Language and Migration the Impact of the Jukun on Chadic Speaking Groups in the Benue-Gongola Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015)

Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Nigeria Conflict Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) World Watch Research November, 2015 [email protected] www.theanalytical.org 1 Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Taraba State, Nigeria. Source: NCSAN. The Deeper Reality of the Violent Conflict in Taraba State and the Plight of Christians Nigeria Conflict and Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) Working Paper No. 2, Abuja, Nigeria November, 2015 Authors: Abdulbarkindo Adamu and Alupse Ben Commissioned by World Watch Research, Open Doors International, Netherlands No copyright - This work is the property of World Watch Research (WWR), the research department of Open Doors International. This work may be freely used, and spread, but with acknowledgement of WWR. 2 Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge with gratitude all that granted NCSAN interviews or presented documented evidence on the ongoing killing of Christians in Taraba State. We thank the Catholic Secretariat, Catholic Diocese of Jalingo for their assistance in many respects. We also thank the Chairman of the Muslim Council, Taraba State, for accepting to be interviewed during the process of data collection for this project. We also extend thanks to NKST pastors as well as to pastors of CRCN in Wukari and Ibi axis of Taraba State. Disclaimers Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen: Throughout this paper, the phrase Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen is used to designate those responsible for the attacks against indigenous Christian communities in Taraba State. However, the study is fully aware that in most reports across northern Nigeria, the term Fulani herdsmen is also in use. -

Concentration in the North Eastern Nigeria's Yam Market: a Gini

49 Agro-Science Journal of Tropical Agriculture, Food, Environment and Extension Volume 10 Number 2 May 2011 pp. 49 - 57 ISSN 1119-7455 CONCENTRATION IN THE NORTH EASTERN NIGERIA’S YAM MARKET: A GINI COEFFICIENT ANALYSIS Taru1, V.B., and Lawal2 H. 1Department of Agricultural Technology Federal Polytechnic P.M.B. 35 Mubi Adamawa State Nigeria 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension Moddibo Adama University of Technology P. M. B. 2076 Yola, Adamawa State Nigeria ABSTRACT Policy formulation has failed to take cognizance of the fact that production and marketing constitute a continuum and that the absence of development in one retards progress in the other. The study analysed the concentration of yam markets in southern part of Adamawa and Taraba states. It specifically identified the degree of product differentiation, market information dissemination and determined the concentration of yam sellers in the markets. A total of 410 respondents comprising 210 retailers and 200 wholesalers were randomly sampled using simple random sampling techniques from six purposively selected yam markets namely, Ganye, Nadu and Tola markets in Adamawa State and Wukari, Sarkin-Kudu, and Chanchanjim markets, Taraba State. Descriptive statistics, Gini coefficient and Lorenz Curve were the analytical tools used. The common features used in yam differentiation were yam varieties and size or length and market information were majorly disseminated by means of personal contact (verbal message) and telephone (GSM). The Gini coefficient of 0.56 and 0.52 were obtained for wholesaling and retailing, respectively. The concentration of sales was high with high income inequality in yam wholesaling than retailing in the area. -

The Niger River Basin Avision For

DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT 34518 The Niger Public Disclosure Authorized River Basin AVision for Sustainable Management INGER ANDERSEN, OUSMANE DIONE, MARTHA JAROSEWICH-HOLDER, JEAN-CLAUDE OLIVRY EDITED BY KATHERIN GEORGE GOLITZEN Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BENIN Public Disclosure Authorized The Niger River Basin: A Vision for Sustainable Management The Niger River Basin: A Vision for Sustainable Management Inger Andersen Ousmane Dione Martha Jarosewich-Holder Jean-Claude Olivry Edited by Katherin George Golitzen THE WORLD BANK Washington, DC © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. 123408070605 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Ground Water and River Quality Assessment for Some Heavy Metals and Physicochemical Parameters in Wukari Town, Taraba State, Nigeria M

Ground Water and River Quality Assessment for Some Heavy Metals and Physicochemical Parameters in Wukari Town, Taraba State, Nigeria M. O. Aremu1, O. J. Oko1, C. Andrew1 1Department of Chemical Sciences, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020, Wukari, Taraba State, Nigeria Abstract: With a few to assessing the qualities of water sources in Wukari local government area (LGA), a study was conducted on ground water and rivers in two settlements at Wukari LGA. For this purpose, some heavy metals (cadmium, lead, arsenic, iron, copper, mercury and manganese) and physicochemical parameters (temperature, turbidity, suspended solids, total dissolved solids, conductivity, pH, nitrate, phosphate, chloride, alkalinity, hardness and chemical/biochemical oxygen demand) were determined in water samples collected from hand–dug wells, boreholes and rivers in Puje and Avyi during wet and dry seasons using standard analytical techniques. The results showed that all the seven metals determined were detected and present at trace levels in all the water samples ranging from 0.001 ppm (Hg) in well and borehole to 0.0768 ppm (Fe) in river, and 0.001 ppm (Hg) in borehole to 0.0763 ppm (Fe) in river for Puje and Avyi, respectively. However, all the metals were found to have contained concentrations below the permissible safe level. The results further revealed that the levels of physicochemical parameters in the water samples for both wet and dry seasons are within the required standard limits set by World Health Organization (WHO) for drinking water. Nevertheless, source protection is recommended for the bodies of water for the benefit of Wukari people. Keywords: Hand–dug Well, Borehole, River, Physicochemical Parameter, Wukari Introduction applications, urban runoff, debris from erosion and Water covers more than 70% of the earth though only polluted surface water [4]. -

SEASONAL VARIATION in HYDRO CHEMISTRY of RIVER BENUE at MAKURDI, BENUE STATE NIGERIA Akaahan T

International Journal of Environment and Pollution Research Vol.4, No.3, pp.73-84, July 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) SEASONAL VARIATION IN HYDRO CHEMISTRY OF RIVER BENUE AT MAKURDI, BENUE STATE NIGERIA Akaahan T. J. A1*, Leke L2 and Eneji I.S3 1Department of Biological Sciences University of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2373 Makuedi Benue state Nigeria. 2Department of Chemistry Benue state University P.M.B.102119 Makurdi Benue State Nigeria 3Department of Chemistry, University of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2373 Makuedi Benue state Nigeria. ABSTRACT: The hydrochemistry of River Benue at Makurdi was studied for two years (July 2011-June 2013). Water samples were collected monthly from five different Stations on the shoreline of River Benue at Makurdi. The hydrochemistry of the water samples were examined using standard methods. The results of the physico-chemical parameters indicate the river water samples with the following characteristics: conductivity ranged from 139±215.05µS/cm - 63.95±30.94µS/cm, pH varied from 6.33±0.59-6.95±0.86, TDS varied from 28.29±11.69mg/L- 69.14±106.65mg/L, TSS varied from 41.00±25.42mg/L- 87.56±57.39mg/L, colour ranged from 192.60±143.79TCU-393.01±175.73TCU, turbidity ranged from 44.53±44.28NTU – 91.38±56.54NTU, surface water temperature ranged from 28.09±1.970C – 28.99±1.630C, bicarbonate ranged from 121.98±59.13mg/L – 185.61±57.20mg/L, chloride ranged from 117.44±59.46mg/L – 173.07±71.27mg/L, nitrate ranged from 2.23±3.14mg/L – 3.76±5.22mg/L, sulphate ranged from 10.41±9.84mg/L- 17.24±15.21mg/L, phosphate ranged from 0.92±1.11mg/L- 1.47±2.07mg/L and copper ranged from 0.11±0.09mg/L- 0.31±0.34mg/L. -

The Structure of Road Network Connectivity In

International Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Research Vol.5, No.1, pp.1-14, April 2020 Published by ECRTD- UK Print ISSN: 2059-2418 (Print), Online ISSN: 2059-2426 (Online) STRUCTURE OF ROAD NETWORK CONNECTIVITY IN THE BENUE BASIN OF NIGERIA Daniel P. DAM1; Davidson ALACI2; Vesta Udoo3; Jacob ATSER4 ; Fanan UJOH5 & Timothy GYUSE6 1Department of Geography Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Benue State University, Makurdi-Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Jos-Nigeria 3Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Benue State University, Makurdi-Nigeria. 4Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Uyo-Nigeria 5Centre for Sustainability and Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, London South Bank University, UK 6Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Nasarawa State University, Keffi-Nigeria Corresponding Author: Daniel P. Dam, [email protected] ABSTRACT: The structure of road network connectivity in any region can either promote or reduce agricultural production, market opportunities, cultural and social interactions as well as businesses and employment opportunities. This study evaluates road network connectivity in the Benue Basin of Nigeria. Data on the existing road network including type and conditions, density and length of the roads in the study area were extracted from existing road map of Nigeria, and satellite imagery of the Benue basin. The data was analysed using different methods of network connectivity analysis including beta index, alpha and gamma indices. The findings reveal four types of roads network in the basin which are grouped into three categories namely: federal highways (trunk A), state government roads (trunk B) and local government and community roads (trunk C) which are in various state of deplorable conditions. -

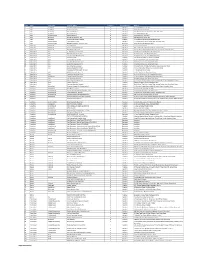

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Patterns of Migration and Population Mobility in Sudanic West Africa: Evidence from Ancient Kano, C

Afrika Zamani, No. 24, 2016, pp. 11-30 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa & Association of African Historians 2017 (ISSN 0850-3079) Patterns of Migration and Population Mobility in Sudanic West Africa: Evidence from Ancient Kano, c. 800–1800 AD Akachi Odoemene* Abstract In the last three decades historians of migration in Europe and the Americas have increasingly criticised the idea of a ‘mobility transition’, which assumed that pre- modern societies were geographically fairly immobile, and that people only started to move in unprecedented ways from the nineteenth century onwards. This paper takes this perspective as a point of departure, and further presents evidence of remarkable population mobility from ancient Kano, taking a longue durée viewpoint. It reconstructs the nature and transformative roles of constant and consistent migration and population mobility in Kano, which ensured enormous social interactions within and between culturally distinct communities and led to socio-cultural changes. This earned Kano a reputation as an important, formidable and large medieval urban metropolis in Western Sudan. Thus, ancient Kano, like elsewhere in Sudanic Africa, had a rich history of massive and systematic migration and population mobility since the ninth century AD. Résumé Au cours des trois dernières décennies, les historiens de la migration en Europe et dans les Amériques ont de plus en plus critiqué l’idée d’une « transition de la mobilité », qui supposait que les sociétés prémodernes étaient géographiquement assez immobiles et que les populations n’ont commencé à se déplacer de manière inédite qu’à partir du dix-neuvième siècle. Partant de ce point de vue, le présent article présente des éléments attestant de la remarquable mobilité démographique dans l’ancienne Kano, sous une perspective de longue durée. -

Geospatial Analysis of Flood Problems in Jimeta Riverine Community of Adamawa State, Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol.5, No.12, 2015 Geospatial Analysis of Flood Problems in Jimeta Riverine Community of Adamawa State, Nigeria Innocent E. Bello 1* Steve O. Ogedegbe 2 1. MP, IT and Data Management Dept., National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA), Obasanjo Space Centre, Airport Road, PMB 437 Garki, Abuja, Nigeria. 2. Department of Geography, College of Education, Igueben, Edo State, Nigeria Abstract Floods are among the most devastating natural disasters in the world, claiming more lives and causing more property damages than any other natural phenomena. In recent times, the incidence of flooding across Nigeria has left both the government and the governed devastated. It is no longer news that flooding and its attendant consequences are injurious to man while the spatial dimensions are often not mapped. This study, therefore, examined the nature of water level/extent and vulnerability in the riverine community of Jimeta, Adamawa State. Using time series analysis, four epoch satellite images covering the study area was used to evaluate the geospatial coverage of water along the watercourse of Upper Benue bordering the study area. Using ILWIS 3.8, ArcGIS 10.1 and statistical analysis, the spatial extent and vulnerability of settlements was mapped. Highly vulnerable (50m buffer) were differentiated from low risk zones (100m buffers). Study revealed that besides rainfall, excess water from Cameroun dam is largely responsible for the identified high level of inundation. -

An Assessment of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Nigerian Society: the Examples of Banking and Communication Industries

Universal Journal of Marketing and Business Research Vol. 1(1) pp. 017-043, May, 2012 Available online http://www.universalresearchjournals.org/ujmbr Copyright © 2012 Transnational Research Journals Full Length Research Paper An assessment of the impact of corporate social responsibility on Nigerian society: The examples of banking and communication industries Adeyanju, Olanrewaju David Department of Financial Studies Redeemer’s University, km 46, Lagos Ibadan Expressway Mowe, Ogun State E-mail: [email protected], Tel No.: 07037794073 Accepted 30 January, 2012 In the Nigerian society, Corporate Social Responsibilities [CSR] has been a highly cotemporary and contextual issue to all stakeholders including the government, the corporate organization itself, and the general public. The public contended that the payment of taxes and the fulfillment of other civic rights are enough grounds to have the liberty to take back from the society in terms of CSR undertaken by other stakeholders. Some ten year ago, what characterized the Nigerian society was fragrant pollution of the air, of the water and of the environment. Most corporate organizations are concerned about what they can take out of the society, and de-emphasized the need to give back to the society [their host communities]. This attitude often renders the entire community uninhabitable. A case in mind is the Niger Delta area of Nigeria. This translated to negative integrity and reputation on the part of corporate identity as people perceived this as exploitation and greed for profitability and wealth maximization within a decaying economy of Nigeria. However, the general belief is that both business and society gain when firms actively strive to be socially responsible; that is, the business organizations gain in enhanced reputation, while society gains from the social projects executed by the business organization. -

Organised by The

Organised by the Held at Nicon Hilton Hotel, Abuja 14th-15th May, 2002 DFID' - -'.'~ REPORT OF THE NATIONAL . WORKSHOP OF STAKEHOLDERS OF'PEACE RESEARCH AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION Organised by the Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR) Held at Nicon Hilton Hotel, Abuja, Nigeria 14th -15th May, 2002 In collaboration .with: UND~ THE WORLD BANK, DFID and USAID Prepared by: Dr Johnson Bade Falade, Programme Analyst, Governance & Management of Development Unit, UNDp, Lagos © Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR) ISBN 978-34023-7-4 FOREWORD It gives Ine a great pleasure to write the foreword to this publication, which puts on record a ll1ajor contribution of the Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, an establishInent/administer on behalfof Governnlent. It is a fact that without a modicunl of peace in any society developnlent would be an illusion. Although the IP(1\ is Government's apex establishnlent in the systenlatic pursuit and building of pellce, it realized early enough that the pursuit of conflict resolution and maintaining a culture of peace Cilnnot be dictated by fiat. To achieve appreciable success in either venture needs full collabori.1tion with a galnut of players, which we refer to as stakeholders. Non Governmental Orgi:lnisiltions, COll1nlunity-Based Organisations, research and advocacy institutions in the areas of peace research, peace-building, and conflict resolution need to be cultivated so that the collective and nlany-pronged further efforts that would ensued can have a chance of ta king form root anlong civil society and bear peace dividends. One Inajor role of the IPCR is to provide a bridge between Governnlent and the civil society to prOlnote a culture of peace. -

Igala's Royal Masks

Igala’s Royal Masks Borrowed, Invented, or Stolen? Sidney Littlefield Kasfir all photos by the author except where otherwise noted n contrast to the numerous small-scale gerontocracies 1979, 2011: 37–39). Here I will cut that argument short and simply found in the area we now know as eastern Nigeria, a state that, despite all the cultural similarities, there is an Igala lan- strong centralized kingship grew up (or was imposed) guage (which is more closely cognate with Yoruba than Idoma), sometime before the sixteenth century near the Niger- there is an Idoma language (also cognate with Igala), and there is Benue Confluence, nexus of north-south and east-west no Akpoto language, suggesting that the label applied to the entire riverine trade. Its present identity as “the Igala kingdom” region, “Akpoto,” is another name for “unknown territory” on the glosses over a complex historical entity that has shifting claims of part of nineteenth century writers. Later, the British administra- originI among several regional powers over the centuries (Fig. 1). tion came to realize that nearly all of the Idoma-speaking lands Spatially, it is contiguous with Igbo/Ibaji settlements to the south (aje) demonstrated close historical ties with the Jukun and the fed- and western Idoma settlements to the east. Both of these connec- eration of early states known as Apá or the Hausa term Kwararafa. tions are highly visible in Igala masquerade culture. Beyond that, The term “Akpoto came to represent the “indigenous people” who Igala oral histories allege important historical ties to Yoruba, Benin, predated the arrival of newcomers following the breakup of the and Apá/Kwararafa political formations that also figure in Igala Apá federation in the early seventeenth century and the population political and visual culture (Clifford 1936, Murray 1949, Boston shifts it caused among the twenty-odd Idoma-speaking lands.