Analysis of a Skyscraper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VICKI BITNER Vicki Bitner Practices in the Area of Complex Civil and Commercial Litigation

VICKI BITNER Vicki Bitner practices in the area of complex civil and commercial litigation. For more than 20 years, she has represented individual, corporate, non-profit, and government clients in a wide range of litigation matters, including breach of contract, minority shareholder disputes, unfair or deceptive trade practices, rights to intellectual property, and provider reimbursement (hospitals and nursing facilities). She also has significant experience representing clients in [email protected] litigation over actions taken by state and federal government agencies. 612.756.7777 fax: 612.337.5151 Before joining the Briol law firm, Ms. Bitner worked for ten years in Washington, D.C. During this time she practiced with the law firm of Covington & Burling, served as a special prosecutor with the Office of Independent Counsel, and was a law clerk to the Honorable Oliver Gasch, U.S. District Court 3700 IDS Center for the District of Columbia. 80 South Eighth Street Minneapolis, MN 55402 Ms. Bitner received her J.D. with high honors from the George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., where she served as Editor-in-Chief of the Law Review and graduated Order of the Coif. She received her B.A. from the University of Minnesota. She is admitted to practice in Minnesota and the District of Columbia. EDUCATION George Washington University National Law Center J.D., high honors, 1989 Order of the Coif Editor-in-Chief, The George Washington Law Review University of Minnesota B.A., 1984 VICKI BITNER BAR & COURT ADMISSIONS Minnesota Supreme Court District of Columbia Court of Appeals U.S. -

Zoning ORDINANCE USER's MANUAL

CITY OF PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL PRODUCED BY CAMIROS ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL WHAT IS ZONING? The Zoning Ordinance provides a set of land use and development regulations, organized by zoning district. The Zoning Map identifies the location of the zoning districts, thereby specifying the land use and develop- ment requirements affecting each parcel of land within the City. HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL This User’s Manual is intended to provide a brief overview of the organization of the Providence Zoning Ordinance, the general purpose of the various Articles of the ordinance, and summaries of some of the key ordinance sections -- including zoning districts, uses, parking standards, site development standards, and administration. This manual is for informational purposes only. It should be used as a reference only, and not to determine official zoning regulations or for legal purposes. Please refer to the full Zoning Ordinance and Zoning Map for further information. user'’S MANUAL CONTENTS 1 ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ZONING DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 USES............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N 980314 ZRM Subway

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION July 20, 1998/Calendar No. 3 N 980314 ZRM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the Department of City Planning, pursuant to Section 201 of the New York City Charter, to amend various sections of the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York relating to the establishment of a Special Lower Manhattan District (Article IX, Chapter 1), the elimination of the Special Greenwich Street Development District (Article VIII, Chapter 6), the elimination of the Special South Street Seaport District (Article VIII, Chapter 8), the elimination of the Special Manhattan Landing Development District (Article IX, Chapter 8), and other related sections concerning the reorganization and relocation of certain provisions relating to pedestrian circulation and subway stair relocation requirements and subway improvements. The application for the amendment of the Zoning Resolution was filed by the Department of City Planning on February 4, 1998. The proposed zoning text amendment and a related zoning map amendment would create the Special Lower Manhattan District (LMD), a new special zoning district in the area bounded by the West Street, Broadway, Murray Street, Chambers Street, Centre Street, the centerline of the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River and the Battery Park waterfront. In conjunction with the proposed action, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development is proposing to amend the Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan (located in the existing Special Manhattan Landing District) to reflect the proposed zoning text and map amendments. The proposed zoning text amendment controls would simplify and consolidate regulations into one comprehensive set of controls for Lower Manhattan. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

IDS CENTER Minneapolis, Minnesota Kemper Waterproofing Membrane Ensures Crystal Court’S First Dry Winter

Project Profile: IDS CENTER Minneapolis, Minnesota Kemper waterproofing membrane ensures Crystal Court’s first dry winter The IDS Center’s Crystal Court, part of the landmark IDS Tower of the Minneapolis skyline and the centerpiece of one of the world’s most extensive skyway systems, is the primary gathering place in downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is the one place where business and commerce converge daily in temperature-controlled comfort without having to go outside. Over four years ago, Tom Cowhey, the IDS Center Operations Manager for the past quarter- century, asked AMBE LTD., a roofing, waterproofing and building envelope consulting firm based in Minneapolis, to determine what product would seal and waterproof the roof of the IDS Crystal Court. The Crystal Court has eight different levels with a total of 289 skylights separated by a narrow 10-inch gutter. Waterproofing these gutters between the skylights has been extremely difficult, and the yellow “wet floor” signs were never consistent with the quality and character of this icon property. With leaks that had occurred in the Crystal Court since initial construction, the task of finding the right waterproofing and roofing system proved a major undertaking for Richard Grobovsky of AMBE LTD. The problem was how to run an inconspicuous waterproofing project directly above the estimated 50,000 people who walk through the Crystal Court on a daily basis. Design of the waterproofing system is difficult in itself, but the safety of the general public, safe access and safe working surfaces for the roofers, and the project’s appearance were all factors that required consideration. -

Johan Akesson

NATIONAL FEDERATION OF MUNICIPAL ANALYSTS ADVANCED SEMINAR ON HEALTH CARE DISNEY’S GRAND FLORIDIAN ORLANDO, FLORIDA JANUARY 15 & 16, 2009 REGISTRATION LIST 2 Johan Akesson Jay Alfirevic Associate Portfolio Manager Managing Director Thrivent Financial Wellspring Partners 625 Fourth Avenue South, Mail Stop 1010 123 N Wacker Dr, Ste 900 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415 Chicago, Illinois 60521 612 844-6841 312-880-3037 [email protected] [email protected] Shelley Aronson Martin Arrick President Managing Director First River Advisory L.L.C. Standard & Poor's 2640 Overridge Drive 55 Water St, 38th Floor Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 New York, New York 10041 734-761-3624 212-438-7963 [email protected] [email protected] David Belton Holly Benson Head of Municipal Bond Research Secretary Standish Mellon Asset Management Florida Agency for Health Care BNY Mellon Center, 201 Washington Street 2727 Mahan Drive Boston, Massachusetts 02108-4408 Tallahassee, Florida 32308 (617) 248-6039 (888) 419-3456 [email protected] Derek Bonifer Iain Briggs Director Managing Director BMO Capital Markets FTI Healthcare 233 S Wacker Dr, 300 Sears Tower 100 Westwood Place, Ste 350 Chicago, Illinois 60606 Brentwood, Tennessee 37027 312-441-2563 615 324-8522 [email protected] [email protected] 3 Jeffrey Burger Hanan Callas Senior Analyst & Portfolio Manager VP, Senior Investment Analyst Columbia Management Federated Investors One Financial Center, 13th Fl, Ma5-515-13-02 1001 Liberty Ave Boston, Massachusetts 2111 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222-3779 617-772-3798 412 288-7799 [email protected] [email protected] Rebecca Chahid Richard Ciccarone Fixed Income Analyst McDonnell Investment Mgmt. -

Committee Leadership 2017-2018

COMMITTEE LEADERSHIP 2017-2018 As of 2/8/18 AIPLA Fellows Denise M. Kettelberger (Chair) Troy Grabow (Board Liaison) Sunstein Kann Murphy & Timbers LLP Cabeau, Inc. 125 Summer Street 5850 Canoga Ave. Boston, MA 02110 Suite 100 617-443-9292 Woodland Hills, CA 91367 [email protected] 818-743-9434 [email protected] Philip Petti (Vice-Chair) USG Corporation 550 West Adams Street Chicago, IL 60661 312-436-4590 [email protected] AIPPI-US Division of AIPLA Maria A. Scungio (Chair) Monica M. Barone (Board Liaison) Wolf, Greenfield & Sacks, P.C. Qualcomm Incorporated 405 Lexington Avenue 5775 Morehouse Drive New York, NY 10174 San Diego, CA 92121 212-336-3848 858-845-1916 [email protected] [email protected] Marc Richards (Vice-Chair) Brinks Gilson & Lione 455 N Cityfront Plaza Dr NBC Tower - Suite 3600 Chicago, IL 60611-5503 312-321-4729 [email protected] Alternative Dispute Resolution William L. LaFuze (Chair) Barbara A. Fiacco (Board Liaison) McKool Smith Foley Hoag, LLP 600 Travis Street, Suite 7000 Seaport West Houston, TX 77002 155 Seaport Blvd 713 485-7307 Boston, MA 02210-2600 [email protected] 617-832-1227 [email protected] Paul E. Burns (Vice-Chair) Procopio Cory Hargreaves & Savitch LLP 525 B Street Suite 2200 San Diego, CA 92101-4474 619-525-3877 [email protected] Amicus Robert O. Lindefjeld (Chair) Barbara A. Fiacco (Board Liaison) Nantero, Inc. Foley Hoag LLP 112 Marshall Drive 155 Seaport Blvd. Pittsburgh, PA 15228 Boston, MA 02210-2600 412-480-1797 617-832-1227 [email protected] [email protected] Doris Hines (Vice-Chair) Finnegan, Henderson - DC 901 New York Ave Nw Washington, DC 20001-4432 202-408-4250 [email protected] Anti-Counterfeiting and Anti-Piracy Gail E. -

Download Parking Guide

Knox Ave S Lagoon Ave Lagoon The Mall The The Mall The W Lake St Lake W W 31st St 31st W James Ave S James Ave S James Ave S James Ave S James Ave S W 31st St 31st W W Lake St Lake W Lagoon Ave Lagoon Mall The The Mall The Irving Ave S Irving Ave S Irving Ave S Irving Ave S Irving Ave S W St 28th Lake of the Isles Pkwy E I rvi ng A ve W 31st St 31st W W Lake St Lake W S The Mall The The Mall The Lagoon Ave Lagoon Humboldt Ave S Humboldt Ave S W St 28th Humboldt Ave S Humboldt Ave S Humboldt Ave S Irving A ve S W St 25th Humboldt Ave S W St 26th W 31st St 31st W W Lake St Lake W Euclid Pl 27th St W St 27th Irving A Midtown Greenway ve S The Mall The The Mall The A ve S Holmes Ave S Holmes Ave S Ave Lagoon Irving IrvingA ve S Humboldt 28th St W St 28th A ve S W St 25th 26th St W St 26th W Lake St Lake W W 31st St 31st W Humboldt 27th St W St 27th A ve S Hennepin Ave S Hennepin Ave S Hennepin Ave S Hennepin Ave S Hennepin Ave S HumboldtA ve S HumboldtA ve S HumboldtA ve S HumboldtA ve S 28th St W St 28th 26th St W St 26th Hennepin Ave S W St 1/2 25 W 31st St 31st W W Lake St Lake W 25th St W St 25th Lagoon Ave Lagoon 22nd St W St 22nd 24th St W St 24th Hennepin Ave S GirardA ve S GirardA ve S GirardA ve S GirardA ve GirardA ve S GirardA ve S 28th St W St 28th GirardA ve S GirardA ve S 27th St W St 27th 25th St W St 25th Hennepin Ave S W St 24th Lagoon Ave Lagoon 22nd St W St 22nd 26th St W St 26th Fremont A ve S AFremont ve S FremontA ve S FremontA ve S FremontA ve S 28th St W St 28th Hennepin Ave S Van White Blvd (proposed) AFremont ve -

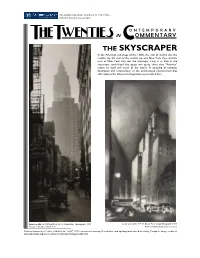

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Height, Setbacks, and Floor Area 17.48

HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA 17.48 Chapter 17.48 – HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA Sections: 17.48.010 Purpose 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.030 Setback Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.040 Floor Area and Floor Area Ratio 17.48.010 Purpose This chapter establishes rules for the measurement of height, setbacks, and floor area, and permitted exceptions to height and setback requirements. 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions A. Measurement of Height. 1. The height of a building is measured as the vertical distance from the assumed ground surface to the highest point of the building. 2. Assumed ground surface means a line on the exterior wall of a building that connects the points where the perimeter of the wall meets the finished grade. See Figure 17.48-1. 3. If grading or fill on a property within five years of an application increases the height of the assumed ground service, height shall be measured using an estimation of the assumed ground surface as it existed prior to the grading or fill. FIGURE 17.48-1: MEASUREMENT OF MAXIMUM PERMITTED BUILDING HEIGHT 48-1 17.48 HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA B. Height Exceptions. Buildings may exceed the maximum permitted height in the applicable zoning district as shown in Table 17.48-1. Note: Height exceptions in Table 17.48-1 below add detail to height exceptions in Section 17.81.070 of the existing Zoning Code. TABLE 17.48-1: ALLOWED PROJECTIONS ABOVE HEIGHT LIMITS Maximum Projection Above Structures Allowed Above Height Limit Maximum Coverage Height Limit Non-habitable decorative features including 3 ft.