Darwin's Lost World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ediacaran Frondose Fossil Arborea from the Shibantan Limestone of South China

Journal of Paleontology, 94(6), 2020, p. 1034–1050 Copyright © 2020, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2020.43 The Ediacaran frondose fossil Arborea from the Shibantan limestone of South China Xiaopeng Wang,1,3 Ke Pang,1,4* Zhe Chen,1,4* Bin Wan,1,4 Shuhai Xiao,2 Chuanming Zhou,1,4 and Xunlai Yuan1,4,5 1State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Palaeoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China <[email protected]><[email protected]> <[email protected]><[email protected]><[email protected]><[email protected]> 2Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061, USA <[email protected]> 3University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 5Center for Research and Education on Biological Evolution and Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China Abstract.—Bituminous limestone of the Ediacaran Shibantan Member of the Dengying Formation (551–539 Ma) in the Yangtze Gorges area contains a rare carbonate-hosted Ediacara-type macrofossil assemblage. This assemblage is domi- nated by the tubular fossil Wutubus Chen et al., 2014 and discoidal fossils, e.g., Hiemalora Fedonkin, 1982 and Aspidella Billings, 1872, but frondose organisms such as Charnia Ford, 1958, Rangea Gürich, 1929, and Arborea Glaessner and Wade, 1966 are also present. -

Geochemistry This

TORONTOTORONTO Vol. 8, No. 4 April 1998 Call for Papers GSA TODAY — page C1 A Publication of the Geological Society of America Electronic Abstracts Submission — page C3 Antarctic Neogene Landscapes—In the 1998 Registration Refrigerator or in the Deep Freeze? Annual Issue Meeting — June GSA Today Introduction The present Molly F. Miller, Department of Geology, Box 117-B, Vanderbilt Antarctic landscape undergoes very University, Nashville, TN 37235, [email protected] slow environmental change because it is almost entirely covered by a thick, slow-moving ice sheet and thus effectively locked in a Mark C. G. Mabin, Department of Tropical Environmental Studies deep freeze. The ice sheet–landscape system is essentially stable, and Geography, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia, [email protected] Antarctic—Introduction continued on p. 2 Atmospheric Transport of Diatoms in the Antarctic Sirius Group: Pliocene Deep Freeze Arjen P. Stroeven, Department of Quaternary Research, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden Lloyd H. Burckle, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964 Johan Kleman, Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University, S-106, 91 Stockholm, Sweden Michael L. Prentice, Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824 INTRODUCTION How did young diatoms (including some with ranges from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene) get into the Sirius Group on the slopes of the Transantarctic Mountains? Dynamicists argue for emplacement by a wet-based ice sheet that advanced across East Antarctica and the Transantarctic Mountains after flooding of interior basins by relatively warm marine waters [2 to 5 °C according to Webb and Harwood (1991)]. -

Ediacaran) of Earth – Nature’S Experiments

The Early Animals (Ediacaran) of Earth – Nature’s Experiments Donald Baumgartner Medical Entomologist, Biologist, and Fossil Enthusiast Presentation before Chicago Rocks and Mineral Society May 10, 2014 Illinois Famous for Pennsylvanian Fossils 3 In the Beginning: The Big Bang . Earth formed 4.6 billion years ago Fossil Record Order 95% of higher taxa: Random plant divisions domains & kingdoms Cambrian Atdabanian Fauna Vendian Tommotian Fauna Ediacaran Fauna protists Proterozoic algae McConnell (Baptist)College Pre C - Fossil Order Archaean bacteria Source: Truett Kurt Wise The First Cells . 3.8 billion years ago, oxygen levels in atmosphere and seas were low • Early prokaryotic cells probably were anaerobic • Stromatolites . Divergence separated bacteria from ancestors of archaeans and eukaryotes Stromatolites Dominated the Earth Stromatolites of cyanobacteria ruled the Earth from 3.8 b.y. to 600 m. [2.5 b.y.]. Believed that Earth glaciations are correlated with great demise of stromatolites world-wide. 8 The Oxygen Atmosphere . Cyanobacteria evolved an oxygen-releasing, noncyclic pathway of photosynthesis • Changed Earth’s atmosphere . Increased oxygen favored aerobic respiration Early Multi-Cellular Life Was Born Eosphaera & Kakabekia at 2 b.y in Canada Gunflint Chert 11 Earliest Multi-Cellular Metazoan Life (1) Alga Eukaryote Grypania of MI at 1.85 b.y. MI fossil outcrop 12 Earliest Multi-Cellular Metazoan Life (2) Beads Horodyskia of MT and Aust. at 1.5 b.y. thought to be algae 13 Source: Fedonkin et al. 2007 Rise of Animals Tappania Fungus at 1.5 b.y Described now from China, Russia, Canada, India, & Australia 14 Earliest Multi-Cellular Metazoan Animals (3) Worm-like Parmia of N.E. -

Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and Closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams

READING GROUP GUIDE Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams Enter the terrifying world of Tunnels—a subterranean society under the streets of modern London, whose citizens are enslaved by a strange, cruel sect, the Styx, who plan to exterminate all Topsoilers. Can fourteen-year-old Will defeat the Styx, and rescue his missing father? Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams first met at college in London and have remained friends ever since. Gordon, a former investment banker, now lives with his wife and children in Norfolk, England; Williams, an installation artist, inhabits the city’s Hackney neighborhood, accompanied everywhere by his invisible dog. About their writing process, Gordon says: “When I lived in London, my house was only a ten-minute bike ride from where Brian lived, so he’d cycle round and we would work on Tunnels at my kitchen table. When I moved with my family to the country, we discussed Deeper over many late-night phone calls, and swapped sections by email. When I visit London we go to a couple of favorite cafés. They’ve gotten used to us and know that we can make a cup of coffee last several hours!” Tunnels A New York Times Bestseller About the book He’s a loner at school, his sister’s beyond bossy, and his mother watches TV all day long, but at least Will Burrows shares one hobby with his otherwise weird father: They’re both obsessed with archeological sites. When the two discover an abandoned tunnel buried below modern London, they think they’re on the brink of a major find. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

001-012 Primeras Páginas

PUBLICACIONES DEL INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO. Nº 9 ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES planeta tierra Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and Ciencias de la Tierra para la Sociedad D. García-Bellido 9 788478 407590 MINISTERIO MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN E INNOVACIÓN ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido Instituto Geológico y Minero de España Madrid, 2008 Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO, Nº 9 INTERNATIONAL TRILOBITE CONFERENCE (4. 2008. Toledo) Advances in trilobite research: Fourth International Trilobite Conference, Toledo, June,16-24, 2008 / I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido, eds.- Madrid: Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 2008. 448 pgs; ils; 24 cm .- (Cuadernos del Museo Geominero; 9) ISBN 978-84-7840-759-0 1. Fauna trilobites. 2. Congreso. I. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, ed. II. Rábano,I., ed. III Gozalo, R., ed. IV. García-Bellido, D., ed. 562 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. References to this volume: It is suggested that either of the following alternatives should be used for future bibliographic references to the whole or part of this volume: Rábano, I., Gozalo, R. and García-Bellido, D. (eds.) 2008. Advances in trilobite research. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 9. -

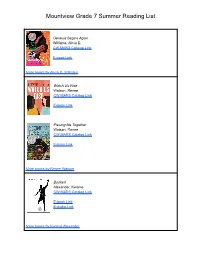

Mountview Grade 7 Summer Reading List

Mountview Grade 7 Summer Reading List Genesis Begins Again Williams, Alicia D. CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Alicia D. Williams Watch Us Rise Watson, Renee CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Piecing Me Together Watson, Renee CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Renee Watson Booked Alexander, Kwame CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link E-audio Link More books by Kwame Alexander Harbor Me Woodson, Jacqueline CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link E-audio Link More books by Jacqueline Woodson Shipwreck at the Bottom of the World Armstrong, Jennifer CW MARS Catalog Link E-audio Link More books by Jennifer Armstrong Tiger, Tiger Banks, Lynn Reis CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Lynn Reis Banks Black Potatoes: the story of the great irish famine Bartoletti, Susan CW MARS Catalog Link More books by Susan Bartoletti Let me Play: the story of Title IX Blumenthal, Karen CW MARS Catalog Link More books by Karen Blumenthal I’d Tell you I Love you, but then I’d have to Kill you (Gallagher Girls, Book 1) Carter, Ally CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: Cross my Heart and Hope to Spy (Gallagher Girls, Book 2) ● E-book Don’t Judge a Girl by her Cover (Gallagher Girls, Book 3) ● E-book Only the Good Spy Young (Gallagher Girls, Book 4) ● E-book Out of Sight, Out of Time (Gallagher Girls, Book 5) ● E-book United we Spy (Gallagher Girls, Book 6) ● E-book More books by Ally Carter The Red Kayak Cummings, Priscilla CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: The Journey Back ● E-book Cheating for the Chicken Man ● E-book More books by Priscilla Cummings The Fire Within (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 1) D'Lacey, Chris CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: Icefire (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 2) ● E-book Firestar (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 3) The Fire Eternal (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 4) Dark Fire (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 5) Fire World (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 6) The Fire Ascending (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 7) More books by Chris D’Lacey Guinea Pig Scientists Dendy, Leslie A. -

WS Folk Riot Booklet

1 playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential Meanwhile, due to our leftist leanings and omni- 10,000 Watts of Folk as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” presence in the Village, activist Abbie Hoffman 1. I AIN’T KISSING YOU (0:54) by Trixie A. Balm met with we three Squares and co-wrote a theme VANGUARD STUDIOS, NYC (aka Lauren Agnelli) Alas, that deal fell through. though the song for his new live radio show, “Radio Free September 1985 sessions remain, with Tom, Lauren, Bruce and Billy U.S.A.”: heard here for the first time since the playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential debut show back in 1986 at the Village Gate. By 1985, we Washington Squares, having worked, as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” Vanguard, an important folk label during the ‘50s sang and played our way through the ‘80’s Richard Hell’s “Love Comes in Spurts,” Lou Reed’s At last, in 1987, Gold Castle/Polydor records who and ‘60s was sold in 1985. Vanguard sold off their Greenwich Village folk scene fray, were ready to “Sweet Jane,” and Johnny Thunders’ “Chinese Rocks.” DID sign us to a deal found the perfect sound classical collection and reissued their folk and then record. The record company interest was there though producer Mitch Easter (of the group Let’s started looking for new acts. With a bunch of well and soon serious recording contracts would dangle Having somewhat mastered those formative nuggets, Active— he also recorded REM’s initial sessions) known original Vanguard producers in the control room: before our fresh (very fresh!) young smirks. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Olenellina Walcott, 1890 (Trilobita, Cambrian) Bruce S

2 j&o I J. Paleont., 75(1), 2001, pp. 96-115 Copyright © 2001, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/01 /0075-96$03.00 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE OLENELLINA WALCOTT, 1890 (TRILOBITA, CAMBRIAN) BRUCE S. LIEBERMAN Departments of Geology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lindley Hall, Lawrence 66045, <[email protected]> ABSTRACT—Phylogenetic analysis was used to evaluate evolutionary relationships within the Cambrian suborder Olenellina Walcott, 1890; special emphasis was placed on those taxa outside of the Olenelloidea. Fifty-seven exoskeletal characters were coded for 24 taxa within the Olenellina and two outgroups referable to the "fallotaspidoid" grade. The Olenelloidea, along with the genus Gabriellus Fritz, 1992, are the sister group of the Judomioidea Repina, 1979. The "Nevadioidea" Hupe, 1953 are a paraphyletic grade group. Four new genera are recognized, Plesionevadia, Cambroinyoella, Callavalonia, and Sdzuyomia, and three new species are described, Nevadia fritzi, Cirquella nelsoni, and Cambroinyoella wallacei. Phylogenetic parsimony analysis is also used to make predictions about the ancestral morphology of the Olenellina. This morphology most resembles the morphology found in Plesionevadia and Pseudoju- domia Egorova in Goryanskii and Egorova, 1964. INTRODUCTION group including the "fallotaspidoids" plus the Redlichiina, and HE ANALYSIS of evolutionary patterns during the Early Cam- potentially all other trilobites. Where the Agnostida fit within this T brian has relevance to paleontologists and evolutionary bi- evolutionary topology depends on whether or not one accepts the ologists for several reasons. Chief among these are expanding our arguments of either Fortey and Whittington (1989), Fortey (1990), knowledge of evolutionary mechanisms and topologies. Regard- and Fortey and Theron (1994) or Ramskold and Edgecombe ing evolutionary mechanisms, because the Cambrian radiation (1991). -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 53, NUMBER 6 CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY No. 6.-0LENELLUS AND OTHER GENERA OF THE MESONACID/E With Twenty-Two Plates CHARLES D. WALCOTT (Publication 1934) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION AUGUST 12, 1910 Zl^i £orb (gaitimovt (pnee BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY No. 6.—OLENELLUS AND OTHER GENERA OF THE MESONACID^ By CHARLES D. WALCOTT (With Twenty-Two Plates) CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 233 Future work 234 Acknowledgments 234 Order Opisthoparia Beecher 235 Family Mesonacidas Walcott 236 Observations—Development 236 Cephalon 236 Eye 239 Facial sutures 242 Anterior glabellar lobe 242 Hypostoma 243 Thorax 244 Nevadia stage 244 Mesonacis stage 244 Elliptocephala stage 244 Holmia stage 244 Piedeumias stage 245 Olenellus stage 245 Peachella 245 Olenelloides ; 245 Pygidium 245 Delimitation of genera 246 Nevadia 246 Mesonacis 246 Elliptocephala 247 Callavia 247 Holmia 247 Wanneria 248 P.'edeumias 248 Olenellus 248 Peachella 248 Olenelloides 248 Development of Mesonacidas 249 Mesonacidas and Paradoxinas 250 Stratigraphic position of the genera and species 250 Abrupt appearance of the Mesonacidse 252 Geographic distribution 252 Transition from the Mesonacidse to the Paradoxinse 253 Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 53, No. 6 232 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 53 Description of genera and species 256 Nevadia, new genus 256 weeksi, new species 257 Mcsonacis Walcott 261 niickwitzi (Schmidt) 262 torelli (Moberg) 264 vermontana -

12.007 Geobiology Spring 2009

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 12.007 Geobiology Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. Geobiology 2009 Lecture 10 The Antiquity of Life on Earth Homework #5 Topics (choose 1): Describe criteria for biogenicity in microscopic fossils. How do the oldest describes fossils compare? Use this to argue one side of the Brasier-Schopf debate OR What are stromatolites; where are they found and how are they formed? Articulate the two sides of the debate on antiquity and biogenicity. Up to 4 pages, including figures. Due 3/31/2009 Need to know • How C and S- isotopic data in rocks are informative about the advent and antiquity of biogeochemical cycles • Morphological remains and the antiquity of life; how do we weigh the evidence? • Indicators of changes in atmospheric pO2 • A general view of the course of oxygenation of the atm-ocean system Readings for this lecture Schopf J.W. et al., (2002) Laser Raman Imagery of Earth’s earliest fossils. Nature 416, 73. Brasier M.D. et al., (2002) Questioning the evidence for Earth’s oldest fossils. Nature 416, 76. Garcia-Ruiz J.M., Hyde S.T., Carnerup A. M. , Christy v, Van Kranendonk M. J. and Welham N. J. (2003) Self-Assembled Silica-Carbonate Structures and Detection of Ancient Microfossils Science 302, 1194-7. Hofmann, H.J., Grey, K., Hickman, A.H., and Thorpe, R. 1999. Origin of 3.45 Ga coniform stromatolites in Warrawoona Group, Western Australia. Geological Society of America, Bulletin, v. 111 (8), p. -

Curator 9-2 Cover.Qxd

Volume 9 Number 2 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP Registered Charity No. 296050 The Group is affiliated to the Geological Society of London. It was founded in 1974 to improve the status of geology in museums and similar institutions, and to improve the standard of geological curation in general by: - holding meetings to promote the exchange of information - providing information and advice on all matters relating to geology in museums - the surveillance of collections of geological specimens and information with a view to ensuring their well being - the maintenance of a code of practice for the curation and deployment of collections - the advancement of the documentation and conservation of geological sites - initiating and conducting surveys relating to the aims of the Group. 2009 COMMITTEE Chairman Helen Fothergill, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery: Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 8AJ, U.K. (tel: 01752 304774; fax: 01752 304775; e-mail: [email protected]) Secretary David Gelsthorpe, Manchester Museum, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, U.K. (tel: 0161 3061601; fax: 0161 2752676; e-mail: [email protected] Treasurer John Nudds, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, U.K. (tel: +44 161 275 7861; e-mail: [email protected]) Programme Secretary Steve McLean, The Hancock Museum, The University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE2 4PT, U.K. (tel: 0191 2226765; fax: 0191 2226753; e-mail: [email protected]) Editor of Matthew Parkes, Natural History Division, National Museum of Ireland, Merrion Street, The Geological Curator Dublin 2, Ireland (tel: 353 (0)87 1221967; e-mail: [email protected]) Editor of Coprolite Tom Sharpe, Department of Geology, National Museums and Galleries of Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP, Wales, U.K.