T Easy' How #Blackgirlmagic Created an Innovative Narrative for Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Due Process and the Disappearance of Black Girls in Public Education

#BLACKGIRLMAGIC: DUE PROCESS AND THE DISAPPEARANCE OF BLACK GIRLS IN PUBLIC EDUCATION ERICA YOUNG* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 209 II. BACKGROUND ......................................................................... 211 A. #BlackGirlMagic ................................................................ 211 B. Individuals with Disabilities Act ........................................ 212 C. Education for all Handicapped Children Act of 1975 ....... 214 D. Title IX ................................................................................ 215 II. DUE PROCESS .......................................................................... 215 A. Due Process ........................................................................ 215 B. Due Process: Special Education ........................................ 216 C. Due Process: Suspension and Expulsion ........................... 218 III. SPECIAL EDUCATION .............................................................. 219 A. Gender Disparity in Special Education .............................. 219 B. Racial Disparity in Special Education ............................... 222 C. The Intersection of Race and Gender for African AMerican Girls ........................................................................................ 225 IV. SCHOOL DISCIPLINE ............................................................... 226 A. The Impact of the Ghetto Black Girl .................................. 226 B. School Discipline -

Our Science, Her Magic

DIVERSE INTELLIGENCE SERIES | 2017 AFRICAN-AMERICAN WOMEN: OUR SCIENCE, HER MAGIC Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company FOREWORD WHAT IS #BLACKGIRLMAGIC? AND Cheryl Grace Senior Vice President, WHY SHOULD YOU CARE? U.S. Strategic Community Alliances and Consumer While the term #BlackGirlMagic is universally understood amongst Engagement African-Americans, it may require some context for others. Recently, an editor at Essence Magazine defined it as, “A term used to illustrate the universal awesomeness of Black women.” While it started as a social media hashtag and rallying call for Black women and girls to share images, ideas and sources of pride in themselves and other Black females, it has also become an illustration of Black women’s unique place of power at the intersection of culture, commerce and consciousness. African-American Women: Our Science, Her Magic is Nielsen’s seventh look Andrew McCaskill at African-American consumers and the second time we’ve focused Senior Vice President, our attention on Black women. Now more than ever, African-American Global Communications and Multicultural women’s consumer preferences and brand affinities are resonating across Marketing the U.S. mainstream, driving total Black spending power toward a record $1.5 trillion by 2021. At 24.3 million strong, Black women account for 14% of all U.S. women and 52% of all African-Americans. In the midst of data chronicling her steady growth in population, income and educational attainment, the overarching takeaway for marketers and content creators is to keep “value and values” top of mind when thinking about this consumer segment. Black women’s values spill over into all the things they watch, buy and Rebecca K. -

Black Girl Magic?: Negotiating Emotions and Success in College Bridge Programs Olivia Ann Johnson University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School June 2017 Black Girl Magic?: Negotiating Emotions and Success in College Bridge Programs Olivia Ann Johnson University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Johnson, Olivia Ann, "Black Girl Magic?: Negotiating Emotions and Success in College Bridge Programs" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Girl Magic?: Negotiating Emotions and Success in College Bridge Programs by Olivia Ann Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, Ph.D. Aisha Durham, Ph.D. Julia Meszaros, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 15, 2017 Keywords: race, emotion, emotional respectability, education, gender Copyright © 2017, Olivia A. Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iii Introduction: Do you believe in Magic? ..............................................................................1 -

"Get in Formation:" a Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Sina H

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2018 When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Sina H. Webster Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Webster, Sina H., "When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade" (2018). Senior Honors Theses. 568. https://commons.emich.edu/honors/568 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. When Life Gives You Lemons, "Get In Formation:" A Black Feminist Analysis of Beyonce's Visual Album, Lemonade Abstract Beyonce's visual album, Lemonade, has been considered a Black feminist piece of work because of the ways in which it centralizes the experiences of Black women, including their love relationships with Black men, their relationships with their mothers and daughters, and their relationships with other Black women. The album shows consistent themes of motherhood, the "love and trouble tradition," and Afrocentrism. Because of its hint of Afrocentrism, however, Lemonade can be argued as an anti Black feminist work because Afrocentrism holds many sexist beliefs of Black women. This essay will discuss the ways in which Lemonade's inextricable influences of Black feminism and Afrocentrism, along with other anti Black feminist notions, can be used as a consciousness-raising tool. -

Complete 2020 Program

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference 2020, 31st Annual JWP Conference Apr 4th, 8:30 AM - 9:00 AM Complete 2020 Program Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc Part of the Education Commons Illinois Wesleyan University, "Complete 2020 Program" (2020). John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference. 4. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc/2020/schedule/4 This Event is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at The Ames Library at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Named for explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell, the Student Research Conference gives undergraduate students at Illinois Wesleyan University the opportunity to share their intellectual and creative work. The Conference showcases the accomplishments of students across programs, providing a forum for research in a variety of fields to be presented to an engaged audience. Honoring SATURDAY, APRIL 4 John Wesley Powell’s commitment to a broad, student-centered education in the liberal arts, the Conference celebrates student achievement and the sharing of 2020 cross-disciplinary knowledge. -

Of Producing Popular Music

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-26-2019 1:00 PM The Elements of Production: Myth, Gender, and the "Fundamental Task" of Producing Popular Music Lydia Wilton The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Coates, Norma. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Music © Lydia Wilton 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Wilton, Lydia, "The Elements of Production: Myth, Gender, and the "Fundamental Task" of Producing Popular Music" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6350. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6350 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Using Antoine Hennion’s “anti-musicology”, this research project proposes a methodology for studying music production that empowers production choices as the primary analytical tool. It employs this methodology to analyze Kesha’s Rainbow, Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer, and St. Vincent’s Masseduction according to four, encompassing groups of production elements: musical elements, lyrical elements, personal elements, and narrative elements. All three albums were critical and commercial successes, and analyzing their respective choices offers valuable insight into the practice of successful producers that could not necessarily be captured by methodologies traditionally used for studying production, such as the interview. -

(Miss) Representation: an Analysis of the Music Videos and Lyrics of Janelle Monae As an Expression of Femininity, Feminism

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 2019 (Miss) Representation: An Analysis of the Music Videos and Lyrics of Janelle Monae as an Expression of Femininity, Feminism, and Female Rage Amy Dworsky Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Communication Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Dworsky, Amy, "(Miss) Representation: An Analysis of the Music Videos and Lyrics of Janelle Monae as an Expression of Femininity, Feminism, and Female Rage" (2019). Honors College Theses. 218. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/218 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEADER: (MISS)REPRESENTATION (Miss) Representation: An Analysis of the Music Videos and Lyrics of Janelle Monae as an Expression of Femininity, Feminism, and Female Rage Amy Dworsky Communication Studies Advisor: Emilie Zaslow Dyson School of Arts and Sciences, Communications Department May 2019 Pace University MISS(REPRESENTATION) 1 Abstract Women in music videos have long been portrayed as sexual objects. With movements such as #MeToo and #TimesUp, artists are challenging the the construction of femininity and feminism. Some artists are using their artistic expressions to challenge the sexualization of women in music videos and are giving voice to the rage they experience in a misogynist culture that endorses a misogynist president. The shift in societal norms, taking into account the politically charged atmosphere, has created a new wave of feminism through popular music and popular culture. -

I AM My Hair, and My Hair Is Me: #Blackgirlmagic in LIS Teresa Y

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository University Libraries & Learning Sciences Faculty Scholarly Communication - Departments and Staff ubP lications Fall 9-2018 I AM My Hair, and My Hair is Me: #BlackGirlMagic in LIS Teresa Y. Neely PhD University of New Mexico - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ulls_fsp Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Neely, Teresa Y. “I AM My Hair, and My Hair is Me: #BlackGirlMagicinLIS”. In Pushing the Margins: Women of Color and Intersectionality in LIS, edited by Rose l. Chou and Annie Pho, 121-146. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press, 2018. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarly Communication - Departments at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries & Learning Sciences Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I AM My Hair, and My Hair Is Me: #BlackGirlMagic in LIS Teresa Y. Neely, Ph.D. No matter who you are, no matter where you come from, you are beautiful, you are powerful, you are brilliant, you are funny… I know that’s not always the message that you get from the world. I know there are voices that tell you that you’re not good enough. That you have to look a certain way, act a certain way. That if you speak up, you’re too loud. If you step up to lead, you’re being bossy --Michelle Obama In her 2015 Black Girls Rock (BGR) awards speech, Michelle Obama spoke directly to women and girls who look like me. -

“Black Girl Magic and Lemonade” a Collection of Short Stories by Nicole Huff

“Black Girl Magic and Lemonade” A Collection of Short Stories by Nicole Huff English Department Dr. Shanna Salinas A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts at Kalamazoo College 2016 ii Preface My African American Literature class provided me with the materials that sparked my interest to conduct a SIP surrounding the concept of blackness, and more specifically, black feminism. The coursework that I have completed throughout my time at Kalamazoo College, were mostly literature and writing classes. Most of the literature classes that I took somehow always centered themselves around the topic of race and racism, and the way that we analyze literature of previous-colonized people in America. African American Literature, Junior Seminar, and Intermediate Fiction were the classes that I consider the most important to the growth and development of my SIP topic. My newly understood knowledge of different theories and my ability to apply them to my fiction to create an understanding of bigger topics come from my work in Junior Seminar. During my African American Literature class, I wrote a lengthy paper on Audre Lorde’s idea of self- actualization in black identity in correlation with the relationship between black and white females as well as black males and females. I did this after reading a few chapters in her compilation of speeches and essays, Sister Outsider. Lorde’s interpretation of these relationships between black men and women as well as black women and white women generated higher interest in the relationship between black women and white males as well. -

Curriculum Unit (PDF)

The Power of Black Girl Mathgic: An Exploration of Black Women in STEM By Gold Gladney, 2020 CTI Fellow Wilson STEM Academy This curriculum unit is recommended for: 6th Grade Standard Math and 6th Grade Honors Math Keywords: Black, girl, magic, math, mathgic, STEM Teaching Standards: See Appendix 1 for teaching standards addressed in this unit. Synopsis: This unit will highlight Black women in STEM, emphasize the importance of increasing the percentage of Black women working in STEM careers, and explore the many ways math connects to African American culture especially related to Black women. The ultimate goal is for students to see themselves in STEM positions in the future. This will be accomplished through learning various stories of Black women in STEM while simultaneously gaining a stronger understanding of math concepts. This unit plan will be rigorous, culturally appropriate, and culturally responsive. I believe engaging students in this unit will entice them and create greater investment in future math courses. When students are invested, they put forth stronger efforts in the course. This leads to stronger end of grade results. More importantly, students will develop self-awareness, self-confidence, and cultural pride that will stick with them throughout the duration of their educational career and perhaps their lifetime. I plan to teach this unit during the coming year to 90 students in 6th Grade Standard Math and 6th Grade Honors Math. I give permission for Charlotte Teachers Institute to publish my curriculum unit in print and online. I understand that I will be credited as the author of my work. -

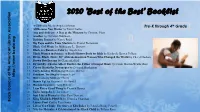

BCALA-2020-Best-Of-The-Best.Pdf

2020 'Best of the Best' Booklist 1. A Girl Like Me by Angela Johnson Pre-K through 4th Grade 2. All Because You Matter by Tami Charles 3. Ana and Andrew: A Day at the Museum by Christine Platt 4. Another by Christian Robinson 5. Bedtime Bonnet by Nancy Redd 6. Big Papa and the Time Machine by Daniel Bernstrom 7. Black Girl Magic by Mahogany L. Browne 8. Black is a Rainbow Color by Angela Joy 9. Black Women in Science: A Black History Book for Kids by Kimberly Brown Pellum 10. Brave. Black. First.: 50+ African American Women Who Changed the World by Cheryl Hudson 11. Brown Boy Dreams by Clamentia Hall 12. By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, the Father of Gospel Music by Carole Boston Weatherford 13. Carter Reads the Newspaper by Deborah Hopkinson 14. Early Sunday Morning by Denene Millner 15. Freedom, We Sing by Amyra Leon https://www.bcala.org 16. Hair Love by Matthew Cherry 17. Hands Up! by Breanna J. McDaniel 18. Harlem Grown by Tony Hillery 19. I Am Every Good Thing by Derrick Barnes 20. Jayla Jumps In by Joy Jones 21. Just Like A Mama by Alice Faye Duncan 22. King Khalid Is PROUD by Veronica Chapman Black Caucus of the American Library Association American the of Black Caucus 23. Liam's First Cut by Taye Jones 24. Lift as You Climb: The Story of Ella Baker by Patricia Hruby Powell 25. M is for Melanin: A Celebration of the Black Child by Tiffany Rose 2020 'Best of the Best' Booklist 26. -

Blackgirlmagic and the Black Ratchet Imagination

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 15 Issue 1—Spring 2019 Breaking Binaries: #BlackGirlMagic and the Black Ratchet Imagination S.R. Toliver Abstract: CaShawn Thompson’s hashtag, #BlackGirlMagic, has transformed into a movement over the past five years. The hashtag focuses on celebrating the beauty,& influence, and strength of Black women and girls. However, Thompson’s term sits in a space of tension, where contradictory interpretations create boundaries around what Black girl celebration means as well as who gets to celebrate Black girl magic, specifically when it comes to girls without a celebrity status and girls who are considered hood or ratchet. In this paper, the author contends that the tension between respectability and ratchetness must be further explored, as it is an essential component in discussions of Black girl identities. To do this, the Afrofuturist young adult literature of Nnedi Okorafor is analyzed using a conceptual framework that highlights the Black Ratchet Imagination and its aversion to respectability politics and the ways in which Afrofuturism challenges notions of respectability in terms of traditional Black literary cultural production. Findings suggest that, although each character, like real Black girls, exhibits traits of respectability, they also depict traits of ratchetness. Thus, the author calls for all literacy stakeholders to dissolve preconceived binaries and conceptualize ratchetness as another celebratory space of agency and Black Girl Magic. Keywords: #BlackGirlMagic, Black Ratchet Imagination, Afrofuturism, Critical Content Analysis, Black Girls S.R. Toliver is pursuing a Ph.D. in language and literacy education at The University of Georgia. Her research centers representations of and responses to people of color in speculative fiction and popular culture texts, and she is also interested in critical literacy, secondary education, Afrofuturism, social justice, and Black girl literacies.