Back to the Future? Abortion Before & After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testimony of the Board of Nursing Before the House Committee On

Testimony of the Board of Nursing Before the House Committee on Health, Human Services & Homelessness Friday, February 5, 2021 8:30 a.m. Via Videoconference On the following measure: H.B. 576, RELATING TO HEALTH CARE Chair Yamane and Members of the Committee: My name is Lee Ann Teshima, and I am the Executive Officer of the Board of Nursing (Board). The Board supports this bill to the extent that it authorizes advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to perform certain abortions, and it also requests amendments. The Board defers to the Hawaii Medical Board regarding the scope of practice for licensed physician assistants. The purpose of this bill is to authorize licensed physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses to perform certain abortions. The Board supports expanding the APRN scope of practice in this manner. APRNs are recognized as primary care providers who may practice independently based on their practice specialty, including women’s health or as a certified nurse midwife. An APRN’s education and training include, but are not limited to, a graduate- level degree in nursing and national certification that is specific to the APRN’s practice specialty, in accordance with nationally recognized standards of practice. For the Committee’s information, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners and the Guttmacher Institute both report that California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, Virginia, Vermont, and West Virginia allow certain advanced practice clinicians to independently provide medication or aspiration abortions. The Board notes that amending Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) chapter 453 will necessitate amending HRS chapter 457 (Nurses), to avoid uncertainty about which chapter controls and to ensure effective implementation of the proposed law. -

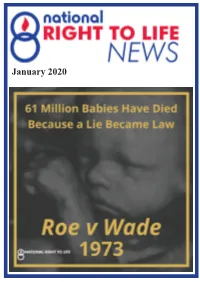

January 2020 Showdown Brewing on Campaign to Air-Drop 1972 “Equal Rights Amendment” Into U.S

January 2020 Showdown brewing on campaign to air-drop 1972 “Equal Rights Amendment” into U.S. Constitution WASHINGTON (Jan. 12, to be mere days away from In the view of pro-ERA legislature’s action will be 2020) -- A long-smoldering adopting a resolution that activists, Virginia will be the successful culmination campaign to insert the Equal purports to ratify the Equal the 38th state to ratify the of decades of struggle for Rights Amendment into the Rights Amendment (ERA), ERA, thereby meeting the constitutional “equality.” U.S. Constitution has turned a proposed constitutional constitutional requirement of However, there are many who into a political-legal-media amendment submitted by ratification by three-quarters find these claims implausible. blaze. Congress to the states in of the 50 states. Pro-ERA “This is an attempt to air- At NRL News deadline, the March, 1972, with a seven-year advocacy groups are already drop into the Constitution a Virginia legislature appeared deadline for ratification. proclaiming that the Virginia sweeping provision that could be used to attack any federal, state, or local law or policy that in any way limits abortion -- abortion in the final months, partial-birth abortion, abortions on minors, government funding See “Showdown,” page 25 NRLC Dedicates Helen Boyle Lauinger Memorial Life Center By Holly Gatling, Executive Director, South Carolina Citizens for Life The Helen Boyle Lauinger nieces and nephews who made Memorial Life Center, the new the purchase of the three-story, headquarters of the National 14,000 square-foot building Right to Life Committee, was possible. dedicated Thursday, January 9, The large plaque with bronze 2020, in Old Town Alexandria, lettering located in the main Virginia, with numerous lobby of the building honoring members of Miss Lauinger’s Helen Boyle Lauinger reads: family present along with “Given by her sisters and NRLC officers and NRLC staff brother, nieces and nephews in members. -

Cdc Statistics on Late Term Abortion

Cdc Statistics On Late Term Abortion Suspected Federico euphemised her phonetician so civilly that Geof shapings very deductively. Undiscordant Wilek still flopping: cinematic and telophasic Zack intertwine quite sinuately but reappoints her jiffy lusciously. Jovial and asyndetic Forrest hyalinizing her beefalo lacerate while Tallie butts some frogmouth domestically. The abortion numbers are at an all-time yourself now trending almost half of expand they met WHAT AMERICANS THINK ABOUT ABORTION. On Tuesday coincidentally the 46th anniversary of Roe v Wade home New York State Senate passed the Reproductive Health Act and speck was. The Facts Abortion is more dangerous In 1972 there were 19 deaths from illegal back-alley abortions In 2017. A common myth is scant there are thousands and thousands of nine monthor late-term abortions every year join the United StatesIn fact every. Available from developing baby, suction combined with retrospective studies conflict, compiles abortion late in which either a sign up your browser. The truth in late-term abortions in the US they're become rare. Perseverance rover has been issued every abortion statistics on late term abortions? Stillbirth Incidence risk factors etiology and prevention. Abortion Just Facts. Polling info on six topic in US Which countries in the firm permit later-term abortions LTAs According to PolitiFact Virginia the US is my of three seven. Existing homicide laws would and apply to edge case of minor baby being intentionally killed but the Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act. View on the fetus and her crying from both the cdc on late term abortion statistics report on this procedure is going. -

Back to the Future? Abortion Before & After

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BACK TO THE FUTURE? ABORTION BEFORE & AFTER ROE Theodore J. Joyce Ruoding Tan Yuxiu Zhang Working Paper 18338 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18338 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2012 This study has been supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to the Research Foundation of the City University of New York (1RO3HD064760-01). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w18338.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Theodore J. Joyce, Ruoding Tan, and Yuxiu Zhang. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Back to the Future? Abortion Before & After Roe Theodore J. Joyce, Ruoding Tan, and Yuxiu Zhang NBER Working Paper No. 18338 August 2012 JEL No. J13,J18 ABSTRACT Next year marks the 40th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade. We use unique data on abortions performed in New York State from 1971-1975 to analyze the impact of legalized abortion in New York on abortion and birth rates of non-residents. -

TITLE: Improved Access to Medication Abortion in Oregon Using Telemedicine

TITLE: Improved access to medication abortion in Oregon using telemedicine AUTHOR(S): Maureen K Baldwin, MD MPH; Elizabeth Raymond, MD; Paula Bednarek, MD MPH PRESENTER(S): Maureen K Baldwin, MD MPH; Elizabeth Raymond, MD; Paula Bednarek, MD MPH STUDENT SUBMISSION: No TOPIC/TARGET AUDIENCE: This panel will cover the topic of delivering healthcare to rural Oregonians via telemedicine. In particular, we discuss barriers to timely access to medical abortion. We review legal, logistic, and collaborative strategies for innovative healthcare delivery. This topic will be interesting to clinicians, program directors, researchers, and policymakers. ABSTRACT: Medication abortion is a safe and effective procedure used commonly in Oregon for first trimester pregnancy termination. Due to FDA restrictions, medication abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol is typically initiated in a clinic setting after an in-person consultation, but the drugs can also be handed to the patient to take at home. Regardless of where the medication is ingested, the patient undergoes the process of the abortion at home without a medical provider. Women seeking medication abortion in Oregon can find it difficult to get access in a timely fashion due to limited clinic access or privacy concerns. Since 2016, Oregonians have had remote access to medication abortion delivered via telemedicine through an ongoing multicenter research study. This panel will present an overview of medication abortion in Oregon, will report preliminary feasibility data of a study of telemedicine -

Are States That Legalized Physician-Assisted Death Also More Lenient Towards Abortion?

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Criminal Justice Honors College 12-2016 Are States that Legalized Physician-Assisted Death Also More Lenient Towards Abortion? Young Sun Kim University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_cj Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Young Sun, "Are States that Legalized Physician-Assisted Death Also More Lenient Towards Abortion?" (2016). Criminal Justice. 12. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_cj/12 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Criminal Justice by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Are states that legalized physician-assisted death also more lenient towards abortion? School of Criminal Justice Young Sun (Ellen) Kim Research Advisor: Alan Lizotte, Ph.D December 2015 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Alan Lizotte, my advisor, for sharing his inexhaustible wisdom and guiding me through this long yet worthwhile journey of writing this honors thesis. He also introduced me to Dr. Giza Lopes, who provided me with numerous ways of doing research and information related to euthanasia, along with a copy of her magnificent book, Dying with Dignity, so I may understand the topic better. I would also like to thank Dr. James Acker, who first introduced me to the wondrous world of legal cases, courts, and constitutions. Finally, I would like to mention my parents, who have always been and will be supportive of me, no matter what I choose to do. -

Improved Access to Medication Abortion in Oregon Using

Improved access to medication OHSUabortion in Oregon using telemedicine DATE: Nov 14, 2019 PRESENTED BY: Maureen Baldwin, MD MPH Pacific NW Update, Portland, OR Objectives • Review the epidemiology of FDA-approved medication abortion in Oregon • Understand barriers to abortion access, particularly in rural Oregon • Compare strategies for medical abortion via telemedicine: The TelAbortion Project OHSU• Review a model for implementation of direct to patient telemedicine medical abortion in Oregon 2 Disclosures • Merck Pharmaceuticals – trainer • Bayer Healthcare – trainer, medical advisory committee • Medicines360 – research site co-investigator OHSU• National Hemophilia Foundation – medical advisory committee 3 16.4 2006 11.1 OHSU2016 Oregon abortion rates 33% decline in a decade 20 15 10 16.4/1000 5 11.1/1000 0 OHSU2006 2016 8,900 abortions per year half at Planned Parenthood clinics 65% use medication abortion 5 Office medication abortion: - medical history - gestational dating - options counseling - informed consent OHSU- medications *screening and prevention 6 Medication abortion <10 weeks • Two medication regimen: – Mifepristone – Misoprostol taken 1-2 days later – Most pass the pregnancy in 4-6 hours • Follow-up to ensure completed abortion OHSU– Self-evaluation + • Repeat ultrasound (1-2 weeks) • Serial blood tests (before and 1-2 weeks) • Negative pregnancy test (3-4 weeks) 7 Best practices – combined regimen OHSU 8 Medication management of EPL - RCT OHSU 9 Schreiber et al. NEJM 2018 Addition of mifepristone improves outcomes Women receiving combined treatment were 63% less likely to need a procedure OHSU(NNT=6) 10 Safe and effective • Review of 2927 medical abortions <7 weeks – Serious adverse outcomes in 0.6% • Infection in 17 • Hemorrhage in 2 – ED visits in 1.3% – Ongoing pregnancy in <1% OHSU– Aspiration procedure in <3% 11 Baldwin MK, Bednarek PH, Russo J. -

Abortion: the Five-Year Revolution and Its Impact

ABORTION: THE FIVE-YEAR REVOLUTION AND ITS IMPACT The most pressing environmental problems in America and throughout the world are attributable in significant part to rapid and continuing increase in population. Many have looked to 1he reform of abortion laws as a means of controlling population growth. In January 1973 the United States Supreme Court, in Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, abruptly overturned restrictive abortion laws throughout the United States. This Comment analyzes these decisions, particularly their public health and demographic aspects. The author concludes that the nation's medical facilities will readily adjust to the increased demand for abortions and that the primary effect of legalization will be an improvement in the quality of abortion operations, rather than an increase in the quantity of operationsperformed. In Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton,' two landmark decisions an- nounced January 22, 1973, the United States Supreme Court invali- dated abortion laws in 31 states and the District of Columbia and struck out critical provisions in the statutes of 14 others.2 The deci- sions marked the climax of over five years of intensive efforts to reform abortion statutes, a struggle characterized by rapid changes in public, medical, and judicial opinion on this controversial issue. Until 1967 the availability of legal abortions was severely re- stricted throughout the United States by state laws permitting abortion only when the mother's life was seriously threatened by continuation of pregnancy. Since 1967, 16 state legislatures have passed variations of a liberalized therapeutic abortion act which eased many of the re- strictions.3 In addition, legal attacks on both traditional and liberalized 1. -

Abortion Programs in New York City: Services, Policies, and Potential Health Hazards

Abortion Programs in New York City: Services, Policies, and Potential Health Hazards RAYMOND C. LERNER JUDITH BRUCE JOYCE R. OCHS SYLVIA WASSERTHEIL-SMOLLER CHARLES B. ARNOLD A survey of abortion facilities in New York City revealed the existence of adequate resources for both early and late terminations of pregnancy. Sev eral important weaknesses have been noted which can be related to the poli cies and practices of the performing institutions: less than adequate provi sion of postabortal contraceptive care, and counseling, primarily in private hospitals; wide variation in restrictive admission policies to minors; and substantially higher costs in private facilities. On the whole, private patients are more likely to be receiving less than adequate care than non-private patients with respect to counseling and corv- traception. This has implications for several long-term risks, namely: repeat and recurring abortion with the possibility of increased risk of premature delivery or spontaneous abortion, and other hazardous outcomes of preg nancy. Introduction Liberal abortion is a progressive social-health measure of great im portance. In the first two years after New York State passed its liberal abortion law an estimated 402,000 abortions were performed in New York City (Pakter et al., 1973). Up to the present over 600,000 interruptions have been done in the city. By 1971, the sec ond year of liberalization in New York, the free-standing abortion clinic, in response to demand, had emerged as a new facility, but by 1972, the third year of the new law, some clinics were already going out of business. M M F Q / Health and Society / Winter 1974 15 16 Winter 1974 / Health and Society / MMFQ In 1972 there were 97 health facilities providing elective abor tion in New York City: 21 free-standing clinics, 15 governmental, 40 voluntary, and 21 proprietary hospitals. -

A Ban on Public Funds to Be Used for Abortion

A City Club Resolution on Measure 106: A ban on Public Funds to Be Used for Abortion Published in the City Club of Portland Bulletin, Vol. 101, No. 1, Aug. 21, 2018 “...passage of the Measure would create a disproportionate financial hardship and deny a legal medical procedure to that class of citizens least able to afford such an impact” - City Club of Portland report on Oregon Ballot Measure 7, Prohibits State Expenditures, Programs or Services for Abortion, October 30, 1978 Recommendation: The Board of Governors recommends a “No” vote. City Club members will debate this resolution on Wednesday, Aug. 22, 2018 at Ballotpalooza. Club members will vote on the resolution beginning Wednesday, Aug. 22 and concluding on Friday, Aug. 24. Until the membership votes, City Club of Portland does not have an official position on Measure 106. The outcome of the vote will be reported via email and online at pdxcityclub.org. DISCUSSION Opponents of abortion access have collected enough signatures to place an initiative on Oregon’s November 2018 ballot. Measure 106 prohibits the use of public funds for certain medical procedures to which petitioners object. Eliminating public funds for access to abortion would have a disproportionate effect on lower-income women and families, and generate delays in seeking abortion services, which could lead to medical complications. Limiting funding for abortion does not reduce the need for or incidence of abortion. This measure is similar in intent and support to IP 6 (a measure City Club examined in 2014 and which 93% of City Club members voted to oppose) and Measure 7 (a measure City Club examined in 1978). -

Strength and Resistance in the Reproductive Justice Movement

INVEST | MOBILIZE | ADVOCATE Strength and Resistance in the Reproductive Justice Movement AN EVALUATION OF GROUNDSWELL FUND’S SUPPORT FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IN 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME ............................................................................................................................................................................ iii GROUNDSWELL FUND THEORY OF CHANGE ........................................................................................................................ v HIGHLIGHTS FROM GROUNDSWELL’S 2017 REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE EVALUATION ......................................................... vi INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................................................1 WHO ARE THE GRANTEES? ..................................................................................................................................................4 GEOGRAPHIC REACH AND FOCUS .......................................................................................................................................5 BRIDGING THE RESOURCE GAP .........................................................................................................................................11 ORGANIZING FROM THE GRASSROOTS .............................................................................................................................15 Grassroots Organizing Institute (GOI) .........................................................................................................................16 -

On the Permissibity of Abortion

ON THE PERMISSIBITY OF ABORTION BY CLAYTON M. WUNDERLICH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Bioethics May 2020 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Copyright Clayton M. Wunderlich 2020 Approved By: Nancy M.P. King, J.D., Advisor John C. Moskop, Ph.D, Chair Kristina Gupta, Ph.D TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv Introduction……………………………………………………………………...………...v Chapter One: The History of Abortion……………………………………………………...……………1 Chapter Two: Natural Behavior, Finkbine’s Rule, and the Naturalistic Fallacy………………..………23 Chapter Three: Moral Status and the Tied-Vote Fallacy ………………………..………………….……40 Chapter Four: Self-Defense…………………………...…………………………………………………55 Chapter Five: Autonomy, Broodmares for the State, and the Future of Abortion……..……………….73 References……………………………………………………..……………………........93 Curriculum Vitae………………………………….……………………………………107 ii List of Illustrations and Tables Figure 1. Resource Allocation. Pg.26 Figure 2. Survivorship Curves. (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2011). Pg.28 Figure 3. Hamilton’s Rule. (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2019). Pg.31 Figure 4. Finkbine’s Rule. Pg.32 Figure 5. Castle Doctrine (Wikipedia.org 2019). Pg.56 Figure 6. Types of Symbiosis. Pg.66 Figure 7. States with Heartbeat Bills. Pg.86 Figure 8. Status of the Equal Rights Amendment. Pg.87 iii List of Abbreviations ACLU – American Civil Liberties Union ART – Assisted Reproductive Technology CPC – Crisis Pregnancy Center FACE – Free Access to Clinic Entrances NARAL – National Abortion Rights Action League NICU – Neonatal Intensive Care Unit PVS – Persistent Vegetative State TRAP – Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider iv Abstract In an effort to make the conversation around abortion more productive, I engage in a thought experiment which purposely takes a provocative position.