“Get That Son of a Bitch Off the Field!” Sport in University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

SECTION 05 - HISTORY:Layout 1 11/5/2014 2:07 PM Page 58

SECTION 05 - HISTORY:Layout 1 11/5/2014 2:07 PM Page 58 2014-15 BAYLOR WOMEN’S BASKETBALL MEDIA ALMANAC WWW.BAYLORBEARS.COM 1,000-POINT SCORERS 1. SUZIE SNIDER EPPERS [3,861] 5. MAGGIE DAVIS-STINNETT [2,027] §Baylor's all-time scoring leader with 3,861 points §Ranks No. 5 on Baylor's scoring list with 2,027 points §Baylor's all-time rebounding leader with 2,176 boards §Ranks No. 5 on Baylor's rebounding list with 1,011 rebounds §Inducted into Baylor Athletics Hall of Fame in 1987 §Only player in Southwest Conference history with over 2,000 points and 1,000 rebounds §1977 State Farm/WBCA All-American § Named to Southwest Conference’s All-Decade Team §Three-time first-team All-SWC selection (1988, ‘89, ‘91) Season GP FG-FGA Pct 3FG-A Pct FT-FTA Pct Reb Avg Pts Avg § Ranks No. 3 on SWC’s career scoring list (2,027) 1973-74 31 353 11.4 724 23.4 §Inducted into Baylor Athletics Hall of Fame in 2001 1974-75 42 598 14.2 1011 24.0 1975-76 45 549 12.2 104423.2 Season GP FG-FGA Pct 3FG-A Pct FT-FTA Pct Reb Avg Pts Avg 1976-77 28 486-785 .619 110-151 .728 676 15.4 1082 24.6 1986-87 28 196-438 .434 — — 84-133 .632 227 8.0 476 17.0 Career 162 876-1628 .538 — — 2,176 13.4 3,861 23.8 1987-88 30 254-594 .427 — — 126-190 .663 318 10.6 634 21.1 1988-89 Redshirt 1989-90 22 189-431 .438 — — 76-116 .735 216 9.8 454 20.6 2. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

Notre Dame Athletics

NOTRE DAME Women’s Basketball 2008-09 2001 NCAA Champions • 1997 NCAA Final Four 7 NCAA Sweet 16 Berths • 15 NCAA Tourney Appearances 2008-09 Schedule 2008-09 ND Women’s Basketball: Game 6 5-0 / 0-0 BIG EAST #11/10 Notre Dame Fighting Irish (5-0 / 0-0 BIG EAST) vs. N5 Gannon (exhibition) W, 96-30 Eastern Michigan Eagles (2-4 / 0-0 Mid-American) N16 (16/14) @ LSU (24/22)1-ESPN2 W, 62-53 uDATE: December 2, 2008 uRADIO: Pulse FM (96.9/92.1) N19 (15/15) Evansville W, 96-61 uTIME: 7:00 p.m. ET UND.com N23 (15/15) @ Boston College W, 102-54 uAT: Ypsilanti, Mich. Bob Nagle, p-b-p N25 (14/10) Georgia Southern W, 85-36 Convocation Center (8,824) uLIVE STATS: emueagles.com N29 Michigan State 2:00 ET uSERIES: ND leads 2-0 uTEXT ALERT: UND.com u1ST MTG: ND 75-58 (12/15/82) uTICKETS: (734) 487-2282 D2 @ Eastern Michigan 7:00 ET uLAST MTG: ND 70-59 (11/30/84) D7 Purdue 2:00 ET D10 @ MichiganBTN 7:00 ET Storylines Web Sites D13 @ Valparaiso 1:35 CT u Notre Dame will take on Eastern Michigan u Notre Dame: http://www.UND.com D20 Loyola-Chicago 2:00 ET for the first time in more than 24 years, with u Eastern Michigan: http://www.emueagles.com D28 @ CharlotteESPNU 2:00 ET the Eagles being the lone MAC opponent on u BIG EAST: http://www.bigeast.org D30 @ Vanderbilt 7:00 CT this year’s Irish schedule. -

CFP Edition 01-09-20

75¢ COLBY Thursday January 9, 2014 Volume 125, Number 005 Serving Thomas County since 1888 8 pages FFREEREE PPRESSRESS Challenge kicks off with torch A Quinter doctor showed off mer Olympics. He ran through the the torch he carried for the 2012 English town of Ascot, near Lon- London Olympics as he gave a don, with athletes and nonathletes pep talk Monday to kick off the of all ages. Runners in the relay Thomas County Wellness Chal- pass the Olympic flame between lenge, urging everyone to live gas burners within their torches, healthy in the new year. Gruenbacher said, so they got to Dr. Doug Gruenbacher spoke keep their torches. His had 8,000 to about 35 people Monday in holes in it to represent each of the the Student Union at Colby Com- torchbearers that year. munity College to open the chal- “My kids always say, ‘Oh, this lenge, which starts Monday. The one’s you, Dad,’” he said with a audience heard about his efforts smile. at keeping himself and others The audience got to pass Gru- healthy and fit. enbacher’s torch around as he “Expectations are huge,” Gru- showed pictures of him and his enbacher said. “They (kids) don’t family in England and France. think twice about being physically He did not compete in the active.” games, but is an avid runner who After-school trip to China He said his son Eli had insisted regularly runs in races here. This on running a 10-kilometer race – summer, he said, he ran 50 miles SAM DIETER/Colby Free about six miles. -

18 Lc 117 0073 H. R

18 LC 117 0073 House Resolution 950 By: Representatives Jones of the 53rd, Smyre of the 135th, Gardner of the 57th, Thomas of the 56th, Metze of the 55th, and others A RESOLUTION 1 Recognizing February 14, 2018, as Clark Atlanta University Day at the state capitol, and for 2 other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University was established in 1988 upon the consolidation of its 4 two parent institutions Atlanta University, established in 1865, and Clark College, 5 established in 1869; and 6 WHEREAS, the university's four colleges offer 38 academic programs to roughly 4,000 7 students each year, making a valuable contribution to the future workforce and leadership of 8 Georgia; and 9 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of the Center for Cancer Research and 10 Therapeutic Development which thrives under the leadership of Georgia Research Alliance 11 Eminent Scholar Shafiq A. Khan, Ph.D., and, as such, is the only Historically Black Colleges 12 and Universities (HBCU) member of the Georgia Research Alliance in addition to being the 13 nation's largest academic prostate cancer research center; and as a result of its breakthrough 14 research, presently has five patents and patents pending; and 15 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of Jazz 91.9 FM-WCLK, an NPR affiliate, 16 and is Metro Atlanta community's only jazz radio station and this year celebrates 41 years 17 of service to the community; and 18 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of one of the nation's most prolific 19 undergraduate Mass Media Arts program, responsible for nurturing talent such as Sheldon 20 "Spike" Lee, Nnegest Likke, Jacque Reed, and Eva Marcille; and 21 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of the Center for Functional Nanoscale 22 Materials, the Center for Alternative Energy and Energy Conservation, the Center for 23 Biomedical and Bimolecular Research, and the Center for Cyberspace and Information H. -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

The Conspiracy Issue Pandemic Know-It-Alls 6

THE CONSPIRACY ISSUE PANDEMIC KNOW-IT-ALLS 6 FOURTEEN NEW CONSPIRACY THEORISTS 12 ARE YOU BEING GANG-STALKED? 14 EGOS, ICKE & COVID 16 THE PANDEMIC COOKBOOK 20 THE TALKING DOG CONSPI CY 24 GUENTER ZIMMERMANN 30 THERE IS NO CONSPIRACY 36 DISMANTLING THE 5G MYTH 38 TOP 20 RONA MYTHS 39 MICHAEL JORDANS RETIREMENT 43 STEVIE WONDER IS BLIND NOT 46 MOTIVATIONAL QUOTES FOR CONSPIRACY THEORISTS 50 ROBERT DE NIRO IS A MYTH 52 10 MYTHS ABOUT UNCIRCUMCISED DICKS 56 A PANDEMIC of would? If so, how far do we have points for being obese and el- to wreck the economy to achieve derly? this? To put it another way, how Know-it-Alls many bodies do we have to sac- Do you hoard money, or do you rifice to save the economy? stock up on supplies? If SARS-CoV-2 can actually trav- “We hear plenty about herd im- el in particles of air pollution like munity, but not nearly enough I heard last week, is a lockdown about herd stupidity.” ( ) meaningless, or should we just Should you wear rubber gloves avoid North Jersey? at the gas station, or does that hen it comes to this whole What’s the crude-case fatality make you a Germ Cuck? COVID-19 hall of mirrors rate? What’s the rate of con- Are businesses reopening too W and how we possibly find firmed cases v. suspected total soon to prevent more infections Are “they” all in cahoots, or are our way out if this creepy carni- infections? How many cases are or too late to save the economy? “they” too stupid to pull that off? val exhibit we’re trapped inside closed? How many are still open? hoping it’s not really a cheesy Are they counting people who Would a vaccine apply to every Is it true that the virus can be horror movie made flesh, it seems died outside of hospitals and mutation, or do they have to keep spread through flatulence? that everyone has an answer ex- were never tested for the virus? coming up with new vaccines? Or cept me. -

Ufc 259 Headlined by Three Thrilling World Championship Bouts

UFC 259 HEADLINED BY THREE THRILLING WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP BOUTS Las Vegas – UFC® delivers its most stacked Pay-Per-View event of 2021 so far, headlined by a trio of world championship bouts. Newly crowned UFC light heavyweight championJan Blachowicz makes his first title defense against UFC middleweight champion Israel Adesanya, who aims to become only the fifth fighter to simultaneously hold belts in two UFC weight classes. Two-division titleholder Amanda Nunes puts her UFC featherweight championship on the line against talented striker Megan Anderson. Plus, UFC bantamweight champion Petr Yan looks to take out surging No. 1 contenderAljamain Sterling. UFC® 259: B?ACHOWICZ vs. ADESANYA will take place Saturday, March 6 at UFC APEX in Las Vegas and will stream live on Pay- Per-View, exclusively through ESPN+ in the U.S. at 10 p.m. ET/7 p.m. PT in both English and Spanish. ESPN+ is the exclusive provider of all UFC Pay-Per-View events to fans in the U.S. as part of an agreement announced in 2019. Fans will be able to purchaseUFC ® 259: B?ACHOWICZ vs. ADESANYAonline at ESPNPlus.com/PPV or on the ESPN App on mobile and connected-TV devices. ESPN+ is available as an integrated part of the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Preliminary fights will air nationally in English on ESPN and in Spanish on ESPN Deportes, as well as being simulcast in both languages on ESPN+ starting at 8 p.m. -

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

Baylor's Brittney Griner Headlines 2012-13 Preseason 'Wade Watch' List

Baylor's Brittney Griner headlines 2012-13 preseason 'Wade Watch' list ATLANTA (September 18, 2012) - Baylor center Brittney Griner, the 2012 State Farm® Wade Trophy winner, headlines the 2012-13 preseason "Wade Watch" list of candidates for the prestigious award, the Women's Basketball Coaches Association announced today. Connecticut leads all schools with three players on the 25-member preseason list. Five schools - defending national champion Baylor, Duke, Kansas, Nebraska and Penn State - are represented by two players each. Now in its 36th year, the State Farm Wade Trophy is named in honor of the late, legendary three-time national champion Delta State University coach, Lily Margaret Wade. Regarded as "The Heisman of Women's Basketball," the award is presented annually to the NCAA® Division I Player of the Year by the National Association of Girls and Women in Sport (NAGWS) and the WBCA. The preseason list is composed of top NCAA Division I women's basketball players who best embody Wade's spirit from 18 institutions and eight conferences. A committee of coaches, administrators and media from across the United States compiled the list using the following criteria: game and season statistics, leadership, character, effect on their team and overall playing ability. Notre Dame's Skylar Diggins, Delaware's Elena Della Donne and Georgetown's Sugar Rodgers join Griner on the preseason list for the third straight year. Alex Bentley of Penn State, Carolyn Davis of Kansas, Stefanie Dolson and Bria Hartley of Connecticut, Chiney Ogwumike of Stanford and Odyssey Sims of Baylor are making their second appearance on the list. -

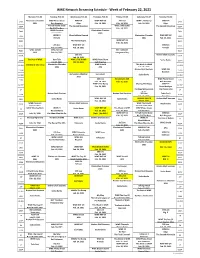

WWE Network Streaming Schedule - Week of February 22, 2021

WWE Network Streaming Schedule - Week of February 22, 2021 Monday, Feb 22 Tuesday, Feb 23 Wednesday, Feb 24 Thursday, Feb 25 Friday, Feb 26 Saturday, Feb 27 Sunday, Feb 28 Elimination Chamber WWE Photo Shoot WWE 24 WWE NXT UK 205 Live WWE's The Bump WWE 24 6AM 6AM 2021 Ron Simmons Edge Feb. 18, 2021 Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 24, 2021 Edge R-Truth Game Show WWE's The Bump 6:30A The Second Mountain The Second Mountain 6:30A Big E & The Boss Feb. 24, 2021 WWE Chronicle Elimination Chamber 7AM 7AM Bianca Belair 2021 WWE 24 WrestleMania Rewind Elimination Chamber WWE NXT UK 7:30A 7:30A R-Truth 2021 Feb. 25, 2021 WWE NXT UK 8AM The Mania Begins 8AM Feb. 25, 2021 205 Live WWE NXT UK WWE 24 8:30A 8:30A Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 18, 2021 R-Truth WWE Untold WWE NXT UK NXT TakeOver 9AM 9AM APA Feb. 18, 2021 Vengeance Day 205 Live Broken Skull Sessions 9:30A 9:30A Feb. 19, 2021 The Best of WWE Raw Talk WWE's THE BUMP WWE Photo Shoot 10AM Sasha Banks 10AM Feb 22, 2021 FEB 24, 2021 Kofi Kingston Elimination Chamber WWE Untold This Week in WWE 10:30A The Best of John Cena 10:30A 2021 APA Feb. 25, 2021 Broken Skull Sessions WWE 365 11AM 11AM Ricochet Elimination Chamber Liv Forever 11:30A Sasha Banks 11:30A 2021 205 Live SmackDown 549 WWE Photo Shoot 12N 12N Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 26, 2010 Kofi Kingston WWE's The Bump Chasing The Magic WWE 24 12:30P 12:30P Feb.