Current Status of Time Warner V. City of New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Amendment Implications of Convergence

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 9 Volume IX Number 2 Volume IX Book 2 Article 3 1999 Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence Andrew Jay Schwartzman Media Access Project Nicholas Jollymore Time Inc. Janine Jaquet New York University Jonathan Zittrain Berkman Center for Internet & Society; Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Jay Schwartzman, Nicholas Jollymore, Janine Jaquet, and Jonathan Zittrain, Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence, 9 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 421 (1999). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol9/iss2/3 This Transcript is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL I.TYP.DOC 9/29/2006 4:34 PM Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence Moderator: James Goodale* Panelists: Andrew Jay Schwartzman** Nicholas Jollymore*** Janine Jaquet**** Jonathan Zittrain***** MR. GOODALE: Well, I have to tell you—this is one of my more exciting moments, because I have taught a course on this very subject ever since I came to Fordham Law School. And no one could teach a more exciting course, because every year the technol- ogy changes, which means every year the law is subject to change. -

Mark Feldstein Witness Statement

UNITED STATES v. JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Declaration of Mark Feldstein I, Mark Feldstein, hereby declare as follows: 1. Expert witness background and role in this case I am a journalism historian and professor at the University of Maryland and serve as its Eaton Chair in broadcast journalism. I earned a bachelor’s degree from Harvard College in 1979 and a PhD from the University of North Carolina in 2002. In between, I worked for twenty years as an investigative reporter at CNN, NBC News, ABC News and local television stations in the US, broadcasting hundreds of reports that won several dozen journalism awards. I am the author of one book and numerous peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, and magazine and newspaper articles that have focused on various aspects of journalism history, investigative reporting, leaking and whistleblowing, freedom of the press, and related issues. I have been quoted hundreds of times as an expert on these and other journalism issues by the news media, including the Guardian, Observer, International Herald Tribune, BBC, Reuters, Agence France-Presse, New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Al Jazeera, and other outlets in the US, Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Mideast. I have lectured around the world on investigative reporting, censorship, freedom of the press, media history and journalistic ethics, and I have testified about these issues in the US Senate and in American courts in both criminal and civil cases. I have been asked by attorneys for Julian Assange to render my evaluation for this case from a journalistic perspective, focusing on the history of classified information disclosures to journalists and the US government’s response to such leaks; whether Assange is a journalist and entitled to protection of free speech/press under the US Constitution’s First Amendment; the journalistic implications of Assange’s indictment under the US Espionage Act; and the political dimensions of this case in the context of the Trump administration’s battle with the press. -

EXCERPTS: Media Coverage About Al Jazeera English

EXCERPTS: Media Coverage about Al Jazeera English www.aljazeera.net/english January, 2009 www.livestation.com/aje (free live streaming) The Financial Times: "Al-Jazeera becomes the face of the frontline" Associated Press: “Al Jazeera drew U.S. viewers on Web during Gaza War” The Economist: “The War and the Media” U.S. News & World Report/ Jordan Times: “One of Gaza War’s big winners: Al Jazeera” International Herald Tribune/New York Times: "AJE provides an inside look at Gaza`` The Guardian, U.K.: "Al Jazeera's crucial reporting role in Gaza" Arab Media and Society: “Gaza: Of Media Wars and Borderless Journalism” The Los Angeles Times: "GAZA STRIP: In praise of Al Jazeera" Kansas City Star: “A different take on Gaza” Columbia Journalism Review: "(Not) Getting Into Gaza" Le Monde, Paris: "Ayman Mohyeldin, War Correspondent in Gaza" Halifax Chronicle Herald, Canada: "Why can't Canadians watch Al Jazeera?" The Huffington Post: "Al Jazeera English Beats Israel's Ban with Exclusive Coverage" Haaretz, Israel: "My hero of the Gaza war" The National, Abu Dhabi: "The war that made Al Jazeera English ‘different’’ New America Media: “Al Jazeera Breaks the Israeli Media Blockade" Israeli Embassy, Ottawa: “How I learned to Love Al Jazeera” 1 The Financial Times Al-Jazeera becomes the face of the frontline …With Israel banning foreign journalists from entering Gaza, al-Jazeera, the Qatari state-owned channel, has laid claim to being the only international broadcast house inside the strip. It has a team working for its Arab language network, which made its name with its reporting from conflict zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Daniel Ellsberg

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY CENTRAL SECURITY SERVICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-6000 FOIA Case: 101038A 10 July 2017 JOHN GREENEWALD Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is our final response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of 6 March 2017 for Intellipedia entries on "PENTAGON PAPERS" and/ or "Daniel Ells berg" and/ or "Daniel Sheehan" as well as any search results pages. A copy of your request is enclosed. As stated in our initial response to you, dated 7 March 20 17, your request was assigned Case Number 101038. For purposes of this request and based on the information you provided in your letter, you are considered an "all other" requester. As such, you are allowed 2 hours of search and the duplication of 100 pages at no cost. There are no assessable fees for this request. Your request has been processed under the provisions of the FOIA. For your information, NSA provides a service of common concern for the Intelligence Community (IC) by serving as the executive agent for Intelink. As such, NSA provides technical services that enable users to access and share information with peers and stakeholders across the IC and DoD. -

War in Afghanistan (2001‒Present)

War in Afghanistan (2001–present) 1 War in Afghanistan (2001–present) The War in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001,[1] as the armed forces of the United States and the United Kingdom, and the Afghan United Front (Northern Alliance), launched Operation Enduring Freedom in response to the September 11 attacks on the United States, with the stated goal of dismantling the Al-Qaeda terrorist organization and ending its use of Afghanistan as a base. The United States also said that it would remove the Taliban regime from power and create a viable democratic state. The preludes to the war were the assassination of anti-Taliban leader Ahmad Shah Massoud on September 9, 2001, and the September 11 attacks on the United States, in which nearly 3000 civilians lost their lives in New York City, Washington D.C. and Pennsylvania, The United States identified members of al-Qaeda, an organization based in, operating out of and allied with the Taliban's Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, as the perpetrators of the attacks. In the first phase of Operation Enduring Freedom, ground forces of the Afghan United Front working with U.S. and British Special Forces and with massive U.S. air support, ousted the Taliban regime from power in Kabul and most of Afghanistan in a matter of weeks. Most of the senior Taliban leadership fled to neighboring Pakistan. The democratic Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was established and an interim government under Hamid Karzai was created which was also democratically elected by the Afghan people in the 2004 general elections. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council at the end of December 2001 to secure Kabul and the surrounding areas. -

General Photograph Collection

General Photograph Collection Title Description Slides Negs Color Prints A&E Networks X A.&.E. Network - X programming A.B.C. Video Enterprises, Inc. X A.B.C. Video Enterprises - X programming A.C.E. Awards X X X A.E.T.N. - programming X A.M. Cable X A.M.C. X A.M.C. - programming X A.M.P.E.X. Corporation X A.T.C. Pete Gatseos, Trygve X Myhren Ackerman, James X X Adams-Russell Company, Inc. X Adelphia Communications X Advertising Roundtable X Advertising Roundtable X Albert, Carl Test satellite transmission X X 1973 Allen, Edward X Allen, James X Allen, Paul G. X Alter, Robert H. X America’s Health Network X American Cablesystems X American Cablesystems - X programming Anixter Brothers, Inc. X Anstrom, Decker X X Arnold, William x X Arthur, Bea X Ash Le Donne X Astoria Hotel, Astoria Oregon X Athanas, Peter X X Atkins, Center Jr. X Audiocom X Augat X Babcock, Barry x X Back, George X Ban, Michael P. X Barco, George, J. X Barco, Yolanda G. X X Barnes, John L. X Bartley, Robert X Barton, Peter X Baruch, Ralph M. X Baum, Arthur X Baum, Stephen J. X Beales, Char X X Befera, Frank P. Range TV Cable, Hibbing, X MN Beisch, Chuck X Belden Corporation X Bell, David X Bell-Young, Shelah X Bennett, Edward X Berenhaus, Edward X Bernard, Bill X Bernovitz, Paul X Best, Alex X Bilodeau, Robert X Biondi, Frank J. Jr. X Bjornson, Edith C. X Bliss, Roy E. X Blonder-Tongue Laboratories X Borelli, Louis A. -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

'I Mn,Hurxicane" There's a Hurricane , Coming to Your Town!

NICKEL -BACK IN ACTION J . Nickelback's FORMAT FOCUS: Get-Dut-The-Vote Drives, On -site And Street Cove-age Return 'Gotta Pre Radio For Election 2CC8 Be Somebody' pp.16w 32, 46, 31, 54 Pounces On CHR /Top 40, Canadian P. o Is Live, Loca -And Reaping The Rewards Hot AC, Rock, Active Rock & Alternative After INTERACTIVE: Quin Fly :Est Offer First Airplay Week PLUS: New Multiplatform Radic Apps Brad Paisley's 'Side' Project RADIO & RECORDS PROFILE: Greater MeciE's He di Proves Instrumental Raphael OCTOBER 10 200E ND 1783 $6.50 www.FadioandRecordsan .aDVERTISEMEN- 'i_mn,Hurxicane" there's A Hurricane , Coming To Your town! Call NOW For An Interview With Sharmian. Time to Have Some Drive Time F -U -N!! 615-506-9198 Sharmian @gmail.com Nashville 615-506-9198 i myspace.com /Sharmian Reyna@trevi noenterpri ses. ne Contact L.A. 818 -660 -2888 Thanks Country Radìo..Keep on spinning "I Drank Myself To ßêd"! www.americanradiohistory.com America's nett smash. From America's favorite Idol. 04 ofe--/ rip II K iginal and savvy male finalist in the show's history." - NEW TIMES myspate.com/officialdavidcook Ilf RCA RECORDS IABEI IS AKINN Of SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INN(S) Q) RCGISTERED. poa. MARCAIS) REGISTRAOATS) RCA 1RADF:MARK MANACT 80 N1 SA. BMG LOGO IS A TRADEMARK OF BERTEISMANN MUSIC GROUP. INC. Qa 2008 RCA RI. CORDS, A UNIT Of SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAIN/8f NE www.americanradiohistory.com WWW.RADIOANDRECORDS.COM: INDUSTRY AND FORMAT NEWS, AS IT HAPPENS, AROUND THE CLOCK. RAR NewsFocs Pennington Promoted Legal Fireworks Continue Over ON THE WEl3 To WRIF PD Cell Phone -Only Sampling Accelerated For Diaries Greater Media/Detroit PPM Commercialization promotes active rock In a niove crafted to pre -empt any attempt to block the rollout of its embattled PPM rat- Responding to pressure by the Radio WRIF APD /MD Mark ings, Arbitron on Oct. -

The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-5-2018 News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Higgins-Dobney, Carey Lynne, "News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4410. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6307 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. News Work: The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting by Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Studies Dissertation Committee: Gerald Sussman, Chair Greg Schrock Priya Kapoor José Padín Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney News Work i Abstract By virtue of their broadcast licenses, local television stations in the United States are bound to serve in the public interest of their community audiences. As federal regulations of those stations loosen and fewer owners increase their holdings across the country, however, local community needs are subjugated by corporate fiduciary responsibilities. Business practices reveal rampant consolidation of ownership, newsroom job description convergence, skilled human labor replaced by computer automation, and economically-driven downsizings, all in the name of profit. -

USA V JULIAN ASSANGE EXTRADITION HEARING When

USA V JULIAN ASSANGE EXTRADITION HEARING When: Part 1: 24th February -28th February Part 2: 18th May - 5th June Where: Woolwich Crown Court/Belmarsh Magistrate's Court, which is adjacent to HMP Belmarsh (See end of this briefing for travel advice). Magistrate: Vanessa Baraitser Defence team: Solicitor Gareth Peirce (Birnberg, Peirce & Partners), lead Barristers Edward Fitzgerald QC, Doughty Street Chambers, Mark Summers QC, Matrix Chambers The US is seeking to imprison Julian Assange for obtaining and publishing the 2010/2011 leaks, which exposed the reality of the Bush Administration's "War on Terror": Collateral Murder (Rules of Engagement), Afghan War Diaries, Iraq War Logs, Cablegate, and The Guantanamo Files. The US began its criminal investigation against Julian Assange and WikiLeaks in early 2010. After several years, the Obama administration decided not to prosecute WikiLeaks because of the precedent that this would set against media organisations. In January 2017, the campaign to free Mr. Assange's alleged source Chelsea Manning was successful and President Obama gave her a presidential commutation and freed her from prison. In August 2017 an attempt was made under the Trump administration to pressure Mr. Assange into saying things that would be politically helpful to the President. After Mr. Assange did not comply, he was indicted by the Trump Administration and the extradition request was set in motion. Chelsea Manning was re-imprisoned due to her refusal to cooperate with the grand jury against WikiLeaks. President Trump has declared that the press is "the enemy of the people" (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/17/business/trump-calls-the-news-media-the-enemy-of-the- people.html). -

Who Watches the Watchmen? the Conflict Between National Security and Freedom of the Press

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

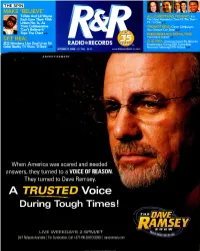

A TRUSTED Voice

THE SPIN MAKE 'BELIEVE' T Pain And LiI Wayne A MAS FORMAT: It's Each Earn Their Fifth The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year - Urban No. ls, As Til -'s Over Their Collaborative PROMOTIONS: Clever Campaigns 'Can't Believe It' You Station Can Steal Tops The Chart PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES: The Global Ir,pact GET ; THE PPM: Concerns Raised By Minority 302 Members Live Dual Lives On RADIO & RECORDS Broadcasters During R &R Conve -rtion Cable Reality TV Show 'Z Rock' Resonate Following PPM Rollout OCTOBER 17, 2008 NO. 1784 $6.EO www.RadioandRecc -c s.com ADVERTISEMENT When America was scared and needed nswers, they turned to a VOICE OF REASON. They turned to Dave Ramsey. A TRUSTED Voice During Tough Times! 7 /THEDAVÊ7 C AN'S HOW Ey LIVE WEEKDAYS 2-5PM/ET 0?e%% aáens caller aller cal\e 24/7 Re-eeds Ava lable For Syndication, Call 1- 877 -410 -DAVE (32g3) daveramsey.com www.americanradiohistory.com National media appearances When America was scared and needed focused on the economic crisis: answers, they turned to a voice Your World with Neil Cavuto (5x) of reason. They turned to Dave Ramsey. Fox Business' Happy Hour (3x) The O'Reilly Factor Fox Business with Dagen McDowell and Brian Sullivan Fox Business with Stuart Varney (5x) Fox Business' Bulls & Bears (2x) America's Nightly Scoreboard (2x) Larry King Live (3x) Fox & Friends (7x) Geraldo at Large (2x) Good Morning America (3x) Nightline The Early Show Huckabee The Morning Show with Mike and Juliet (3x) Money for Breakfast Glenn Beck Rick & Bubba (3x) The Phil Valentine Show and serving our local affiliates: WGST Atlanta - Randy Cook KTRH Houston - Michael Berry KEX Portland - The Morning Update with Paul Linnman WWTN Nashville - Ralph Bristol KTRH Houston - Morning News with Lana Hughes and J.P.