In Pre-Dawn Darkness, the Comair Pilots Chat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

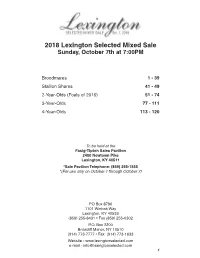

2018 LEX-MIX KY FRONT MATTER 1-32.Pmd

2018 Lexington Selected Mixed Sale Sunday, October 7th at 7:00PM Broodmares 1 - 39 Stallion Shares 41 - 49 2-Year-Olds (Foals of 2016) 51 - 74 3-Year-Olds 77 - 111 4-Year-Olds 113 - 120 To be held at the Fasig-Tipton Sales Pavilion 2400 Newtown Pike Lexington, KY 40511 *Sale Pavilion Telephone: (859) 255-1555 *(For use only on October 1 through October 7) PO Box 8790 1101 Winbak Way Lexington, KY 40533 (859) 255-8431 • Fax (859) 255-0302 P.O. Box 2200 Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510 (914) 773-7777 • Fax (914) 773-1633 Website - www.lexingtonselected.com e-mail - [email protected] 1 CREDITS: Design Greg Schuler Interactive Photos Michael Lisa/Lisa Photo 2 Lexington Selected Yearling Sales Co., LLC Administration Staff Randy Manges ..........................................................Sales Manager David Reid ........................... Sales Manager / Director of Operations Cindy Doyle ........................................................ Sales Administrator Sherry Lane........................................................ Sales Administrator Lillie Brown ...................................................................... Sales Staff Doug Ferris...................................................................... Sales Staff Joan Paynter ................................................................... Sales Staff David Kyle ....................................................... Plant Superintendent Auctioneers James Birdwell, Danny Green and Associates Pedigree Research U.S.T.A. & Lexington Selected Pedigree Research -

Aviation Human Factors Industry News August 2, 2007 Airline

Aviation Human Factors Industry News August 2, 2007 Vol. III. Issue 27 Airline employee dies in accident at Mississippi Tunica Airport The Federal Aviation Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board are looking into the death of a worker at the Tunica Airport. Alan Simpson, a flight mechanic for California- based Sky King Incorporated, died in an accident at the airport on July 10. According to a preliminary NTSB report, Simpson was attempting to close the main cabin door on a flight that was preparing to take off from Tunica when he lost his grip and fell ten feet to the ground. Simpson suffered a skull fracture and broken ribs, and died the next day at The MED. The NTSB report says it was very windy and raining in Tunica that afternoon, but does not say if weather was a factor in Simpson's fall Closing the main cabin door was not part of Simpson's duties. According to a Sky King official, he was doing a favor for a flight attendant. Sky King's president, Greg Lukenbill, called Simpson's death a tragic accident, saying, "he was a highly skilled flight mechanic who dedicated his work to the safety of our aircraft. Al's large personality integrity and big smile will be greatly missed by everyone here at Sky King." The Tunica County Airport Commission's executive director, Cliff Nash, said the airport's insurance company had advised him not to comment on the matter. NTSB Hearing on Flight 5191 For loved ones, 'it is profoundly sad' During a break in the National Transportation Safety Board hearing in Washington, Kevin Fahey reflected on his son’s life. -

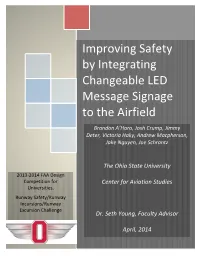

Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield

Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield Brandon A’Hara, Josh Crump, Jimmy Deter, Victoria Haky, Andrew Macpherson, Jake Nguyen, Joe Schrantz The Ohio State University 2013-2014 FAA Design Competition for Center for Aviation Studies Universities, Runway Safety/Runway Incursions/Runway Excursion Challenge Dr. Seth Young, Faculty Advisor April, 2014 COVER PAGE Title of Design: __Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield Design Challenge addressed: __Runway Safety / Runway Incursions / Excursions Challenge_______ University name: ___The Ohio State University_______ Team Member(s) names: __Brandon A’Hara, Josh Crump, Jimmy Deter___________________ _______________________Victoria Haky, Andrew Macpherson, Jake Nguyen, Joe Schrantz____ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ Number of Undergraduates: ____5______________________ Number of Graduates: ________2_______________________ Advisor(s) name: ________Seth Young, Ph.D._______________ 1 | Page FAA Design Competition Entry| A’Hara, Crump, Deter, Haky, Macpherson, Nguyen, Schrantz Executive Summary This report addresses the FAA Design Competition for Universities' Runway Safety/Runway Incursions/Runway Excursion Challenge for the 2013-2014 -

Lexington Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Unified Planning Work Program – Fy 2015 Table of Contents Kytc Unified Planning Work Program (Upwp) Checklist

Unified Planning Work Program “TRANSPORTATION Fiscal Year 2015 PLANNING FOR FAYETTE July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015 Adopted by the Transportation Policy AND Committee on April 23, 2014 JESSAMINE COUNTIES” Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government, Division of Planning, Transportation Planning Section 101 East Vine Street, Suite 700, Lexington, KY 40507 Phone: 859-258-3160 http://www.lfucg.com/AdminSvcs/Planning/TransportPlan.asp http://www.lexareampo.com 0 THE PREPARATION OF THIS FY 2015 UNIFIED PLANNING WORK PROGRAM DOCUMENT WAS FINANCED IN PART BY THE FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION (FHWA) AND THE FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION (FTA) OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION (USDOT) THE KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CABINET (KYTC) THE LEXINGTON-FAYETTE URBAN COUNTY GOVERNMENT (LFUCG) AND JESSAMINE COUNTY, KENTUCKY 1 LEXINGTON AREA METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION UNIFIED PLANNING WORK PROGRAM – FY 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS KYTC UNIFIED PLANNING WORK PROGRAM (UPWP) CHECKLIST ............................................... 3 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................... 4 PURPOSE:.............................................................................................................................. 4 MAP – 21 NATIONAL GOALS.................................................................................................... 4 LEXINGTON AREA MPO ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE ............................................................ 6 LEXINGTON AREA MPO -

Fujii PPS Docu Rvsd Vs101.0 13Aug2019

Research paper on PPS Version 101.0 x modified on 13Aug,2019 x original by Shigeru Fujii on 20Apr, 2017 PPS = Proactive and Predictive System to mitigate/minimize/eliminate PICs fatal decision-making errors by Deep Learning AI PPS SLOGAN = “ Trap Human Errors with PPS “ ① Help pilots trap errors that might occur. ② Do not let errors slip past the “filters” to protect you. ③ Verbalize threats to the rest of the crew. 1 《 I N D E X 》 1. Preface 2. PARADIGM SHIFT Shift from “ James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model ” to “ Shigeru Fujii’s Japanese Rice Cracker Model ” 1.2 PPS (a)PPS concept (GENERAL) (b)PPS development (PARTICULARS) 2. Know where to look first 3. Case Study/Data acquisition 2 4. My Goal of PPS 4.1 PPS outside Cockpit 【Phase-1-A】 4.2 PPS inside Cockpit 4.2.1 PPS inside Cockpit with DARUMA 【Phase-1-B】 4.2.2 PPS inside Cockpit with ULTRAMAN 【Phase-2】 4.3 IDEAL PPS 【Phase-3】 5. Appendix 5.1 Aircraft manufactures strategy on runway incursion 5.1.1 Boeing runway safety strategy 3 5.2 James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management 5.3 Full transcript of Cockpit Voice Recorder of Comair 5191/27Aug,2006 6. Afterword 4 1. Preface PPS is “Proactive and Predictive System to mitigate/minimize/eliminate PICs fatal decision-making errors by Deep Learning AI”. PIC is a captain who is ultimately responsible for his flying aircraft operation and safety during the flight. “PICs fatal decision-making errors” are, naturally speaking, made by PICs. -

A Stamp Analysis of the Lex Comair 5191 Accident

A STAMP ANALYSIS OF THE LEX COMAIR 5191 ACCIDENT Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Human Factors and System Safety Paul S. Nelson LUND UNIVERSITY SWEDEN June 2008 A STAMP ANALYSIS OF THE LEX COMAIR 5191 ACCIDENT Paul S. Nelson 2 Acknowledgements I want to express my sincere gratefulness and appreciation to my professor Sidney Dekker, Lund University School of Aviation. I am forever indebted to him for showing me a new way to think and to look at the world of safety. He has been a patient mentor as I have struggled to let go of old hindsight labeling and develop foresight questioning in its place. It has been an honor to have his supervision and support during the entire master’s course and thesis project. I also want to thank Nancy Leveson, who, through her writings has also been an instructor to me. It is her new model for holistic analysis upon which this thesis is dependant. I want to thank my long time friend and colleague in ALPA safety work, Shawn Pruchniki, for introducing me to the world of Human Factors. It was his introduction that initiated the journey which lead to Sidney Dekker and this master’s degree. Finally, an infinity of thanks goes to my wife and best friend who searched the internet and found the Lund University masters course and encouraged me to apply. Only a teammate would willingly choose what she got herself into by encouraging me to work on my master’s degree. My flight assignments, ALPA safety work, and the Comair 5191 investigation, kept me away from home most of the time. -

Airport Master Plan Update (2013) Executive Summary

Moving Forward AIRPORT MASTER PLAN UPDATE (2013) EXECUTIVE SummaRY Our Planning Partner: In association with: HDR, Inc. GRW, Inc. Integrated Engineering, Inc. CRAWFORD, MURPHY & TILLY, INC. Unison Consulting, Inc. Ailevon, LLC 2013Message AIRPORT FromMASTER The PLAN ExecutiveUPDATE Director As part of our commitment to maintaining safe and comfortable facilities now and in the future, the Airport Board and Staff have invested a significant amount of time into this planning effort. As we operate in a very dynamic industry, it is important that we anticipate changes in aviation so we can continue to develop airport facilities that will serve our customers and the broader air transportation system. The airport’s Master Plan process includes thoughtful forecasting of future activity and plans for an orderly phased development of the airport over time to accommodate that activity. Based on demographics, current airline industry conditions, trends in general aviation, historic growth and economic conditions, the airport and its consulting team have made plans for future facility improvements to accommodate both the immediate and long-term needs of both the com- mercial airlines and our general aviation community. Preparing for these changes now will allow Blue Grass Airport to meet the aviation needs of Lexington and central Kentucky in the future. I encourage you to review our Master Plan and see how these improvements will allow us to operate more efficiently, manage growth responsibly and maintain our role in the community as an economic -

Airliner Accident Statistics 2006

Airliner Accident Statistics 2006 Statistical summary of fatal multi-engine airliner accidents in 2006 Airliner Accident Statistics 2006 Statistical summary of world-wide fatal multi-engine airliner accidents in 2006 © Harro Ranter, the Aviation Safety Network January 1, 2007 this publication is available also on http://aviation-safety.net/pubs/ front page photo: non-fatal MD-10 accident at Memphis, December 18, 2003 © Dan Parent, kc10.net Airliner Accident Statistics 2006 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS .......................................................................................................... 3 SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 4 0. SCOPE & DEFINITION ....................................................................................... 5 1. FATAL ACCIDENTS............................................................................................ 6 1.1 Fatal accidents summary........................................................................ 6 1.2 The year 2006 in historical perspective .................................................... 7 1.3 Regions ............................................................................................... 8 1.3.1 Accident location - countries ................................................................ 8 1.3.2 Accident location - regions................................................................. 10 1.3.3 Operator regions ............................................................................. -

Uk Athletics Facilities

2021-22 VISITORS GUIDE UKAD CONTACT INFORMATION ATHLETIC ADMINISTRATION ......................... (859) 257-8000 BASEBALL ........................................... (859) 257-8052 MEN’S BASKETBALL................................... (859) 257-1916 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL ............................... (859) 257-6046 OPERATIONS.......................................... (859) 218-3716 FOOTBALL ............................................ (859) 257-3611 MEN’S GOLF ........................................... (859) 257-5276 WOMEN’S GOLF ....................................... (859) 257-5276 GYMNASTICS .......................................... (859) 257-5276 COMMUNICATIONS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS .......... (859) 257-3838 RIFLE .................................................(859) 257-1281 MEN’S SOCCER ........................................ (859) 257-1419 WOMEN’S SOCCER .................................... (859) 257-1419 SOFTBALL ...........................................(859). 257-1419 SWIMMING & DIVING................................... (859) 257-7944 MEN’S TENNIS......................................... (859) 257-8052 WOMEN’S TENNIS ..................................... (859) 257-8052 TICKET OFFICE ........................................ (859) 257-1818 TRACK & FIELD ........................................ (859) 257-5276 TRAINING ROOM....................................... (859) 257-6521 VOLLEYBALL .......................................... (859) 257-2532 EMERGENCY LISTINGS Central Baptist Hospital . (859) 260-6100 1740 Nicholasville Road -

NOTICE Template

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N 8900.118 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Effective Date: National Policy 05/11/10 Cancellation Date: 05/11/11 SUBJ: Approved Airplane Cockpit Takeoff List 1. Purpose of This Notice. This notice provides guidance to ensure that pilots confirm that they are lining up for takeoff on the correct runway. 2. Audience. The primary audience for this notice is principal operations inspectors (POI) assigned to Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 121 and part 135 certificate holders, part 125 operators, and program managers assigned to part 91 subpart K (part 91K) operators. The secondary audience includes Flight Standards branches and divisions in the regions and in headquarters. 3. Where You Can Find This Notice. You can find this notice on the MyFAA Web site at https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. Inspectors can access this notice through the Flight Standards Information Management System (FSIMS) at http://fsims.avs.faa.gov. Operators and the public may find this information at: http://fsims.faa.gov. 4. Background. a. Comair Flight 5191 Accident. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued Safety recommendation A-07-044 following the investigation of the Comair Flight 5191 accident. On August 27, 2006, Comair Flight 5191 attempted to takeoff from the wrong runway at Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky. b. NTSB Recommendation A-07-044. The recommendation requires that: “all 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91K, 121, and 135 operators establish procedures requiring all crewmembers on the flight deck to positively confirm and cross check the airplane’s location at the assigned departure runway before crossing the hold-short line for takeoff. -

Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum 4721 Aircraft Drive Anchorage, AK 99502 (907) 248-5325 (Ph) (907) 248-6391 (Fax) Home Page

Aviation Museums in the United States If your favorite aviation museum is not listed correctly, please contact the Curator of the Planetarium at the Lafayette Science Museum so the listing can be added or corrected! Don’t forget to check a museum’s hours before visiting—some are open only part-time. Checking ahead for times and requirements can be particularly important for museums on active military bases. Alaska Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum 4721 Aircraft Drive Anchorage, AK 99502 (907) 248-5325 (ph) (907) 248-6391 (fax) Home page: http://www.alaskaairmuseum.com/ Alaskaland Pioneer Air Museum 2300 Airport Road Fairbanks, AK 99707 (907) 451-0037 Home page: http://www.pioneerairmuseum.org Alabama Southern Museum of Flight 4343 73rd St. N. Birmingham, AL 35206 (205) 833-8226 (ph) (205) 836-2439 (fax) Home page: http://www.southernmuseumofflight.org/ United States Army Aviation Museum Ft. Rucker, AL 26262 (334) 598-2508 (ph) Home page: http://www.armyavnmuseum.org/ 433 Jefferson Street, Lafayette, LA 70501, 337-291-5544, www.lafayettesciencemuseum.org USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park 2703 Battleship Parkway Mobile, AL 36602 (251) 433-2703 (ph) Home page: http://www.ussalabama.com/ Arkansas Arkansas Air and Military Museum 4290 South School Street Fayetteville, AR 72701 (479) 521-4947 (ph) Home page: http://www.arkansasairandmilitary.com/ Arizona Kingman Army Airfield Historical Society & Museum 4540 Flightline Drive Kingman, AZ 86401 (928) 757-1892 Home page: http://kingmanhistoricdistrict.com/points-of-interest/army-air-field- museum/index.htm -

Business Prospectus

Contact Information Commerce Lexington Inc. is the business organization for the Bluegrass. Con- Phone: (800) 341-1100 or (859) 225-5005 sisting of the Chamber of Commerce, Commerce Lexington Economic Develop- ment, and the Business Education Network, Commerce Lexington Inc. works Web: locateinlexington.com with the local government and surrounding communities to enhance business and economic development opportunities in and around the Lexington area. Email: [email protected] The material contained within this prospectus is designed to provide you with basic information to evaluate the Lexington area as a business location. The information contained in this document is verified to be accurate at the time of publishing. The professional staff of Commerce Lexington Inc. is prepared to assist you by providing specific information based upon your project's requirements. We would be happy to help you make the Bluegrass your new home. Updated September, 2019 Commerce Lexington Inc. Social Media Links Robert L. Quick, CCE Economic Development President and CEO 859-226-1616 [email protected] www.facebook.com/locateinlex Gina Greathouse Executive Vice President, Economic Development 859-226-1623 [email protected] www.linkedin.com/company/commerce-lexington- economic-development Hannah Crumrine Senior Project Manager, Economic Development 859-226-1631 [email protected] www.twitter.com/locateinlex Tyrone Tyra Senior Vice President, Community and Minority Business Development 859-226-1625 [email protected]