National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 by Melissa Armstrong

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 By Melissa Armstrong The ESA SEEDS program had a field trip to Flagstaff, AZ the Havasupai Nation in Western Grand Canyon from May 16 – 20, 2012 as part of the Western Sustainable Communities project with funding from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation. The focus of the field trip was on water sustainability of the Colorado River Basin from a cultural and ecological perspective. The idea for this field trip arose during the Western Regional Leadership Meeting held in Flagstaff in April 2011 as a way to ground our meeting discussions in one of the most iconic places of the Colorado Plateau – the Grand Canyon. SEEDS alumnus Hertha Woody helped ESA connect with the Havasupai Nation; she worked closely with the former Havasupai tribal council during her tenure with Grand Canyon Trust as a tribal liaison. Hertha was instrumental in the planning of this experience for students. In attendance for this field trip were 17 undergraduate and graduate students, 1 alumnus, 1 Chapter advisor, and 2 ESA staff members (21 people total), representing eight Chapter campuses (Dine College Tuba City and Shiprock campuses, ASU, NAU, UNM, SIPI, NMSU, Stanford) – See Appendix A. The students were from a diverse and vibrant background; 42% were Native American, 26% White, 26% Hispanic and 5% Asian. All four of our speakers were Native American. The overall experience was profound given the esteem and generosity of the people who shared their knowledge with our group, the scale of the issues that were raised, the incredibly beautiful setting of Havasu Canyon, and the significant effort that it took to hike to Supai Village and the campgrounds – approximately 30 miles in three days at an elevation change of 1,500 feet each way. -

Grand Canyon National Park

GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK • A R I Z 0 N A • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Grand Canyon [ARIZONA] National Park United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 Rules and Regulations A HE following summary of rules is intended as a guide for all park visitors. You are respectfully requested to facilitate the best in park administration by carefully observing the regulations. Complete regu lations may be seen at the office of the Superintendent. Preservation of 7\[atural Features The first law of a national park is preservation. Disturbance, injury, or destruction in any way of natural features, including trees, flowers, and other vegetation, rocks, and all wildlife, is strictly prohibited. Penalties are imposed for removing fossils and Indian remains, such as arrowheads, etc. Camps Camp or lunch only in designated areas. All rubbish that will burn should be disposed of in camp fires. Garbage cans are provided for noninflammable refuse. Wood and water are provided in all designated camp grounds. Fires Fires are absolutely prohibited except in designated spots. Do not go out of sight of your camp, even for a few moments, without making sure that your fire is either out entirely or being watched. Dogs, Cats, or other Domestic Animals Such animals are prohibited on Government lands within the park except as allowed through permission of the Superintendent, secured from park rangers at entrances. Automobiles The speed limit of 35 miles an hour is rigidly enforced. -

Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory | Pages 164-191

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet section number G, H page 156 V E H I C U L A R B R I D G E S I N A R I Z O N A Geographic Data: State of Arizona Summary of Identification and Evaluation Methods The Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory, which forms the basis for this Multiple Property Documentation Form [MPDF], is a sequel to an earlier study completed in 1987. The original study employed 1945 as a cut-off date. This study inventories and evaluates all of the pre-1964 vehicular bridges and grade separations currently maintained in ADOT’s Structure Inventory and Appraisal [SI&A] listing. It includes all structures of all struc- tural types in current use on the state, county and city road systems. Additionally it includes bridges on selected federal lands (e.g., National Forests, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base) that have been included in the SI&A list. Generally not included are railroad bridges other than highway underpasses; structures maintained by federal agencies (e.g., National Park Service) other than those included in the SI&A; structures in private ownership; and structures that have been dismantled or permanently closed to vehicular traffic. There are exceptions to this, however, and several abandoned and/or privately owned structures of particular impor- tance have been included at the discretion of the consultant. The bridges included in this Inventory have not been evaluated as parts of larger road structures or historic highway districts, although they are clearly integral parts of larger highway resources. -

Linen, Section 2, G to Indians

Arizona, Linen Radio Cards Post Card Collection Section 2—G to Indians-Apache By Al Ring LINEN ERA (1930-1945 (1960?) New American printing processes allowed printing on postcards with a high rag content. This was a marked improvement over the “White Border” postcard. The rag content also gave these postcards a textured “feel”. They were also cheaper to produce and allowed the use of bright dyes for image coloring. They proved to be extremely popular with roadside establishments seeking cheap advertising. Linen postcards document every step along the way of the building of America’s highway infra-structure. Most notable among the early linen publishers was the firm of Curt Teich. The majority of linen postcard production ended around 1939 with the advent of the color “chrome” postcard. However, a few linen firms (mainly southern) published until well into the late 50s. Real photo publishers of black & white images continued to have success. Faster reproducing equipment and lowering costs led to an explosion of real photo mass produced postcards. Once again a war interfered with the postcard industry (WWII). During the war, shortages and a need for military personnel forced many postcard companies to reprint older views WHEN printing material was available. Photos at 43%. Arizona, Linen Index Section 1: A to Z Agua Caliente Roosevelt/Dam/Lake Ajo Route 66 Animals Sabino Canyon Apache Trail Safford Arizona Salt River Ash Fork San Francisco Benson San Xavier Bisbee Scottsdale Canyon De Chelly Sedona/Oak Creek Canyon Canyon Diablo Seligman -

237 265 273 15 Staat Und Verwaltung Las Vegas Bis

STAAT UND VERWALTUNG 15 HIGHLIGHTS 21 ROUTENÜBERSICHT 29 LAS VEGAS BIS ZION NATIONAL PARK 33 A ZION NATIONAL PARK BIS BRYCE CANYON NATIONAL PARK 57 B ÜBER DEN SCENIC BYWAY 12 ZUM CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK 75 C CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK ZUM LAKE POWELL UND MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK 99 D MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK ÜBER MONUMENT VALLEY ZURÜCK ZUM LAKE POWELL 133 E LAKE POWELL ZUM GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 163 F GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK ÜBER DIE ROUTE 66 ZUM LAKE MEAD UND LAS VEGAS 203 G WISSENSWERTES MIT SPRACHHILFE 237 STICHWORTVERZEICHNIS 265 KARTEN 273 AUSZUG AUS NatioNalparkroute uSa – SüdweSt 3. auflage ISBN 978-3-943176-23-0 © 2012 Conbook Medien GmbH. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. NP_USA_Suedwest_Innen_20120314.indd 1 15.03.2012 11:01:04 ɻ INHALTSVERZEICHNIS (,1/(,781* � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 67$$781'9(5:$/781*86$ � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � +,*+/,*+76 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5287(1h%(56,&+7 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Panaca 319 Uvada Springs . 56 Cedar Caliente P Beryl Jct. Newcastle City 143 318 93 M S Cedar A E B=,211$7,21$/3$5.%,6 Ash A 317 Enterprise Old Breaks NM Springs D Acoma Irontown Kanaraville O Ruins W Kolop Canyon %5<&(&$1<211$7,21$/3$5. � � 57 Alamo Elgin 15 V Veyo Zion A Pine L 18 Valley NP Cedar Breaks L Toquerville 9 E E Shivwits Spring- Y G dale R Carp N Hurricane National Monument . . A Santa Clara Rock- R Washington Desert St. George 59ville NWR N O Hildale Red Canyon . M Colorado City R Littlefield 399 Mormon O Mossy Cave . M Valley Wash Mesquite Pipe Spring 168 NM Bunkerville Moapa 15 Wolf Hole Bryce Canyon National Park . -

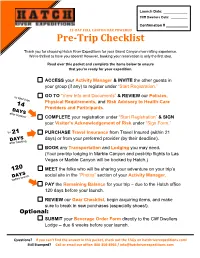

Pre-Trip Checklist

Launch Date: ____________ Cliff Dwellers Date: _________ Confirmation # ___________ 12-DAY FULL CANYON OAR POWERED Pre-Trip Checklist Thank you for choosing Hatch River Expeditions for your Grand Canyon river rafting experience. We’re thrilled to have you aboard! However, booking your reservation is only the first step. Read over this packet and complete the items below to ensure that you’re ready for your expedition. ACCESS your Activity Manager & INVITE the other guests in your group (if any) to register under “Start Registration.” GO TO “View Info and Documents” & REVIEW our Policies, Physical Requirements, and Risk Advisory to Health-Care Providers and Participants. COMPLETE your registration under “Start Registration” & SIGN your Visitor’s Acknowledgement of Risk under “Sign Form.” PURCHASE Travel Insurance from Travel Insured (within 21 days) or from your preferred provider (by their deadline). BOOK any Transportation and Lodging you may need. (Your pre-trip lodging in Marble Canyon and post-trip flights to Las Vegas or Marble Canyon will be booked by Hatch.) MEET the folks who will be sharing your adventure on your trip’s social site in the “Photos” section of your Activity Manager. PAY the Remaining Balance for your trip – due to the Hatch office 120 days before your launch. REVIEW our Gear Checklist, begin acquiring items, and make sure to break in new purchases (especially shoes!). Optional: SUBMIT your Beverage Order Form directly to the Cliff Dwellers Lodge – due 6 weeks before your launch. Questions? If you can’t find the answer in this packet, check out the FAQs on hatchriverexpeditions.com! Still Stumped? Call or email our office: 800-856-8966 / [email protected] 12 DAY FULL CANYON OAR POWERED Policies Registration Forms Cancellations You must complete a Registration Form for every guest If you must cancel your reservation more than 120 on your reservation within 14 days of making your days before your trip, you must notify us in writing. -

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004 Jeff and I left the Fruita-4 place at about 8 AM and tooled west on I-70 to exit 202 at UT-128 near Cisco, Utah. We drove south on UT-128 through the Colorado River canyons to US-191, just north of Moab. We turned south and drove through Moab on US-191 to US-163, past Bluff, Utah. US-163 veers southwest through Monument Valley into Arizona and the little town of Keyenta. At Keyenta we took US-160 west to US-89, then south to AZ-64. We drove west past the fairly spectacular canyons of the Little Colorado River and into the east entrance to Grand Canyon National Park. Jeff had a Parks Pass so we saved $20 and got in for free. Entry included the park information paper, The Guide, which included a park map that was especially detailed around the main tourist center: Grand Canyon Village. Near the village was our pre-hike destination, the Backcountry Office. We stopped at the office and got an update on the required shuttle to the trailhead. We read in The Guide that mule rides into the canyon would not begin until May 23, after we were done with our hike. Satisfied that we had the situation under control we skeedaddled on outta there on US-180, south to I-40 and Williams, Arizona. Jeff had tried his cell phone quite a few times on the trip from Fruita, but no signal. Finally the signal was strong enough in Williams. Jeff noted that Kent had called and returned the call. -

Introduction to Backcountry Hiking

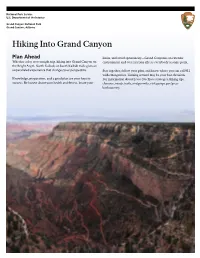

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Hiking Into Grand Canyon Plan Ahead limits, and avoid spontaneity—Grand Canyon is an extreme Whether a day or overnight trip, hiking into Grand Canyon on environment and overexertion affects everybody at some point. the Bright Angel, North Kaibab, or South Kaibab trails gives an unparalleled experience that changes your perspective. Stay together, follow your plan, and know where you can call 911 with emergencies. Turning around may be your best decision. Knowledge, preparation, and a good plan are your keys to For information about Leave No Trace strategies, hiking tips, success. Be honest about your health and fitness, know your closures, roads, trails, and permits, visit go.nps.gov/grca- backcountry. Warning While Hiking BALANCE FOOD AND WATER Hiking to the river and back in one • Do not force fluids. Drink water when day is not recommended due to you are thirsty, and stop when you are long distance, extreme temperature quenched. Over-hydration may lead to a changes, and an approximately 5,000- life-threatening electrolyte disorder called foot (1,500 m) elevation change each hyponatremia. way. RESTORE YOUR ENERGY If you think you have the fitness and • Eat double your normal intake of expertise to attempt this extremely carbohydrates and salty foods. Calories strenuous hike, please seek the advice play an important role in regulating body of a park ranger at the Backcountry temperature, and hiking suppresses your Information Center. appetite. TAKE CARE OF YOUR BODY Know how to rescue yourself. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

North Kaibab Trail

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona North Kaibab Trail The North Kaibab Trail is the least visited but most difficult of the three maintained trails at Grand Canyon National Park. Almost a thousand feet higher at the trailhead than South Rim trails, hikers on the North Kaibab Trail pass through every ecosystem to be found between Canada and Mexico. At the rim, hikers will glimpse the vast maw of Bright Angel Canyon through fir trees and aspen, ferns and wildflowers. The trail as it descends through the Redwall Limestone is blasted directly into the cliff, "literally hewn from solid rock in half-tunnel sections." Farther down, the ecology progresses so that hikers look up at the surrounding canyon walls through a blend of riparian and desert vegetation. Along the way, Roaring Springs and Ribbon Falls both offer rewarding side trips that are wonderfully juxtaposed to the often hot conditions of the main trail. Built throughout the 1920s to match the quality and grade of the South Kaibab Trail, the present-day North Kaibab Trail replaced an older route infamous for crossing Bright Angel Creek 94 times (the present-day trail crosses only 6 times). Even though it is masterfully constructed and is a maintained trail, don't be deceived by the apparent ease and convenience of hiking it; from beginning to end, the North Kaibab Trail has its challenges. Locations/Elevations Mileages North Kaibab trailhead (8241 ft / 2512 m) to Supai Tunnel (6800 ft / 2073 m): 1.7 mi ( 2.5 km) Supai -

S 2

13 00 +J ^ .S 2 *c3 -3 - '£ w 2 S PQ <$ H Grand Canyon hiking is the reverse of moun tain climbing. First the descent, then the climb out, when one is tired — (exhausted). When you hike down into Grand Canyon you are entering a desert area where shade and water are scarce and where summer temperatures often exceed 41 C (105 F) and drop below freezing in winter. PLAN AHEAD! Allow at least 3 km (2 mi) per hour to descend and 21/2 km MVimi) per hour to ascend. ARE WE THERE YET ? ? DISTANCES: FROM BRIGHT ANGEL TRAILHEAD TO: Indian Gardens 7.4 km (4.6 mi) Colorado River 12.5 km (7.8 mi) Bright Angel Camp 14.9 km (9.3 mi) FROM SOUTH KAIBAB TRAILHEAD TO: Cedar Ridge 2.4 km (1.5 mi) Tonto Trail Junct. 7.1 km (4.4 mi) Bright Angel Camp 10.8 km (6.4 mi) FROM BRIGHT ANGEL CAMP AT RIVER TO: Ribbon Falls 9.3 km ( 5.8 mi) Cottonwood 11.7 km ( 7.3 mi) Roaring Springs 15.3 km ( 9.5 mi) North KaibabTrailhead 22.8 km (14.2 mi) FROM INDIAN GARDENS CAMP TO: Bright Angel Camp 7.5 km (4.7 mi) Plateau Point 2.4 km (1.5 mi) S. Kaibab Trail 6.6 km (4.1 mi) Junct. via Tonto Trail ELEVATIONS Bright Angel Lodge, South Rim 2091M (6860 ft) Yaki Point 2213M (7260 ft) Indian Gardens 1160M (3800 ft) Plateau Point 1150M (3760 ft) Bright Angel Camp 730M (2400 ft) Cottonwood 1220M (4000 ft) Roaring Springs 1580M (5200 ft) N.