LODAYA AND CO., PANCHESWAR TOWER ROAD,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 MUKTABEN GORDHANDAS KATARIA 8-A PARAS SOCIETY, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 AMRUTBEN TARACHAND SHAH 53, DIGVIJAY PLOT, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR DHANJI TAPUBHAI AJANI GEL KRUPA, OPP KOLI BUILDING, 3 KRUSHNANAGARKHODIYAR COLONY JAMNAGAR 361006 HITENDRA RAMNIKLAL HARKHANI 3,GOKULDHAM APPARTMENT,, K.P. -

SR.No Branch Name Address Pincode 1 Vasagade ICICI Bank Ltd.B.A.Landge Building G.P

SR.No Branch Name Address Pincode 1 Vasagade ICICI Bank Ltd.B.A.Landge Building G.P. No. 73Cs 254/1272 Ward No.1 Vasagade. 416416 2 Sherda ICICI Bank Ltd., & Post Sherda-335503 Teh. Bhadra Distt.Hanumangarh(Rajasthan) State:-Rajasthan 335503 3 Gudivada ICICI Bank Ltd., D No-11-218, Neniplaza, Eluru Road, Gudivada. 521301 4 Thiruvallur ICICI Bank Ltd., 4/120, Jawaharlal Nehru Road, Thiruvallur - 600201, Thiruvallur Dist., Tamilnadu. 600201 5 Sangamner ICICI Bank Ltd., Ashoka Heights, College Road, Sangamner-422605, Ahmednagar Dist., Maharashtra 422605 6 Palai ICICI Bank Ltd., Pendathanathu Plaza,Near Head Post Office,Palai-686575,Kerala 686575 7 Chalakudy ICICI Bank Ltd., R. Pullan, Ksrtc Road, Chalakudy- 680307, Dist Thrissur, Kerala Chalakudy - 680307 680307 8 Guntakal ICICI Bank Ltd., H No.16/130/8, Someshwara Complex, Opp., SLV Theater, Guntakal. 515801 ICICI Bank Ltd., Mauza Chak Jangi,tehsil-Nalagarh,Near Baddi Bus stand,Nalagarh Road,Baddi,Distt- 9 Baddi solan,HP-173205 173205 10 Baddi-Sai Road ICICI Bank Ltd., OPPOSITE KRISHNA COMPLEX, SAI ROAD' BADDI - 173205 State:-Himachal Pradesh 173205 11 Kharagpur ICICI Bank Ltd., 258/223/1, Malancha Road, Kharagpur - 721304, Paschim Medinipur Dist., West Bengal 721304 12 Varanasi-Sigra ICICI Bank Ltd., D-58/19-A4,Sigra 221010 13 Varanasi-Vishweshwarganj ICICI Bank Ltd., K 47/343 & K47/3, Ramagunj Katra, Viseshwargunj, Varanasi - 221001, Uttar Pradesh 221001 14 Varanasi-Nadesar ICICI Bank Ltd., S-17/26, Nadesar, Varanasi - 221002, Varanasi Dist., Uttar Pradesh 221002 15 Varanasi - Lanka ICICI Bank Ltd., 36\10, P.J.R., Shital Complex, Durgakund-Lanka road, Varanasi - 221005, Uttar Pradesh 221005 ICICI Bank Ltd., Ground floor and First floor, Building no. -

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR CODE ANDAMAN and NICOBAR ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair MB

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN AND MB 23, Middle Point, Mrs. Kavitha NICOBAR Port Blair - 744101, Ravi - 03192- ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Andaman PORT BLAIR ICIC0002144 232213/14/15 PARAMES WARA ICICI BANK LTD., RAO OPP. R. T. C. BUS KURAPATI- ANDHRA STAND, 98489 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD.504 001 ADILABAD ICIC0000617 37305- 4-3-168/1, TNGO’S ROAD (CINEMA ROAD ), PADAM HAMEEDPURA CHAND (DWARIKA NAGAR) GUPTA OPP. SRINIVASA 08732- NURSING HOME, 230230; ANDHRA ADILABAD 504001 934788180 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD (A.P>) ADILABAD ICIC0006648 1 ICICI Bank Ltd., Plot No. 91 & 92, Mr. Ramnathpuri Scheme, Satyendra ANDHRA JAIPUR,JHOTWA Jhotwara, Jaipur - Bhatt-141- PRADESH ADILABAD RA 302012, Rajasthan JAIPUR ICIC0006759 3256155 302229057 SUSHIL RAMBAGH PALACE KUMAR JAIPUR,RAM HOTEL RAMBAGH VYAS,0141- ANDHRA BAGH PALACE CIRCLE JAIPUR 3205604,,9 PRADESH ADILABAD HOTEL 302004 JAIPUR ICIC0006778 314661382 ICICI BANK LTD., NO. 12-661, GOKUL COMPLEX, BELLAMPALLY 08736 ROAD, MANCHERIAL, 255232, ANDHRA ADILABAD DIST. 504 MANCHERIY 08736 PRADESH ADILABAD MANCHERIYAL 208 AL ICIC0000618 255234 ICICI BANK LTD., OLD GRAM PANCHAYAT, MUDHOL - RAJESH 504102, TUNGA - ANDHRA ADILABAD DIST., +91 40- PRADESH ADILABAD MUDHOL ANDHRA PRADESH MUDHOL ICIC0002045 41084285 91 9908843335 504229502 ICICI BANK LIMITED PODDUTOOR COMPLEX, D.BO.1-2- 275, (OLD NO 1-2-22 TO 26 ) OPP . BUS SHERRY DEPOT, NIRMAL, JOHN 8942- NIRMAL ADILABAD (DIST), 224213 ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH – ,800847763 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504106 NIRMAL ICIC0001533 2 ICICI BANK LTD, NAVEED MR. SAI RESIDENCY, RAJIV GOPAL ROAD, PATRO ANDHRA ANANTAPUR- 515001 ANANTAPU (08554) - PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTPUR ANDHRA PRADESH R ICIC0000439 645033 ICICI BANK LTD., D.NO:12/114 TO 124, PRAMEEL R.S.ROAD, OPP DEVI A P -08559- NURSING HOME, 223943, ANDHRA DHARMAVARAM.515 DHARMAVA 970301725 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM 671 RAM ICIC0001034 4 16-337, GUTTI ROAD, GUNTAKAL-DIST. -

Elective English - Ii

ElectiveEnglish-II DENG105 ELECTIVE ENGLISH - II Copyright © 2013 Laxmi Publications All rights reserved Produced & Printed by LAXMI PUBLICATIONS (P) LTD. 113, Golden House, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara DLP-7804-068-ELECTIVE ENGLISH-I I C—6854/013/05 Typeset at: Excellent Graphics, Delhi Printed at: Giriraj Offset Press, Delhi. SYLLABUS Elective English - II Objectives: To develop analytical skills of students. To enhance writing skills of students. To improve understanding of literature among students. S. No. Topics 1. The Last Leaf by O. Henry 2. The Necklace by Guy de Maupassant 3. Martin Luther King's Letter from Birmingham Jail 4. My Vision for India by APJ Abdul Kalam 5. The Thought Fox by Ted Hughes 6. Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost 7. A Flight of Pigeons by Ruskin Bond 8. The Shroud by Munshi Prem Chand 9. The Right to Arms by Edward Abbey 10. Of Revenge by Francis Bacon 11. Indian Weavers by Sarojini Naidu 12. Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley CONTENTS Unit 1: The Last Leaf by O. Henry 1 Unit 2: The Necklace by Guy de Maupassant 15 Unit 3: Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail 33 Unit 4: My Vision for India by APJ Abdul Kalam 47 Unit 5: The Thought Fox by Ted Hughes 55 Unit 6: Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost 74 Unit 7: Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost—Detailed Study Analysis 81 Unit 8: A Flight of Pigeons by Ruskin Bond—Detailed Study 93 Unit 9: The Shroud by Munshi Premchand 105 Unit 10: The Right to Arms by Edward Abbey 122 Unit 11: Of Revenge by Francis Bacon 131 Unit 12: Indian Weavers by Sarojini Naidu 147 Unit 13: Ode to the West Wind by PB Shelly: Introduction 163 Unit 14: Ode to the West Wind by PB Shelly: Detailed Study 170 Unit 1: The Last Leaf by O. -

Download Internet, Mostly in the Developed Countries

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Development of Contemporary Media Subject: DEVELOPMENT OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA Credits: 4 SYLLABUS First Stirrings The Early Communication; Introduction to First Stirrings; Renaissance and Reformation; Rebirth of the Art; Culture; Literature and Media; the Great Revolutions. Mass Media Catalysts Rise of Democracy; Introduction to Media Catalysts; Path towards Convergence; Elements of Mass Media: Print Journalism; Print Media the American Scenario; Radio Journalism; Development of Films in the Early Ages; Contemporary Cinema; Television and its Impact on the Mass; Internet as a mass Medium; Convergence and Mass Media in the 21st Century; Mass communication in Ancient India. Mass Media in India The Modern Indian Media; the Indian Nationalistic Writings; Media in the Post-Colonial Era; Mass Media in Post Independent India; Radio and Television in India; Rise of Internet Journalism. The State and Media Role of Media and Media Responsibility; State and Media; Media Regulation and Censorship; Censor Ship and Right to Information. Suggested Readings: 1. The Media Student's Book; Gill Branston; Roy Stafford; Taylor & Francis. 2. Rethinking the Media Audience: the New Agenda; Pertti Alasuutari; Sage Publications. 3. Contemporary Media Issues; By William David Sloan; Wm. David Sloan; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 4. Mass Media in India; India Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Research and Reference Division. DEVELOPMENT OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA CONTENT Lesson No. Topic Page No. The First Stirrings Lesson 1 The Early Communication 1 Lesson 2 The First Stirrings 7 Lesson 3 Renaissance and reformation Rebirth of the Art Culture, Literature and 13 media Lesson 4 The Great Revolution 24 Mass Media Catalysts Lesson 5 The Rise of Democracy 33 Lesson 6 The Media Catalysts 39 Lesson 7 Media Catalysts Part –II 45 Lesson 8 Path Towards Convergence. -

DIVIDEND PAID on 15.04.2021 Name of the Investor

RAILTEL CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND INTERIM 2020-2021 AS ON 30/06/2021 DIVIDEND PAID ON 15.04.2021 Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF : 28.04.2028 Amount of Dividend Name of the Investor Address Pin Code (In Rs.) MR MANSUKH M DATTANI B/H KIRTI TEMPLE SONI VAD PORBANDAR PORBANDAR 360575 155.00 10-118, NAVRANG FLAT, BAPUNAGAR OPP BHIDBHANJAN MR DEV MEHTA HANUMAN TAMPALE, AHMEDABAD CITY AHMEDABAD 380024 155.00 B-1/64,ARJUN TOWER OPP.C.P.NAGAR PART-2 SAROJ JOSHI NR.SAUNDRYA APPT.GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 155.00 20, KRUSHNAKUNJ SOCIETY COLLEGE ROAD,TALOD MRS. SONALBEN B BHALAVAT SABARKANTHA 383215 155.00 61 CHITRODIPURA TA VISNAGAR DIST MEHSANA MEHSANA MISS RAMILABEN ISHWARBHAI CHAUDHARI MEHSANA 384001 155.00 C 38, ANANDVAN SOCIETY, NEW SAMA ROAD, NEAR NAVYUG PRAFULLA HARSUKHLAL SODHA ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VADODARA 390002 192.00 B-201 GOKULDHAM SOCIETY DEDIYASAN MAHESANA RAVI PRAKASH GUPTA MAHESANA MAHESANA 384001 155.00 A 44 HIM STATE DEWA ROAD SHAHEED BHAGAT SINGH MR MUAZZIZ SHARAF WARD AMRAI GAON LUCKNOW LUCKNOW 226028 155.00 MR PATEL NIRAVKUMAR SURESHBHAI 19 DAMODAR FALIYU VARADHARA TA VIRPUR KHEDA 388260 155.00 WARD NO 1, TAL .SHRIRAMPUR DIST. AHMEDNAGAR SARIKA AMOL MAHALE SHRIRAMPUR 413709 155.00 SATYA NARAYAN MANTRI 203, ANAND APPARTMENT, 9, BIJASAN COLONY INDORE 452001 15.00 ROSHNI AGARWAL P 887, BLOCK A, 2ND FLOOR LAKE TOWN KOLKATA 700089 310.00 VINOD KUMAR 11 RAJA ENCLAVE, ROAD NO. 44 PITAMPURA DELHI 110034 155.00 NAYAN MAHENDRABHAI BHOJAK S RAJAWADI CHAWL JAMBLI GALI BORIVALI WEST MUMBAI 400092 10.00 VETTOM HOUSE PANACHEPPALLY P O KOOVAPPALLY (VIA) TOM JOSE VETTOM KOTTAYAM DIST 686518 100.00 FLAT NO-108,ADHITYA TOWERS BALAJI COLONY TIRUPATI T.V.RAJA GOPALAN CHITTOOR(A.P) 517502 100.00 R K ESTET, VIMA NAGAR, RAIYA ROAD, NEAR DR. -

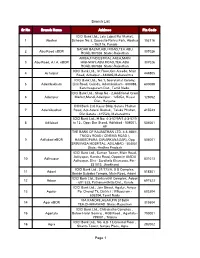

Branch List Page 1

Branch List Sr No Branch Name Address Pin Code ICICI Bank Ltd., Lala Lajpat Rai Market, 1 Abohar Scheem No.3, Opposite Nehru Park, Abohar 152116 - 152116, Punjab SADAR BAZAR,ABU ROAD,TEH.ABU 2 Abu Road eBOR 307026 ROAD,307026 State:-Rajasthan AMBAJI INDUSTRIAL AREA,MAIN 3 Abu Road, A.I.A. eBOR HIGHWAY,ABU ROAD,TEH.ABU 307026 ROAD,307026 State:-Rajasthan ICICI Bank Ltd., Ist Floor,Gm Arcade, Main 4 Achalpur 444805 Road, Achalpur - 444805,Maharashtra ICICI Bank Ltd., No.1, Secretariat Colony, 5 Adambakkam Link Road, Guindy, Adambakkam - 600088, 600088 Kancheepuram Dist., Tamil Nadu. ICICI Bank Ltd., Shop No - 2,Additional Grain 6 Adampur Market,Mandi,Adampur - 125052, Hissar 125052 Dist., Haryana ICICI Bank Ltd, Kasar Bldg, Satara Phaltan 7 Adarkibudruk Road, A/p Adarki Budruk, Taluka Phaltan, 415523 Dist Satara - 415523, Maharashtra ICICI Bank Ltd., H No: 4-3-57/9A/1,4-3-57/9 8 Adilabad to 12 , Opp: Bus Stand, Adilabad - 504001, 504001 AP THE BANK OF RAJASTHAN LTD. 4-3-168/1, TNGO's ROAD ( CINEMA ROAD ), 9 Adilabad eBOR HAMEEDPURA (DWARKANAGAR), Opp 504001 SRINIVASA HOSPITAL, ADILABAD - 504001 State:-Andhra Pradesh ICICI Bank Ltd., Suman Tower, Main Road, Adityapur, Kandra Road, Opposite AIADA 10 Adityapur 831013 Adityapur, Dist - Saraikela Kharsawa. Pin - 831013. Jharkhand ICICI Bank Ltd , 21/173/A, S S Complex, 11 Adoni 518301 Beside Saibaba Temple, Main Road, Adoni ICICI Bank Ltd., Sankarathil Complex, Adoor 12 Adoor 691523 - 691 523, Pathanamthitta Dist., Kerala ICICI Bank Ltd., Jain Street, Agalur, Aviyur 13 Agalur Po, Chengi Tk, District : Villupuram - 603204 603204, Tamil Nadu VIA KANORE,AGAR,PIN 313604 14 Agar eBOR 313604 TEH.DHARIAWAD State:-Rajasthan ICICI Bank Ltd., Chitrakatha Complex , 15 Agartala Below Hotel Somraj , HGB Road , Agartala - 799001 799001 , Tripura ICICI Bank Ltd., No. -

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Sum of Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) CIN/BCIN L72200TG1990PLC011146 Prefill Company/Bank Name NCC LIMITED 24-AUG-2017 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 867220.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) KIDARATHIL CHACKO BABY CHACKO P O BOX 5777 DOHA QATAR UNITED ARAB EMIRATESNA NA IN300239-IN300239-11881140Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1500.00 22-AUG-2018 AJITH KUMAR NA FAWAZ AL HOKAIR FASHION RETAIL PUNITED O BOX ARAB359 SHUMAISI EMIRATESNA RIYADH 11411 NA IN300239-IN300239-12655706Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend200.00 22-AUG-2018 J VASANTHAKUMAR NA 24 RAJESWARI NAGAR MAYILADUTHURAIINDIA TAMIL NADU TAMIL NADU MAYILADUTHURAI 609001 C12044700-12044700-04410951Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend4.00 22-AUG-2018 -

Library Collection Having Department As 'HINDI' Serialn Accessionn Classno Bookno Title Author Edition Year Publisher Price O O

Library Collection having Department as 'HINDI' SerialN AccessionN ClassNo BookNo Title Author Edition Year Publisher Price o o 1 0009364 891.431 GUP-M Panchavati by Gupta, 1 2002. Jhansi: 14.00 Maithilisharan Gupt Maithilisharan, Saket Prakashan, 2 0009385 891.431 GUP-M Panchavati by Gupt, 1 2002. Jhansi: 14.00 Maithilisharan Gupt Maithilisharan, Saket Prakashan, 3 0025116 491.438 AND-R Hindi lekhan by Andhariya 1st. 2019 Ahmedabad 250.00 Ravindra Andhariya Ravindra, Gurjar Prakashan 4 0025474 891.433 KAM Samudra mein khoya Kamleshwar, Allahabad: 125.00 0025475 891.433 KAM hua aadami by Lokbharati 0025476 891.433 KAM Kamaleshwar Prakashan. 0025477 891.433 KAM 0025478 891.433 KAM 0025479 891.433 KAM 0025480 891.433 KAM 0025481 891.433 KAM 0025482 891.433 KAM 0025483 891.433 KAM 0025484 891.433 KAM 0025485 891.433 KAM 0025486 891.433 KAM 0025487 891.433 KAM 0025488 891.433 KAM 0025489 891.433 KAM 0025490 891.433 KAM 0025491 891.433 KAM 0025492 891.433 KAM 0025493 891.433 KAM 0025494 891.433 KAM 0025495 891.433 KAM 0025496 891.433 KAM 0025497 891.433 KAM 0025498 891.433 KAM 5 891.433 Kathakalp ( Short Dayashankar, 2013 Ahmedabad 110.00 01 stories ) ed. by Parshva 891.433 Dayashankar Publication 01 891.433 01 Printed On : 25/02/2021 1 Library Collection having Department as 'HINDI' SerialN AccessionN ClassNo BookNo Title Author Edition Year Publisher Price o o 0025499 891.433 KAT 0025500 01 KAT 0025501 891.433 KAT 0025502 01 KAT 0025503 891.433 KAT 0025504 01 KAT 0025505 891.433 KAT 0025506 01 KAT 0025507 891.433 KAT 0025508 01 KAT 0025509