Vanderbilt University Undergraduate Catalog Calendar 2014/2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnolia News Issue, May 2021

MAGNOLIA NEWS MAY, 2021 * VOLUME 23, ISSUE 9 www.vanderbilt.edu/vwc The Vanderbilt Woman’s Club brings together the women of Vanderbilt University; provides an opportunity for intellectual, cultural and social activities within the community and the University; supports and assists the mission of the University; and Members of the Board sponsors the Vanderbilt Woman’s Club Stapleton/Weaver Endowed Scholarship through fundraising. 2020-2021 Tracy Stadnick President’s Letter President Ahh Spring! How “mud-luscious” and “puddle-wonderful” as E.E. Cummings Joy Allington-Baum stated in one of my favorite poems “in Just-”. What are your favorite Past President poems? What words resonate with you? Join us to hear Kate Daniels, Vanderbilt’s professor of poetry, present the “Curious Power of Poetry” Sharon Hels on May 10th. Vice President/Programs We are hosting our first “Meet and Three” Food Drive for Second Harvest Elisabeth Sandberg Food Bank on May 15th. You will “meet” VWC friends and donate “Meat and Treasurer Three” food. Bring your food donation to Kelly Chamber’s house with a drive- thru food drop off. We encourage you to collect donations from your neighbors to bring along. Thank you for helping. Ebbie Redwine Recording Secretary Lunch Bunch, Book Clubs, Music group, Antiques, MahJongg, Cribbage, Garden Club and Chocolate Lovers are meeting on zoom or in person while Sara Plummer following VU COVID guidelines. Read the newsletter to see dates and times. Corresponding Secretary Read Joy Allington-Baum’s article, “From the Archives,” and discover our Kelly Chambers fascinating history and its connection with Magnolia trees on campus. -

CHALENE HELMUTH Senior Lecturer Department of Spanish And

CHALENE HELMUTH Senior Lecturer Department of Spanish and Portuguese Faculty Head of Sutherland House The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons Peabody #560 230 Appleton Place Vanderbilt University [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Spanish American Literature, University of Kentucky, 1991 M.A., Spanish, University of Kentucky, 1988 B.A., Spanish, Asbury College, 1986 Elementary and Secondary Education, San José, Costa Rica TEACHING Vanderbilt University Senior Lecturer (Fall 2003-present) SPAN 1001 iSeminar: Strategies for Successful Study Abroad iSeminar: Eco-Conscious Travel SPAN 1100 Spanish for True Beginners SPAN 1101/1102 Elementary Spanish I and II SPAN 1101G Spanish for Reading SPAN 1103 Intensive Elementary Spanish SPAN 1103 Eco-critical Perspectives in Latin American Literature SPAN 3301W Intermediate Spanish Writing SPAN 3202 Spanish for Oral Communication SPAN 3303 Introduction to Hispanic Literature SPAN 3340 Advanced Spanish Conversation SPAN 4425 Spanish American Literature from 1900 to the Present SPAN 4740 Spanish-American Literature of the Boom Era SPAN 4948 Senior Honors Thesis Faculty Director, Vanderbilt Initiative in Scholarship and Global Engagement (VISAGE) Costa Rica, 2008-2013 INDS 3831 Seminar in Global Citizenship, Service, and Research: Ecotourism, Civic Engagement, and Corporate Social Responsibility Faculty Director, Vanderbilt/Tulane in Costa Rica, 2014-2016 SPAN 3893 Reading Green: Engaging the Environment in Spanish American Literature Helmuth 2 Middlebury College Undergraduate Faculty, Spanish Language -

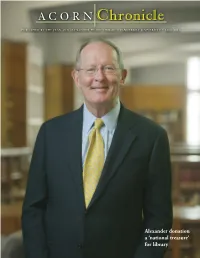

ACORN Chronicle

ACORN Chronicle PUBLISHED BY THE JEAN AND ALEXANDER HEARD LIBRARY • VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY • F ALL 2011 Alexander donation a ‘national treasure’ for library Special Collections welcomes Sen. Alexander’s donation of papers V A N D ne of Vanderbilt’s most well- E R B I L T known graduates, U.S. Sen. U N I V E Lamar Alexander (BA’62) and R S I T Y O S his wife, Honey Alexander, have made one P E C I A L of the most important donations in the C O L L Jean and Alexander Heard Library’s histo - E C T I O N ry by giving their pre-Senate papers to S Special Collections. The collection contains a wealth of his - torical documents from Alexander’s political campaigns, his two terms as governor, Honey Alexander’s roles as wife, mother, first lady and advocate for family causes, along with the senator’s correspondence with close friend and author Alex Haley. Papers from Alexander’s tenure as president of the University of Tennessee and U.S. sec - retary of education are also included. “Honey and I felt that the archives (above) Nissan CEO Marvin Runyon and Lamar Alexander shake hands as the first Sentra rolls should reflect the voices of the countless off the production line in March 1985. Alexander was instrumental in drawing both Japanese Tennesseans who have worked with us to manufacturing and the auto industry to Tennessee. (top of page) As Tennessee’s governor, Lamar raise educational standards, attract indus - Alexander addresses the crowd at his inauguration in January 1983. -

Vanderbilt University the History of Vanderbilt

Vanderbilt University: The History of Vanderbilt University http://www.vanderbilt.edu/history.html Vanderbilt University: The History of Vanderbilt University Search People Finder | Help | Site Index The History of Vanderbilt University Related links: About Vanderbilt | Chancellor's homepage | Bios of past Chancellors Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt was in his 79th year when he decided to make the gift that founded Vanderbilt University in the spring of 1873. The $1 million that he gave to endow and build the university was the Commodore's only major philanthropy. Methodist Bishop Holland N. McTyeire of Nashville, a cousin of the Commodore's young second wife, went to New York for medical treatment early in 1873 and spent time recovering in the Vanderbilt mansion. He won the Commodore's admiration and support for the project of building a university in the South that would "contribute to strengthening the ties which should exist between all sections of our common country." McTyeire chose the site for the campus, supervised the construction of buildings and personally planted many of the trees that today make Vanderbilt a National Arboretum. At the outset, the university consisted of one Main Building 3 of 6 9/18/08 2:11 PM Vanderbilt University: The History of Vanderbilt University http://www.vanderbilt.edu/history.html (now Kirkland Hall), an astronomical observatory and houses for professors. Landon C. Garland was Vanderbilt's first chancellor, serving from 1875 to 1893. He advised McTyeire in selecting the faculty, arranged the curriculum and set the policies of the university. For the first 40 years of its existence, Vanderbilt was under the auspices of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. -

From Piano Girl to Professional: the Changing

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2014 FROM PIANO GIRL TO PROFESSIONAL: THE CHANGING FORM OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION AT THE NASHVILLE FEMALE ACADEMY, WARD’S SEMINARY FOR YOUNG LADIES, AND THE WARD- BELMONT SCHOOL, 1816-1920 Erica J. Rumbley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rumbley, Erica J., "FROM PIANO GIRL TO PROFESSIONAL: THE CHANGING FORM OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION AT THE NASHVILLE FEMALE ACADEMY, WARD’S SEMINARY FOR YOUNG LADIES, AND THE WARD-BELMONT SCHOOL, 1816-1920" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 24. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/24 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The University

THE UNIVERSITY Vanderbilt, founded 130 years ago by a $1 million gift by Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, is one of the nation’s leading institutions of higher learning, a mid-size, private comprehensive research university that emphasizes undergraduate learning and living experiences. Since its inception, the university has taken great pride in the quality of education – and the quality of life – its students enjoy. Each of the four undergraduate colleges – College of Arts and Science, School of Engineering, Blair School TBALL of Music and Peabody College – attracts students with varying goals and dreams. Whichever school they enroll in, students receive a valuable and versatile education and are an integral part of the University’s community of scholars. Members of the undergraduate student body, including Vanderbilt student-athletes, are outstanding academic achievers and active participants in Vanderbilt’s 350-plus extracurricu- FOO lar organizations. The University attracts students from many ethnic, cultural, socio-economic, geographic and religious facilities. Off campus, undergraduates have all the urban conveniences backgrounds, and all are encouraged to listen to and learn from one offered by one of America’s foremost cities, Nashville. The city, located on another. The incoming freshman class of 2004 features the greatest the scenic Cumberland River, possesses a rare blend of big-city amenities diversity in Vanderbilt history. and small-town charm. Its collection of cultural activities, attractions, restaurants, parks and sporting -

The Magazine of Vanderbilt University's College of Arts

artsandS CIENCE The magazine of Vanderbilt University’s College of Arts and Science F A L L 2 0 0 9 spring2008 artsANDSCIENCE 1 whereAER YOU? tableOFCONTENTS FALL 2009 20 12 6 30 6 Opportunity Vanderbilt departments Two of Vanderbilt’s volunteer leaders discuss the expanded financial aid initiative. A View from Kirkland Hall 2 Arts and Science Notebook 3 8 2 1 Arts and Science in the World A Middle Eastern Calling Five Minutes With… 10 Leor Halevi exercises his imagination and love of history in the study of Islam. Up Close 14 Great Minds 16 0 2 Passion Wins Out Rigor and Relevance 18 Open Book 25 Studying what they love is the path to career success for Arts and Science alumni. And the Award Goes To 26 Forum 30 8 2 The NBA’s International Playmaker First Person 32 Basketball’s global growth and marketing opportunities thrive under alumna Giving 34 Heidi Ueberroth’s leadership. College Cabinet 36 In Place 44 NEIL BRAKE Parting Shot 46 artsANDC S IENCE© is published by the College of Arts and Science at Vanderbilt University in cooperation with the Office of Development and Alumni Relations Communications. You may contact the editor by e-mail at [email protected] or by U.S. mail at PMB 407703, 2301 Vanderbilt Place, Nashville, TN 37240-7703. Editorial offices are located in the Loews Vanderbilt Office Complex, 2100 West End Ave., Suite 820, Nashville, TN 37203. Nancy Wise, EDITOR Donna Pritchett, ART DIRECTOR Jenni Ohnstad, DESIGNER Neil Brake, Daniel Dubois, Steve Green, Jenny Mandeville, John Russell, PHOTOGRAPHY Lacy Tite, WEB EDITION Nelson Bryan, BA’73, Mardy Fones, Tim Ghianni, Miron Klimkowski, Craig S. -

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: the Story Behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: The Story behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America Linda Jones Hall* Abstract — When Clyde Pharr published his massive English translation of the Theodosian Code with Princeton University Press in 1952, two former graduate students at Vanderbilt Uni- versity were acknowledged as co-editors: Theresa Sherrer David- son as Associate Editor and Mary Brown Pharr, Clyde Pharr’s wife, as Assistant Editor. Many other students were involved. This article lays out the role of those students, predominantly women, whose homework assignments, theses, and dissertations provided working drafts for the final volume. Pharr relied heavily * Professor of History, Late Antiquity, St. Mary’s College of Mary- land, St. Mary’s City, Maryland, USA. Acknowledgements follow. Portions of the following items are reproduced by permission and further reproduction is prohibited without the permission of the respective rights holders. The 1949 memorandum and diary of Donald Davidson: © Mary Bell Kirkpatrick. The letters of Chancellor Kirkland to W. L. Fleming and Clyde Pharr; the letter of Chancellor Branscomb to Mrs. Donald Davidson: © Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt University. The following items are used by permission. The letters of Clyde Pharr to Dean W. L. Fleming and Chancellor Kirkland; the letter of A. B. Benedict to Chancellor O. C. Carmichael: property of Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander -

University of Minnesota News Service • April 1, 1953

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA NEWS SERVICE • APRIL 1, 1953 p'f e", 'S Ye I e A 50 ~J ':. FRENCH MOVIE FlF.ST ON SPRING SCHEDULE AT i Uf (FOR D-lMEDIATE RELEASE) liLa Ronde", a French film, will open the University of Minnesota Film society' s spring program \-lith a three-da.y run April 15-17. Showings in Northrop Memorial auditorium are scheduled at 3:30 and S p.m. April 15 with additional performances at 8 p.m. April 16 and 17. Based on the Arthur Schnitzler play, ''Reigen'', the movie takes its name from Oscar Straus 1 liLa Ronde" waltz. It presents a string of romantic episodes which take place in Vienna at the turn of the century. Anton Walb:"ook, Simone Simon, Danie11e Darrieux, Jean-Louis Barrau1t and Gerard Philipe are among tu'1e stars. "La Ronde ll was named "best picture of the year" by the British Film Academy and won the grand prize at 1951 film festivals in Venice, Cannes, Brussels and Cuba. Other films on the spring calendar are "The Man in the White Suit" (British) April 22; "Open City" (Italian) April 29; liThe River" (British) May 6; "Under the Paris Sk'J" (French) May 13; and "Fantasia" (American) May 22. With the exception of "Fantasia" -- which will be shown at 4 and 7:30 p.m. on a Friday -- all these movies will be presented at 3 :30 and 8 p.m. Wednesdays in Northrop audito:'iUI:1. Admission is 74 cents for adults, 35 cents for juniors. In addition, the societ.7 has planned a program of film classics -- a group of Charlie Chaplin comedies for April 9, IIGrapes of Wrath" April 24 and "Midsummer Night's Dream" with Olivia de HaViland, James Cagney, Joe E. -

The Vanderbilt University Colony of the International Fraternity of Delta

The Vanderbilt University Colony of The International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi Table of Contents I. Petitioning Letter II. Letters of Recommendation A. Dr. Andy Van Schaack, Colony Advisor, Vanderbilt University B. Rupinder Saggi, Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Economics Department C. Kimberly Loudon, District Director, Vanderbilt University D. Vanessa Leithoff, District Director, Vanderbilt University E. Madison Whitehouse, Mid-South Regional Vice President III. Vanderbilt University A. History B. Campus Photos C. Facts/Statistics IV. Departments A. Economics Department B. Human and Organizational Development C. Public Policy D. Owen Graduate School of Management 1. Business Minor V. The Vanderbilt Colony of Delta Sigma Pi A. Purpose B. History and Activities C. Calendar of Events 1. 2017 Fall Semester 2. 2018 Spring Semester D. Member Statistics E. Photos VI. Members of the Vanderbilt Colony Letters of Recommendation A. Kimberly Loudon, Vanderbilt Colony District Director B. Vanessa Leithoff, Vanderbilt Colony District Director C. Dr. Andy Van Schaack, Vanderbilt Colony Faculty Advisor D. Rupinder Saggi, Director of Undergraduate Studies, Economics Department E. Madison Whitehouse, Mid-South Regional Vice President Vanderbilt University History 1873: Cornelius Vanderbilt donates $1 million to endow and build the university in the spring; Holland McTyeire chooses site for campus; offers work in the liberal arts and sciences and embraced several profesional schools in addition to its college 1892-1901: Women at Vanderbilt -

2017 Vanderbilt Football Media Guide

ANCHOR 2 @VANDYFOOTBALL DOWN VANDERBILT FOOTBALL 2016 3 SCHEDULE/FACTS/CONTENTS TEAM INFORMATION 2017 VANDERBILT SCHEDULE Date Opponent Kickoff Location Venue COACHES/STAFF Sept. 2 @ Middle Tennessee 7 pm CT Murfreesboro, Tenn. Floyd Stadium Derek Mason .....Head Coach/Defensive Coordinator Sept. 9 Alabama A&M TBA Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium C.J. Ah You ...................................................................DL Warren Belin ..........................................................OLBs Sept. 16 Kansas State 6:30 pm CT Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium Jeff Genyk .............Special Teams Coordinator/RBs Sept. 23 Alabama * TBA Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium Gerry Gdowski ..........................................................QBs Sept. 30 @ Florida * TBA Gainesville, Fla. Ben Hill Griffin Stadium Cortez Hankton ........................................................WRs Oct. 7 Georgia * TBA Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium Andy Ludwig ....................Offensive Coordinator/TEs Oct. 14 @ Ole Miss * TBA Oxford, Miss. Vaught-Hemingway Stadium Chris Marve ............................................................. ILBs Marc Mattioli ............................................................DBs Oct. 28 @ South Carolina * TBA Columbia, S.C. Williams-Brice Stadium Cameron Norcross .....................................................OL Nov. 4 Western Kentucky TBA Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium James Dobson ........................ Head Strength Coach Nov. 11 Kentucky * TBA Nashville Vanderbilt Stadium Tyler Clarke ...........................Asst. -

TEMPLATE-Spencer Stuart Documentation-Master-032816

www.spencerstuart.com Position and Candidate Specification Chancellor PREPARED BY: Jennifer Bol Michele E. Haertel Shailaja Panjwani September 2019 Assignment: 62611-006 1 VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY About the University Vanderbilt University Founded in 1873, Vanderbilt is a globally renowned research university located on a parklike campus set in the urban heart of Nashville, Tennessee. The students, faculty, staff and alumni comprising the university’s remarkably collegial and cooperative community share a commitment to the university’s mission of creating and deploying the ideas, knowledge and leaders that foster positive change in the world. Vanderbilt University offers an immersive living–learning experience for its approximately 6,800 undergraduate students, with programs in the liberal arts and sciences, engineering, music, education and human development. Vanderbilt also is home to nationally and internationally recognized graduate schools of law, education, business, medicine, nursing and divinity, and offers robust graduate-degree programs across a range of disciplines, with a collective graduate enrollment of approximately 6,000. Its 10 colleges and schools are closely linked by a university-wide commitment to interdisciplinary teaching and research. Top-ranked in both academics and financial aid, Vanderbilt is dedicated to inclusive excellence, drawing the world’s brightest students, faculty and distinguished visitors from all cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. The university’s prominent alumni base includes Nobel Prize winners, members of Congress, governors, ambassadors, judges, admirals, CEOs, university presidents, physicians, attorneys, journalists, social activists, and professional sports figures. The trajectory of Vanderbilt’s dynamic hometown, Nashville, has mirrored and is supported by the university’s own trajectory. The university works in close and constant partnership with city, state and federal leaders to support quality of life in our region and to leverage shared priorities and opportunities.