Open PDF 387KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4258, 19 June 2015 By Cheryl Pilbeam The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Historical background 3. The Wilson doctrine 4. Prison surveillance 5. Damian Green 6. The NSA files and metadata 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 4258, 19 June 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Historical background 4 3. The Wilson doctrine 5 3.1 Criticism of the Wilson doctrine 6 4. Prison surveillance 9 4.1 Alleged events at Woodhill prison 9 4.2 Recording of prisoner’s telephone calls – 2006-2012 10 5. Damian Green 12 6. The NSA files and metadata 13 6.1 Prism 13 6.2 Tempora and metadata 14 Legal challenges 14 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring 15 Cover page image copyright: Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The Wilson Doctrine Summary The convention that MPs’ communications should not be intercepted by police or security services is known as the ‘Wilson Doctrine’. It is named after the former Prime Minister Harold Wilson who established the rule in 1966. According to the Times on 18 November 1966, some MPs were concerned that the security services were tapping their telephones. In November 1966, in response to a number of parliamentary questions, Harold Wilson made a statement in the House of Commons saying that MPs phones would not be tapped. More recently, successive Interception of Communications Commissioners have recommended that the forty year convention which has banned the interception of MPs’ communications should be lifted, on the grounds that legislation governing interception has been introduced since 1966. -

The Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Education

House of Commons Education Committee The Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Education Oral Evidence Tuesday 24 April 2012 Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, Secretary of State for Education Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 April 2012 HC 1786-II Published on 26 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £5.50 Education Committee: Evidence Ev 29 Tuesday 24 April 2012 Members present: Mr Graham Stuart (Chair) Alex Cunningham Ian Mearns Damian Hinds Lisa Nandy Charlotte Leslie Craig Whittaker ________________ Examination of Witness Witness: Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, Secretary of State for Education, gave evidence. Q196 Chair: Good morning, Secretary of State. critical. If there is one unifying theme, and I suspect Thank you very much for joining us. Having been Sir Michael would agree, it is that the most effective caught short in our last lesson and now being late for form of school improvement is school to school, peer this one, there were suggestions of detention for to peer, professional to professional. We want to see further questioning, but we are delighted to have you serving head teachers and other school leaders playing with us. If I may, I will start just by asking you about a central role. what the Head of Ofsted told us when he recently gave evidence. He said, “It seems to me there needs Q198 Chair: On that basis, are you disappointed that to be some sort of intermediary layer that finds out so few of the converter academies—the outstanding what is happening on the ground and intervenes and very strong schools that have converted to before it is too late. -

Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness

All Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness Emergency COVID-19 measures – Officers Meeting Minutes 13 July 2020, 10-11.30am, Zoom Attendees: Apologies: Neil Coyle MP, APPG Co-Chair Jason McCartney MP Bob Blackman MP, APPG Co-Chair Steve McCabe MP Lord Shipley Julie Marson MP Ben Everitt MP Stephen Timms MP Sally-Ann Hart MP Rosie Duffield MP Baroness Healy of Primrose Hill Debbie Abrahams MP Lord Holmes of Richmond Andrew Selous MP Lord Young of Cookham Kevin Hollinrake MP Feryal Clark MP Nickie Aiken MP Richard Graham MP Parliamentary Assistants: Layla Moran MP Graeme Smith, Office of Neil Coyle MP Damian Hinds MP James Sweeney, Office of Matt Western MP Tommy Sheppard MP Gail Harris, Office of Shaun Bailey MP Peter Dowd MP Harriette Drew, Office of Barry Sheerman MP Steve Baker MP Tom Leach, Office of Kate Osborne MP Tonia Antoniazzi MP Hannah Cawley, Office of Paul Blomfield MP Freddie Evans, Office of Geraint Davies MP Greg Oxley, Office of Eddie Hughes MP Sarah Doyle, Office of Kim Johnson MP Secretariat: Panellists: Emily Batchelor, Secretariat to APPG Matt Downie, Crisis Other: Liz Davies, Garden Court Chambers Jasmine Basran, Crisis Adrian Berry, Garden Court Chambers Ruth Jacob, Crisis Hannah Gousy, Crisis Cllr Kieron William, Southwark Council Disha Bhatt, Crisis Cabinet Member for Housing Management Saskia Neibig, Crisis and Modernisation Hannah Slater, Crisis Neil Munslow, Newcastle City Council Robyn Casey, Policy and Public Affairs Alison Butler, Croydon Council Manager at St. Mungo’s Chris Coffey, Porchlight Elisabeth Garratt, University of Sheffield Tim Sigsworth, AKT Jo Bhandal, AKT Anna Yassin, Glass Door Paul Anders, Public Health England Marike Van Harskamp, New Horizon Youth Centre Burcu Borysik, Revolving Doors Agency Kady Murphy, Just for Kids Law Emma Cookson, St. -

Refugees Welcome? the Experience of New Refugees in the UK a Report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees

Refugees Welcome? The Experience of New Refugees in the UK A report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees April 2017 This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the inquiry panel only, acting in a personal capacity, based on the evidence they received and heard during the inquiry. The printing costs of the report were funded by the Barrow Cadbury Trust. Refugees Welcome? 2 Refugees Welcome? About the All Party About the inquiry Parliamentary Group This inquiry was carried out by a panel of Parliamentarians on behalf of the APPG on Refugees, with support provided by the Refugee Council. The panel consisted on Refugees of members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. They were: The All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees brings together Parliamentarians from all political parties with Thangam Debbonnaire MP (Labour) – an interest in refugees. The group’s mission is to provide Chair of the APPG on Refugees and the inquiry a forum for the discussion of issues relating to refugees, Lord David Alton (Crossbench) both in the UK and abroad, and to promote the welfare of refugees. David Burrowes MP (Conservative) Secretariat support is provided to the All Party Lord Alf Dubs (Labour) Parliamentary Group by the charity The Refugee Council. Paul Butler, the Bishop of Durham For more information about the All Party Parliamentary Group, Baroness Barbara Janke (Liberal Democrat) please contact [email protected]. -

The Rt Hon Theresa May MP Liz Field Review of the Year Review of Parliament

2017 / 2018 FINANCE A YEAR IN PERSPECTIVE FOREWORDS The Rt Hon Theresa May MP Liz Field BROKERAGE, INVESTMENT & FUND MANAGEMENT REPRESENTATIVES Franklin Templeton Investments Opus Nebula BGC’s Sterling Treasury Division Kingsfleet Wealth Stifel Carbon Wise Investment Herbert Scott Stamford Associates FEATURES Review of the Year Review of Parliament ©2018 WESTMINSTER PUBLICATIONS www.theparliamentaryreview.co.uk Foreword Th e Rt Hon Th eresa May MP Prime Minister British politics provides ample material for analysis in the leading in changes to the future of mobility; meeting the pages of The Parliamentary Review. For Her Majesty’s challenges of our ageing society; and driving ahead the Government, our task in the year ahead is clear: to revolution in clean growth. By focusing our efforts on achieve the best Brexit deal for Britain and to carry on our making the most of these areas of enormous potential, work to build a more prosperous and united country – we can develop new exports, grow new industries, and one that truly works for everyone. create more good jobs in every part of our country. We have already made good progress towards our goal Years of hard work and sacrifice from the British people of leaving the EU, so that we take back control of our have got our deficit down by over three quarters. We are laws, money and borders, while negotiating a deep and building on this success by taking a balanced approach special partnership with it after we have left that is good to public spending. We are continuing to deal with our for jobs and security. -

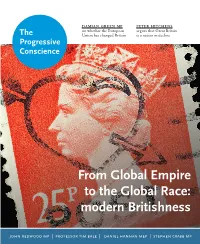

Peter Hitchens on Whether the European Argues That Great Britain the Union Has Changed Britain Is a Nation in Decline Progressive Conscience

DAMIAN GREEN MP PETER HITCHENS on whether the European argues that Great Britain The Union has changed Britain is a nation in decline Progressive Conscience From Global Empire to the Global Race: modern Britishness john redwood mp | professor tim bale | daniel hannan mep | stephen crabb mp Contents 03 Editor’s introduction 18 Daniel Hannan: To define Contributors James Brenton Britain, look to its institutions PROF TIM BALE holds the Chair James Brenton politics in Politics at Queen Mary 20 Is Britain still Great? University of London 04 Director’s note JAMES BRENTON is the editor of Peter Hitchens and Ryan Shorthouse Ryan Shorthouse The Progressive Conscience 23 Painting a picture of Britain NICK CATER is Director of 05 Why I’m a Bright Blue MP the Menzies Research Centre Alan Davey George Freeman MP in Australia 24 What’s the problem with STEPHEN CRABB MP is Secretary 06 Replastering the cracks in the North of State for Wales promoting British values? Professor Tim Bale ROSS CYPHER-BURLEY was Michael Hand Spokesman to the British 07 Time for an English parliament Embassy in Tel Aviv 25 Multiple loyalties are easy John Redwood MP ALAN DAVEY is the departing Damian Green MP Arts Council Chief Executive 08 Britain after the referendum WILL EMKES is a writer 26 Influence in the Middle East Rupert Myers GEORGE FREEMAN MP is the Ross Cypher-Burley Minister for Life Sciences 09 Patriotism and Wales DR ROBERT FORD lectures at 27 Winning friends in India Stephen Crabb MP the University of Manchester Emran Mian DAMIAN GREEN MP is the 10 Unionism -

South East Coast

NHS South East Coast New MPs ‐ May 2010 Please note: much of the information in the following biographies has been taken from the websites of the MPs and their political parties. NHS BRIGHTON AND HOVE Mike Weatherley ‐ Hove (Cons) Caroline Lucas ‐ Brighton Pavillion (Green) Leader of the Green Party of England and Qualified as a Chartered Management Wales. Previously Green Party Member Accountant and Chartered Marketeer. of the European Parliament for the South From 1994 to 2000 was part owner of a East of England region. company called Cash Based in She was a member of the European Newhaven. From 2000 to 2005 was Parliament’s Environment, Public Health Financial Controller for Pete Waterman. and Food Safety Committee. Most recently Vice President for Finance and Administration (Europe) for the Has worked for a major UK development world’s largest non-theatrical film licensing agency providing research and policy company. analysis on trade, development and environment issues. Has held various Previously a Borough Councillor in positions in the Green Party since joining in 1986 and is an Crawley. acknowledged expert on climate change, international trade and Has run the London Marathon for the Round Table Children’s Wish peace issues. Foundation and most recently last year completed the London to Vice President of the RSPCA, the Stop the War Coalition, Campaign Brighton bike ride for the British Heart Foundation. Has also Against Climate Change, Railfuture and Environmental Protection completed a charity bike ride for the music therapy provider Nordoff UK. Member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament National Robbins. Council and a Director of the International Forum on Globalization. -

2001 GA Ann Report.A/W

Printed by Seacourt Press Limited on recycled paper made from 75% de-inked post consumer waste and a maximum of 25% mill broke. Seacourt have EMAS and ISO14001 accreditation, are members of the waterless printing association and their carbon emissions are offset. EMAS registration number UK-5-0000073. annual report 2000/01 our mission Green Alliance exists to promote sustainable development by ensuring that the environment is at the heart of decision-making We work with senior people in government, parliament, business and the environment movement to encourage new ideas, dialogue and constructive solutions. Green Alliance has three main aims: > to make the environment a central political issue > to integrate the environment effectively in public policy and decision-making > to stimulate new thinking and advance the environmental agenda into new areas The publication of this report has been supported by Severn Trent plc and the DEFRA Environmental Action Fund chair’s report Green Alliance’s increased strategic focus over the past two years is paying dividends. Our efforts to engage the Prime Minister and his officials on the environment succeeded, with Tony Blair’s speech to a Green Alliance/CBI audience in October 2000. This was by no means the end of a process, but opened a new dialogue between the Prime Minister and environment groups. Another success was the publication of our detailed, consensual work on the role of negotiated agreements between government and business. This charts a course through opposing views, laying down a model of best practice of which government, business and NGOs can feel ownership. Two Green Alliance pamphlets received considerable attention. -

1 Andrew Marr Show, Damian Green 18 Sept 2016

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, DAMIAN GREEN 18TH SEPT 2016 ANDREW MARR SHOW 18TH SEPTEMBER 2016 DAMIAN GREEN AM: We’ve been talking perhaps rather loosely this morning about a post-liberal era. And one of the headline writers suggest that, compared with the economic liberalism and so forth of past Conservatives, Theresa May represents a break. Do you recognise that language at all? DG: No. I think – I mean clearly liberal capitalism and western values are under threat, they need fighting for, but they always do. I always think this idea we’ve reached the point of the end of history, that Fukuyama analysis at the end of the 80s was optimistic nonsense. You always have to keep fighting for your values. But Theresa May and her government will fight for those broadly small ‘L’ liberal, free market values as hard as any previous Conservative government. AM: So do you see any change of tonal direction in this new government at all? DG: Well, there’s clearly a large element of continuity because we’re all still Conservatives and we’re all modernising conservatives. I think the Conservative Party went through a big change under David Cameron that was necessary and desirable and that element will continue. Of course any new prime minister has their own individual policy priorities, and indeed their own way of doing business and Theresa will do it in a different way. AM: I was going to invite you to explain further since you knew Theresa May for a long, long time. What do you think is the essence of the Theresa May approach? What is new and fresh about it? 2 ANDREW MARR SHOW, DAMIAN GREEN 18TH SEPT 2016 DG: Well, the essence of it is a desire to serve. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 29 November 2018 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. It has been updated to reflect the changes in the Cabinet following the resignations in the aftermath of the government’s proposed Brexit deal. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets. This gives the government a working majority of 13. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. -

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2017 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Prime Minister 5 Attorney General’s Office 6 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy 7 Cabinet Office 11 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 11 Ministry of Defence 13 Department for Education 14 Department of Exiting the European Union 16 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 17 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 19 Department of Health 21 Home Office 22 Department for International Development 23 Department for International Trade 24 Ministry of Justice 25 Northern Ireland Office 26 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 27 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 28 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 29 Scotland Office 30 Department for Transport 31 HM Treasury 33 Wales Office 34 Department for Work and Pensions 35 Government Whips – Commons 36 Government Whips – Lords 40 2 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list, in writing, of all relevant interests known to them, which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate. -

Economy and Industrial Strategy Committee Membership Prime

Economy and Industrial Strategy Committee Membership Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) the Civil Service (Chair) Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the (The Rt Hon David Lidington MP) Cabinet Office (Deputy Chair) Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP) Secretary of State for Defence (The Rt Hon Gavin Williamson MP) Secretary of State for Education (The Rt Hon Damian Hinds MP) Secretary of State for International Trade (The Rt Hon Liam Fox MP) Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP) Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Esther McVey MP) Secretary of State for Transport (The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP) Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local (The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP) Government Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP) Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP) Minister without Portfolio (The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP) Minister of State for Immigration (The Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP) Minister of State for Trade and Export Promotion (Baroness Rona Fairhead) Terms of Reference To consider issues relating to the economy and industrial strategy. Economy and Industrial Strategy (Airports) sub-Committee Membership Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for the (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Civil Service