The Realignment of Khartoum's Foreign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India-Sudan Relations Political Relations India-Sudan Relations Go

India-Sudan Relations Political relations India-Sudan relations go back in history to the time of the Nilotic and Indus Valley Civilizations. There is evidence of contacts and possibly trade almost 5,000 years ago through Mesopotamia. In 1935, Mahatma Gandhi stopped over in Port Sudan (on his way to England by boat) and was welcomed by the Indian community there. In 1938, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter also stopped over in Port Sudan on their way to Britain and were hosted to a function at the home of Chhotalal Samji Virani. The Graduates General Congress of Sudan formed in 1938 drew heavily from the experience of the Indian national Congress. British Indian troops fought alongside Sudanese in Eritrea in 1941 winning the decisive battle of Keren (earning the Bengal Sappers a Victoria Cross for mine clearance in Metemma, now on the Sudan-Ethiopia border). The first Sudanese Parliamentary elections in 1953 were conducted by Shri Sukumar Sen, India’s Chief Election Commissioner (the Sudanese Election Commission, formed in 1957, drew heavily on Indian election literature and laws). A Sudanization Committee established in February 1954 to replace British officials finished its work in April 1955 with budgetary support from India for compensation payments. India opened a diplomatic representation in Khartoum in March 1955. In April 1955, the interim Prime Minister of the Sudan, Ismail Al Azhari and several Ministers transited through New Delhi on their way to Bandung for the first Afro- Asian Relations Conference. At the 1955 Bandung Conference, the delegation from a still not independent Sudan did not have a flag to mark its place. -

Abdel Halim Mohammed Abdel Halim Distinguished Physician Before and After Sudan’S Independence

OBITUARIES For the full versions of articles in this section see bmj.com Abdel Halim Mohammed Abdel Halim Distinguished physician before and after Sudan’s independence Abdel Halim Mohammed Abdel Halim ary groups Hashmab and the Dawn. He was Halim was a brilliant medical diagnostician was born in colonial Sudan and became a regular contributor to Dawn magazine and in the days when investigative procedures the first Sudanese doctor to occupy senior coauthor of a book, entitled Death of a Life. His were rudimentary, and he was an inspirational medical roles at home and abroad. He was groups together with others gave rise to the teacher. His medical ward rounds were a stage a senior physician before and after Sudan Sudan graduates’ congress, of which Halim for rigorous medical teaching, poetry, high gained independence from Great Britain, was a founding member. From the congress flown prose, Sudanese proverbs, and verses and he was the first Sudanese doctor to sprang the main political parties, which led from the Koran. It was all delivered in per- become a member of the movement towards fect English and perfect classical Arabic with the Royal College of Sudanese independ- panache and humour. Physicians, in London, ence. As the first The top of his class, Halim qualified in 1948, and 14 years president of the Sudan from Kitchener School of Medicine, Khar- later its first Sudanese Medical Association, toum, in 1933. Soon after his internship he fellow. He maintained Halim took a leading was appointed a medical tutor. He trained his friendship with his part in drafting the medical students, house officers, and medi- British teachers and col- political memorandum cal registrars from then until well after his leagues long after their that sought autonomy retirement from the ministry of health. -

Köppen Signatures” of Fossil Plant Assemblages for Effective Heat Transport of Gulf Stream to Subarctic North Atlantic During Miocene Cooling

Biogeosciences, 10, 7927–7942, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7927/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7927-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evidence from “Köppen signatures” of fossil plant assemblages for effective heat transport of Gulf Stream to subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene cooling T. Denk1, G. W. Grimm1, F. Grímsson2, and R. Zetter2 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Correspondence to: T. Denk ([email protected]) Received: 8 July 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 August 2013 Revised: 29 October 2013 – Accepted: 2 November 2013 – Published: 6 December 2013 Abstract. Shallowing of the Panama Sill and the closure 1 Introduction of the Central American Seaway initiated the modern Loop Current–Gulf Stream circulation pattern during the Miocene, The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) at 17–15 but no direct evidence has yet been provided for effec- million years (Myr) was the last phase of markedly warm cli- tive heat transport to the northern North Atlantic during mate in the Cenozoic (Zachos et al., 2001). The MMCO was that time. Climatic signals from 11 precisely dated plant- followed by the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) bearing sedimentary rock formations in Iceland, spanning at 14.2–13.8 Myr correlated with the growth of the East 15–0.8 million years (Myr), resolve the impacts of the devel- Antarctic Ice Sheet (Shevenell et al., 2004). In the Northern oping Miocene global thermohaline circulation on terrestrial Hemisphere this cooling is reflected by continuous sea ice in vegetation in the subarctic North Atlantic region. -

The Influence of South Sudan's Independence on the Nile Basin's Water Politics

A New Stalemate: Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 The Influence of South Sudan’s Master thesis in Sustainable Development Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Jon Roozenbeek Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 15 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2014. E, 15 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 196 Master thesis in Sustainable Development A New Stalemate: The Influence of South Sudan’s Independence on the Nile Basin’s Water Politics Jon Roozenbeek Supervisor: Ashok Swain Evaluator: Eva Friman Master thesis in Sustainable Development Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Research Aim .................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Methods ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. Case Selection ................................................................................................................. 7 1.5. Limitations ..................................................................................................................... -

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021)

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 10 Abidjan DV 8 Abidjan F1 5 Abidjan F2B 1 Abidjan F4 8 Abidjan FX 33 Abidjan IR1 10 Abidjan IR2 18 Abidjan IR5 14 Abu Dhabi CR1 39 Abu Dhabi DV 29 Abu Dhabi E1 1 Abu Dhabi E3 81 Abu Dhabi F1 14 Abu Dhabi F2B 7 Abu Dhabi F3 12 Abu Dhabi F4 60 Abu Dhabi FX 16 Abu Dhabi I5 3 Abu Dhabi IR1 89 Abu Dhabi IR2 17 Abu Dhabi IR5 84 Abu Dhabi SB1 9 Abu Dhabi SE 4 Accra CR1 1 Accra E3 15 Accra F1 15 Accra F2B 4 Accra F3 22 Accra F4 13 Accra FX 23 Accra IR1 35 Accra IR2 48 Accra IR5 41 Accra SB1 9 Accra SE 32 Addis Ababa CR1 17 Addis Ababa DV 9 Addis Ababa E1 1 Addis Ababa F1 12 Addis Ababa F2B 13 Addis Ababa F3 5 Page 1 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa FX 125 Addis Ababa IR1 90 Addis Ababa IR2 83 Addis Ababa IR5 47 Addis Ababa SB1 4 Addis Ababa SE 57 AIT Taipei DV 2 AIT Taipei E1 6 AIT Taipei E2 18 AIT Taipei E3 5 AIT Taipei EW 1 AIT Taipei F1 15 AIT Taipei F2B 1 AIT Taipei F3 12 AIT Taipei F4 92 AIT Taipei FX 36 AIT Taipei I5 33 AIT Taipei IR1 11 AIT Taipei IR2 6 AIT Taipei IR3 7 AIT Taipei IR5 30 AIT Taipei SB1 30 Algiers CR1 26 Algiers DV 45 Algiers F4 2 Algiers FX 23 Algiers IR1 42 Algiers IR2 9 Algiers IR5 30 Algiers SE 5 Almaty CR1 1 Almaty DV 134 Almaty E3 4 Almaty F1 1 Almaty F2B 1 Almaty FX 49 Almaty IB1 1 Almaty IR1 4 Almaty IR2 6 Almaty IR5 58 Amman CR1 8 Amman CR2 1 Page 2 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Amman DV 57 Amman E2 6 Amman -

The Sudanese Civil War - the Effect of Arabisation and Islamisation

Research and Science Today No. 2(12)/2016 International Relations THE SUDANESE CIVIL WAR - THE EFFECT OF ARABISATION AND ISLAMISATION Paul DUTA1 Roxelana UNGUREANU2 ABSTRACT: SUDAN IS NOT AN ARAB ETHNIC EVEN IF THE ARAB CIVILIZATION IS FUNDAMENTAL IN THIS STATE, SUDANESE BEING CONSIDERED AFRICANS OF DIFFERENT ETHNIC ORIGINS. THE PROCESS OF ISLAMISATION OF EGYPT HAS IGNORED SUDAN, BEING RECORDED ONLY OCCASIONAL RAIDS IN THE SUDAN OVER MORE THAN THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM WHAT HAS ATTRACTED THE EMBLEM OF THE BORDER OF ISLAM (TURABI USES THE WORDS “FRONTIER ZONE ARABS”). THE TRANSFORMATION OF SUDAN IN A SPACE OF ARAB CIVILIZATION HAS NOT BEEN CARRIED OUT BY MILITARY CONQUEST BUT BY TRADE AND ARAB MISSIONARIES WHICH BANISH CHRISTIAN INFLUENCES, ARABISATION ESTABLISHED ITSELF THOUGH ISLAM (TWO THIRDS OF THE POPULATIONS) AND RABA LANGUAGE (HALF OF THE POPULATION). THE PROSPECTS OF IRRECONCILABLE ISLAMIC ON THE STATE THE SUDANESE OF TABANI AND KUTJOK REFLECTS THE GRAVITY OF THE CONTRADICTIONS WHICH IT CONTAINS THE FOUNDATIONS OF THIS STATE. THE POPULATION IN THE SOUTH OF THE COUNTRY COULD ACCEPT A FEDERALIZATION, BUT THE LEADERSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC POLICY IN THE NORTH WOULD NOT BE ACCEPTED LOSS OF POWER; THE POLITICAL ELITE IN THE SOUTH OF THE COUNTRY STILL PRESSED FOR THE SECESSION. FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE STATE UNITY, THE CIVIL WAR BETWEEN THE ELITE OF THE NORTH AND THE MINORITY POPULATIONS OF SOUTH AFRICA (NILE MINORITY DINKA, NUER MINORITY OF BAHR AL-GHAZAL, MINORITIES IN THE AREA OF THE UPPER NILE AND THE EQUATOR) IS POWERED BY THE UNFAIRNESS OF THE REDISTRIBUTION AND MONOPOLISE RESOURCES AFTER OBTAINING INDEPENDENCE. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

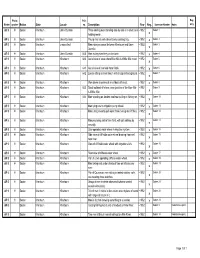

State Locale Description Year Neg. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three Smiling Men Standing Side by Side in Market, One Hold

Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three smiling men standing side by side in market, one ~1952 Sudan 1 x holding melon. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Young man at work decoratively painting tray. ~1952 x Sudan 2 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum unspecified Man riding on camel between Khartoum and Umm ~1952 Sudan 3 x Durmān. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān 645 Men exiting river ferry on to shore. ~1952 x Sudan 4 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 640 Aerial view of area where Blue Nile & White Nile meet. ~1952 Sudan 5 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 641 Aerial view of riverside farm fields. ~1952 x Sudan 6 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 642 Locals sitting on river beach with bridge in background. ~1952 Sudan 7 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum View down shoreline of small boat off coast. ~1952 x Sudan 8 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 643 Small sailboat off shore, near junction of the Blue Nile ~1952 Sudan 9 x & White Nile. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 644 Man standing on docked row boat pulling in fishing net. ~1952 Sudan 10 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man tying cow to irrigation pump wheel. ~1952 x Sudan 11 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man using levee to pull water from river up to cliff face. ~1952 Sudan 12 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man preparing soil in farm field, with girl walking by ~1952 Sudan 13 x casually. -

The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East

water Article The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link between the Köppen Climate Classifications and the δ18O and δ2H Values of Precipitation Mojtaba Heydarizad 1, Luis Gimeno 1,*, Rogert Sorí 1,2 , Foad Minaei 3,4 and Javad Eskandari Mayvan 5 1 Centro de Investigación Mariña, Environmental Physics Laboratory (EPhysLab), Campus As Lagoas s/n, Universidade de Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Instituto Dom Luiz (IDL), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 3 Department of Geography, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 917794883, Iran; [email protected] 4 Geographic Information Science/System and Remote Sensing Laboratory (GISSRS. Lab), Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 9177794883, Iran 5 Regional Water Company of Khorasan Razavi, Mashhad 9185916196, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Middle East is faced with a water shortage crisis due to its semiarid and arid climate. In this paper, precipitation as an important part of the water cycle was evaluated in 43 stations across the Middle East using the stable isotope technique to study the parameters which influence the stable isotope content of precipitation. First, the stepwise regression model was applied to determine the Citation: Heydarizad, M.; main geographical and climatological factors affecting the stable isotopes in precipitation. Secondly, Gimeno, L.; Sorí, R.; Minaei, F.; the stepwise model was also used to simulate the stable isotope values in precipitation. Furthermore, Mayvan, J.E. The Stable Isotope due to the notable climatic variations across the Middle East, the precipitation sampling stations Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link were classified into six groups based on the Köppen climate zones. -

Sudan, Country Information

Sudan, Country Information SUDAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES V HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS ANNEX A - CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B - LIST OF MAIN POLITICAL PARTIES ANNEX C - GLOSSARY ANNEX D - THE POPULAR DEFENCE FORCES ACT 1989 ANNEX E - THE NATIONAL SERVICE ACT 1992 ANNEX F - LIST OF THE MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF SUDAN ANNEX G - REFERENCES TO SOURCE DOCUMENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum/human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for accuracy, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up-to-date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

Egypt Vs. Algeria – the Nasty Politics of Football

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona opiniónCIDOB EGYPT VS. ALGERIA – THE NASTY 52 POLITICS OF FOOTBALL DECEMBER 2009 Francis Ghilès Senior Researcher, CIDOB n Thursday 12th November the bus ferrying the Algerian national football team from Cairo airport to the hotel was stoned by Egyptians – the police did not intervene before a number of players were seriously wounded, Osome even needed stitches. The Pharaohs won 2-0 against the Fennecs (desert fox) thus forcing a play- off which was to be played in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, on 18th November. The outcome of that match would decide which team would qualify to represent Africa for the finals of the World Cup due in South Africa next year. Ugly incidents occurred between supporters of both teams after the first match which spread to three countries in the run up to the second match. Reckless reporting fanned by Egyptian and Algerian political leaders resulted in large scale demonstrations in Algiers when the Algerian popular newspaper Chourouk reported one Algerian fan had died – it later turned out he had fainted. President Mubarak’s sons joined the fray: on Egyptian television they attacked Algerians for being terrorists. Blogs meanwhile went into overdrive, Algerian bloggers promising to avenge the blood of their brother “killed” in Cairo, Egyp- tians sneering at Algerians for having been colonised by the French for 132 years. The Algerian authorities meanwhile slapped a $600m tax bill on Orascom, the Egyptian company which has a high profile in Algeria and whose headquarters were thrashed by crowds of Algerian supporters. -

No. ICC-02/05-02/09 24 September 2009 1 Original

ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 1/33 EO PT Original: English No .: ICC-02/05-02/09 Date: 24 September 2009 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Sylvia Steiner, Presiding Judge Judge Sanji Mmasenono Monageng Judge Cuno Tarfusser SITUATION IN DARFUR, THE SUDAN IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR V. BAHAR IDRISS ABU GARDA Public Redacted Version of Prosecution’s “DOCUMENT CONTAINING THE CHARGES SUBMITTED PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 61(3) OF THE STATUTE” filed on 10 September 2009 Source: Office of the Prosecutor No. ICC-02/05-02/09 1 24 September 2009 ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 2/33 EO PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Karim A. A. Khan Legal Representatives of Victims Legal Representatives of Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants for Participation/Reparation The Office of Public Counsel for Victims The Office of Public Counsel for the Defence States Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Ms Silvana Arbia Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC-02/05-02/09 2 24 September 2009 ICC-02/05-02/09-91-Red 25-09-2009 3/33 EO PT I. THE PERSON CHARGED................................................................................................................ 5 II. STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................................................................................................... 6 A. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................