Deciphering the Messages of Baltimore's Monuments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of War Memorial Design

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN war memorial may take many forms, though for most people the first thing that comes to mind is probably a freestanding monument, whether more sculptural (such as a human figure) or architectural (such as an arch or obelisk). AOther likely possibilities include buildings (functional—such as a community hall or even a hockey rink—or symbolic), institutions (such as a hospital or endowed nursing position), fountains or gardens. Today, in the 21st century West, we usually think of a war memorial as intended primarily to commemorate the sacrifice and memorialize the names of individuals who went to war (most often as combatants, but also as medical or other personnel), and particularly those who were injured or killed. We generally expect these memorials to include a list or lists of names, and the conflicts in which those remembered were involved—perhaps even individual battle sites. This is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however; the ancestors of this type of memorial were designed most often to celebrate a victory, and made no mention of individual sacrifice. Particularly recent is the notion that the names of the rank and file, and not just officers, should be set down for remembrance. A Brief History of War Memorial Design 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Ancient Precedents The war memorials familiar at first hand to Canadians are most likely those erected in the years after the end of the First World War. Their most well‐known distant ancestors came from ancient Rome, and many (though by no means all) 20th‐century monuments derive their basic forms from those of the ancient world. -

A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives

Governing Baltimore: A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives William G. LeFurgy, Susan Wertheimer David, and Richard J. Cox Baltimore City Archives and Records Management Office Department of Legislative Reference 1981 Table of Contents Preface i History of the Mayor and City Council 1 Scope and Content 3 Series Descriptions 5 Bibliography 18 Appendix: Mayors of Baltimore 19 Index 20 1 Preface Sweeping changes occurred in Baltimore society, commerce, and government during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From incorporation in 1796 the municipal government's evolution has been indicative of this process. From its inception the city government has been dominated by the mayor and city council. The records of these chief administrative units, spanning nearly the entire history of Baltimore, are among the most significant sources for this city's history. This guide is the product of a two year effort in arranging and describing the mayor and city council records funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. These records are the backbone of the historical records of the municipal government which now total over three thousand cubic feet and are available for researchers. The publication of this guide, and three others available on other records, is preliminary to a guide to the complete holdings of the Baltimore City Archives scheduled for publication in 1983. During the last two years many debts to individuals were accumulated. First and foremost is my gratitude to the staff of the NHPRC, most especially William Fraley and Larry Hackman, who made numerous suggestions regarding the original proposal and assisted with problems that appeared during the project. -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

Sports, Colonialism, and US Imperialism

SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM FORUM Sport, Colonialism, and United States Imperialism GERALD R. GEMS Department of Health and Physical Education North Central College BY 1914 EUROPEAN POWERS, LED BY GREAT BRITAIN, France, and Germany, con- trolled 85 percent of the earth’s land surface. By that time the United States, itself a former colony, had become a major player in the imperial process. Over the past century a num- ber of American historians have glorified such expansionism as a heroic struggle, a roman- tic adventure, a benevolent mission, and a Darwinian right or inevitability. In doing so, they constructed (some might say invented) national identities.1 Only more recently, since the 1960s, have scholars questioned imperialism and its practices. Post-colonial scholars, such as C.L.R. James, and revisionist historians have used a more critical lens, sometimes from the perspective of the conquered and colonized. James’s influential Beyond a Boundary (1964) assumed a Marxist paradigm in its investiga- tion of the role of cricket in the process of subjugation. Most other analyses have taken similar theoretical perspectives. Over the past dozen years, British historians, led by J.A. Mangan, have conducted a thorough examination of the role of sports and education in cultural imposition. American and European scholars, however, have not kept pace. Allen Guttmann’s Games and Empires (1994) remains the only comprehensive American study, while Joel Franks has published two recent inquiries into cross-cultural sporting experi- ences in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. Joseph Reaves’s Taking in a Game: A History of Baseball in Asia (2002) is a welcome addition to this short list. -

Loyola College in Maryland 2002–2003

LOYOLA COLLEGE IN MARYLAND 2002–2003 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOGUE STR ED O IV NG L T LL RUTHS WE College of Arts and Sciences The Joseph A. Sellinger, S.J. School of Business and Management 4501 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21210-2699 410-617-2000 http://www.loyola.edu Important The provisions of this publication are not to be Approved by: regarded as a contract between the student and Loyola College. The College reserves the right to State Department of Education of Maryland change courses, schedules, calendars, and any other Regents of the University of the State of New York provisions or requirements when such action will Approved for Veteran’s Education serve the interest of the College or its students. Member of: Students are responsible for acquainting themselves with the regulations pertinent to their status. The AACSB International – The Association to College reserves the right to modify its regulations in Advance Collegiate Schools of Business accordance with accepted academic standards and Adult Education Association of U.S.A. to require observance of the modifications. American Association for Higher Education Association of American Colleges Loyola College does not discriminate on the basis Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities of race, sex, color, national and ethnic origin, age, Council for Advancement and Support of Education religion, and disability in the administration of Independent College Fund of Maryland any of its educational programs and activities or Maryland Association for Higher Education with respect to admission and employment. The Maryland Independent College and University Designated Compliance Officer to ensure compli- Association ance with Title IX of the Education Amendment Middle States Association of Colleges and of 1972 is Toi Y. -

ADDENDUM a Case 1:03-Cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 2 of 30

Case 1:03-cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 1 of 30 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND BETSY CUNNINGHAM et al. : Plaintiffs : Civil Action No. JFM-03-1058 vs. : KIMBERLY AMPREY FLOWERS et al. : Defendants : CONSENT DECREE ADDENDUM A Case 1:03-cv-01058-JFM Document 269-2270-1 Filed 08/15/1308/19/13 Page 2 of 30 RULES AND REGULATIONS of the CITY OF BALTIMORE. DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS Affecting Management, Use, Government And Preservation With Respect To All Land, Property and Activities Under The Control Of THE DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS Whereas Article VII, Section 67(f) of the Baltimore City Charter, 1996 Edition, as amended, provides as follows: “The Director of Recreation and Parks shall have the following powers and duties: (f) To adopt and enforce rules and regulations for the management, use, government and preservation of order with respect to all land, property, and activities under the control of the Department. To carry out such regulations, fines may be imposed for breaches of the Rules and Regulations as provided by law." Now, therefore, the Director of the Department of Recreation and Parks on this ______day of _________________, 2013, does make, publish and declare the following Rules and Regulations for the government and preservation of order within all areas over which the regulatory powers of the Director extend. The new rules and regulations shall be effective as of this date. All former rules and regulations previously issued, declared or printed are hereby amended and superseded. -

Montage Fiches Rando

Leaflet Walks and hiking trails Haute-Somme and Poppy Country 8 Around the Thiepval Memorial (Autour du Mémorial de Thiepval) Peaceful today, this Time: 4 hours 30 corner of Picardy has become an essential Distance: 13.5 km stage in the Circuit of Route: challenging Remembrance. Leaving from: Car park of the Franco-British Interpretation Centre in Thiepval Thiepval, 41 km north- east of Amiens, 8 km north of Albert Abbeville Thiepval Albert Péronne Amiens n i z a Ham B . C Montdidier © 1 From the car park, head for the Bois d’Authuille. The carnage of 1st July 1916 church. At the crossroads, carry After the campsite, take the Over 58 000 victims in just straight on along the D151. path on your right and continue one day: such is the terrible Church of Saint-Martin with its as far as the village. Turn left toll of the confrontation war memorial built into its right- toward the D151. between the British 4th t Army and the German hand pillar. One of the many 3 Walk up the street opposite s 1st Army, fewer in number military pilgrimages to Poppy (Rue d’Ovillers) and keep going e r but deeply entrenched. Country, the emblematic flower as far as the crossroads. e Their machine guns mowed of the “Tommies”. By going left, you can cut t down the waves of infantrymen n At the cemetery, follow the lane back to Thiepval. i as they mounted attacks. to the left, ignoring adjacent Take the lane going right, go f Despite the disaster suffered paths, as far as the hamlet of through the Bois de la Haie and O by the British, the battle Saint-Pierre-Divion. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Welcome

TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome ................................................................................................ 3 Schedule of Events ...............................................................................4 Lyft Transportation Pick Up Points................................................... 4 Places to Stay ........................................................................................ 5 Places to Eat ..........................................................................................6 Downtown Parking Map .....................................................................8 Runner Safety Flag System .................................................................9 RaceSafe ................................................................................................. 10 98Rock .05K ..........................................................................................11 Expo Parking, Hours and Shuttle ......................................................12-13 Bib Number Email Details ..................................................................15 Race Shirt Exchange & Policy ............................................................16 Public Transportation........................................................................... 17 Prohibited Items ...................................................................................18 Runner’s Bag Check .............................................................................19 Pace Groups ..........................................................................................21 -

Building a Better Howard Street

BUILDing a Better Howard Street Lead Applicant: Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Transit Administration (MDOT MTA) In partnership with: Baltimore City Department of Transportation (BCDOT) Downtown Partnership of Baltimore (DPOB) Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC) Holly Arnold Director, Office of Planning and Programming MDOT MTA 6 St. Paul Street, Suite 914 Baltimore, MD 21202 [email protected] 410.767.3027 FY 2018 BUILD Discretionary Grant Program Total Project Costs: $71.3 Million BUILD 2018 Funds Requested: $25.0 Million Project Overview . 1 1 Project Description . 2 1.1 Corridor Overview . 2 Howard Street Howard BUILDing a Better 1.2 BUILDing a Better Howard Street . 4 1.3 Project Need . 7 1.4 Introduction to Project Benefits . 10 2 Project Location . 11 2.1 Project Location . 11 3 Grant Funds & Sources/Uses of Project Funds . 13 3.1 Capital Sources of Funds . 13 3.2 Capital Uses of Funds . 13 3.3 Operations and Maintenance Cost Uses of Funds . 14 4 Selection Criteria . 15 4.1 Merit Criteria . 15 State of Good Repair . 15 Safety . 16 Economic Competitiveness . 18 Environmental Protection . 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Quality of Life . 21 Innovation . 22 Street Howard BUILDing a Better Partnership . 24 Non-Federal Revenue for Transportation Infrastructure Investment 25 4.2 Project Readiness . 26 Technical Feasibility . 26 Project Schedule . 26 Required Approvals . 28 Assessment of Risks and Mitigation Strategies . 28 5 Project Costs and Benefits . 28 5.1 Major Quantitative Benefits . 28 OF CONTENTS TABLE 5.2 Major Qualitative Benefits . 29 5.3 Summary Results . 30 Appendix I Benefit Cost Analysis Appendix II Letters of Support Appendix III BUILD Information Form The historical photo of Howard Street used as a backdrop throughout this application is by Robert Mottar / Baltimore Sun INTRODUCTION Howard Street was once downtown Baltimore’s premier shopping district, but in the 1970s it went into decline. -

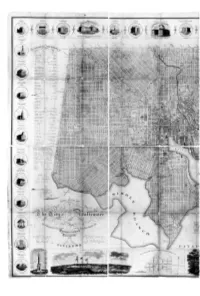

184 Maryland Historical Magazine Thomas Poppleton’S Map: Vignettes of a City’S Self Image

184 Maryland Historical Magazine Thomas Poppleton’s Map: Vignettes of a City’s Self Image Jeremy Kargon ritten histories of Baltimore often refer to thePlan of the City of Baltimore, published originally in 1823. Typically but imprecisely credited to Thomas WPoppleton, this map illustrated the city plan he produced between 1816 and 1822. City politicians had commissioned a survey just before the War of 1812, but Poppleton began his work in earnest only after the conflict ended. Once adopted, the work determined the direction of Baltimore’s growth until well after the Civil War.1 Although this street layout significantly influenced the city’s nineteenth-cen- tury development, a second feature of this document has also attracted historians of the city’s architecture. The map’s publisher’s arranged thirty-five small engravings around the border of the map illustrating public buildings in use or under construc- tion at the time of the original publication. They gave each illustration a simple title and provided additional descriptive information about the building, including the architect’s name, the building’s date of completion, and the building’s cost. These pictures are a useful record of Baltimore’s earliest significant architecture, particu- larly for those buildings demolished before the age of photography. Historians’ treatments of these images, and of the map itself, have typically looked at these illustrations individually.2 Consideration of their ensemble, on the other hand, provides evidence for discussion of two broader themes, the public’s perception of architecture as a profession and as a source of shared material cul- ture, and the development of that same public’s civic identity as embodied in those buildings. -

City of Baltimore Phone Numbers

Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management City of Bernard C. “Jack” Young, Mayor BALTIMORE David McMillan, Director Maryland City of Baltimore Phone Numbers Residents can contact these phone numbers to access various City services (note: this is not an exhaustive list). Thank you for your patience during this IT outage. Baltimore City Council Office of the Council President 410-396-4804 District 1 410-396-4821 District 2 410-396-4808 District 3 410-396-4812 District 4 410-396-4830 District 5 410-396-4819 District 6 410-396-4832 District 7 410-396-4810 District 8 410-396-4818 District 9 410-396-4815 District 10 410-396-4822 District 11 410-396-4816 District 12 410-396-4811 District 13 410-396-4829 District 14 410-396-4814 Baltimore City Fire Department (BCFD) Headquarters 410-396-5680 Community Education & Special Events 410-396-8062 Office of the Fire Marshall 410-396-5752 Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD) Animal Control 311 B'More for Healthy Babies 410-396-9994 BARCS 410-396-4695 Community Asthma Program 410-396-3848 Crisis Information Referral Line 410-433-5175 Dental Clinic / Oral Health Services 410-396-4501 Druid Health Clinic 410-396-0185 Emergency Preparedness & Response 443-984-2622 Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management City of Bernard C. “Jack” Young, Mayor BALTIMORE David McMillan, Director Maryland Environmental Health 410-396-4424 Guardianship 410-545-7702 Health Services Request 443-984-3996 Immunization Program 410-396-4544 Lead Poisoning Prevention Program 443-984-2460 LTC Ombudsman 410-396-3144 Main Office 410-396-4398 -

Triumph Plant Announced Recovered State to Have

The Midland Journal VOL. LXVI RISING SUN, CECIL COUNTY, MD., FRIDAY, MAY NO. 47 CIVILIAN DEFENSE Be Sure To Weather DINNER MEETING State To Have Merger Of OF LIONS CLUB RESCINDED Buy And Balloon • 15,000 Extra Plant Wea^ dinner meeting the Triumph The Executive Committee of the At ithe of It is Thursday ev- Maryland of Defense met on ing Sun Lions Club, on Council Mify 17, the Nominating Com- Farm May 16th and rescinded the civilian A Poppy Recovered ening, Workers reported following slate Announced defense protective regulations pre- mittee the the election to be held .) tune 7: viously promulgated by the Council May to Poppy Days, Hubert Miller, who operates 4he for 19 30 are President, F. M. Kennard; Ist vice- .5,000 Prisoners Of War and issued a policy statemen'i con- when the little red flower, a symbol Hugh Evans farm, weßt of Rising Be Taken Over By president, Charles Croiheis; 2nd vice To fining its future status and opera- , of honor to dead warriors, Sun, on Saturday picked up in the America’s president, Wm. C. Graham; 3rd vice Hons. The regulations rescinded by , be worn. woodis on the premises, a red silk will president, William McNumee; secre- To Aid Farmers die Executive Committee were: The members of 'the American Le- parachute attached to a fiber case Noma tary, Charlton Poist; treasurer, Ev- The Electric Air Raid protection regulations ( gion dedicating their efforts to about six Inches square, containing are erett F. Johnson; tail-twister, Claude governing blackoun procedure within ( the distribution and sale of the pop- various weather recording Instru- And Buick; lion tamer.