Classic Film Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Šta Znače Oznake CAM, WP, TS, SCR, TC, R5, DVDRIP, HDTV?

Šta znače oznake CAM, WP, TS, SCR, TC, R5, DVDRIP, HDTV? Ako vas zanima šta tačno označavaju skraćenice za kvalitet filmskog snimka: CAM, WP, TS, SCR, TC, R5, DVDRIP, HDTV, itd., pročitajte ovaj članak. Slijedi tabela kvaliteta filmskih snimaka, koja govori sa kog fizickog medija (kino snimak kamerom, original vhs kaseta, original dvd, itd) je film kopiran, u smjeru od najlošijeg kvaliteta ka najboljem. Tip Oznaka Rasprostranjenost Dosta čest format, mada se sve ređe Cam "CAM" pojavljuje, zbog postojanja DVD rip formata koji je daleko kvalitetniji Snimak filma napravljen kamerom u kinu, a zvuk je dobijen pomoću mikrofona na kameri, tako da se često vide i čuju i gledaoci u bioskopu. Ovaj kvalitet snimka se obično pojavi odmah nakon prve premijere filma u kinima Kvalitet video i audio zapisa je najčešće veoma loš. "WP" Workprint Vrlo rijedak "WORKPRINT" Kopija napravljena od nedovršene verzije filma. Uglavnom fale mnogi efekti i film može da se skroz razlikuje od konačne verzije filma. "TS" Telesync Vrlo čest "TELESYNC" Nasuprot popularnom vjerovanju, kvalitet kod TS video snimka ne mora da bude bolji od kvaliteta CAM snimka. Naziv Telesync ne označava bolji kvalitet VIDEO zapisa, nego bolji kvalitet AUDIO zapisa. Uglavnom je video snimak isti kao i CAM, a audio snimak bolji. Zbog toga se CAM veoma često brka sa TS. R5 "R5" Vrlo čest R5 Line je DVD verzija za region 5. Region 5 čine Istočna Evropa, (bivši SSSR), Indija, Afrika, Severna Koreja i Mongolija. Kvalitet R5 snimka se razlikuje od kvaliteta normalnog DVD-a po tome što je video snimak odličnog kvaliteta (kopiran sa DVD-a), a audio snimak je lošeg kvaliteta (kopiran sa Telecyne snimka, da bi se dobio zvuk originala, pošto je R5 DVD verzija obično prilagođena/sinhronizovana na jezik nekog od tih 5 regiona). -

Tisch School of the Arts

18 Visible TISCH SCHOOL New York University EOFvidence THE ARTS August 11-14, 2011 NEW YORK, WELCOME EVER VIGILANT, IS THE CITY THAT never sleeps, a perfect setting for an international TO YOU ALL! conference on documentary film. We extend our thanks to Tisch School of the Arts, Cinema Studies Pro- WITHIN THE BROADER CONTEXT fessor, and Visible Evidence 18 Conference Director, Jon- of our Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program athan Kahana for his energetic efforts to bring the confer- and Certificate Program in Culture and Media, the De- ence to the Big Apple. Professor Kahana has deployed his superb organizational skills to assemble an impressive set of partment of Cinema Studies at NYU is committed to sponsoring institutions and panelists over the four days of the developing both pedagogy and practice in the field conference and we are grateful to him and the legion of vol- of documentary. The fact that this year we are unteers and participating institutions who made hosting Visible Evidence 18 is a demonstra- this event possible. The Visible Evidence 18 Con- ference is a bittersweet occasion: we celebrate a tion of that commitment as well as a validation, great filmmaker, the “dean” of documentary film, as Jonathan Kahana writes, of documentary film-mak- George Stoney, Professor Emeritus in the Tisch ers’ long love affair with New York. I want to congratulate School’s Kanbar Institute of Film and Television, Professor Kahana for putting together this stellar conference and we pay tribute to our school’s beloved and renowned theorist and historian, the late Rob- and mobilizing such a wide range of institutional collabora- ert Sklar, Professor Emeritus in the department tors across the city. -

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films Harlean Harlow Carpenter - later Jean Harlow - was born in Kansas City, Missouri on 3 March 1911. After being signed by director Howard Hughes, Harlow's first major appearance was in Hell's Angels (1930), followed by a series of critically unsuccessful films, before signing with Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer in 1932. Harlow became a leading lady for MGM, starring in a string of hit films including Red Dust (1932), Dinner At Eight (1933), Reckless (1935) and Suzy (1936). Among her frequent co-stars were William Powell, Spencer Tracy and, in six films, Clark Gable. Harlow's popularity rivalled and soon surpassed that of her MGM colleagues Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer. By the late 1930s she had become one of the biggest movie stars in the world, often nicknamed "The Blonde Bombshell" and "The Platinum Blonde" and popular for her "Laughing Vamp" movie persona. She died of uraemic poisoning on 7 June 1937, at the age of 26, during the filming of Saratoga. The film was completed using doubles and released a little over a month after Harlow's death. In her brief life she married and lost three husbands (two divorces, one suicide) and chalked up 22 feature film credits (plus another 21 short / bit-part non-credits, including Chaplin's City Lights). The American Film Institute (damning with faint praise?) ranked her the 22nd greatest female star in Hollywood history. LIBERTY, BACON GRABBERS and NEW YORK NIGHTS (all 1929) (1) Liberty (2) Bacon Grabbers (3) New York Nights (Harlow left-screen) A lucky few aspiring actresses seem to take the giant step from obscurity to the big time in a single bound - Lauren Bacall may be the best example of that - but for many more the road to recognition and riches is long and grinding. -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

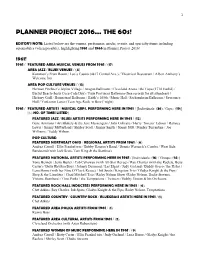

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 60S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 60s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting 1961 and 1966 in Planner Project 2016! 1961! 1961 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1961 / (17) AREA JAZZ / BLUES VENUES / (4) Kornman’s Front Room / Leo’s Casino (4817 Central Ave.) / Theatrical Restaurant / Albert Anthony’s Welcome Inn AREA POP CULTURE VENUES / (13) Herman Pirchner’s Alpine Village / Aragon Ballroom / Cleveland Arena / the Copa (1710 Euclid) / Euclid Beach (hosts Coca-Cola Day) / Four Provinces Ballroom (free records for all attendees) / Hickory Grill / Homestead Ballroom / Keith’s 105th / Music Hall / Sachsenheim Ballroom / Severance Hall / Yorktown Lanes (Teen Age Rock ‘n Bowl’ night) 1961 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GRPS. PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (36) / Grps.: (19)] [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED JAZZ / BLUES ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / (12) Gene Ammons / Art Blakely & the Jazz Messengers / John Coltrane / Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison / Ramsey Lewis / Jimmy McPartland / Shirley Scott / Jimmy Smith / Sonny Stitt / Stanley Turrentine / Joe Williams / Teddy Wilson POP CULTURE: FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1961 / (6) Andrea Carroll / Ellie Frankel trio / Bobby Hanson’s Band / Dennis Warnock’s Combo / West Side Bandstand (with Jack Scott, Tom King & the Starfires) FEATURED NATIONAL ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (16) / Groups: (14)] Tony Bennett / Jerry Butler / Cab Calloway (with All-Star -

November 2019

MOVIES A TO Z NOVEMBER 2019 D 8 1/2 (1963) 11/13 P u Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons (1960) 11/21 o A Day in the Death of Donny B. (1969) 11/8 a ADVENTURE z 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) 11/5 S Ho Booked for Safekeeping (1960) 11/1 u Dead Ringer (1964) 11/26 S 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 11/27 P D Bordertown (1935) 11/12 S D Death Watch (1945) 11/16 c COMEDY c Boys’ Night Out (1962) 11/17 D Deception (1946) 11/19 S –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– z Breathless (1960) 11/13 P D Dinky (1935) 11/22 z CRIME c Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) 11/1 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 11/16 w The Dirty Dozen (1967) 11/11 a Adventures of Don Juan (1948) 11/18 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 11/6 P D Dive Bomber (1941) 11/11 o DOCUMENTARY a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 11/8 R Brief Encounter (1945) 11/15 Doctor X (1932) 11/25 Hz Alibi Racket (1935) 11/30 m Broadway Gondolier (1935) 11/14 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 11/20 P D DRAMA c Alice Adams (1935) 11/24 D Bureau of Missing Persons (1933) 11/5 S y Dodge City (1939) 11/8 c Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More (1974) 11/10 w Burn! (1969) 11/30 z Dog Day Afternoon (1975) 11/16 e EPIC D All About Eve (1950) 11/26 S m Bye Bye Birdie (1963) 11/9 z The Doorway to Hell (1930) 11/7 S P R All This, and Heaven Too (1940) 11/12 c Dr. -

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The

A Framework for Application Specific Knowledge Engines Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Lai, Guanpi Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 03:58:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/204290 A FRAMEWORK FOR APPLICATION SPECIFIC KNOWLEDGE ENGINES by Guanpi Lai _____________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SYSTEMS AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Guanpi Lai entitled A Framework for Application Specific Knowledge Engines and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/28/2010 Fei-Yue Wang _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/28/2010 Ferenc Szidarovszky _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/28/2010 Jian Liu Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent -

October 13 - 19, 2019

OCTOBER 13 - 19, 2019 staradvertiser.com HIP-HOP HISTORY Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson and Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter discuss the origins and impact of iconic hip-hop anthems in the new six-part docuseries Hip Hop: The Songs That Shook America. The series debut takes a look at Kanye West’s “Jesus Walks,” a Christian rap song that challenged religion. Premiering Sunday, Oct. 13, on AMC. Join host, Lyla Berg as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW EPISODE! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Rosalyn K.R.D. Concepcion, KiaҊi Loko AlakaҊi Pond Manager, Waikalua Loko IҊa that make 1st & 3rd Kevin P. Henry, Regional Communications Manager, Red Cross of HawaiҊi Hawai‘i Wednesday of the Month, Matt Claybaugh, PhD, President & CEO, Marimed Foundation 6:30 pm | Channel 53 olelo.org special. Greg Tjapkes, Executive Director, Coalition for a Drug-Free Hawaii ON THE COVER | HIP HOP: THE SONGS THAT SHOOK AMERICA Soundtrack of a revolution ‘Hip Hop: The Songs That “Hip-hop was seen as a low-level art form, or BlackLivesMatter movement. Rapper Pharrell Shook America’ airs on AMC not even seen as actual art,” Questlove said. Williams, the song’s co-producer, talked about “People now see there’s value in hip-hop, but I the importance of tracing hip-hop’s history in feel like that’s based on the millions of dollars a teaser for “Hip Hop: The Songs That Shook By Kyla Brewer it’s generated. Like its value is like that of junk America” posted on YouTube this past May. -

Steven Spielberg's Early Career As a Television Director at Universal Studios

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Surugadai University Academic Information Repository Steven Spielberg's Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios 著者名(英) Tomohiro Shimahara journal or 駿河台大学論叢 publication title number 51 page range 47-61 year 2016-01 URL http://doi.org/10.15004/00001463 Steven Spielberg’s Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios SHIMAHARA Tomohiro Introduction Steven Spielberg (1946-) is one of the greatest movie directors and producers in the history of motion picture. In his four-decade career, Spielberg has been admired for making blockbusters such as Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), E.T.: the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Indiana Jones series (1981, 1984, 1989, 2008), Schindler’s List (1993), Jurassic Park series (1993, 1997, 2001, 2015), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Lincoln (2012) and many other smash hits. Spielberg’s life as a filmmaker has been so brilliant that it looks like no one believes that there was any moment he spent at the bottom of the ladder in the movie industry. Much to the surprise of the skeptics, Spielberg was once just another director at Universal Television for the first couple years after launching himself into the cinema making world. Learning how to make good movies by trial and error, Spielberg made a breakthrough with his second feature-length telefilm Duel (1971) at the age of 25 and advanced into the big screen, where he would direct and produce more than 100 movies, including many great hits and some commercial or critical failures, in the next 40-something years. -

The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde by David Edmondson

The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde By David Edmondson D-LAB FILMS First Draft July 2012 Second Draft August 2012 Third Draft August 2012 EXT. TEXAS HIGHWAY--NIGHT Pitch black night broken by the headlight of a 1932 Ford V8 Coupe screaming down a secluded Texas highway. INT. FORD--CONTINUED Three people are crammed into the small Ford along with an arsenal. In the back seat W.D. JONES (17) he is curled asleep on the back bench. In the front seat BONNIE PARKER (22) is asleep on the shoulder of her lover CLYDE BARROW (23) who is driving at near light speed. The Ford’s headlights dimly light the road making it truly hard to see what is out there. Clyde passes a bridge out sign. Suddenly... EXT. BRIDGE--CONTINUED the Ford crashes through the road block--it instantly launched into the air. It comes smashing down rolling three times--the Ford is destroyed but standing upright. The Ford’s fuel line has become split--it is leaking fuel. The cable has come loose from the battery. All three passengers are knocked out. Clyde first to awake gets out of the car--blood running down his nose. He stumbles around trying to gain conciseness. He pulls W.D. out from the wreckage--returning to get Bonnie next. W.D. awakens--he is at Clyde’s side helping to pull Bonnie from the car. Then... a spark from the loose battery cord starts a fire. Flames begin to cover the hood. W.D. starts to kick dirt on the fire--it doesn’t help. -

Nimal Dunuhinga - Poems

Poetry Series nimal dunuhinga - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive nimal dunuhinga(19, April,1951) I was a Seafarer for 15 years, presently wife & myself are residing in the USA and seek a political asylum. I have two daughters, the eldest lives in Austalia and the youngest reside in Massachusettes with her husband and grand son Siluna.I am a free lance of all I must indebted to for opening the gates to this global stage of poets. Finally, I must thank them all, my beloved wife Manel, daughters Tharindu & Thilini, son-in-laws Kelum & Chinthaka, my loving brother Lalith who taught me to read & write and lot of things about the fading the loved ones supply me ingredients to enrich this life's bitter-cake.I am not a scholar, just a sailor, but I learned few things from the last I found Man is not belongs to anybody, any race or to any religion, an independant-nondescript heaviest burden who carries is the Brain. Conclusion, I guess most of my poems, the concepts based on the essence of Buddhist personal belief is the Buddha who was the greatest poet on this planet earth.I always grateful and admire him. My humble regards to all the readers. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 * I Was Born By The River My scholar friend keeps his late Grandma's diary And a certain page was highlighted in the color of yellow. My old ferryman you never realized that how I deeply loved you? Since in the cradle the word 'depth' I heard several occasions from my parents.