The State of Sustainable Markets 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBI Product Factsheet

CBI Product Factsheet: Tea in the Netherlands Introduction The Netherlands is the fifth-largest tea-consuming country in Europe. The majority of opportunities exist in the area of high-quality and value-added products (e.g. loose tea, green tea, herbal/traditional medicinal tea and slimming tea). The Dutch market for certified tea is growing rapidly as well. Product Definition The word ‘tea’ refers to a hot beverage that is prepared by infusing or brewing the dried leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. There are at least six different types of tea: green, white, yellow, oolong, black, and dark post-fermented tea (or black tea for the Chinese). The most commonly found on the market are black, green, oolong and white (see table 1). Flavours of tea Oxidation is the distinguishing factor that determines whether tea leaves will become black, oolong, green or white tea. It is a chemical process that results in the browning of tea leaves and the production of flavour and aroma compounds in finished teas. During the oxidation process (sometimes also referred to as ‘fermentation’), the flavours and aromas of tea become fuller and deeper. In general, black tea is fully oxidised, oolong is partially oxidised, green tea is processed to stop oxidation (only minimal oxidation or no oxidation at all occurs) and white tea is unoxidised. Table 1: the most common teas and their flavours Tea Description Flavour Black tea Black tea is the most common type of tea in the Black tea is noted for its full, bold flavour and its ability to Western world. -

POLICY for FARM and CHAIN of CUSTODY CERTIFICATION in COCOA February 2021 Version 1.4

POLICY FOR FARM AND CHAIN OF CUSTODY CERTIFICATION IN COCOA February 2021 Version 1.4 More information? For more information about the Rainforest Alliance, visit www.rainforest-alliance.org or, for specific interpretation issues about this document contact [email protected]. Translation Disclaimer Rainforest Alliance makes every effort to ensure translation accuracy of all Rainforest Alliance sustainable agriculture certification program documents into languages other than English. Any question arising from interpretation of the document content in different languages should refer to the English official version as the reference document. Any discrepancies or differences created in the translation are not binding and have no effect for auditing or certification purposes. 2 Issue Date: Binding date: Expiration date: 14 April 2020 1 June 2020 Revised 7 July 2020, 16 September *see table below each section 1 July 2021 2020, 1 October 2020, 15 February for binding date of each 2021 specific criterion Developed by: Approved by: Rainforest Alliance Director, Standards and Assurance Linked to (code and name of documents, if applicable): UTZ related documents Rainforest Alliance related documents UTZ Assurance Certification protocol, version Rainforest Alliance Certification Rules, July 4.3 December 2018 Letter from April 18th, 2019 Important Notice: 2017 version 1.2 new requirements for UTZ and Rainforest Rainforest Alliance Chain of Custody Policy Certificate holders in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana 2015 UTZ Core Code of Conduct for group and Rainforest Alliance Sustainable Agriculture multi-group certification, version 1.1 + cocoa module Standard, July 2017 version 1.2 Chain of Custody Standard + Cocoa Annex Replaces The following measures from 2019 to strengthen the Cocoa Sector in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are not applicable any longer and the applicable rules from the UTZ Protocol v4.3 are applied: Extended timeframe for UTZ Code of Conduct audits Increased percentage of surprise audits for UTZ Code of Conduct from 10 to 15%. -

Sustainable Food Systems Concept and Framework

Sustainable food systems Concept and framework WHAT IS A SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEM? Food systems (FS) encompass the entire range of actors and their interlinked value-adding activities involved in the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food products that originate from agriculture, forestry or fisheries, and parts of the broader economic, societal and natural environments in which they are embedded. The food system is composed of sub-systems (e.g. farming system, waste management system, input supply system, etc.) and interacts with other key systems (e.g. energy system, trade system, health system, etc.). Therefore, a structural change in the food system might originate from a change in another system; for example, a policy promoting more biofuel in the energy system will have a significant impact on the food system. A sustainable food system (SFS) is a food system that delivers food security and nutrition for all in such a way that the economic, social and environmental bases to generate food security and nutrition for future generations are not compromised. This means that: – It is profitable throughout (economic sustainability); – It has broad-based benefits for society (social sustainability); and – It has a positive or neutral impact on the natural environment (environmental sustainability). A sustainable food system lies at the heart of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Adopted in 2015, the SDGs call for major transformations in agriculture and food systems in order to end hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition by 2030. To realize the SDGs, the global food system needs to be reshaped to be more productive, more inclusive of poor and marginalized populations, environmentally sustainable and resilient, and able to deliver healthy and nutritious diets to all. -

Implementation Guide UTZ CERTIFIED Good Inside Code of Conduct for Coffee

Implementation Guide UTZ CERTIFIED Good inside Code of Conduct for Coffee ISBN: 978-94-90283-04-9 www.utzcertified.org www.utzcertified-trainingcenter.com www.solidaridadnetwork.org UTZ CERTIFIED is a programme aimed at the sustainability of the market that improves professional agriculture and has a positive impact on productivity, quality and eciency. Project work team Vera Espindola Francisco Bustamante Diana Bedoya Solidaridad is a development organisation with the mission of reducing poverty through the chains of Carlos Isaza a sustainable supply of agro-products. Solidaridad considers that sustainable economic development Leonardo Sánchez is the best solution to structural poverty in developing countries. Solidaridad works in the chains of sustainable production from the producer to the consumer so that producers in developing countries can increase their capacity to manage a professional business. Design Mariana Álvarez Matijasevic UTZ CERTIFIED and Solidaridad has a strategic alliance, the creation of a support network for producers and an improvement programme to meet the needs of the producer and facilitates the Reviser quality and volume required by the market. Darío Ángel With the support of: UTZ CERTIFIED Good Inside ISBN: 978-94-90283-04-9 De Ruyterkade 1013 AA Amsterdam The Netherlands T: + 31 20 530 8031 This material is a product of a joint initiative by UTZ CERTIFIED and the SOLIDARIDAD Foundation. www.utzcertied.org. www.utzcertied-trainingcenter.com UTZ CERTIFIED is the intellectual property rights holder. It authorises the reproduction of all of the document for educational purposes only, provided that its integrity is preserved and the participating organisations are cited. Any other use of this document requires written authorisation from UTZ CERTIFIED. -

Shaping Sustainable Markets

Shaping sustainable markets A research initiative that seeks to ensure markets work to support, rather than undermine, sustainable development. In brief SSM analyses a wide range of market governance mechanisms — from carbon labelling to diamond certification — to explore how they are designed and how they impact people, the planet and the economy. A market governance mechanism is a set of formal rules consciously designed to change behaviour – of individuals, businesses, organisations or governments – to influence how markets work and their outcomes. Through research we identify which mechanisms are working well and which are not. Ultimately, we want to improve how market governance mechanisms are designed. We also explore the potential of innovative mechanisms that have yet to be tested in the real world — providing new ideas for ‘shaping’ markets. This work will be useful for policymakers, business professionals, and researchers and anyone who has an interest in how markets can work to support sustainable development. Our work Shaping Sustainable Markets builds on existing research. We make sure we don’t replicate work that has already been done but also aim to fill knowledge gaps where possible. Ultimately we hope to design a set of principles to guide policymakers in designing and implementing effective mechanisms. We are looking at individual mechanisms, such as specific payments for environmental services schemes, as well as groups of mechanisms, for example certification, using the typology we have developed. Over time, we aim -

Discovering Business Value in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Sdgs) Insights from the Inaugural Application of the Trucost SDG Evaluation Tool

Discovering Business Value in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Insights from the Inaugural Application of the Trucost SDG Evaluation Tool Prepared by Trucost November 2018 DISCOVERING BUSINESS VALUE IN THE UN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 1 Credits Project Director: Libby Bernick Managing Director, Global Head of Corporate Business Lead Authors: Rick Lord Manager | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery, and SDG Evaluation Project Manager Rochelle March Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Trucost Project Contributors: Sarah Aird Marketing Director Steven Bullock Global Head of Research Rebecca Edwards Marketing Manager Nikol Ioannou Senior Speciality | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery David McNeil Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Teri Mendelsohn Senior Product Lead Gautham P Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Deepti Panchratna Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Miriam Tarin Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Byford Tsang Senior Analyst | ESG Analytics and Client Delivery Alasdair Wilson Model and Valuations Manager About Trucost Trucost is part of S&P Global. A leader in carbon and environmental data and risk analysis, Trucost assesses risks relating to climate change, natural resource constraints, and broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors. Companies and financial institutions use Trucost intelligence to understand their ESG exposure to these factors, inform resilience, and identify transformative solutions for a more sustainable global economy. S&P Global's commitment to environmental analysis and product innovation enables its team to deliver essential 2 ESG investment-related information to the global marketplace. For more information, visit www.trucost.com. About S&P Global S&P Global (NYSE: SPGI) is a leading provider of transparent and independent ratings, benchmarks, analytics, and data to the capital and commodity markets worldwide. -

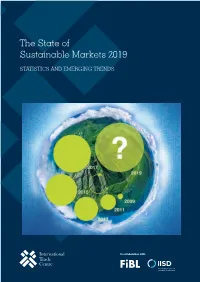

The State of Sustainable Markets 2019

The State of Sustainable Markets 2019 STATISTICS AND EMERGING TRENDS In collaboration with: How much has agricultural land certified as sustainable grown since 2011? This is the world’s most comprehensive report on sustainable markets, with data from 14 major sustainability standards for eight agricultural products, plus forestry. This chart gives a snapshot of sustainable land area (in hectares) certified by at least one standard from 2011 to 2017. It covers eight agricultural products, highlighted in the report. Note: This is a minimum. The actual land area is larger, as many producers have multiple certifications. THE STATE OF SUSTAINABLE MARKETS 2019 STATISTICS AND EMERGING TRENDS 17 924 420 ? 2017 2019 15 022 336 2015 2009 3 244 030 11 246 200 2011 7 539 945 2013 Sustainability standards continue their growth across the world. This fourth global report provides new insights into the evolution of certified agriculture and forestry. ITC has teamed up once again with the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture and the International Institute for Sustainable Development to provide data about 14 major sustainability standards for bananas, cocoa, coffee, cotton, oil palm, soybeans, sugarcane, tea and forestry products. This report helps shape decisions of policymakers, producers and businesses, working to address systemic labour and environmental challenges through certified sustainable production. Title: The State of Sustainable Markets 2019: Statistics and Emerging Trends Publisher: International Trade Centre (ITC), International Institute for Sustainable (IISD), Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) Publication date and place: October 2019, Geneva Page count: 72 Language: English ISBN: 978-92-1-103675-6 eISBN: 978-92-1-004614-5 Print ISSN: 2617-5452 eISSN: 2617-5460 United Nations Sales Number: E.19.III.T.5 ITC Document Number: P115.E/DEI/SIVC/19-X Citation: Helga Willer, Gregory Sampson, Vivek Voora, Duc Dang, Julia Lernoud (2019), The State of Sustainable Markets 2019 – Statistics and Emerging Trends. -

Towards More Sustainability in the Soy Supply Chain: How Can EU Actors Support Zero- Deforestation and SDG Efforts?

Towards more sustainability in the soy supply chain: How can EU actors support zero- deforestation and SDG efforts? November 2019 0 Towards more sustainability in the soy supply chain: How can EU actors support zero- deforestation and SDG efforts? For Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) 01 December 2019 Authors: Stasiek Czaplicki Cabezas Helen Bellfield Guillaume Lafortune Charlotte Streck Barbara Hermann Global Canopy Climate Focus 1 List of abbreviations Towards more sustainability in the soy supply chain Contents List of abbreviations 4 List of figures and tables 6 Foreword 7 Executive Summary 9 1. Introduction 15 1.1 Sustainability of soy 15 1.2 Objective, approach and scope of the report 16 1.3 Structure of this report 17 2. Supply chain market and sustainability context 19 2.1 Soybean commodity market analysis and outlook 19 2.2 Sustainable Development Goals and Soy 22 2.2.1 Transforming food and land-use systems to achieve the SDGs 22 2.2.2 Supply chain spill-over effects and the SDGs 24 2.2.3 Deforestation imported into the EU and China 32 3. Main stakeholders and agents of change 37 3.1 Global actors 38 3.2 Brazil 39 3.3 Argentina 40 3.4 EU 41 3.5 China 43 3.6 SDG reporting of main stakeholders 43 4. Policy instruments 47 4.1 Global initiatives 49 4.1.1 SDG reporting: UN Global Compact 49 4.1.2 Certification Standard: RTRS & Proterra Foundation 51 4.1.3 Targeted Financial Instrument: Soft Commodities Compact -

Sustainable Coffee Certifications a Comparison Matrix

Sustainable Coffee Certifications A Comparison Matrix Created by the SCAA Sustainability Committee (2009) Certification / Organic Fair Trade Rainforest Smithsonian 4 C Utz Certified Verification Certified Alliance Bird Friendly® Common Code Create a verified Support a better life for Integrate biodiversity Conduct research and UTZ CERTIFIED’s Achieve global sustainable agriculture farming families in the conservation, community education around issues mission is to achieve leadership as the system that produces developing world through development, workers’ of neo-tropical migratory sustainable agricultural baseline initiative that food in harmony with fair prices, direct trade, rights and productive bird populations, supply chains, where: enhances economic, nature, supports community development agricultural practices to promoting certified shade Producers are social and environmental biodiversity and and environmental ensure comprehensive coffee as a viable professionals production, processing enhances soil health. stewardship. sustainable farm supplemental habitat for implementing good and trading conditions to management. birds and other practices which enable all who make a living in organisms. better businesses, the coffee sector. livelihoods and Mission environments; The Food industry takes responsibility by demanding and rewarding sustainably grown products; Consumers buy products which meet their standard for social and environmental responsibility. All markets All markets Global, with special All markets Mainstream and Mainstream market emphasis on N. America, Specialty (ambition: vast majority Market Focus Europe, Japan, and of coffee market) Australia Trace back to 19th century Began as Max Havelaar Begun in 1992 by Founded in 1997 with Begun in 1997 as Begun in 2003 as public- practices formulated in in the Netherlands in the Rainforest Alliance and a criteria based on initiative from industry private partnership England, India, and the US. -

The Economics of Biodiversity: the Dasgupta Review

The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Summary brief for Review(2021) business On 2 February, the UK Government Nature is an indispensable system value of a country’s economic launched The Economics of on which we all depend, and which success, is a necessary step Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. must thrive for us to effectively towards returning the world to This independent review was respond to challenges, such as a path of sustainable prosperity commissioned by the UK Treasury those posed by emerging diseases instead of continuing to live beyond to shape the international response including COVID-19 and climate our planet’s means. to biodiversity loss and inform global change. The Dasgupta Review action from all stakeholders. makes clear that conservation and restoration efforts are solutions WANT TO LEARN MORE? The Dasgupta Review sets out to these critical challenges and a new framework, grounded in provide many other benefits to the You can find the Headlines ecology and Earth Sciences, yet economy and society. Not only does Messages of the Dasgupta applying principles from finance the conservation and restoration Review here. The full report can and economics to understand the of nature reduce serious risks to be found here. sustainability of our interaction our economies, including business There is now ample evidence with nature and prioritize efforts and financial institutions, but it also that nature plays a key role to enhance nature and prosperity. contributes towards the mitigation in the COVID-19 pandemic’s of, and adaptation to, the effects of emergence and recovery. In This business summary highlights climate change. -

Chain of Custody Standard

CHAIN OF CUSTODY STANDARD Version 1.1 December 2015 + COCOA ANNEX Version 1.2 January 2018 Copies and translations of this document are available in electronic format on the UTZ website: www.utz.org Or via regular mail to: UTZ Standard and Certification Department De Ruyterkade 6 bg 1013 AA Amsterdam The Netherlands © UTZ 2015 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without full attribution. www.utz.org 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1. What is the Chain of Custody Standard? .......................................................................................... 3 1.2. Why an updated version? ................................................................................................................. 3 1.3. When to comply with the Chain of Custody Standard version 1.1 December 2015 ............................ 4 1.4. Scope of the Chain of Custody Standard .......................................................................................... 4 1.5. Other relevant documents ............................................................................................................... 4 1.6. Labeling and Trademark Policy ........................................................................................................ 5 1.7. Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................. -

A Green New Deal for Europe Towards Green Modernization in the Face of Crisis

A Green New Deal for Europe Towards green modernization in the face of crisis Authors: Dr. Philipp Schepelmann Marten Stock Thorsten Koska Dr. Ralf Schüle Prof. Dr. Oscar Reutter Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy This report was commissioned by: Green New Deal Acknowledgements Special thanks are owed to the four reviewers Prof. Dr. Raimund Bleischwitz, Susanne Böh‐ ler, Prof. Dr. Manfred Fischedick, Prof. Dr. Peter Hennicke, and Dr. Stefan Thomas at the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy. Thanks, too, to Joachim Denkinger and his team for the professional management of a productive dialogue between the au‐ thors and MEPs of the Greens and the European Free Alliance as well as their dedicated staff at the European Parliament. Wuppertal, September 2009 I Green New Deal Foreword We are confronted with the convergence of multiple crises ‐ economic, environment and social, which call for a global response. In the 1930s, President Roosevelt launched his ambi‐ tious "New Deal" to get America out of the Great Depression, crashing markets and soaring unemployment. Today, the crisis is not only economic and can only be fought with an inte‐ grated policy approach: A GREEN NEW DEAL. This has been acknowledged as global chal‐ lenge by the Secretary General of the United Nations, Ban Ki Moon, the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP). Trying to overcome the economic crisis by putting more pressure on the environment is not an option, because global warming and resource depletion already threaten our very exis‐ tence. Overcoming the environmental crisis by putting a halt to economic activity of citizens, risking unemployment and poverty to soar to unprecedented heights, is not an option ei‐ ther.