Appendix 3 Lichfield HECZ Assessments Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

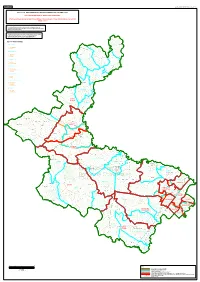

B H I J Q L K M O N a E C D G

SHEET 1, MAP 1 East_Staffordshire:Sheet 1 :Map 1: iteration 1_D THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EAST STAFFORDSHIRE Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of East Staffordshire June 2020 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. KEY TO PARISH WARDS BURTON CP A ST PETER'S OKEOVER CP B TOWN OUTWOODS CP C CENTRAL D NORTH E SOUTH STANTON CP SHOBNALL CP WOOTTON CP F CANAL G OAKS WOOD MAYFIELD CP STAPENHILL CP RAMSHORN CP H ST PETER'S I STANTON ROAD J VILLAGE UTTOXETER CP ELLASTONE CP K HEATH L TOWN UTTOXETER RURAL CP M BRAMSHALL N LOXLEY O STRAMSHALL WINSHILL CP DENSTONE CP P VILLAGE Q WATERLOO ABBEY & WEAVER CROXDEN CP ROCESTER CP O UTTOXETER NORTH LEIGH CP K M UTTOXETER RURAL CP UTTOXETER CP L UTTOXETER SOUTH N MARCHINGTON CP KINGSTONE CP DRAYCOTT IN THE CLAY CP CROWN TUTBURY CP ROLLESTON ON DOVE CP HANBURY CP DOVE STRETTON CP NEWBOROUGH CP STRETTON C D BAGOTS OUTWOODS CP ABBOTS ANSLOW CP HORNINGLOW BROMLEY CP & OUTWOODS BLITHFIELD CP HORNINGLOW B AND ETON CP E BURTON & ETON G F BURTON CP P SHOBNALL WINSHILL WINSHILL CP SHOBNALL CP HOAR CROSS CP TATENHILL CP Q A BRIZLINCOTE BRANSTON CP ANGLESEY BRIZLINCOTE CP CP BRANSTON & ANGLESEY NEEDWOOD H STAPENHILL I STAPENHILL CP J DUNSTALL CP YOXALL CP BARTON & YOXALL BARTON-UNDER-NEEDWOOD CP WYCHNOR CP 01 2 4 KEY BOROUGH COUNCIL BOUNDARY Kilometres PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY 1 cm = 0.3819 km PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY BAGOTS PROPOSED WARD NAME WINSHILL CP PARISH NAME. -

Yoxall to the National Memorial Arboretum

This leaflet can be used in conjunction with The National Forest Way OS Explorer 245 (The National Forest) The National Forest Way takes walkers on a 75-mile journey through a transforming Stage 12: landscape, from the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire to Beacon Hill Country Park in Leicestershire. Yoxall to the On the way, you will discover the area’s evolution from a rural landscape, through Start National Memorial industrialisation and its decline, to the modern-day creation of a new forest, where 21st-century life is threaded through a mosaic End Arboretum of green spaces and settlements. Length: 5 miles / 8 kilometres The trail leads through young and ancient woodlands, market towns and the industrial heritage of this changing landscape. Burton upon Trent About this stage Swadlincote Start: Yoxall (DE13 8NQ) Ashby End: National Memorial Arboretum (DE13 7AR) de la Zouch Coalville On this stage, the route is never far from the River Swarbourn. You will enjoy views over the Trent Valley towards Lichfield with its prominent cathedral, passing through young woodlands and open river meadows. Visit the villages of Yoxall and Alrewas and the National Memorial Arboretum, a place of reflection and The National Forest Way was created by a remembrance. partnership of the National Forest Company, Derbyshire County Council, Leicestershire County Council and Staffordshire County The National Forest Company Council, with the generous Bath Yard, Moira, Swadlincote, support of Fisher German. Derbyshire DE12 6BA Telephone: 01283 551211 Enquiries: www.nationalforestway.co.uk/contact Website: www.nationalforest.org To find out more, visit: Photos: Jacqui Rock, Christopher Beech and www.nationalforestway.co.uk Martin Vaughan Maps reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. -

Premises Licence List

Premises Licence List PL0002 Drink Zone Plus Premises Address: 16 Market Place Licence Holder: Jasvinder CHAHAL Uttoxeter 9 Bramblewick Drive Staffordshire Littleover ST14 8HP Derby Derbyshire DE23 3YG PL0003 Capital Restaurant Premises Address: 62 Bridge Street Licence Holder: Bo QI Uttoxeter 87 Tumbler Grove Staffordshire Wolverhampton ST14 8AP West Midlands WV10 0AW PL0004 The Cross Keys Premises Address: Burton Street Licence Holder: Wendy Frances BROWN Tutbury The Cross Keys, 46 Burton Street Burton upon Trent Tutbury Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE13 9NR Staffordshire DE13 9NR PL0005 Water Bridge Premises Address: Derby Road Licence Holder: WHITBREAD GROUP PLC Uttoxeter Whitbread Court, Houghton Hall Business Staffordshire Porz Avenue ST14 5AA Dunstable Bedfordshire LU5 5XE PL0008 Kajal's Off Licence Ltd Premises Address: 79 Hunter Street Licence Holder: Rajeevan SELVARAJAH Burton upon Trent 45 Dallow Crescent Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE14 2SR Stafffordshire DE14 2PN PL0009 Manor Golf Club LTD Premises Address: Leese Hill Licence Holder: MANOR GOLF CLUB LTD Kingstone Manor Golf Club Uttoxeter Leese Hill, Kingstone Staffordshire Uttoxeter ST14 8QT Staffordshire ST14 8QT PL0010 The Post Office Premises Address: New Row Licence Holder: Sarah POWLSON Draycott-in-the-Clay The Post Office Ashbourne New Row Derbyshire Draycott In The Clay DE6 5GZ Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 5GZ 26 Jan 2021 at 15:57 Printed by LalPac Page 1 Premises Licence List PL0011 Marks and Spencer plc Premises Address: 2/6 St Modwens Walk Licence Holder: MARKS -

Lichfield City Conservation Area Appraisal

1 Introduction 3 2 Executive Summary 5 3 Location & Context 7 4 Topography & Landscape 9 5 History & Archaeology 10 6 City Landmarks 16 7 Building Materials 17 8 Building Types 18 9 Building Pattern 23 10 Public Realm 24 11 Policies & Guidelines 31 12 Opportunities & Constraints 37 13 Introduction to Character Areas 38 14 Cultural Spaces 41 Character Area 1: Stowe Pool 41 Character Area 2: Museum Gardens & Minster Pool 46 Character Area 3: Cathedral Close 53 Character Area 4: Friary & Festival Gardens 61 15 Residential Outskirts 69 Character Area 5: Stowe 69 Character Area 6: Beacon Street (north) 76 Character Area 7: Gaia Lane 83 Character Area 8: Gaia Lane Extension 89 16 Commercial Core 97 Character Area 9: Bird Street & Sandford Street 97 October 2008 Lichfield City Conservation Area Appraisal Character Area 10: St. John Street 104 Character Area 11: City Core 109 Character Area 12: Tamworth Street & Lombard Street 117 Character Area 13: Birmingham Road 127 Character Area 14: Beacon Street (south) 136 October 2008 1 Introduction 1.1 The Lichfield City Centre Conservation Area was first designated on 3rd March 1970 to cover the centre of the historic city. It was extended on 6th October 1999 to include further areas of Gaia Lane and St Chad’s Road. In June 1998 the Lichfield Gateway Conservation Area was designated covering the area around Beacon Street. For the purposes of this appraisal these two conservation areas will be integrated and will be known as the Lichfield City Conservation Area. The conservation area covers a total of 88.2 hectares and includes over 200 listed buildings. -

Curborough, Elmhurst, Farewell and Chorley Parish Council 12 March 2020

Curborough, Elmhurst, Farewell and Chorley Parish Council 12 March 2020 In attendance: Councillor Brown, Keen, Derry, Tisdale, Jennings, Mejor, Gulliver and Smith. Also in attendance: Members of public: 2 Other Councillors:0 Clerk: Ellen Bird 1. Apologies for Absence Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Packwood, Hammersley, Robinson, Bailey and Councillor Strachan, Lichfield District Council (LDC) and Councillor Tittley, Staffordshire County Council (SCC) Noted 2. Declarations of Interest There were none. 3. Chairman’s Opening Remarks The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. The Chair asked that with the likely impact of social isolation for Coronavirus, (which were likely to be announced over the next few days) that Councillors work with their communities to look after vulnerable and older residents. Staffordshire Parish Council Association (SPCA) and the National Association for Local Councils (NALC) would be informing Clerk’s about any legalities that would affect the Parish. Noted 4. Public Forum Potholes A local resident reported large pot holes on Grange Lane and the A515 near Seedy Mill Golf Club. Resolved to ask the Clerk to report these issues to SCC Highways. 1 Date: Signed: 5. To approve the minutes from 9 January 2020 Resolved to a) approve the Parish Meeting minutes held on 9 January 2020. The Minutes were signed by the Chair. b) Approve the adoption of the defibrillator in Chorley by the Parish Council and add it to the Council’s Asset Register c) Ask the Clerk to investigate whether the defibrillator in Chorley could be insured through the Parish Council. Councillors resolved to appoint the following Councillors as signatories on the bank mandate - Jenny Smith - Dorothy Robinson - Sally Keen - Linda Jennings 6. -

Prospectus Choosing the Right School for Your Child Is One of the Most Important Decisions Any Parent Will Face

Prospectus Choosing the right school for your child is one of the most important decisions any parent will face. I hope this prospectus will tell you all you need to know about Thomas Russell Junior School, to help you make that decision and give you a feel of what makes our school a happy and successful place. At Thomas Russell Junior School we aim to provide the best possible education for every child in a friendly and caring environment. We take great pleasure in forming strong relationships with parents and the wider community. We want each and every child to discover and achieve their potential, both academically and personally; to be stimulated and challenged; to take responsibility and most of all to enjoy their time here. Welcome to Thomas Russell Junior School. Mrs Shelley Sharpe Headteacher A word from the Chair of Governors Welcome to Thomas Russell Junior School. Whether you are new to the school or have older children here, we want your child to feel safe, happy and eager to learn about new things. We encourage good behaviour, a caring attitude and personal responsibility amongst our children. Our teachers have a wealth of experience and are well qualified to provide a broad range of educational opportunities. We will provide the best possible education that we can to all of the children in our school, and we want you and your family to share in helping us to achieve that. We welcome you and your family to Thomas Russell Junior School and look forward to you all having a happy and rewarding time here. -

The Flora of Staffordshire, 2011

The Flora of Staffordshire, 2011. Update No. 5 (October, 2015). 1. Add itional Herbarium Records. The online project Herbaria@home involves volunteers digitising the information from the herbarium sheets held by museums and universities. The results to date, relating to Staffordshire specimens, have been examined. Not all specimens were correctly identified by the original recorder. In particular the names applied to some Rosa and many Rubus specimens conflict with modern taxonomy. However, there are several important early records not included in this or earlier Floras. As a consequence, the previously thought earliest date for some taxa needs to be corrected; and a few significant later records need to be added. The resulting modified species accounts are given below. Page 107 At the bottom left, add to the abbreviations used for herbaria: BON Bolton Museum SLBI South London Botanical Institute Page 109 Equisetum hyemale L. Rough Horsetail 2 (0) 1796 Native Streamsides and ditches. It had not been recorded for the vice-county during the 20th Century until 1960, when it was collected by Dr Dobbie from a hedgerow at Bobbington, SO8090 (near to the county border), BON. Later seen in 1989, when RM found it on a streambank in Nash Elm Wood, SO7781. It remains at this site, and in 2003 it was reported by IJH to be present along a ditch and in adjacent marshy ground at Moddershall, SJ9237. Page 130 Ranunculus penicillatus (Dumort.) Bab. Stream Water-crowfoot 19 (2) 1876 Native In rivers, streams and brooks. All but two of the recent records are mapped as R. penicillatus ssp. -

Whittington to Handsacre HS2 London-West Midlands May 2013

PHASE ONE DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Community Forum Area Report 22 | Whittington to Handsacre HS2 London-West Midlands May 2013 ENGINE FOR GROWTH DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Community Forum Area Report ENGINE FOR GROWTH 22 I Whittington to Handsacre High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2nd Floor, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk © Crown copyright, 2013, except where otherwise stated Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. To order further copies contact: DfT Publications Tel: 0300 123 1102 Web: www.dft.gov.uk/orderingpublications Product code: ES/30 Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. CFA Report – Whittington to Handsacre/No 22 I Contents Contents Draft Volume 2: Community Forum Area Report – Whittington to Handsacre/No 22 5 Part A: Introduction 6 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Introduction to HS2 7 1.2 Purpose of this report 7 1.3 Structure of this report 9 Part B: Whittington -

Sites with Planning Permission As at 30.09.2018)

Housing Pipeline (sites with Planning Permission as at 30.09.2018) Not Started = Remaining Cumulative Total Outline Planning Application Decision Capacity Under Full Planning Parish Address Capacity For monitoring Completions (on partially Planning Number. Date* of Site Construction completed sites upto & Permission Year Permission including 30.09.18) 2 Mayfield Hall Hall Lane Middle Mayfield Staffordshire DE6 2JU P/2016/00808 25/10/2016 3 3 0 0 0 3 3 The Rowan Bank Stanton Lane Ellastone Staffordshire DE6 2HD P/2016/00170 05/04/2016 1 1 0 0 0 1 3 Stanton View Farm Bull Gap Lane Stanton Staffordshire DE6 2DF P/2018/00538 13/07/2018 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Adjacent Croft House, Stubwood Lane, Denstone, ST14 5HU PA/27443/005 18/07/2006 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Land adjoining Mount Pleasant College Road Denstone Staffordshire ST14 5HR P/2014/01191 22/10/2014 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Proposed Conversion Doveleys Rocester Staffordshire P/2015/01623 05/01/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Dale Gap Farm Barrowhill Rocester Staffordshire ST14 5BX P/2016/00301 06/07/2016 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Brown Egg Barn Folly Farm Alton Road Denstone Staffordshire P/2016/00902 24/08/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Alvaston and Fairfields College Road Denstone ST14 5HR P/2017/00050 10/08/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 1) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/00571 17/08/2017 5 0 5 0 5 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 2) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/01180 08/12/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 adj Cherry Tree Cottage Hollington Road Rocester ST14 5HY P/2018/00585 09/07/2018 1 -

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the City Of

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the city of Lichfield in Lichfield District Council area: Specialist Housing for Older People December 2018 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 1 Contents 1 Lichfield City Mapping ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Lichfield City Population Demographics ..................................................................... 3 1.2 Summary of demographic information ..................................................................... 11 1.3 Lichfield Locality Analysis .......................................................................................... 12 1.4 Access to Local Facilities and Services ...................................................................... 12 1.5 Access to local care facilities/age appropriate housing in Lichfield ......................... 23 2 Lichfield summary ............................................................................................................. 30 2.1 Lichfield Locality Population Demographics ............................................................. 30 2.2 Access to retail, banking, health and leisure services ............................................... 31 2.3 Access to specialist housing and care facilities ......................................................... 32 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 2 1 Lichfield City Mapping A 2km radius from the post code WS13 6JW has been set for the locality analysis which -

Cannock Chase to Sutton Park Draft Green Infrastructure Action Plan

Cannock Chase to Sutton Park Draft Green Infrastructure Action Plan Stafford East Staffordshire South Derbyshire Cannock Chase Lichfield South Staffordshire Tam wo r t h Walsall Wo lver ha mp ton North Warwickshire Sandwell Dudley Birmingham Stafford East Staffordshire South Derbyshire Cannock Chase Lichfield South Staffordshire Tam wor t h Wa l s al l Wo lv e r ha mpt on North Warwickshire Sandwell Dudley Birmingham Stafford East Staffordshire South Derbyshire Cannock Chase Lichfield South Staffordshire Ta m wo r t h Walsall Wo lverha mpton North Warwickshire Sandwell Dudley Birmingham Prepared for Natural England by Land Use Consultants July 2009 Cannock Chase to Sutton Park Draft Green Infrastructure Action Plan Prepared for Natural England by Land Use Consultants July 2009 43 Chalton Street London NW1 1JD Tel: 020 7383 5784 Fax: 020 7383 4798 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Introduction........................................................................................ 1 Purpose of this draft plan..........................................................................................................................1 A definition of Green Infrastructure.......................................................................................................3 Report structure .........................................................................................................................................4 2. Policy and strategic context .............................................................. 5 Policy review method.................................................................................................................................5 -

A Great Historic Spectacle - the Sheriff’S Ride

Autumn 2012 Website: www.beaconstreetara.org Email: [email protected] A Great Historic Spectacle - The Sheriff’s Ride. If you had been in Beacon Street on the morning of Saturday 8th September, you probably would have seen Lichfield’s current Sheriff, Mr. Brian Bacon, being driven slowly up the street in a bright pink Cadillac. Following behind was the splendid sight of 50 beautifully turned out horses and their riders, all taking part in the 2012 Sheriff’s Ride. Some horses from Cannock Chase Trekking Centre We must thank and congratulate Lichfield City Council for continuing to support and organise this historic event. If you enjoy a good day’s riding, you could join next year’s ride and be part of Lichfield’s proud heritage in 2013. Riders acknowledging Beacon Street residents This annual event started in 1553, when Queen Mary granted Lichfield County status. The Sheriff was ordered to perambulate the boundary of the County and City of Lichfield once a year. Nowadays the Ride covers a scenic 20 mile route around Lichfield before returning down Beacon Street at about six o’clock; when the Sheriff is met by the Sword and Mace Bearers at the corner of Anson Avenue. The party is then led to the Cathedral where they are welcomed by the Dean. After a short refreshment stop, the Ride makes its way to the Guildhall where it finishes and the riders disperse. - 1 - extra work party on 21st October to hopefully clear Let’s Support Pipe Green as far as the bridge. A big thanks to everyone who came along and helped in September”.