An Ecological Study of Mono Lake, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Long Valley Caldera, Mono-Inyo Craters

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-1933 US. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF LONG VALLEY CALDERA, MONO-INYO CRATERS VOLCANIC CHAIN, AND VICINITY, EASTERN CALIFORNIA By Roy A. Bailey GEOLOGIC SETTING VOLCANISM Long Valley caldera and the Mono-Inyo Craters Long Valley caldera volcanic chain compose a late Tertiary to Quaternary Volcanism in the Long Valley area (Bailey and others, volcanic complex on the west edge of the Basin and 1976; Bailey, 1982b) began about 3.6 Ma with Range Province at the base of the Sierra Nevada frontal widespread eruption of trachybasaltic-trachyandesitic fault escarpment. The caldera, an east-west-elongate, lavas on a moderately well dissected upland surface oval depression 17 by 32 km, is located just northwest (Huber, 1981).Erosional remnants of these mafic lavas of the northern end of the Owens Valley rift and forms are scattered over a 4,000-km2 area extending from the a reentrant or offset in the Sierran escarpment, Adobe Hills (5-10 km notheast of the map area), commonly referred to as the "Mammoth embayment.'? around the periphery of Long Valley caldera, and The Mono-Inyo Craters volcanic chain forms a north- southwestward into the High Sierra. Although these trending zone of volcanic vents extending 45 km from lavas never formed a continuous cover over this region, the west moat of the caldera to Mono Lake. The their wide distribution suggests an extensive mantle prevolcanic basement in the area is mainly Mesozoic source for these initial mafic eruptions. Between 3.0 granitic rock of the Sierra Nevada batholith and and 2.5 Ma quartz-latite domes and flows erupted near Paleozoic metasedimentary and Mesozoic metavolcanic the north and northwest rims of the present caldera, at rocks of the Mount Morrisen, Gull Lake, and Ritter and near Bald Mountain and on San Joaquin Ridge Range roof pendants (map A). -

Yosemite, Lake Tahoe & the Eastern Sierra

Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe PCC EXTENSION YOSEMITE, LAKE TAHOE & THE EASTERN SIERRA FEATURING THE ALABAMA HILLS - MAMMOTH LAKES - MONO LAKE - TIOGA PASS - TUOLUMNE MEADOWS - YOSEMITE VALLEY AUGUST 8-12, 2021 ~ 5 DAY TOUR TOUR HIGHLIGHTS w Travel the length of geologic-rich Highway 395 in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada with sightseeing to include the Alabama Hills, the June Lake Loop, and the Museum of Lone Pine Film History w Visit the Mono Lake Visitors Center and Alabama Hills Mono Lake enjoy an included picnic and time to admire the tufa towers on the shores of Mono Lake w Stay two nights in South Lake Tahoe in an upscale, all- suites hotel within walking distance of the casino hotels, with sightseeing to include a driving tour around the north side of Lake Tahoe and a narrated lunch cruise on Lake Tahoe to the spectacular Emerald Bay w Travel over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite Yosemite Valley Tuolumne Meadows National Park with sightseeing to include Tuolumne Meadows, Tenaya Lake, Olmstead ITINERARY Point and sights in the Yosemite Valley including El Capitan, Half Dome and Embark on a unique adventure to discover the majesty of the Sierra Nevada. Born of fire and ice, the Yosemite Village granite peaks, valleys and lakes of the High Sierra have been sculpted by glaciers, wind and weather into some of nature’s most glorious works. From the eroded rocks of the Alabama Hills, to the glacier-formed w Enjoy an overnight stay at a Yosemite-area June Lake Loop, to the incredible beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park, this tour features lodge with a private balcony overlooking the Mother Nature at her best. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

Insights Into Rhyolite Magma Dome Systems Based on Mineral and Whole Rock Compositions at the Mono Craters, Eastern California

ABSTRACT INSIGHTS INTO RHYOLITE MAGMA DOME SYSTEMS BASED ON MINERAL AND WHOLE ROCK COMPOSITIONS AT THE MONO CRATERS, EASTERN CALIFORNIA The Mono Craters magmatic system, found in a transtensional tectonic setting, consists of small magmatic bodies, dikes, and sills. New sampling of the Mono Craters reveals a wider range of magmatic compositions and a more complex storage and delivery system than heretofore recognized. Space compositional patterns, as well as crystallization temperatures and pressures taken from olivine-, feldspar-, orthopyroxene-, and clinopyroxene-liquid equilibria, are used to create a new model for the Mono Craters magmatic system. Felsic magmas erupted throughout the entire Mono Craters chain, whereas intermediate batches only erupted at Domes 10-12 and 14. Mafic magmas are spatially restricted, having erupted only at Domes 10, 12 and 14. Data from the new whole rock analyses illustrates a linear trend. Fractional crystallization does not replicate this trend but rather the linear trend indicates magma mixing. This study also analyzes samples from the Mono Lake Islands and the June Lake Basalts and compares them to the Mono Craters. Although the Mono Lake Islands fall into the intermediate to felsic group, they contain distinctly higher Al2O3 and Na2O at a given SiO2. Therefore, this study concludes that the Mono Craters represent a distinct magmatic system not directly related to the magmatic activity that created the Mono Lake Islands. Michelle Ranee Johnson May 2017 INSIGHTS INTO RHYOLITE MAGMA DOME SYSTEMS BASED -

A Diatom Proxy for Seasonality Over the Last Three Millennia at June Lake, Eastern Sierra Nevada (Ca)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences Earth and Environmental Sciences 2019 A DIATOM PROXY FOR SEASONALITY OVER THE LAST THREE MILLENNIA AT JUNE LAKE, EASTERN SIERRA NEVADA (CA) Laura Caitlin Streib University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.291 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Streib, Laura Caitlin, "A DIATOM PROXY FOR SEASONALITY OVER THE LAST THREE MILLENNIA AT JUNE LAKE, EASTERN SIERRA NEVADA (CA)" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ees_etds/70 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Environmental Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

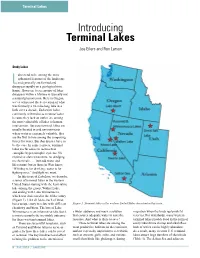

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Campground in Yosemite National Park

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Tioga Road/Big Oak Flat Road" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 End of Tioga Pass Road on Scenic Tioga Pass Road on State Highway #120, ends at the junction of State Highway #120 Big Oak Road just outside Yosemite Valley within Yosemite National Park, California. Altitude: 6158 feet 0.6 Tuolumne Grove Trail Tuolumne Grove Trail Head, Tioga Pass Road, Tuolumne Grove, is a Head sequoia grove located near Crane Flat in Yosemite National Park, California Altitude: 6188 feet 3.7 Old Big Oak Flat Road South to Tamarack Flat Campground in Yosemite National Park. Has 52 campsites, picnic tables, food lockers, fire rings, and vault toilets. Altitude: 7018 feet 6.2 Old Tioga Road Trail To Old Tioga Road, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, lies in Hetch Hetchy Valley, which is completely flooded by the Hetch Hetchy Dam, in Yosemite National Park, California. Wapama Falls, in Hetch Hetchy Valley, Lake Vernon, Rancheria Falls, Rancheria Creek, Camp Mather Lake. Altitude: 6772 feet 6.2 Trail to Tamarrack Flat Altitude: 6775 feet Campground 13.7 Siesta Lake Altitude: 7986 feet 14.5 White Wolf Road To White Wolf Campground, located outside of Yosemite Valley, just off Tioga Pass Road in California. Altitude: 8117 feet 16.5 Access To Luken's Lake, Yosemite Creek Trail, Altitude: 8182 feet 19.7 Access A mountainous Road/Trail, Quaking Aspen Falls, is a seasonal water fall, that stream relies on rain and snow melting, dries up in summer, located just off Tioga Pass Road, in Yosemite National Park, Altitude: 7500 feet 20.3 Quaking Aspen Falls East of highway. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

Chapter 3K. Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures - Cultural Resources

Chapter 3K. Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures - Cultural Resources This chapter addresses potential impacts of the alternatives on cultural resources in Mono Basin and Upper Owens River basin. Impacts are generally in the realm of potential disturbance to cultural resource sites from channel erosion, recreational activity, and restoration activities along the diverted streams and Owens River. Few effects would result from establishing higher or lower lake levels because no sites are expected to be present on the relicted lands. As described below, some diminishment in the use of the lake's food resources by Native Americans may have occurred during the diversion period, but choice of an alternative would little affect future resource utilization as long as resources of Native American importance are avoided during restoration activities. SOURCES OF INFORMATION Background Research A record search was conducted at the Eastern Information Center of the California Archaeological Inventory, University of California, Riverside, to determine the types and locations of known cultural resources within the areas of concern. Primary and secondary archeological, ethnographic, and historical sources were consulted for information pertaining to the areas of concern, including: # the National Register of Historic Places, # California Historical Landmarks, and # California Inventory of Historical Resources. Literature considered in this process is cited in the following discussions. Information on the Mono Lake Paiute is presented by Davis (1959, 1961, 1965, 1962, 1963, 1964), Curtis (1926), Kroeber (1925), and Merriam (1955, 1966:Part 1). Primary accounts of the Owens Valley Paiute are contained in Steward (1929, 1933, 1934, 1936, 1938a, 1938b). Additional information can be found in Davis (1961), Driver (1937), Kroeber (1925, 1939, 1959), and Merriam (1955). -

Regional Transportation Plan

MONO COUNTY REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN Mono County Local Transportation Commission Mono County Community Development Department Town of Mammoth Lakes Community Development Department MONO COUNTY LOCAL TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Fred Stump, Chair (Mono County) Shields Richardson, Vice-Chair (Mammoth Lakes) Jo Bacon (Mammoth Lakes) Tim Fesko (Mono County) Larry Johnston (Mono County) Sandy Hogan (Mammoth Lakes) STAFF Mono County Scott Burns, LTC Director Gerry Le Francois, Principal Planner Wendy Sugimura, Associate Analyst Jeff Walters, Public Works Director Garrett Higerd, Associate Engineer Courtney Weiche, Associate Planner C.D. Ritter, LTC Secretary Megan Mahaffey, Fiscal Analyst Town of Mammoth Lakes Haislip Hayes, Associate Civil Engineer Jamie Robertson, Assistant Engineer Caltrans District 9 Brent Green, District 9 Director Ryan Dermody, Deputy District 9 Director Planning, Modal Programs, and Local Assistance Denee Alcala, Transportation Planning Branch Supervisor Eastern Sierra Transit Authority (ESTA) John Helm, Executive Director Jill Batchelder, Program Coordinator TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 1 Transportation Directives .......................................................................................................................... 1 Summary of Needs and Issues .................................................................................................................. -

Wood Anatomy of Senecioneae (Compositae) Sherwin Carlquist Claremont Graduate School

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 3 1962 Wood Anatomy of Senecioneae (Compositae) Sherwin Carlquist Claremont Graduate School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Carlquist, Sherwin (1962) "Wood Anatomy of Senecioneae (Compositae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol5/iss2/3 ALISO VoL. 5, No.2, pp. 123-146 MARCH 30, 1962 WOOD ANATOMY OF SENECIONEAE (COMPOSITAE) SHERWIN CARLQUISTl Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California INTRODUCTION The tribe Senecioneae contains the largest genus of flowering plants, Senecio (between 1,000 and 2,000 species). Senecioneae also encompasses a number of other genera. Many species of Senecio, as well as species of certain other senecionean genera, are woody, despite the abundance of herbaceous Senecioneae in the North Temperate Zone. Among woody species of Senecioneae, a wide variety of growth forms is represented. Most notable are the peculiar rosette trees of alpine Africa, the subgenus Dendrosenecio of Senecio. These are represented in the present study of S. aberdaricus (dubiously separable from S. battescombei according to Hedberg, 195 7), S. adnivalis, S. cottonii, and S. johnstonii. The Dendra senecios have been discussed with respect to taxonomy and distribution by Hauman ( 1935) and Hedberg ( 195 7). Cotton ( 1944) has considered the relationship between ecology and growth form of the Dendrosenecios, and anatomical data have been furnished by Hare ( 1940) and Hauman ( 19 3 5), but these authors furnish little information on wood anatomy.