Chewton Mendip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the Mendip Hills AONB

MENDIP TIMES MENDIP HILLS AONB Discover the Mendip Hills AONB The Pound, Rodney Stoke Young Rangers During April, the parish council have been restoring the lime archery session with mortared walls of The Pound. The area was originally where Wells City Archers stray animals used to be held until owners claimed them. It is now a popular amenity area for residents and visitors and acts as a memorial of Rodney Stoke as a thankful village. The walling work has been led by Woodlouse Conservation training local volunteers. The AONB Sustainable Development Fund provided a grant for the work. Become a Mendip Hills AONB Young Ranger! We are recruiting for the new two-year programme that will begin in September 2011 and run until July 2013. There are places for 15 young people aged 11 – 15 who live in or near the AONB. Activities take place one Saturday per month except August and December with an overnight camp each year. Activities include first aid and navigation, star gazing, practical tasks and learning about the AONB. Mendip Rocks August 25th – October 1st Further information and the Following on from the Mendip Hills AONB Annual Forum application form will be available 2009 that discussed bidding for European Geopark status for the on the website in May. City of Mendip Hills, this is the first of what is hoped will be an annual Wells has sponsored a place this event as part of a wider programme to encourage interest and year and Cheddar, Compton understanding of the area’s unique geodiversity. Martin, Rodney Stoke, Ubley, Somerset Earth Science Centre are holding several events Shipham and Churchill parish including activities at Wells Museum and visit to a Silurian councils have provided funding volcano, there are also visits to Westbury Quarry, Avon Wildlife towards this scheme. -

Sat 14Th and Sun 15Th October 2017 10Am To

CHEW VALLEY BLAGDON BLAGDON AND RICKFORD RISE, BURRINGTON VENUE ADDRESSES www.chewvalleyartstrail.co.uk To Bishopsworth & Bristol Sarah Jarrett-Kerr Venue 24 Venue 11 - The Pelican Inn, 10 South Margaret Anstee Venue 23 Dundry Paintings, mixed media and prints Book-binding Parade, Chew Magna. BS40 8SL North Somerset T: 01761 462529 T: 01761 462543 Venue 12 - Bridge House, Streamside, E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Chew Magna. BS40 8RQ Felton Winford Heights 2 The art of seeing means everything. The wonderful heft and feel of leather To A37 119 7 Landscape and nature, my inspiration. bound books and journals. Venue 13 - Longchalks, The Chalks, Bristol International Pensford B3130 3 & Keynsham Chew Magna. BS40 8SN Airport 149Winford Upton Lane Suzanne Bowerman Venue 23 Jeff Martin Venue 25 Sat 14th and Sun 15th Venue 14 - Chew Magna Baptist Chapel, Norton Hawkfield Belluton Paintings Watercolour painting A38 T: 01761 462809 Tunbridge Road, Chew Magna. BS40 8SP B3130 October 2017 T: 0739 9457211 Winford Road B3130 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Venue 15 - Stanton Drew Parish Hall, Sandy 192 13 1S95tanton Drew Colourful, atmospheric paintings in a To Weston-Super-Mare 17 An eclectic mix of subjects - landscapes, 5 11 16 10am to 6pm variety of subjects and mediums. Lane, Stanton Drew. BS39 4EL or Motorway South West 194 seascapes, butterflies, birds and still life. Regil Chew Magna CV School Venue 16 - The Druid's Arms, 10 Bromley Stanton Wick Chris Burton Venue 23 Upper Strode Chew Stoke 8 VENUE ADDRESSES Road, Stanton Drew. BS39 4EJ 199 Paintings 6 Denny Lane To Bath T: 07721 336107 Venue 1 - Ivy Cottage, Venue 17 - Alma House, Stanton Drew, (near A368 E: [email protected] 50A Stanshalls Lane, Felton. -

Mendip Hills AONB Partnership Committee Draft Minutes of the Meeting at Westbury-Sub-Mendip Village Hall 21St November 2019 Present

Mendip Hills AONB Partnership Committee Draft Minutes of the meeting at Westbury-sub-Mendip Village Hall 21st November 2019 Present: Partnership Committee Cllr Nigel Taylor (Chair) Somerset County Council Di Sheppard Bath & North East Somerset Council Officer Jim Hardcastle AONB Manager Tom Lane Natural England Richard Frost Mendip Society David Julian CPRE Rachel Thompson MBE The Trails Trust Julie Cooper Sedgemoor District Council Officer Pippa Rayner Somerset Wildlife Trust Cllr Karin Haverson North Somerset Council Cllr Elizabeth Scott Sedgemoor District Council Cllr Mike Adams North Somerset Parish Councils Representative Cllr David Wood Bath & North East Somerset Other attendees Kelly Davies AONB Volunteer Ranger Mick Fletcher AONB Volunteer Ranger Cat Lodge Senior Archaeologist, North Somerset Council Jo Lewis Natural England Anne Halpin Somerset Wildlife Trust Simon Clarke Somerset Wildlife Trust Cindy Carter AONB Landscape Planning Officer Tim Haselden AONB Project Development Officer Lauren Holt AONB Ranger Volunteer Coordinator Sarah Catling AONB Support & Communications Officer Apologies Chris Lewis CPRE Ian Clemmett National Trust Joe McSorley Avon Wildlife Trust Cllr Edric Hobbs Mendip District Council Cllr Roger Dollins Somerset Parish Councils Representative Cllr James Tonkin North Somerset Council Steve Dury Somerset County Council Officer John Flannigan North Somerset Council Officer Rachel Tadman Mendip District Council Officer Andy Wear National Farmers Union 1 Summary of Actions Item Item Notes Action 1 Declaration of No declarations. Interest 2 Notes of Apologies as stated. Previous Meeting Key action from previous minutes; to invite Richard Penny from Natural England to update on the new farm payment system, given the current situation and with RP leaving this was changed to invite reps from the Somerset Wildlife Trust. -

The Boundary Committee for England Further Electoral

SHEET 3, MAP 3 Mendip District. Proposed wards and parish wards in Wells and St Cuthbert Out CHEWTON MENDIP CP Big Stoke Westbury Beacon Reservoir CHEWTON MENDIP AND STON EASTON WARD Def De RODNEY STOKE CP (covered) f Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Grid intervalBroadmead 1km Quarry KEY PRIDDY CP PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY Def PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH OTHER BOUNDARIES Priddy Road Farm PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY WELLS CENTRAL WARD PROPOSED WARD NAME E WELLS CP PARISH NAME V O R WELLS CENTRAL PARISH WARD PARISH WARD NAME D G IN T L E O P L Und D B R I Und Und S T O L "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission R O with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. A D Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. f e D LicenceBroadway Number: Hill GD03114G" D UR D SD ef ON DR OV d d E n n (Tr U U a ck) RODNEY AND WESTBURY WARD Def Perch Hill Sch WESTBURY CP D e D f Westbury-sub-Mendip PW e f Ebbor Gorge National Nature Reserve f e D Rookham Def Sewage Works ST CUTHBERT OUT EAST PARISH WARD D e f Easton ST CUTHBERT OUT NORTH PARISH WARD f ST CUTHBERT OUT NORTH WARD e D PW Church Wookey Lower Milton Hole Upper Milton U n d Milton Quarry (disused) ROVE U U MOOR D n nd 9 KNOWLE d A 3 Knowle Bridge U n Def d f e D D f ef e D Def D St Cuthbert's ism Paper Works ant le D d e Rai f D lw e a 9 f y d n 3 U 1 3 B Works d n U E N f e A D L 'S R E E N K D A ef L WELLS ST THOMAS' -

Notice of Poll

SOMERSET COUNTY COUNCIL ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR FROME EAST DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of A COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the FROME EAST DIVISION will be held on THURSDAY 4 MAY 2017, between the hours of 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM 2. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidates nomination papers are as follows: Name of Candidate Address Description Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper Eve 9 Whitestone Road The Conservative J M Harris M Bristow BERRY Frome Party Candidate B Harris P Bristow Somerset Kelvin Lum V Starr BA11 2DN Jennifer J Lum S L Pomeroy J Bristow J A Bowers Martin John Briars Green Party G Collinson Andrew J Carpenter DIMERY Innox Hill K Harley R Waller Frome J White T Waller Somerset M Wride M E Phillips BA11 2LW E Carpenter J Thomas Alvin John 1 Hillside House Liberal Democrats A Eyers C E Potter HORSFALL Keyford K M P Rhodes A Boyden Frome Deborah J Webster S Hillman BA11 1LB J P Grylls T Eames A J Shingler J Lewis David Alan 35 Alexandra Road Labour Party William Lowe Barry Cooper OAKENSEN Frome Jean Lowe R Burnett Somerset M R Cox Karen Burnett BA11 1LX K A Cooper A R Howard S Norwood J Singer 3. The situation of the Polling Stations for the above election and the Local Government electors entitled to vote are as follows: Description of Persons entitled to Vote Situation of Polling Stations Polling Station No Local Government Electors whose names appear on the Register of Electors for the said Electoral Area for the current year. -

The Long Barrows and Long Mounds of West Mendip

Proc. Univ. Bristol Spelaeol. Soc., 2008, 24 (3), 187-206 THE LONG BARROWS AND LONG MOUNDS OF WEST MENDIP by JODIE LEWIS ABSTRACT This article considers the evidence for Early Neolithic long barrow construction on the West Mendip plateau, Somerset. It highlights the difficulties in assigning long mounds a classification on surface evidence alone and discusses a range of earthworks which have been confused with long barrows. Eight possible long barrows are identified and their individual and group characteristics are explored and compared with national trends. Gaps in the local distribution of these monuments are assessed and it is suggested that areas of absence might have been occupied by woodland during the Neolithic. The relationship between long barrows and later round barrows is also considered. INTRODUCTION Long barrows are amongst the earliest monuments to have been built in the Neolithic period. In Southern Britain they take two forms: non-megalithic (or “earthen”) long barrows and megalithic barrows, mostly belonging to the Cotswold-Severn tradition. Despite these differences in architectural construction, the long mounds are of the same, early 4th millennium BC, date and had a similar purpose. The chambers of the long mounds were used for the deposition of the human dead and the monuments themselves appear to have acted as a focus for ritual activities and religious observations by the living. Some long barrows show evidence of fire lighting, feasting and deposition in the forecourts and ditches of the monuments, and alignment upon solstice events has also been noted. A local example of this can be observed at Stoney Littleton, near Bath, where the entrance and passage of this chambered long barrow are aligned upon the midwinter sunrise1. -

Mendip Hills AONB Survey

Mendip Hills An Archaeological Survey of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty by Peter Ellis ENGLISH HERITAGE Contents List of figures Introduction and Acknowledgements ...................................................1 Project Summary...................................................................................2 Table 1: New sites located during the present survey..................3 Thematic Report Introduction ................................................................................10 Hunting and Gathering...............................................................10 Ritual and Burial ........................................................................12 Settlement...................................................................................18 Farming ......................................................................................28 Mining ........................................................................................32 Communications.........................................................................36 Political Geography....................................................................37 Table 2: Round barrow groups...................................................40 Table 3: Barrow excavations......................................................40 Table 4: Cave sites with Mesolithic and later finds ...................41 A Case Study of the Wills, Waldegrave and Tudway Quilter Estates Introduction ................................................................................42 -

Obituary: Ann Heeley 1940–2017

SOMERSET ARCHAEOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY, 2017 OBITUARY: ANN HEELEY 1940–2017 Ann Heeley, who made a huge contribution to the presented by Fred Housego. study of local and social history in Somerset for In 1975 Ann volunteered to help the newly over 40 years, died suddenly and unexpectedly on developing Somerset Rural Life Museum (SRLM) 8 March. It seems fitting that on the day before in Glastonbury, her youngest child now in pre- she died, Ann was doing what she most enjoyed: school. Demonstrating her growing enthusiasm for interviewing and recording Somerset farmers. local and rural history, Ann was asked to gather information for the forthcoming exhibitions by interviewing strawberry growers in Cheddar (using a cumbersome reel to reel tape recorder). Returning a few days later, elated by her conversations, she launched into a lifetime of commitment to what has become the ‘Somerset Voices Oral History Archive’. Ann’s extraordinary dedication to oral history grew from her delight in meeting people –especially those who shared her love of the countryside, farming and rural life. Over 40 years she accomplished more than 700 recorded interviews, ranging from farmers and their families to those working in the many distinctive Somerset crafts and industries. Fascinating accounts of working and social life reflect a time of enormous change, Ann Heeley interviewing Walter Baber with memories going back well into the Victorian of Chewton Mendip in 1981 period and other more recent interviews recording life in the 21st century. The archive is one of the She was born Ann Williamson in Warrington, UK’s most significant collections of its kind and Cheshire, the eldest of four children. -

Statutory Consultees and Agencies

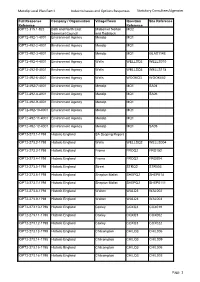

Mendip Local Plan Part II Index to Issues and Options Responses Statutory Consultees/Agencies Full Response Company / Organisation Village/Town Question Site Reference Reference Reference IOPT2-315.1-823 Bath and North East Midsomer Norton MQ2 Somerset Council and Radstock IOPT2-492-1-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-2-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-3-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 GLAS114E IOPT2-492-4-4001 Environment Agency Wells WELLSQ3 WELLS010 IOPT2-492-5-4001 Environment Agency Wells WELLSQ3 WELLS118 IOPT2-492-6-4001 Environment Agency Wells WOOKQ3 WOOK002 IOPT2-492-7-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA04 IOPT2-492-8-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA06 IOPT2-492-9-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-10-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-11-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-12-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA05 IOPT2-273.1-1798 Historic England SA Scoping Report IOPT2-273.2-1798 Historic England Wells WELLSQ2 WELLS004 IOPT2-273.3-1798 Historic England Frome FROQ2 FRO152 IOPT2-273.4-1798 Historic England Frome FROQ2 FRO004 IOPT2-273.5-1798 Historic England Street STRQ2 STR003 IOPT2-273.6-1798 Historic England Shepton Mallet SHEPQ2 SHEP014 IOPT2-273.7-1798 Historic England Shepton Mallet SHEPQ2 SHEP0111 IOPT2-273.8-1798 Historic England Walton WALQ3 WAL002 IOPT2-273.9-1798 Historic England Walton WALQ3 WAL003 IOPT2-273.10-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 COX019 IOPT2-273.11-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 COX002 IOPT2-273.12-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 -

Ashwick, Oakhill & Binegar News

The Beacon Ashwick, Oakhill & Binegar News JULY 2021 Cover photo: © Richard Venn Church Services – July 2021 Sunday, 4th July 10am Communion St. James, Ashwick Sunday, 11th July 10am Family Worship All Saints, Oakhill with baptism Sunday, 18th July 10am Communion St. James, Ashwick Sunday, 25th July 10am Communion Holy Trinity, Binegar 4pm 4th@4 Outdoors Simbriss Farm, Ashwick Would you like to support the churches in our parish? Please scan the QR code and make a donation online. Thank you. Please visit www.beacontrinity.church or: Follow us on Instagram! facebook.com/beacontrinity instagram.com/beacontrinity View from the Hill July 15th is St. Swithin’s Day, so Encyclopaedia Britannica says! St. Swithin’s Day, (July 15), a day on which, according to folklore, the weather for a subsequent period is dictated. In popular belief, if it rains on St. Swithin’s Day, it will rain for 40 days, but if it is fair, 40 days of fair weather will follow. St. Swithin was Bishop of Winchester from 852 to 862. At his request he was buried in the churchyard, where rain and the steps of passers by might fall on his grave. According to legend, after his body was moved inside the cathedral on July 15, 971, a great storm ensued. The first textual evidence for the weather prophecy appears to have come from a 13th- or 14th-century entry in a manuscript at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. You can find lots more history about him, but he is perhaps one of the more commonly heard of saints, even if its only the legend about the weather. -

GEOMORPHOLOGY and HYDROLOGY of the CENTRAL MENDIPS Steady Gradient of About I in 90 to Crook Peak (628 Ft.) and with Only Slightly Less Regularity to 400 Ft

Geomorphology and Hydrology or the Central Mendips. Proc. Univ. Brist. Spe1. Soc., 1969, 12 (I), 63-74. Jubilee Contribution University ofBristol Spel.eological Society Geomorphologyand Hydrology of the Central Mendips By D. T. DONOVAN, D.Se. Only in the last few years has the Society carried out and published work on cave geomorphology and hydrology. This article attempts to relate this work to the geomorphological problems of the Mendip Hills. These will be reviewed first. The first question which must be settled is the degree to which the relief of the Palreozoic rocks is an exhumed relief dating from Triassic times, revealed by the removal ofMesozoic rocks. Some authors, perhaps in spired by Lloyd Morgan (Morgan 1888 p. 250; Morgan & Reynolds 1909, p. 24), have thought Triassic erosion an important factor in determining details ofpresent relief. While the broad reliefofnorth Somerset certainly reflects that of the late Trias, when the Coal Measures vales between the Carboniferous Limestone uplands had already been eroded to their present level or lower, I question whether the relationship holds in any detail. Some of the marginal slopes of Mendip may be little more than old Carboniferous Limestone slopes exhumed by removal of Trias, but along the southern limit of the Mendips the characteristic steep, regular marginal slope is, in fact, largely cut in the Triassic Dolomitic Conglo merate which has an exceedingly irregular contact with the Carboniferous Limestone. Similarly, the summit plateau cuts indiscriminately across Carboniferous and Triassic. All the anticlinal cores were exposed by erosion in Triassic times, but except west of Rowberrow, where the Old Red Sandstone core ofthe Blackdown anticline was already eroded down to a low level in the Trias, I conclude, with Ford and Stanton (1969) that the Triassic landscape is unimportant in controlling present relief. -

2017 Projections for Somerset by Current Parish and Electoral Divisions

Electoral data Check your data 2011 2017 Using this sheet: Number of councillors: 58 58 Fill in the cells for each polling district. Please make sure that the names of each parish, parish ward and district Overall electorate: 418,813 447,542 ward are correct and consistant. Check your data in the cells to the right. Average electorate per cllr: 7,221 7,716 Scroll right to see the second table Scroll left to see the first table Is this polling district What is the Is this polling district contained in Is this polling district What is the What is the Fill in the number Is there any other description contained in a group of What District ward is this polling What county Electoral Division These cells will show you the electorate and variance. They change polling district a parish? If not, leave this cell contained in a parish ward? current predicted Fill in the name of each ward once of councillors per you use for this area? parishes with a joint parish district in? is this polling district in? depending what you enter in the table to the left. code? blank. If not, leave this cell blank. electorate? electorate? ward council? If not, leave this District Council Polling Grouped parish Existing Electoral Electorate Electorate Number of Electorate Electorate Description of area Parish Parish ward District Ward Name of Electoral Division Variance 2011 Variance 2017 area district council Division 2011 2017 cllrs per ward 2011 2017 EX1 Example 1 Little Example Little and Even Littler Example Example 480 502 Dulverton & Exmoor 1 5,966 -17% 6,124