Re-Examining North Tyneside Community Development Project and Its Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jarrow REC Office Annual Report Summary April 2016 to March 2017

Jarrow REC Office Annual Report Jarrow REC Office Annual Report Summary April 2016 to March 2017 Purpose To present a summary of the annual reports from Research Ethics Committees (RECs) managed from the Jarrow REC Office. The reports cover the activity between April 2016 and March 2017 and copies of the full reports are available on the HRA website. Recommendations That the annual reports be received and noted Presenter Catherine Blewett Research Ethics Manager Email address: [email protected] Contact Regional Manager – Hayley Henderson RECs Email address: [email protected] London – Camden and Kings Cross REC Manager: Christie Ord Email: nrescommittee.london- [email protected] North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 REC Manager: Gillian Mayer Email: nrescommittee.northeast- [email protected] North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 REC Manager: Kirstie Penman Email: nrescommittee.northeast- [email protected] North East – Tyne and Wear South REC Manager: Ryan Erfani-Ghettani Email: [email protected] North East – York REC Manager: Helen Wilson Email: [email protected] Yorkshire & the Humber – Bradford Leeds REC Manager: Katy Cassidy Email: nrescommittee.yorkandhumber- [email protected] Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds East REC Manager: Katy Cassidy Email: [email protected] 1 | P a g e Jarrow REC Office Annual Report Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds West REC Manager: Christie Ord Email: [email protected] Yorkshire & the Humber – Sheffield REC Manager: Kirstie Penman Email: [email protected] Yorkshire & the Humber – South Yorkshire REC Manager: Helen Wilson Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION: The Health Research Authority (HRA) is a Non Departmental Public Body, established initially as a Special Health Authority on 1 December 2011. -

Get Sponsored to Sleep Rough So Others Don't

Get sponsored to sleep rough so others don’t have to YMCA North Tyneside Sleep Easy 2020 Friday the 27th of March Thank you for signing up to take part in Sleep Easy 2020! Now that you are part of the team we wanted to tell you a little bit more about why it is such a vital event for a charity like YMCA. Did you know? • It was estimated in 2013/14 that 64,000 young people were in touch with homelessness services in England, more than four times the number accepted as statutorily homeless. • Current Jobseekers’ Allowance rates for under 25s are £57.90 per week, as compared with £73.10 for those aged 25 and over. Young people’s weekly allowance is therefore significantly less than that for adults aged 25 and over. Recent welfare reforms have had a significant Over the last impact on young people’s housing and shared accommodation is becoming the most or only 12 months affordable option. There is an ever growing demand for a safe, warm and nurturing environment for young people to have the opportunity to develop; but thanks to fundraising events like this we have been able to increase our bed spaces by 40% over the last 12 months. 2 - YMCA North Tyneside - Sleep Easy Participation Pack 2019 Fundraising As we are trying to raise as much money as possible for our Supported Accommodation projects, we are encouraging you all to get your friends and family to sponsor you for taking part in Sleep Easy! We’ve set a target of £10,000 – But let’s see if we can raise more! £¤ ¥¦ ¢ § ¡¢ £¨ ¤© ©¡ £ •F ¡ ¢£ our website at ymcanorthtyneside.org/sleep-easy/ to sign up and pay your y ¥¦ © ¢ £© ¥ ¢ ¦¥ ¡ £10 entry fee. -

694/700 Coventry Road, Small Heath, Birmingham, B10 0TT

694/700 Coventry Road, Small Heath, Birmingham, B10 0TT LEASE FOR SALE FULLY FURNISHED/EQUIPPED HIGH QUALITY RESTAURANT FACILITY 4,500 sq.ft/422.7 sq.m • Occupying a prominent corner position, enjoying substantial frontages onto both Coventry Road and Mansel Road • All internal fixtures and fittings/equipment, included within the lease sale • Recently refurbished to an extremely high standard. • Circa 160 covers • Takeaway facility • Off street car parking-circa 16 spaces Stephens McBride Chartered Surveyors & Estate Agents One, Swan Courtyard, Coventry Road, Birmingham, B26 1BU Tel: 0121 706 7766 Fax: 0121 706 7796 www.smbsurveyors.com 694/700 Coventry Road, Small Heath, Birmingham, B10 0TT LOCATION (xv) Refrigerated cabinets (xvi) Griddles The subject premises occupies an extremely prominent corner position, (xvii) Stainless steel sinks with drainers situated at the intersection of the main Coventry Road (considerable (xviii) Walk in chiller traffic flow)and Mansel Road. (xix) Walk in freezer The property is located at the heart of the main retail centre serving TENURE the local community. The property is available on the basis of a twenty year, FRI Lease Surrounding areas are densely populated residential. agreement (five year review pattern). Small Heath park is located directly opposite. ASKING RENTAL LEVEL The area adjoins the main Small Heath Highway (A45). £65,000 per annum exclusive Birmingham City Centre is situated approximately 3.5 miles north west. RENTAL PAYMENTS DESCRIPTION Quarterly in advance. The subject premises comprise a relatively modern, recently BUSINESS RATES refurbished to an extremely high standard, predominantly ground floor, fully equipped restaurant facility. Current rateable value £64,000 Rates payable circa £31,360 Advantages include: PREMIUM OFFERS (i) Circa 160 covers (ii) Fully air conditioned - hot & cold Offers in excess of £85,000 are invited for this valuable leasehold (iii) Private function room interest, including all internal fixture's and fittings/equipment. -

Cobalt-Newcastle.Pdf

North Tyneside Council Cobalt 14, Quicksilver Way, North Tyneside NE27 0QQ Modern Government Let Office Investment Long Unexpired Lease Term with Annual Rent Reviews • Located on Cobalt Business Park, in Newcastle, with easy access to the A1 dual carriageway via the A19 dual carriageway. • Built in February 2007, the property comprises a modern, well specified office building totalling approximately 46,136 sq ft (4,286 sq m). • The property is offered on a long leasehold basis with an unexpired term of 108 years at an annual peppercorn rent. • Entirely let to North Tyneside Council on a 23 year term from 1st July 2009 (with currently around 19 years unexpired) . • The property is let on a Lease Plus Agreement with a total current income of £878,981 per annum. • Under the Lease Plus Agreement the total initial rent payable is apportioned 68% to the base occupational rental income and 32% for the Facilities Management Service provision. • The 68% base Occupational Income is subject to fixed annual increases of 2.6% per annum and currently amounts to £586,914 per annum (£12.72 per sq ft). The 32% FM element is subject to annual increases in line with the movement in RPIx. • In addition to the Income received from North Tyneside Council, the landlord also benefits from a Rental Top Up which is held in an escrow account. The total value of the cash pot amounts to approximately £790,000 and is released on a monthly basis. For 2013 the annual top up amounts to £150,869. • By virtue of a renegotiated FM Service contract, the landlord also y benefits from a saving by virtue of receiving a higher annual FM r payment from North Tyneside Council when compared with the actual cost of the FM service provided. -

Spring Into Summer

Spring into Summer Spring into Summer is our fourth virtual activity programme. This seven week programme runs from 17th May to 2nd July and features a range of physical and social activities to keep you entertained this summer. To sign up for any of our activities, call us on 0191 287 7012 or email us at [email protected] Weekly Events Drop in just once, or become a regular! However often you join, these activities will help you build skills and gain knowledge to lead a more healthy and active life. Tai Chi Mondays at 1pm Fridays at 2.30pm Tai chi relaxes the mind and body, helping to combat the stresses and strains of modern society. It gently tones and strengthens muscles. It also improves balance, posture and helps prevent falls. This can help older people with disabling health conditions. The class involves slow, relaxed, flowing, mindful movements, which makes it adaptable to many levels of health and fitness. Healthy Habits Keep Fit with Maureen Thursdays at 12.30pm Thursdays at 1pm Join our Healthy Habits team for a A 45 minute dance and low impact keep fit class to series of talks covering a variety of suit all abilities. A fun class exercising to music and topics, including mood, meditation working to your own ability. Includes a short strength and diet. There will even be some section using light hand weights, water bottles or cooking demos! flexi bands; finishing with a stretch and cool down. One-Off Events Don’t miss out! These events are one-off talks and activities with a range of guest speakers. -

North Tyneside Infrastructure Delivery 2017

North Tyneside Council Infrastructure Delivery Plan August 2017 North Tyneside Infrastructure Delivery 2017 Contents Table of Figures.......................................................................................................................2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................3 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................4 2 Methodology.................................................................................................................. 11 3 Transport ....................................................................................................................... 12 4 Community Facilities.................................................................................................... 29 5 Utility Services ................................................................................................................... 36 6 Waste Management ......................................................................................................... 39 7 Water/Flooding .................................................................................................................. 44 8 Open Space .................................................................................................................. 49 9 Health ............................................................................................................................ -

North Tyneside Council

W C A U E C H M D B 5 y L R L A R E E A N A 0 N D L M IN P R G R 5 M FO O B I U S E R O Y LA N T W 1 R W O E O N A D H E E B H R O H D T U C O T Y D L A B S Seaton W R O L R R CLIF STO T E E R C N TO I E R L O N R R IF T RO B Seaton W AD H S R L O C A A G LI O E FT W L O T M C N N R E H O A D A A 26 O 27 D A S 22 23 24 25 28 29 30 31 32 33 R D 34 35 36 37 D F E 1 A E O M U NWO L ORWI 7 OD DR W R CK C N IVE Sluice 1 elcome to the new North Tyneside cycling map, and its OAD E IN D V 1 R C R W A M L W E E E MEL EA B A 0 O O A K L I R E S 9 IDG E C TON L S E ID 1 L P C A L A D V A E R S T I E E A F E E I CY TR H N E R S E D S E U L P I A M C R E EL M P surrounding area. -

Royal Quays Marina North Shields Q2019

ROYAL QUAYS MARINA NORTH SHIELDS Q2019 www.quaymarinas.com Contents QUAY Welcome to Royal Quays Marina ................................................. 1 Marina Staff .................................................................................... 2 plus Marina Information .....................................................................3-4 RYA Active Marina Programme .................................................... 4 Lock Procedure .............................................................................. 7 offering real ‘added value’ Safety ............................................................................................ 11 for our customers! Cruising from Royal Quays ....................................................12-13 Travel & Services ......................................................................... 13 “The range of services we offer Common Terns at Royal Quays .................................................. 14 A Better Environment ................................................................. 15 and the manner in which we Environmental Support ............................................................... 15 deliver them is your guarantee Heaviest Fish Competition ......................................................... 15 of our continuing commitment to Boat Angling from Royal Quays ................................................. 16 provide our berth holders with the Royal Quays Marina Plan .......................................................18-19 Eating & Drinking Guide ............................................................ -

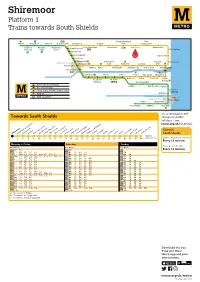

Shiremoor Platform 1 Trains Towards South Shields

Shiremoor Platform 1 Trains towards South Shields Northumberland West Airport Bank Foot Fawdon Regent Centre Longbenton Benton Park Monkseaton Four Lane Ends Palmersville Shiremoor Monkseaton Callerton Kingston Wansbeck South Gosforth Parkway Park Road Whitley Bay Ilford Road West Jesmond Cullercoats Jesmond Haymarket Chillingham Meadow Tynemouth Newcastle City Centre Monument Road Wallsend Howdon Well St James Manors Byker Walkergate Hadrian Road Percy Main North Shields Central Station River Tyne Gateshead Felling Pelaw Jarrow Simonside Chichester Hebburn Bede Tyne Dock South Heworth Gateshead Shields Stadium Brockley Whins Main Bus Interchange Fellgate East Boldon Seaburn Rail Interchange Ferry (only A+B+C tickets valid) Stadium of Light Airport St Peter’s River Wear Park and Ride Sunderland City Centre Sunderland Pallion University South Hylton Park Lane These timetables will Towards South Shields change on public holidays - see ark nexus.org.uk for details. ane Ends Towards est Jesmond ShiremoorNorthumberlandPalmersvilleBenton P Four L LongbentonSouth GosforthIlford RoadW JesmondHaymarketMonumentCentral GatesheadStationGatesheadFelling StadiumHeworthPelaw HebburnJarrow Bede SimonsideTyne DockChichesterSouth Shields South Shields Approx. 2 4 7 8 10 13 14 15 17 19 21 22 25 26 28 30 32 36 39 41 43 45 47 49 journey times Daytime Monday to Saturday Every 12 minutes Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Evenings and Sundays Hour Minutes Hour Minutes Hour Minutes 05 47 59 05 49 05 Every 15 minutes 06 11 23 35 47 59 06 04 19 34 49 06 40 07 11 -

Copy of Draft WMCA Wellbeing Board Outcomes Dashboard (003).Xlsx

WMCA Wellbeing Board Dashboard NB: data flagged with * are population weighted calculations Key: Not compared with benchmark Similar to benchmark All data from Public Health Outcomes Framework Significantly better than benchmark Significantly worse than benchmark Overarching Indicators Compared Compared Latest WMCA Previous Variation (Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Latest WMCA Previous Variation (Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Indicator with Recent trends Indicator with data period Solihull, Walsall, Wolverhampton) data period Solihull, Walsall, Wolverhampton) benchmark benchmark s l d a e v t r a l e t u n Healthy life People with a low c i l a e c expectancy at birth satisfaction score c 59.7 59.3 5.4 5.3 n e e (Male) (%)* b d t i ' f n n a o c C s l d a e v t r a l e t u n Healthy life People with a low c i l a e c expectancy at birth happiness c 60.3 60.9 8.7 8.7 n e e (Female) score(%)* b d t i ' f n n a o c C Gap between Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Disability free life Expectancy – the 18.4 18.4 expectancy (Males) 60.1 n/a ‘Window of Need’ (Male) Gap between Life Expectancy and Disability free life Healthy Life expectancy Expectancy – the 21.8 21.8 59.2 n/a (Females) ‘Window of Need’ (Female) Mental Health CVD/Diabetes Prevention Compared Compared Latest WMCA Previous Variation (Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Latest WMCA Previous Variation (Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Indicator with Recent trends Indicator with data period Solihull, Walsall, Wolverhampton) data period Solihull, Walsall, -

COVENTRY, Connecticut

COVENTRY, Connecticut By Stephanie Summers Some 20 miles east of Hartford lies Coventry, a place Native Americans called Wangumbaug, meaning “crooked pond,” after the shape of the then-300-acre lake within its bounds. The town is probably best known as the birthplace of America’s young Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale, who when captured as a spy against the British and facing the gallows said, “I regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” But its claims to history are much more varied. From the Civil War to the onset of the Great Depression, its strategic waterways fed one of the highest concentrations of mills in New England, with, at the peak, 16 plants built along the Mill Brook. To this day, South Coventry Village retains its authenticity, interrupted by two small, modern-day commercial retail buildings. Used primarily by the Mohegans as a hunting ground with no signs of settlement, the land was given in a will to a group of white settlers in 1675 by Joshua, third son of the sachem Uncas. Sixteen white families, mostly from Hartford and Northampton, Mass., settled the area in 1709. It was named for Coventry, England, in 1711 and incorporated a year later. A church and grist mill were established in short order. In 2010 the U.S. Census estimated Coventry’s population at 12,428 in an area of 38.4 square miles within Tolland County. During the Revolution, the town was of a considerable size, with 2,032 white and 24 black residents. The town divided itself into two societies of sorts, connected to the two early churches. -

Invite Official of the Group You Want to Go

American Celebration of Music in Britain Standard Tour #4 (7 nights/9 days) Day 1 Depart via scheduled air service to London, England Day 2 London (D) Arrive in London Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to the awaiting chartered motorcoach for transfer to the hotel. Enjoy a panoramic tour of London’s highlights including Whitehall and Trafalgar Square with Nelson's Column, and Buckingham Palace, where you might see the Changing of the Guard Drive by Chelsea Embankment and Cheyne Walk home to R. Vaughan Williams Afternoon hotel check-in Evening Welcome Dinner and overnight Established 1,250 years ago, London became an important Roman city. It was resettled by the Saxons in the fifth century, after the end of the Roman occupation. London has been scourged by the plague (1665) and was almost entirely destroyed by the Great Fire (1666). World War II's "Blitzkrieg" tore up the city considerably. She stands today as a monument to perseverance, culture, excitement, history, and greatness Day 3 London (B,D) Breakfast at the hotel Visit the Royal Academy of Music where former students such as Vaughan Williams, Gordon Jacob and Gustav Holst were enrolled Performance as part of the American Celebration of Music in Britain Lunch, on own A guided tour of London includes the residential and shopping districts of Kensington and Knightsbridge. Pass Westminster Abbey, where most English Kings and Queens have been crowned since 1066, and where many are buried. See Piccadilly Circus and pass Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament. Continue along Fleet Street to St.