This Is an Accepted Manuscript of an Article Published in Organization on 18 Th March 2018, Available Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reverend Paul John Flowers

Curriculum Vitae The Reverend Paul John Flowers Educated at Barton Peveril Grammar School, Hampshire, Bristol University (BA in Theology) and Geneva University (Certificate in Ecumenical Studies and Ecumenical Scholarship from the World Council of Churches). A Fellow of both the Royal Society of Arts and the Royal Geographical Society, in 2012 he was additionally elected to a Fellowship of the Chartered Institute of Bankers in Scotland (FCIBS). Co-operatives Paul was the Chair of the Board of the Co-operative Banking Group and also the Chair of the Co-operative Bank plc, between 2010 and June 2013. He was appointed as a Director of the Banking Group in the summer of 2009. He was additionally the senior Deputy Chair of the Co- operative Group as a whole which runs all the family of businesses in the UK. He was the Chair of the Group’s Remuneration and Appointments Committee and of the Diversity Strategy Group. He was a member of the Group Board between 2008 and 2013 and was previously a Director of the United Co-operative Society Ltd until its merger with the Group. He was an elected member of the Executive of the European Association of Co-operative Banks, of the Board of the International Association of Co-operative Banks, and a member of the All Nations Board of the International Co-operative and Mutual Insurance Federation. He was also the Chair of the International Co-operative Alliance’s Global Development Fund, and instrumental in raising many millions of dollars for the Fund’s work. Within the co-operative family Paul chaired the Yorkshire Co-operative Employees Pension Fund and was a trustee of the PACE pension scheme, one of the largest pension schemes in the country. -

Kelly Review Analysis

Failings in management and governance Report of the independent review into the events leading to the Co-operative Bank's capital shortfall Sir Christopher Kelly 30 April 2014 Failings in management and governance Report of the independent review into the events leading to the Co-operative Bank's capital shortfall Sir Christopher Kelly 30 April 2014 TERMS OF REFERENCE To investigate the robustness and timeliness of the Board's and the management's strategic decisions which ultimately led to the need to adopt a Capital Action Plan by the Co-operative Bank to address its £1.5 billion capital shortfall; To look at the management structure and culture in which those decisions were taken; lines of accountability which governed those decisions; and the processes which led to them; To identify lessons which can be learnt to strengthen the Co-operative Bank and the wider Co-operative Group, and the co-operative business model generally; To review the financial accounting practices of the Bank, the representations made by management to the independent auditors regarding these practices and the role of the independent auditors in reporting to the Audit Committee of the Bank and giving an opinion on its financial statements; To publish the findings of its review to members, colleagues and other key stakeholders. LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Report has been prepared by Sir Christopher Kelly as independent reviewer commissioned by the executive teams, together with the Boards, of the Co-operative Group Limited (the Group) and the Co- operative Bank plc (the Bank). It is published at their request. The Review's Terms of Reference are set out above. -

Project Verde

House of Commons Treasury Committee Project Verde Sixth Report of Session 2014–15 Volume II Oral evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 October 2014 HC 728–II [Incorporating HC 300, Session 2013-14] Published on 23 October 2014 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £21.50 Treasury Committee The Treasury Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of H M Treasury, HM Revenue and Customs and associated public bodies. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) and further details can be found on the Committee’s web pages at www.parliament.uk/treascom. Current membership Mr Andrew Tyrie MP (Conservative, Chichester) (Chairman) Steve Baker MP (Conservative, Wycombe) Mark Garnier MP (Conservative, Wyre Forest) Stewart Hosie MP (Scottish National Party, Dundee East) Mr Andy Love MP (Labour, Edmonton) John Mann MP (Labour, Bassetlaw) Mr Pat McFadden MP (Labour, Wolverhampton South West) Mr George Mudie MP (Labour, Leeds East) Jesse Norman MP (Conservative, Hereford and South Herefordshire) Teresa Pearce MP (Labour, Erith and T hamesmead) David Ruffley MP (Conservative, Bury St Edmunds) Alok Sharma MP (Conservative, Reading West) John Thurso MP (Liberal Democrat, Caithness, Sutherland, and Easter Ross) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Local Election Results 2008

Local Election Results May 2008 Andrew Teale August 15, 2016 2 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2008 Typeset by LATEX Compilation and design © Andrew Teale, 2012. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. This file, together with its LATEX source code, is available for download from http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/leap/ Please advise the author of any corrections which need to be made by email: [email protected] Contents Introduction and Abbreviations9 I Greater London Authority 11 1 Mayor of London 12 2 Greater London Assembly Constituency Results 13 3 Greater London Assembly List Results 16 II Metropolitan Boroughs 19 4 Greater Manchester 20 4.1 Bolton.................................. 20 4.2 Bury.................................... 21 4.3 Manchester............................... 23 4.4 Oldham................................. 25 4.5 Rochdale................................ 27 4.6 Salford................................. 28 4.7 Stockport................................ 29 4.8 Tameside................................. 31 4.9 Trafford................................. 32 4.10 Wigan.................................. 34 5 Merseyside 36 5.1 Knowsley................................ 36 5.2 Liverpool................................ 37 5.3 Sefton.................................. 39 5.4 St Helens................................. 41 5.5 Wirral.................................. 43 6 South Yorkshire 45 6.1 Barnsley................................ 45 6.2 Doncaster............................... 47 6.3 Rotherham............................... 48 6.4 Sheffield................................ 50 3 4 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2008 7 Tyne and Wear 53 7.1 Gateshead............................... 53 7.2 Newcastle upon Tyne........................ -

Corporate Governance Case Studies Financial Services Edition

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIES FINANCIAL SERVICES EDITION Mak Yuen Teen and Richard Tan CPAAOM3499_297x210_Corporate Governance Report Covers_FA.indd 2 22/5/20 8:41 am CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIES Financial Services Edition Mak Yuen Teen and Richard Tan Editors First published July 2020 Copyright ©2020 Mak Yuen Teen and CPA Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except for inclusion of brief quotations in a review. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, CPA Australia Ltd. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIES: FINANCIAL SERVICES EDITION Authors : Mak Yuen Teen, PhD, FCPA (Aust.) Email: [email protected] Richard Tan MBA, FCA (S’pore) Email: [email protected] Published by : CPA Australia Ltd 1 Raffles Place #31-01 One Raffles Place Singapore 048616 Website : cpaaustralia.com.au Email : [email protected] ISBN : 978-981-14-6595-6 CONTENTS PREFACE ABOUT THE EDITORS BOARD RESPONSIBILITIES AND PRACTICES GOLDMAN SACHS: HELLO LLOYD, MEET BLANKFEIN 1 HSBC: WHO’S THE BOSS? 6 THE CO-OPERATIVE BANK: THE WITHERING FLOWERS 10 FINDING THE WHISTLE AT BARCLAYS 14 MISCONDUCT COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA: ROGUE ONE 20 WELLS FARGO: FORGONE REPUTATION? 26 COMMINSURE: NO ONE’S COVERED 33 UNAUTHORISED TRADING ANOTHER DAY, -

Financial Statements 2009 Contents

The Co-operative Bank plc Support and security in the community. Financial statements 2009 Contents Chair’s statement 2 Chief executive’s overview 4 Business and financial review 6 Sustainable development 12 The Board 14 Report of the Board of directors 16 Corporate governance report 21 Remuneration report 27 Independent auditors’ report 35 Consolidated income statement 36 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 37 Consolidated balance sheet 38 Bank balance sheet 39 Consolidated statement of cash flows 40 Bank statement of cash flows 41 Consolidated and Bank statements of changes in equity 42 Basis of preparation and accounting policies 43 Risk management 53 Capital management 89 Critical judgments and estimates 90 Notes to the financial statements 93 Responsibility statement 135 Notice of Annual General Meeting 136 1 Chair’s statement The Co-operative Financial Services (CFS) was formed in 2002 from the bringing together of The Co-operative Bank and The Co-operative Insurance Society. This year, upon the merger with Britannia Building Society, the business has further developed its profile as the UK’s most diversified mutual financial services provider. But behind this process of evolution lies the strength that comes from being a key part of The Co-operative Group, the UK’s largest consumer co-operative. Our position in The Co-operative Group opens up to our customers, and particularly our growing body of members, the opportunity to benefit from a unique range of services including food stores, pharmacy, funeral directors, travel and of course financial services. We benefit too from a long and distinguished history, a firm grounding in our community and a great reputation amongst people who do business with us. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 573 15 January 2014 No. 104 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 15 January 2014 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 833 15 JANUARY 2014 834 to 2% yesterday. We will continue to give people support, House of Commons in particular with our triple lock on pensions that delivered the biggest ever single cash increase in the Wednesday 15 January 2014 state pension, and we will continue to deal with the deficit. The real threat to the cost of living would be a Labour Government, who would put up taxes and see The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock interest rates increased. PRAYERS 12. [901930] Neil Carmichael (Stroud) (Con): Does the Secretary of State agree that the real way to deal with [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] cost of living issues is to pursue economic growth with a long-term strategy to rebalance the economy, and that that applies to Northern Ireland, particularly in Oral Answers to Questions engineering and manufacturing? Mrs Villiers: My hon. Friend is absolutely right. The only way to achieve a sustainable increase in living NORTHERN IRELAND standards is to run the economy efficiently and effectively, and to have a credible plan to deal with the deficit. That The Secretary of State was asked— is the way we can keep interest rates low and deal with inflation, and that is the way we can make this country a Cost of Living wealthier place. -

Mangan, A., & Byrne, A. (2018)

Mangan, A. , & Byrne, A. (2018). Marginalising co-operation? A discursive analysis of media reporting on the Co-operative Bank. Organization, 25(6), 794-811 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418763276 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1177/1350508418763276 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Sage at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1350508418763276 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Organization on 18 th March 2018, available online: https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418763276 Anita Mangan Keele University, UK Aidan Byrne University of Wolverhampton, UK Marginalising co-operation? A discursive analysis of media reporting on the Co- operative Bank Abstract Recently there has been renewed academic interest in co-operatives. In contrast, media accounts of co-operatives are relatively scarce, particularly in the UK, where business reporting usually focuses on capitalist narratives, with alternatives routinely marginalised until a scandal pushes them into the public eye. This paper analyses media coverage of the UK’s Co-operative Bank (2011-15), tracing its transformation from an unremarkable presence on the UK high street to preferred bidder for Lloyds Bank branches, and its subsequent near collapse. -

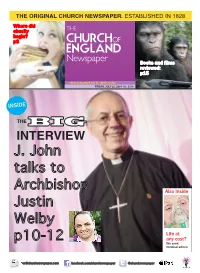

J. John Talks to Archbishop Justin Welby P10-12

THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER. ESTABLISHED IN 1828 Where did obesity THE begin? CHURCHOF p8 ENGLAND Newspaper Books and films reviewed: p15 NOW AVAILABLE ON NEWSSTAND FRIDAY, JULY 25, 2014 No: 6238 INSIDE THE BIG INTERVIEW J. John talks to Archbishop Also Inside Justin Welby Life at p10-12 any cost? We seek medical advice [email protected] facebook.com/churchnewspaper @churchnewspaper THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER. ESTABLISHED IN 1828 Where did obesity THE begin? CHURCHOF p8 ENGLAND Newspaper Books and films reviewed: p15 NOW AVAILABLE ON NEWSSTAND INSIDE FRIDAY, JULY 25, 2014 No: 6238 J. John talks THE BIG to Archbishop Justin Welby INTERVIEW p10-12 Reactions to the Bill Opposition to the assisted dying bill remains strong, Assisted dying is despite the House of Lord’s vote to send the measure to Committee Stage. The debate was inconclusive last Friday, with the speeches largely balanced between those in favour and those opposed to changing the current law. Stoic, Archbishop says Christian Concern said it was unsurprising that Lord Falconer’s bill is being given more time for scrutiny. Andrea Minichiello Williams, Chief Executive of The Archbishop of York has led would spare them trouble. But in the campaign group, urged the Lords to remember Church of England opposition to fact the best service one could do this is a matter of life and death. assisted dying in an impassioned for them would be to accept their She said: “It cannot be decided on the basis of debate in the House of Lords. care and to show appreciation of sound-bites nor simply on the basis of sentiment, Almost 130 speakers took parT in them at the end of one’s life.” however much we all wish to see an end to suffering. -

Download the Chapters 13 Run the Party’S Unofficial Blog Politics for People (See

annual report 2007 the co-operative party This annual report has been produced by The Co-operative Party. For information or more details, please contact: The Co-operative Party 77 Weston Street London SE1 3SD t: 020 7367 4150 f: 020 7407 4476 e: [email protected] w: www.party.coop This document is available on our website. To receive an electronic version, please contact Dorota Kseba at [email protected], or telephone 020 7367 4155. The Co-operative Party Annual Report 2007 Chair’s report 1 Organisation 2 A review of the highlights of the year 4 - 5 Celebrating the Party’s 90th Anniversary 6 National Politics 7 - 10 Policy 11 - 12 Party organisation & grass roots 13 - 14 Financial accounts 15 - 19 Co-operative Party Fund 20 - 30 CHAIR’S REPORT 2007 has been, for the Co-operative Party, the busiest in recent memory. In celebrating our 90th birthday, we have shown the full breadth of the co-operative impact on Government policy making. From enterprise to public services to consumer rights and lo- cal democracy, the co-operative sector contributes strongly to the Government’s agenda. We have commemorated our distinguished history and demonstrated our bright present and future. The Party’s job has always been to promote co-operative policies and interests in the most effective and credible manner possible. We do this with the support, both financial and moral, of the UK co-operative sector – something that we are both grateful for and rightly proud. As a result of our work, the contribution that co-operatives and mutuals make to our economy and society is now better understood than ever before. -

Co-Operation Halted?

Matthews.qxp 04/08/2014 13:54 Page 74 74 The forward 2012 was a great year for the Co-operative Movement. The United Nations had march of designated it as the International Year of the Co-operation Co-operatives. Dame Pauline Green, President of the International Co-operative halted? Alliance, addressed the United Nations and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon told the world that, Nick Matthews ‘Co-operatives are a reminder to the international community that it is possible to pursue both economic viability and social responsibility.’ Co-ops UK and the Co-op Group rose to the occasion with a major conference and exhibition in Manchester called ‘Co-ops United’ (apologies to City fans!) Even David Cameron was swept along by ‘Big Society’ rhetoric and agreed to support one of the objectives of the Year, governments’ consolidation of Co-op legislation, through a new Co-operatives and Community Benefits Societies Act. Corporate capitalism was on the ropes; the co- Nick Matthews is a lifetime operative and mutual sector had weathered socialist and co-operator the banking crisis and was growing. who chairs Co-operatives Entering 2013, Co-ops had never had a UK, which brings together more favourable press; in the public’s eyes, organisations as diverse as we were a ‘good thing’. the Co-op Group, Suma Then the sky fell in; 9 May 2013 was the Wholefoods and the day of reckoning, when the ratings agency Woodcraft Folk. He Moody’s downgraded the Co-operative examines the problems that Bank’s debt rating to ‘junk’ status. -

For Peer Review

Organization Marginalising co-operation? A discursive analysis of media reporting on the Co-operative Bank Journal: Organization Manuscript ForID ORG-17-0077.R2 Peer Review Manuscript Type: Article alternative organisations, banking, Co-operative Bank, co-operatives, Keywords: discourse, framing, journalism, media, financial crisis Recently there has been renewed academic interest in co-operatives. In contrast, media accounts of co-operatives are relatively scarce, particularly in the UK, where business reporting usually focuses on capitalist narratives, with alternatives routinely marginalised until a scandal pushes them into the public eye. This paper analyses media coverage of the UK’s Co-operative Bank (2011-15), tracing its transformation from an unremarkable presence on the UK high street to preferred bidder for Lloyds Bank branches, and its subsequent near collapse. The paper charts changes in reporting and media interest in the bank through five discursive frames: member and customer service; standard financial reporting; Abstract: human interest, personality-driven journalism; the PR machine; and political coverage. Our analysis discusses three points: the politicisation of the story through covert and overt political values; simplification and sensationalism; and media hegemony. We argue that although moments of crisis provide an opening for re-evaluating the dominant reporting model, established frames tend to reassert themselves as a story develops. This produces good copy that reflects the interests of the publishers, but does not extend understanding of co-operative organisations. Thus the paper identifies the role of the media in delegitimising organisations with alternative governance structures, thereby promoting ideological and economic conformity. http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/organization Page 1 of 50 Organization 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Marginalising co-operation? A discursive analysis of media reporting on the Co- 9 10 11 operative Bank 12 13 14 15 16 Abstract 17 18 Recently there has been renewed academic interest in co-operatives.