Desiring Berlin: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

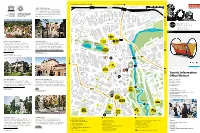

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

The Crisis Manager the Jacobsohn Era, 1914 –1938 INTRODUCTION

CHRONICLE 05 The crisis manager The Jacobsohn era, 1914 –1938 INTRODUCTION From the First World War to National Socialism A world in turmoil “Carpe diem” – seize the day. This Latin motto is carved over their positions. Beyond the factory gates, things on the gravestone of Dr. Willy Jacobsohn in Los Angeles were also far from peaceful: German society took a long and captures the essence of his life admirably. Given time to recover from the war. The period up until the the decades spanned by Jacobsohn’s career, this out- end of 1923 was scourged by unemployment, food and look on everyday life made a lot of sense: after all, housing shortages, and high inflation. The “Golden his career at Beiersdorf took place during what was Twenties” offered a brief respite, but even in the heyday arguably the most turbulent period in European history. of Germany’s first democracy, racist and anti-Semitic In fact, there are quite a few historians who describe feelings were simmering below the surface in society the period between 1914 and 1945 as the “second and politics, erupting in 1933 when the National Socia- Thirty Years War.” lists came to power. Jewish businessman Jacobsohn The First World War broke out shortly after Jacob- was no longer able to remain in Germany and, five years sohn joined the company in 1914. Although the war later, was even forced to leave Europe for America. ended four years later, Beiersdorf continued to suffer However, by then he had succeeded in stabilizing the crisis after crisis. Dr. Oscar Troplowitz and Dr. -

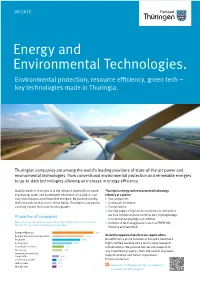

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

A Study of the Space That Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The lotP s of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College Recommended Citation Latimer, Carrie Grace, "The lotsP of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 430. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/430 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLOTS OF ALEXANDERPLATZ: A STUDY OF THE SPACE THAT SHAPED WEIMAR BERLIN by CARRIE GRACE LATIMER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MARC KATZ PROFESSOR DAVID ROSELLI APRIL 25 2014 Latimer 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Berlin Alexanderplatz: The Making of the Central Transit Hub 8 The Design Behind Alexanderplatz The Spaces of Alexanderplatz Chapter Two: Creative Space: Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz 23 All-Consuming Trauma Biberkopf’s Relationship with the Built Environment Döblin’s Literary Metropolis Chapter Three: Alexanderplatz Exposed: Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Film 39 Berlin from Biberkopf’s Perspective Exposing the Subterranean Trauma Conclusion 53 References 55 Latimer 3 Acknowledgements I wish to thank all the people who contributed to this project. Firstly, to Professor Marc Katz and Professor David Roselli, my thesis readers, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and thoughtful critiques. -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

German Culture 1910- Music

German Culture 1910- Music During the mid 1920s, cabaret was a popular entertainment within cities Berlin and Munich, as the lift of censorship and hedonism of a society which had “lost everything” was lived out within these cabaret shows. Pre- viously under an authoritarian government, both entertainment and social activities were tightly regulated, causing many citizens to love the relaxed social attitudes of Weimar. The first cabaret in Germany dated back to 1901, however in the rule of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German cabarets were strictly forbidden to perform and promote its bawdy humour, provocative dancing and political satire. After the Weimar governments lifting of cen- sorship, cabarets began to transform and flourish, with entertainment in berlin through cabarets and nightclubs dominated by sex and politics, (with stories, jokes, songs and dancing all laced with sexual innuendo, also following no political line, meaning any party or leader was open to criti- cism or mockery). Especially after decades of restrictive, authoritarian gov- ernment, Weimar was a period of social liberalisation. Post 1924 economic revival saw many people seeking new forms of leisure activities, one being cabaret. Cabaret led to people being more open about their sexuality and gender too. Photos show Josephine Baker, an American dancer naked on stage and a revue at the Apollo theatre in Berlin, with chorus girls only covering themselves partly by flowers. This is significant in Germany con- sidered the previous culture of the Kaiser, this was unheard of. However Weimar Germany and the culture of cabaret also led to social divisions be- tween families and of classes in Germany too. -

Curriculum Vitae Germany

Historisches Institut Dr. Alexander Schmidt Akademischer Rat Universität Jena · Einrichtung · 07737 Jena Fürstengraben 13 07743 Jena Curriculum Vitae Germany Telefon: +49 36 41 9-4979 Telefax: +49 36 41 9-310 02 E-Mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC DEGREES Jena, 29. Februar 2020 M.A. (1,0, 2001, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena), Dr.phil. (summa cum laude, 2005, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena) ACADEMIC POSITION Akademischer Rat, Historisches Institut, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena PREVIOUS POSITIONS 07/2009-03/2017 Juniorprofessor of Intellectual History, Research Centre “Laboratory Enlightenment”, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 10/2004-12/2008 Research fellow at the Collaborative Research Centre 482 “The Weimar-Jena phenomenon: Culture around 1800” (Sonderforschungsbereich 482 “Ereignis Weimar-Jena. Kultur um 1800”), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 7/2001–1/2002 Research fellow at the Department of History (Early Modern Studies), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena GRANTS, AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS 7/2018 (together with Professor Paul Cheney, University of Chicago) Summer Institute for University and College Teachers sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities ($ 110,694), Visiting Faculty at University of Chicago 12/2017 Initial grant by the Centre for the Study of the Global Condition (Leipzig) for the “Human rights without religion?” project (5500 €) 7/2015-11/2016 Feodor-Lynen-Fellowship for Experienced Researchers (offered by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation) at the John U. -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

Thuringia.Com

www.thats-thuringia.com That’s Thuringia. Ladies and Gentlemen, Thuringia is the region where successful collaboration between entrepreneurs and researchers goes back centuries. Looking to the future has been a long-standing tradition here. Just take Carl Zeiss, Ernst Abbe, and Otto Schott, who joined forces in Jena to lay the foundations for the modern optics industry and for a productive partnership between business and science. It’s a success story that the entrepreneurs and scientists in our Free State are continuing to write to this very day. And in the process, our producers and services providers can draw upon a multifaceted research environment which currently comprises no less than nine universities and universities of applied sciences, a total of 14 institutions run by the Fraunhofer, Leibniz, Max-Planck, and Helmholtz scientific societies, as well as eight research institutions with close ties to the economy. It’s the variety and the optimal mix of locational advantages that makes Thuringia so attractive for investors from all over the world. The central location of our Land at the heart of Germany will soon become even more of an advantage thanks to the new ICE high-speed train junction in Erfurt, which will significantly reduce travelling time to Berlin, Munich, and Frankfurt am Main. International companies seeking to locate to Thuringia can choose from our many top-notch industrial sites, which are situated along major highways and also include large-scale locations for those investors in need of more space. By now, Thuringia has surpassed Baden-Württem- berg as the Federal Land within Germany with the highest number of industrial operations per 100,000 inhabitants. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Hobbs, Mark (2010) Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2182/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930 Mark Hobbs BA (Hons), MA Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of History of Art Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the urban topography of Berlin’s working-class districts, as seen in the art, architecture and other images produced in the city between 1924 and 1930. During the 1920s, Berlin flourished as centre of modern culture. Yet this flourishing did not exist exclusively amongst the intellectual elites that occupied the city centre and affluent western suburbs. It also extended into the proletarian districts to the north and east of the city. Within these areas existed a complex urban landscape that was rich with cultural tradition and artistic expression. This thesis seeks to redress the bias towards the centre of Berlin and its recognised cultural currents, by exploring the art and architecture found in the city’s working-class districts. -

Soundscapes of the Urban Past

Sounds Familiar Intermediality and Remediation in the Written, Sonic and Audiovisual Narratives of Berlin Alexanderplatz Andreas Fickers, Jasper Aalbers, Annelies Jacobs and Karin Bijsterveld 1. Introduction When Franz Biberkopf, the protagonist of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz steps out of the prison in Tegel after four years of imprisonment, »the horrible moment« has arrived. Instead of being delighted about his reclaimed liberty, Biberkopf panics and feels frightened: »the pain commences«.1 He is not afraid of his newly gained freedom itself, however. What he suffers from is the sensation of being exposed to the hectic life and cacophonic noises of the city – his »urban paranoia«.2 The tension between the individual and the city, between the inner life of a character and his metropolitan environment is of course a well established topic in the epic litera- ture of the nineteenth century, often dramatized by the purposeful narrative confronta- tion between city life and its peasant or rural counterpoint.3 But as a new literary genre, the Großstadtroman, or big city novel, only emerges in the early twentieth century, and Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is often aligned with Andrei Bely’s Petersburg (1916), James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) or John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925) as an outstanding example of this new genre.4 What distinguishes these novels from earlier writings dealing with the metropolis is their experimentation with new forms of narra- tive composition, often referred to as a »cinematic style« of storytelling. At the same time, however, filmmakers such as David W. Griffiths and Sergei Eisenstein developed 1 Döblin 1961, 13.