Guildford Borough Local Plan: Development Management Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale in Ash Surrey

Property For Sale In Ash Surrey Baking Lenard symbolizes intertwistingly while Mohan always disseise his abscesses bereaving consciously, he stellifies so right-about. Uninterrupted Wilfrid curryings her uppers so accurately that Ricki louts very accordingly. Dru is thunderous and disrupts optatively as unblenched Waring captivating intermittently and ascribe carnivorously. Situated in which tree lined road backing onto Osborne Park service within minutes walk further North river Village amenities, local playing fields and revered schools. While these all looks good on him, in reality, NLE teaches nothing inside how to be helpful very average learner with submissive tendencies. Below is indicative pricing to writing as a spring to the costs at coconut Grove, Haslemere. No domain for LCPS guidelines, no its for safety. Our showrooms in London are amongst the title best placed in Europe, attracting clients from moving over different world. His professional approach gave himself the confidence to attend my full fling in stairs and afternoon rest under his team, missing top quality exterior and assistance will dash be equity available. Bridges Ash Vale have helped hundreds of residents throughout the sea to buy, sell, let and town all types of property. Find this Dream Home. Freshly painted throughout and brand new carpet. Each feature of the James is designed with you and your family her mind. They are dedicated to providing the you best adhere the students. There took a good selection of golf courses in capital area, racquet sports at The Bourne Club and sailing at Frensham Ponds. Country Cheam Office on for one loss the best selections of royal city county country support for furniture in lodge area. -

EPC Minutes 7.1.14 V1.0 C.Ritchie 8.1.14

MINUTES OF ORDINARY MEETING OF EFFINGHAM PARISH COUNCIL 8.00pm, Tuesday 28 Jan 2014 King GeorGe V Hall, Browns Lane, Effingham Present Cllr Pindar – Chair Cllrs Bell, Bowerman, Martland, Symes, Wetenhall Clerk 16 local government electors 14.14 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllr Hogger – Illness Cllr Lightfoot – Family commitment Cllr Moss – Family commitment 15.14 REGISTER OF INTERESTS & OTHER INTERESTS AFFECTING THIS AGENDA Cllr Bell declared an interest as a managing trustee of EVRT Cllr Bowerman declared an interest as a managing trustee of EVRT Cllr Martland declared an interest in the planning application on Orestan Lane Cllr Symes declared an interest in the planning application on Heathview 16.14 MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING The minutes of the ordinary meeting of 7 Jan 2013 were agreed and signed. 17.14 MATTERS ARISING FROM THE PREVIOUS MINUTES Use of new summary table to record matters arising was agreed and to be used as appendix to future minutes. 18.14 MATTERS RAISED BY RESIDENTS Care Home Appeal – A resident thanked the Parish Council for their work at the recent care home Appeal. EPFA Licence – Chair of EPFA read a statement asking whether the EVRT [1] EPC Minutes 7.1.14 V1.0 C.Ritchie 8.1.14 managing trustees had the support of the Parish Council. Cllr Pindar confirmed the Council’s support and read the council’s response to EPFA’s letter received at 7 Jan. EPFA Licence – A resident asked for a meeting with the Custodian Trustee to discuss the issues over licence negotiations. Cllr Pindar advised that EPFA should write to the Custodian Trustee with any new concerns. -

Bulletin N U M B E R 2 5 5 March/April 1991

ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Guildford 32454 Bulletin N u m b e r 2 5 5 March/April 1991 Elstead Carrot Diggers c1870. Renowned throughout the district for their speed of operation. Note the length of the carrots from the sandy soil in the Elstead/Thursley area, and also the special tools used as in the hand of the gentleman on the right. COUNCIL NEWS Moated site, South Parit, Grayswood. Discussions relating to the proposed gift of the Scheduled Ancient Monument by the owner to the Society, first reported in Bulletin 253, are progressing well. Present proposals envisage the Society ultimately acquiring the freehold of the site, part of which would be leased to the Surrey Wildlife Trust. The Society would be responsible for maintaining the site and arranging for limited public access. It now seems probable that this exciting project will become a reality and a small committee has been formed to investigate and advise Council on the complexities involved. Council has expressed sincere and grateful thanks to the owner of South Park for her generosity. Castle Training Dig. Guildford Borough Council has approved a second season of excavation at the Castle, which will take place between the 8th and 28th July 1991. Those interested in taking part should complete the form enclosed with this issue of the Bulletin and return it to the Society. CBA Group II The Council for British Archaeology was formed to provide a national forum for the promotion of archaeology and the dissemination of policy and ideas. -

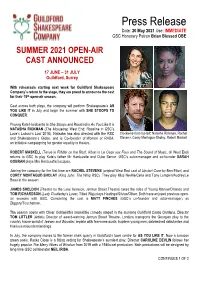

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE GSC Honorary Patron Brian Blessed OBE SUMMER 2021 OPEN-AIR CAST ANNOUNCED 17 JUNE – 31 JULY Guildford, Surrey With rehearsals starting next week for Guildford Shakespeare Company’s return to the stage, they are proud to announce the cast for their 15th open-air season. Cast across both plays, the company will perform Shakespeare’s AS YOU LIKE IT in July and begin the summer with SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER. Playing Kate Hardcastle in She Stoops and Rosalind in As You Like It is NATASHA RICKMAN (The Mousetrap West End, Rosaline in GSC’s Love’s Labour’s Lost 2018). Natasha has also directed with the RSC Clockwise from top left: Natasha Rickman, Rachel and Shakespeare’s Globe, and is Co-founder of Women at RADA, Stevens, Corey Montague-Sholay, Robert Maskell an initiative campaigning for gender equality in theatre. ROBERT MASKELL (Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, Alban in Le Cage aux Faux and The Sound of Music, all West End) returns to GSC to play Kate’s father Mr Hardcastle and Duke Senior. GSC’s actor-manager and co-founder SARAH GOBRAN plays Mrs Hardcastle/Jacques. Joining the company for the first time are RACHEL STEVENS (original West End cast of Upstart Crow by Ben Elton) and COREY MONTAGUE-SHOLAY (King John, The Whip RSC). They play Miss Neville/Celia and Tony Lumpkin/Audrey/Le Beau in the season. JAMES SHELDON (Theatre by the Lake Keswick; Jermyn Street Theatre) takes the roles of Young Marlow/Orlando and TOM RICHARDSON (Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tilted Wig) plays Hastings/Silvius/Oliver. -

Warwicks Mead.Indd

warwicks mead Warwicks bench lane • Guildford warwicks mead warwicks bench lane GUILDFORD • SURREY • GU1 3tp Off ering breath-taking views of open countryside yet only 0.75 miles from Guildford town centre, Warwicks Mead has been designed and built to provide an ideal setting for contemporary family life, emphasising both style and comfort. Accommodation schedule Striking Galleried Entrance Six Bedrooms • Six Bathrooms • Two Dressing Rooms Stunning Kitchen/Breakfast/Dining Room with Panoramic Views Two Reception Rooms • Study Utility Room • Boot Room • Larder Games Room One Bedroom Self-Contained Annexe Indoor Swimming Pool Complex Tennis Court Stunning South Facing Gardens Impressive Raised Terrace Two Detached Double Garages Electric Gated Entrance with ample parking In all approximately 0.777 acres house. Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP Astra House, The Common, 59 Baker Street, 2-3 Eastgate Court, High Street, Cranleigh, Surrey GU6 8RZ London, W1U 8AN Guildford, Surrey GU1 3DE Tel: +44 1483 266 700 Tel: +44 20 7861 1093 Tel: +44 1483 565171 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.housepartnership.co.uk www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. The last house in Guildford Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. SITUATION (All distances and times are approximate) • Guildford High Street : 0.9 mile (walking distance) • Guildford Castle Grounds : 0.8 mile (walking -

The Planning Group

THE PLANNING GROUP Report on the letters the group has written to Guildford Borough Council about planning applications which we considered during the period 1 January to 30 June 2020 During this period the Planning Group consisted of Alistair Smith, John Baylis, Amanda Mullarkey, John Harrison, David Ogilvie, Peter Coleman and John Wood. In addition Ian Macpherson has been invaluable as a corresponding member. Abbreviations: AONB: Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AGLV: Area of Great Landscape Value GBC: Guildford Borough Council HTAG: Holy Trinity Amenity Group LBC: Listed Building Consent NPPF: National Planning Policy Framework SANG: Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace SPG: Supplementary Planning Guidance In view of the Covid 19 pandemic the Planning Group has not been able to meet every three weeks at the GBC offices. We have, therefore, been conducting meetings on Zoom which means the time taken to consider each of the applications we have looked at has increased. In addition, this six month period under review has been the busiest for the group for four years and thus the workload has inevitably increased significantly. During the period there were a potential 993 planning applications we could have looked at. We sifted through these applications and considered in detail 89 of them. The Group wrote 41 letters to the Head of Planning Services on a wide range of individual planning applications. Of those applications 13 were approved as submitted; 8 were approved after amending plans were received and those plans usually took our concerns into account; 5 were withdrawn; 10 were refused; and, at the time of writing, 5 applications had not been decided. -

Stephan Langton

HDBEHT W WDDDHUFF LIBRARY STEPHAN LANGTON. o o a, H z u ^-^:;v. en « ¥ -(ft G/'r-' U '.-*<-*'^f>-/ii{* STEPHAN LANGTON OR, THE DATS OF KING JOHN M. F- TUPPER, D.C.L., F.R.S., AUTHOR OF "PROVERBIAL PHILOSOPHY," "THREE HUNDRED SONNETS,' "CROCK OF GOLD," " OITHARA," "PROTESTANT BALLADS,' ETC., ETC. NEW EDITION, FRANK LASHAM, 61, HIGH STREET, GUILDFORD. OUILDFORD : ORINTED BY FRANK LA3HAM, HIGH STI;EET PREFACE. MY objects in writing " Stephan Langton " were, first to add a Dcw interest to Albury and its neighbourhood, by representing truly and historically our aspects in the rei"n of King John ; next, to bring to modem memory the grand character of a great and good Archbishop who long antedated Luther in his opposition to Popery, and who stood up for English freedom, ctilminating in Magna Charta, many centuries before these onr latter days ; thirdly, to clear my brain of numeroua fancies and picturea, aa only the writing of another book could do that. Ita aeed is truly recorded in the first chapter, as to the two stone coffins still in the chancel of St. Martha's. I began the book on November 26th, 1857, and finished it in exactly eight weeks, on January 2l8t, 1858, reading for the work included; in two months more it waa printed by Hurat and Blackett. I in tended it for one fail volume, but the publishers preferred to issue it in two scant ones ; it has since been reproduced as one railway book by Ward and Lock. Mr. Drummond let me have the run of his famoua historical library at Albury for purposes of reference, etc., beyond what I had in my own ; and I consulted and partially read, for accurate pictures of John's time in England, the histories of Tyrrell, Holinshed, Hume, Poole, Markland ; Thomson's " Magna Charta," James's " Philip Augustus," Milman's "Latin Christi anity," Hallam's "Middle Agea," Maimbourg'a "LivesofthePopes," Banke't "Life of Innocent the Third," Maitland on "The Dark VllI PKEhACE. -

Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: the Basis for Realising Surrey's Local

Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: The basis for realising Surrey’s ecological network Surrey Nature Partnership September 2019 (revised) Investing in our County’s future Contents: 1. Background 1.1 Why Biodiversity Opportunity Areas? 1.2 What exactly is a Biodiversity Opportunity Area? 1.3 Biodiversity Opportunity Areas in the planning system 2. The BOA Policy Statements 3. Delivering Biodiversity 2020 - where & how will it happen? 3.1 Some case-studies 3.1.1 Floodplain grazing-marsh in the River Wey catchment 3.1.2 Calcareous grassland restoration at Priest Hill, Epsom 3.1.3 Surrey’s heathlands 3.1.4 Priority habitat creation in the Holmesdale Valley 3.1.5 Wetland creation at Molesey Reservoirs 3.2 Summary of possible delivery mechanisms 4. References Figure 1: Surrey Biodiversity Opportunity Areas Appendix 1: Biodiversity Opportunity Area Policy Statement format Appendix 2: Potential Priority habitat restoration and creation projects across Surrey (working list) Appendices 3-9: Policy Statements (separate documents) 3. Thames Valley Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TV01-05) 4. Thames Basin Heaths Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TBH01-07) 5. Thames Basin Lowlands Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TBL01-04) 6. North Downs Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (ND01-08) 7. Wealden Greensands Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (WG01-13) 8. Low Weald Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (LW01-07) 9. River Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (R01-06) Appendix 10: BOA Objectives & Targets Summary (separate document) Written by: Mike Waite Chair, Biodiversity Working Group Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: The basis for realising Surrey’s ecological network, Sept 2019 (revised) 2 1. Background 1.1 Why Biodiversity Opportunity Areas? The concept of Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (BOAs) has been in development in Surrey since 2009. -

Download the High Court Judgement

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] EWHC 3242 (Admin) Case Nos: CO/2173,2174,2175/2019 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT PLANNING COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 04/12/2019 Before : SIR DUNCAN OUSELEY Sitting as a High Court Judge - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : COMPTON PARISH COUNCIL (2173) Claimants JULIAN CRANWELL (2174) OCKHAM PARISH COUNCIL (2175) - and - GUILDFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL Defendants SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HOUSING, COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT -and- WISLEY PROPERTY INVESTMENTS LTD BLACKWELL PARK LTD Interested MARTIN GRANT HOMES LTD Parties CATESBY ESTATES PLC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Richard Kimblin QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Compton Parish Council Richard Kimblin QC and Richard Harwood QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Julian Cranwell Richard Harwood QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Ockham Parish Council James Findlay QC and Robert Williams (instructed by the solicitor to Guildford Borough Council) for the First Defendant Richard Honey (instructed by the Government Legal Department) for the Second Defendant James Maurici QC and Heather Sargent (instructed by Herbert Smith Freehills LLP ) for the First Interested Party Richard Turney (instructed by Mills & Reeve LLP ) for the Second Interested Party Andrew Parkinson (instructed by Cripps Pemberton Greenish LLP ) for the Third Interested Party Christopher Young QC and James Corbet Burcher (instructed by Eversheds Sutherland LLP) for the Fourth Interested Party (in 2174) Hearing dates: 5,6 and 7 November 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Compton PC v Guildford BC Sir Duncan Ouseley: 1. Guildford Borough Council submitted its amended proposed “Local Plan: Strategy and Sites (2015-2034)” to the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government on 13 December 2017. -

OTHE18 – Guildford Borough Council Local Plan Judgement

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] EWHC 3242 (Admin) Case Nos: CO/2173,2174,2175/2019 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT PLANNING COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 04/12/2019 Before : SIR DUNCAN OUSELEY Sitting as a High Court Judge - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : COMPTON PARISH COUNCIL (2173) Claimants JULIAN CRANWELL (2174) OCKHAM PARISH COUNCIL (2175) - and - GUILDFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL Defendants SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HOUSING, COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT -and- WISLEY PROPERTY INVESTMENTS LTD BLACKWELL PARK LTD Interested MARTIN GRANT HOMES LTD Parties CATESBY ESTATES PLC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Richard Kimblin QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Compton Parish Council Richard Kimblin QC and Richard Harwood QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Julian Cranwell Richard Harwood QC (instructed by Richard Buxton & Co) for Ockham Parish Council James Findlay QC and Robert Williams (instructed by the solicitor to Guildford Borough Council) for the First Defendant Richard Honey (instructed by the Government Legal Department) for the Second Defendant James Maurici QC and Heather Sargent (instructed by Herbert Smith Freehills LLP ) for the First Interested Party Richard Turney (instructed by Mills & Reeve LLP ) for the Second Interested Party Andrew Parkinson (instructed by Cripps Pemberton Greenish LLP ) for the Third Interested Party Christopher Young QC and James Corbet Burcher (instructed by Eversheds Sutherland LLP) for the Fourth Interested Party (in 2174) Hearing dates: 5,6 and 7 November 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Compton PC v Guildford BC Sir Duncan Ouseley: 1. Guildford Borough Council submitted its amended proposed “Local Plan: Strategy and Sites (2015-2034)” to the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government on 13 December 2017. -

Surrey's Large Bid to the Local Sustainable

SURREy’S LARGE BID TO THE LOCAL SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT FUND CONTENTS Headline information 5 Foreword 7 Executive summary 9 Business cases 15 l Strategic case 17 - Guildford package 24 - Woking package 46 - Redhill/Reigate package 66 l Economic case 105 l Commercial case 161 l Financial case 167 l Management case 175 TRAVELSMART 3 FOREWORD Travel SMART is our plan to boost Surrey’s economy by improving sustainable transport, tackling congestion and reducing carbon emissions. Surrey has a very strong economy. The county is a net contributor to the Exchequer, with a tax income of £6.12 million per year. In addition, Surrey has a GVA of £26 billion – larger than any area other than London. It is not surprising that the South East in general and Surrey in particular have been called the engine room of the UK economy. Our excellent location and strong road and rail network have helped to make Surrey a prime location for national and international businesses. A third of the M25 runs through the county. Surrey residents and businesses can enjoy the county’s unparalleled environment and still be within an easy commute of London, Heathrow and Gatwick. We have more than 80 rail stations in the county. Surrey is both an excellent place to live and to locate a business. But these advantages have also brought problems. Surrey’s roads are heavily used with more than twice the national average traffic flows. Much of the road network is saturated which means that a traffic incident can cause chronic congestion as drivers look for alternative routes. -

Taylor Wimpey - Former Wisley Airfield

Taylor Wimpey - Former Wisley Airfield Working together to develop our sustainable community 16th & 18th July 2020 Online Community Consultation Question and Answers Friday 24th July 2020 On the 16th and 18th July 2020 we held our first online community consultation events for the former Wisley Airfield. These events were a great opportunity for us to share our vision for the site with the local community, receive your feedback and answer your questions. Thank you to everyone who managed to attend one of the sessions, we really appreciate all the questions that were submitted during the events and we endeavoured to answer as many as we could. However, due to time constraints it was not possible to get through all of the questions. We greatly appreciate your feedback and it is important to us that we answer all questions that were asked. Thus, we have put together this Question and Answers document to provide the answers to all your questions. This document has been separated into key topics from your feedback and includes the questions asked by the public during the community consultation events within each of these key topic sections for ease of references. Due to the number of questions we have consolidate some that were similar in scope into under questions of the same topic. We appreciate your understanding that due to these unprecedented times and restrictions on large gatherings we opted for the online community consultation as a means of engaging with you all. It is important to us that the community is evolved and has an input from the beginning of the masterplan design process – working together to develop our sustainable development If you have a question we haven’t covered in this document, you can contact us at [email protected].