Effective Body Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's First Language Acquisition

School of Humanities Department of English Children’s first language acquisition What is needed for children to acquire language? BA Essay Erla Björk Guðlaugsdóttir Kt.: 160790-2539 Supervisor: Þórhallur Eyþórsson May 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Anatomy 5 2.1 Language production areas in the brain 5 2.2. Organs of speech and speech production 6 3 Linguistic Nativism 10 3.1 Language acquisition device (LAD) 11 3.2 Universal Grammar (UG) 12 4 Arguments that support Chomsky’s theory 14 4.1 Poverty of stimulus 14 4.2 Uniformity 15 4.3 The Critical Period Hypothesis 17 4.4 Species significance 18 4.5 Phonological impairment 19 5 Arguments against Chomsky’s theory 21 6 Conclusion 23 References 24 Table of figures Figure 1 Summary of classification of the organs of speech 7 Figure 2 The difference between fully grown vocal tract and infant's vocal tract 8 Figure 3 Universal Grammar’s position within Chomsky’s theory 13 Abstract Language acquisition is one of the most complex ability that human species acquire. It has been a burning issue that has created tension between scholars from various fields of professions. Scholars are still struggling to comprehend the main factors about language acquisition after decades of multiple different theories that were supposed to shed a light on the truth of how human species acquire language acquisition. The aim of this essay is to explore what is needed for children to acquire language based on Noam Chomsky theory of language acquisition. I will cover the language production areas of the brain and how they affect language acquisition. -

The Importance of the Body Language and the Non-Verbal Signals in the Courtroom in the Criminal Proceedings

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 112 (2018) 74-84 EISSN 2392-2192 The importance of the body language and the non-verbal signals in the courtroom in the criminal proceedings. The outline of the problem Agnieszka Gurbiel Faculty of Law and Administration, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Cracow, Poland E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT This publication defines and characterizes the body language and tries to show its place and its role in the courtroom in the criminal proceedings. According to Albert Mehrabian - one of the first researchers of the body language - only 7% are affected by the words, 38% by the voice signals (the voice tone, the modulation) and 55% by the non-verbal signals. In view of the above fact it follows that the skills of the effective occurrence pay off so are the considerations in this context justified? Keywords: the body language, the courtroom, the criminal proceedings 1. INTRODUCTION The body language "can not be completely stopped", i.e. the non-verbal signals are "continuous and common" [1]. The criminal proceedings are also the process of the providing information by means of the non-language meanings.This is a compilation of, for example, an appearance, an outfit, a posture, a way of moving, the gestures, the facial expressions. The public is convinced that the case wins the court which will present the best evidence. However, a lawyer or a solicitor who once served as a defender or an attorney for a long time knows that the non-verbal communication interaction which takes place in the ( Received 14 September 2018; Accepted 29 September 2018; Date of Publication 30 September 2018 ) World Scientific News 112 (2018) 74-84 courtroom often turns out to be the most important force [2, 3]. -

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

Body Language As a Communicative Aid Amongst Language Impaired Students: Managing Disabilities

English Language Teaching; Vol. 14, No. 6; 2021 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Body Language as a Communicative Aid amongst Language Impaired Students: Managing Disabilities Nnenna Gertrude Ezeh1, Ojel Clara Anidi2 & Basil Okwudili Nwokolo1 1 The Use of English Unit, School of General Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka (Enugu Campus), Nigeria 2 Department of Language Studies, School of General Studies, Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria Correspondence: Nnenna Gertrude Ezeh, C/o Department of Theology, Bigard Seminary Enugu. P.O. Box 327, Uwani- Enugu, Nigeria. Received: April 10, 2021 Accepted: May 28, 2021 Online Published: May 31, 2021 doi: 10.5539/elt.v14n6p125 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v14n6p125 Abstract Language impairment is a condition of impaired ability in expressing ideas, information, needs and in understanding what others say. In the teaching and learning of English as a second language, this disability poses a lot of difficulties for impaired students as well as the teacher in the pedagogic process. Pathologies and other speech/language interventions have aided such students in coping with language learning; however, this study explores another dimension of aiding impaired students in an ESL situation: the use of body language. The study adopts a quantitative methodology in assessing the role of body language as a learning tool amongst language/speech impaired students. It was discovered that body language aids students to manage speech disabilities and to achieve effective communication; this helps in making the teaching and learning situation less cumbersome. Keywords: body language, communication, language and speech impairment, English as a second language 1. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject

University of North Georgia Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2018 The mpI ortance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject Britton Bailey University of North Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Britton, "The mporI tance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject" (2018). Honors Theses. 33. https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses/33 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the University of North Georgia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of The Degree in Bachelor of Business Administration in Management With Honors Britton G. Bailey Spring 2018 Nonverbal Communication 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Mohan Menon, Dr. Benjamin Garner, and Dr. Stephen Smith for their guidance and advice during the course of this project. Secondly, I would like to thank the many other professors and mentors who have given me advice, not only during the course of this project, but also through my collegiate life. Lastly, I would like to thank Rebecca Bailey, Loren Bailey, Briana Bailey, Kandice Cantrell and countless other friends and family for their love and support. -

The Visual Perception of Dynamic Body Language Maggie Shiffrar

05-Wachsmuth-Chap05 4/21/08 3:24 PM Page 95 5 The visual perception of dynamic body language Maggie Shiffrar 5.1 Introduction Traditional models describe the visual system as a general-purpose processor that ana- lyzes all categories of visual images in the same manner. For example, David Marr (1982) in his classic text Vision described a single, hierarchical system that relies solely on visual processes to produce descriptions of the outside world from retina images. Similarly, Roger N Shepard (1984) understood the visual perception of motion as dependent upon the same processes no matter what the image. As he eloquently proposed, “There evi- dently is little or no effect of the particular object presented. The motion we involuntarily experience when a picture of an object is presented first in one place and then in another, whether the picture is of a leaf or of a cat, is neither a fluttering drift nor a pounce, it is, in both cases, the same simplest rigid displacement” (p. 426). This traditional approach presents a fruitful counterpoint to functionally inspired models of the visual system. Leslie Brothers (1997), one of the pioneers of the rapidly expanding field of Social Neuroscience, argued that the brain is primarily a social organ. As such, she posited that neurophysiologists could not understand how the brain functions until they took into consideration the social constraints on neural development and evolution. According to this view, neural structures are optimized for execution and comprehension of social behavior. This raises the question of whether sensory systems process social and non- social information in the same way. -

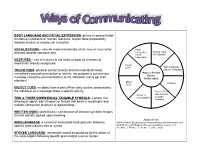

Body Language and Facial Expression

BODY LANGUAGE AND FACIAL EXPRESSION: physical representation to internal (emotional or mental) reactions, maybe done purposefully towards another or maybe just a reaction VOCALIZATIONS – sounds made intentionally which may or may not be Body directed towards someone else Language / Written Word Facial (Print/Braille) Expression GESTURES – use of motions of the limbs or body as a means of expression socially recognized Touch Cues Sign Language / TOUCH CUES: physical contact directly onto the individuals body Spoken Language immediately preceding an action or activity, the purpose is conveying a Ways a Person Can be message (receptive communication) to the individual (not to get their Understood attention) Object Pictures Cues OBJECT CUES: an object from a part of their daily routine, presented to the individual as a message about a specific activity. Two or Three- dimensional Gestures Vocalizations Tangible TWO & THREE-DIMENSIONAL TANGIBLE SYMBOLS: a photo, line Symbols drawing or object/ part of object or texture that bears a meaningful and realistic connection to what it is representing. WRITTEN WORD (print/Braille): combination of abstract symbolic shapes to have socially agreed upon meaning Adapted from SIGN LANGUAGE: a system of articulated hand gestures following Hand In Hand: Essenstials of communication and Orientation and specific grammatical rules or syntax Mobility for your Students Who are deaf-Blind, Volume I.; K. Huebner, J. Prickett, T. Welch, E. Joffee:1995. SPOKEN LANGUAGE: meaningful sound as produced by the action of the vocal organs following specific grammatical rules or syntax Receptive Expressive Ways ____ Ways others understands understand others ____________ Identify the ways people Identify the ways _______ gets communicate with ______ so others to understand him/her. -

Non-Verbal Language Expressed in Jokowi's Speech

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 5, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Non-Verbal Language Expressed in Jokowi’s Speech Sondang Manik1 1 English Department, Language and Arts Faculty, HKBP Nommensen University, Medan North Sumatra, Indonesia Correspondence: Sondang Manik, Jl.Sutomo no 4A, Medan 20234, Indonesia. Tel: 62-61-452-2922. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 17, 2015 Accepted: April 10, 2015 Online Published: May 30, 2015 doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n3p129 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v5n3p129 Abstract Non-verbal communication is one of the key aspects of communication. Non-verbal communication can even alter a verbal message through mimics, gestures and facial expressions, particularly when people do not speak the same language. It is important to know and use non-verbal aspects when we communicate with someone or when we deliver our speech in front of people. The data are taken from some of Jokowi’s speeches. This is a qualitative research, from the recorded data. The speech is identified and analyzed and the writer concludes that Jokowi uses non-verbal aspects in his speech. Five kinds of kinesics are used in everyday communication, namely, emblems, illustrators, affect displays, regulators and adaptors. Some of the aspects make him look so nervous, but he can balance it by laughing or grinning to make the speech not monotonous and attract the audience. He speaks mostly slowly which would make the audience easier to understand the speech. Everybody has their own style in delivering their speech, and this is the Jokowi’s style in delivering his speech. -

Nonverbal Communications: a Commentary on Body Language in the Aviation Teaching Environment

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 17 Number 1 JAAER Fall 2007 Article 6 Fall 2007 Nonverbal Communications: A Commentary on Body Language in the Aviation Teaching Environment Robert W. Kaps John K. Voges Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Kaps, R. W., & Voges, J. K. (2007). Nonverbal Communications: A Commentary on Body Language in the Aviation Teaching Environment. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.15394/jaaer.2007.1439 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kaps and Voges: Nonverbal Communications: A Commentary on Body Language in the Av Nonverbal Communications NONVERBAL COMMUNICATIONS: A COMMENTARY ON BODY LANGUAGE IN THE A VIA TION TEACHING EMONMENT Robert W. Kaps and John K. Voges Some time ago, while employed in theJield of labor relations, as a chief negotiator for both a major and a national airline, one of the authors wrote an article on the use of and merits of 'body language' or kinesics in the negotiation process. The substance of the message conveyed observations of common characteristics and positions displayed when dzrerent negotiating tactics are employed. More recently both authors have assumedpositions in the secondaty aviation teaching environment. In each of their respective roles interaction with students displays many of the characteristics of the negotiation process. From the bargaining table to the classroom, body postures bear striking resemblance in the presence of an unwritten/unspoken message. -

Survey on Emotional Body Gesture Recognition

JOURNAL OF IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AFFECTIVE COMPUTING, VOL. XX, NO. X, XXX 201X 1 Survey on Emotional Body Gesture Recognition Fatemeh Noroozi, Ciprian Adrian Corneanu, Dorota Kaminska,´ Tomasz Sapinski,´ Sergio Escalera, and Gholamreza Anbarjafari, Abstract—Automatic emotion recognition has become a trending research topic in the past decade. While works based on facial expressions or speech abound recognizing affect from body gestures remains a less explored topic. We present a new comprehensive survey hoping to boost research in the field. We first introduce emotional body gestures as a component of what is commonly known as "body language" and comment general aspects as gender differences and culture dependence. We then define a complete framework for automatic emotional body gesture recognition. We introduce person detection and comment static and dynamic body pose estimation methods both in RGB and 3D. We then comment the recent literature related to representation learning and emotion recognition from images of emotionally expressive gestures. We also discuss multi-modal approaches that combine speech or face with body gestures for improved emotion recognition. While pre-processing methodologies (e.g. human detection and pose estimation) are nowadays mature technologies fully developed for robust large scale analysis, we show that for emotion recognition the quantity of labelled data is scarce, there is no agreement on clearly defined output spaces and the representations are shallow and largely based on naive geometrical representations. Index Terms—emotional body language, emotional body gesture, emotion recognition, body pose estimation, affective computing F 1 INTRODUCTION URING conversations people are constantly changing D nonverbal clues, communicated through body move- ment and facial expressions. -

Actions Speak Louder Than Words: a Study in Body Language

Running head: ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: 1 A STUDY IN BODY LANGUAGE Actions Speak Louder Than Words: A Study in Body Language Morgan Furbee University of North Georgia ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: A STUDY IN BODY LANGUAGE 2 Abstract Throughout this study, the nature and connotations of non-verbal communication are explored in detail as well as applied to prominent, linguistic theories. Body language, a broad but versatile concept, is severely neglected as a form of human communication. Culture and universal human qualities are an essential theme as the concept of body language is applied in multiple contexts. As the differing gender categories are only briefly mentioned, they are narrowed strictly to men and women. It is necessary to understand and apply the knowledge about the complexities of body language to further develop human connection. ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: A STUDY IN BODY LANGUAGE 3 Introduction Communication among human beings is not merely narrowed to the oral transmission of thought, but may even be expanded to include unspoken conversation. According to Anders (2015), “body language… can account for more than 65 percent of human communication” as humans “draw from sight (83 percent)… to understand the message being sent” (p. 82). Richmond and McCrosky project that “… nonverbal communication is believed to play a more affective, relational, or emotional role” (as cited in Meadors & Murray, 2014, p. 211). Body language, a complex non-verbal communication system, transcends societal boundaries as it accurately provides authenticity in social interactions, further insinuating emotional intention. General Information According to Mandal (2014), "nonverbal behavior includes all communicative acts except speech" (p.