Angela Carter's Postmodern Feminism and the Gothic Uncanny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quest for Female Empowerment in Angela Carter's Wise Children

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN Supervisor: Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of Professor Marysa Demoor the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Aline Lapeire 2009-2010 Lapeire ii Lapeire iii “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN The cover of Wise Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) Lapeire iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the help of the following people. I would hereby like to thank… … Professor MARYSA DEMOOR for supporting my choice of topic and sharing her knowledge about gender studies. Her guidance and encouragement have been very important to me. … DEBORA VAN DURME and Professor SINEAD MCDERMOTT for their interesting class discussions of Nights at the Circus and Wise Children. Without their keen eye for good fiction, I might have never even heard of Angela Carter and her beautiful oeuvre. … Several very patient librarians at the University of Ghent. … A great deal of friends who at times mocked the idea of a „gender dissertation‟, yet always showed their support when it was due. I especially want to thank my loyal thesis buddies MAX DEDULLE and MARTIJN DENTANT. The countless hours we spent together while hopelessly staring at a world behind the computer screen eventually did pay off. Moreover, eternal gratitude and a vodka-Red Bull go out to JEROEN MEULEMAN who entirely voluntarily offered to read and correct my thesis. -

The Consumption of Angela Carter

The Consumption of Angela Carter: Women, Toody and Power EMMA PARKER A great writer and a great critic, V. S. Pritchett, used to sav that he swallowed Dickens whole, at the risk of indigestion. I swallow Angela Carter whole, and then I rush to buy Alka Seltzer. The "minimalist" nouvelle cuisine alone cannot satisfy my appetite for fiction. I need a "maximalist" writer who tries to tell us many things, with grandiose happenings to amuse me, extreme emotions to stir my feelings, glorious obscenities to scandalise me, brilliant and malicious expressions to astonish me. (Almansi 217) L Vs GUIDO ALMANSI suggests, consuming Angela Carter's fic• tion is simultaneously satisfying and unsettling. This is partly because, as Hermione Lee has commented, Carter "was always in revolt against the 'tyranny of good taste'" (316). As a cham• pion of moral pornography, a cultural dissident who dared to disparage Shakespeare, and a culinary iconoclast who criticised the highly-esteemed cookery writer Elizabeth David, Carter out• raged many people. Yet this impiety also gives her work its ap• peal.1 Like the critical essays, her fiction is deliciously "improper" in that it interrogates and rejects what Hélène Cixous calls the realm of the proper, a masculine economy based on the principles of authority, domination and owner• ship — a realm in which, disempowered and dispossessed, women are without property ("Castration" 42, 50). Her fiction has an unsettling effect precisely because Carter seeks to "up• set" the patriarchal order, in part through her representation of consumption, which, by revealing and refiguring the relation• ship between women, food, and power, challenges the struc• tures that underpin patriarchy. -

Identity I N Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children

Performing (and) Identity In Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children Janine Root @ B .A. B. Ed A cnesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Lakehead University, Thnder Bay, Ontario, 1999 National Library BibliotMy nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Cana a Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wauinglm Strwt 385. rue WdlingWn WONK1AW o(I.waON K1AW Cwudr CMed. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Libmy of Cana& to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. Abstract In her last two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, Angela Carter examines some of the complex factors involved in the construction of identity, both within the fictional world, and for readers in their interaction with 'Le .jn-74 ,., I ,,,, 2f the fictix. 35 zhese f3ctxs, qezier is cf primary importance. -

Course Unit Descriptor

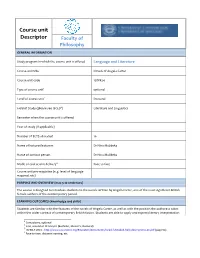

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

Feminism and Sexuality in Angela Carter's Shadow Dance And

International Journal of Research p-ISSN: 2348-6848 e-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 04 Issue 01 January2017 Contextualizing Bluebeard Patriarchy through Grotesque: Feminism and Sexuality in Angela Carter’s Shadow Dance and Heroes and Villains Ms. Richa Arora Ph.D Scholar, Lovely Professional University Phagwara SUPERVISED BY Dr J.P. Aggarwal ABSTRACT The purpose of this research paper is to bring awareness to the students of post-colonial fiction of Angela Carter. She won Nobel Prize for literature for her revolutionary feminism and deconstruction of patriarchy. Carter gives the image of the wolf to characterize the monstrous quality of his Bluebeards in her novels. The wolf is a deadly; in each plot of her novels there is a deadly conflict between wolf and the dove. Carter uses all the elements of the Gothic novels of Mrs. Anne Redcliff to create an atmosphere of horror and supernaturalism. The forces of darkness are in tune with the threatening atmosphere of the novel symbolizing death and destruction. Carter has used this tool in her short stories The Bloody Chamber as well. Carter uses the images of mirror, snow, blood, moon, fire, forest and old castles to depict the presence of her Bluebeards symbolic of bloodthirsty traditional patriarchy. In this study the main issues of sexuality of women, gender discrimination are investigated in detail. KEY WORDS: Traumatic, Holocaust, Community, Barbaric, Trilogy, Strategy The themes of power, gender, and „female Gothic‟” (Munford 61). Gamble sexuality dominate the novels of Angela Carter; contends that “Her heroines cover the whole she belongs to the Second Wave of feminism and range from objectified victims to oppressors of wanted to launch a crusade against male others” (Gamble 68). -

Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives

Postmodern Openings ISSN: 2068 – 0236 (print), ISSN: 2069 – 9387 (electronic) Coverd in: Index Copernicus, Ideas. RePeC, EconPapers, Socionet, Ulrich Pro Quest, Cabbel, SSRN, Appreciative Inquery Commons, Journalseek, Scipio EBSCO Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU Postmodern Openings, 2010, Year 1, VOL.3, September, pp: 93-138 The online version of this article can be found at: http://postmodernopenings.com Published by: Lumen Publishing House On behalf of: Lumen Research Center in Social and Humanistic Sciences BOTESCU–SIRETEANU, I.,(2010) Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives, Postmodern Openings, Year 1, Vol 3, September, 2010, pp: 93-138 Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU8 Abstract In a world where meaning has been deconstructed and reconstructed, where centers have lost their hegemony and notions such as truth, knowledge or history have been rendered relative by the ongoing ontological enquiry of the postmodern ideology, it is baffling to remark that not only in literature, but also in other fields that make use of discourses, there has been a return to and a reconsideration of the narrative. Nowadays, one can easily observe the narrative drive that enlivens various discourses, from the medical one to the one used in the academe or in official governmental documents. Brian McHale has even referred to the „narrative turn” in literary theory which, according to him, seems to answer to the loss of the metaphysical (McHale 4). Keywords: narrative turn, feminism, narrative dynamics, 8 Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU – “Transilvania” University from Brasov, Romania, Email Address: [email protected]. -

Playing the Female Fool: Metamorphoses of the Fool from Fireworks to the Bloody Chamber

Playing the Female Fool: Metamorphoses of the Fool from Fireworks to The Bloody Chamber by Cristina Di Maio ABSTRACT: This article looks at the representation of the fool in the first two short story collections by Angela Carter, namely Fireworks (1974) and The Bloody Chamber (1979). Its central argument is that the quintessentially subversive presence of the fool is theorized and developed in Carter’s earlier short stories, in a way that leads to a radical shift in her poetics and in the reader’s perception of her writing. In fact, a path of evolution of this figure is traced in Carter’s female characters in her first two short story collections, outlining how the female fool develops from an individualist and vengeful rebel in Fireworks to a more socially constructive dissident in The Bloody Chamber. The female fool is seen as an experimental symbol of female subversion which is deeply intertwined with Carter’s self-awareness as a feminist writer, developing alongside her first conceptualization of this figure. The article starts with an outline of the three fool figures which exemplify the female fool’s evolution from the first to the second short story collection; it then proceeds to analyze the short stories that foreground female fool figures. The last section focuses on the figure of the healing female fool, whose transformative potential eventually brings about long-lasting and constructive effects. KEY WORDS: fool; Angela Carter; grotesque; The Bloody Chamber; healing Fuori verbale/Entre mamparas/Hors de propos/Off the Record N. 24 – 11/2020 ISSN 2035-7680 346 I am all for putting new wine in old bottles, especially if the pressure of the new wine makes the old bottles explode. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The choice of literary fiction to the general exclusion of popular fiction is partly because the latter’s response to the Cold War has received some study, but also because study of the topic tends to overemphasise its source material. For example, see LynnDiane Beene paraphrased in Brian Diemert, ‘The Anti- American: Graham Greene and the Cold War in the 1950s’, in Andrew Hammond, ed., Cold War Literature: Writing the Global Conflict (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 213; and David Seed, American Science Fiction and the Cold War: Literature and Film (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), p. 192. 2. Caute, Politics and the Novel during the Cold War (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2010), p. 76. 3. Richard J. Aldrich, ‘Introduction: Intelligence, Strategy and the Cold War’, in Aldrich, ed., British Intelligence, Strategy and the Cold War, 1945–51 (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), p. 1. For useful summaries of the different schools of Cold War historiography, see S.J. Ball, The Cold War: An International History, 1947– 1991 (London and New York: Arnold, 1998), pp. 1–4; and Ann Lane, ‘Introduction: The Cold War as History’, in Klaus Larres and Lane, eds, The Cold War: The Essential Readings (Oxford and Malden: Blackwell, 2001), pp. 3–16. 4. Dwight D. Eisenhower quoted in John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, new edn (2005; London: Penguin, 2007), p. 123. In the mid-1940s, the US assertion that ‘in this global war there is literally no question, political or military, in which the United States is not interested’ was soon echoed by Vyacheslav Molotov’s claim that ‘[o]ne cannot decide now any serious problems of international relations without the USSR’ (quoted in Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000, new edn (1987; New York: Vintage Books, 1989), p. -

Subverting Children's Literature: a Feminist Approach to Reading Angela Carter

ARTÍCULOS UTOPÍA Y PRAXIS LATINOAMERICANA. AÑO: 25, n° EXTRA 6, 2020, pp. 501-510 REVISTA INTERNACIONAL DE FILOSOFÍA Y TEORÍA SOCIAL CESA-FCES-UNIVERSIDAD DEL ZULIA. MARACAIBO-VENEZUELA ISSN 1316-5216 / ISSN-e: 2477-9555 Subverting Children’s Literature: A feminist Approach to Reading Angela Carter Subvertir la literatura infantil: Un enfoque feminista para leer Angela Carter S.S NEIMNEH https://orcid.org/0000-0000-0000-0000 [email protected] Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan N.A AL-ZOUBI https://orcid.org/0000-0000-0000-0000 [email protected] Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan R.K AL-KHALILI https://orcid.org/0000-0000-0000-0000 [email protected] Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan Este trabajo está depositado en Zenodo: DOI: http://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.3987669 RESUMEN ABSTRACT Este artículo argumenta la importancia de los cuentos de This article argues the importance of the short stories of Angela Angela Carter en el campo de la literatura infantil y sus Carter to the field of children’s literature and its current adaptaciones actuales. Mira dos de sus historias. El resultado adaptations. It looks at two of her stories. The result is fiction es que la ficción se basa en algunos patrones de literatura building on some patterns of children’s literature yet with a infantil, pero con un matiz feminista que cuestiona los feminist tinge that questions the foundations of patriarchy. Her fundamentos del patriarcado. Sus historias no solo revierten el stories do not simply reverse patriarchy but subvert it from patriarcado, sino que lo subvierten desde adentro. La within. -

Angela Carter (1940–92) and Japan: Disorientations

24 Angela Carter (1940–92) and Japan: Disorientations ROGER BUCKLEY Angela Carter INTRODUCTION Angela Carter (1940–92) is the subject of immense posthumous fame. Conferences, scholarly theses and literary celebrations ensure that her experimental works are widely known and carefully scruti- nized. After starting out as a journalist in Croydon, she married Paul Carter, read English at Bristol University, began writing novels (start- ing with Shadow Dance, 1965 and The Magic Toyshop, 1967) and then came to Japan as the recipient of the Somerset Maugham prize. Thereafter she divorced, remarried in 1977, taught in the United States, Australia and at the University of East Anglia, while continu- ing to publish novels, short stories and articles at a frenetic pace. Angela Carter’s growing bands of admirers view her work as a heady blend of magic realism, fantasy and purple prose. It is hardly surprisingly, they maintain, that she never won the Booker. Beachcombing for books is its own reward. So the collector patiently tells himself until he spies a nugget in the prospector’s pan and then attitudes suddenly shift. It happened when the library of my University in Tokyo was going through one of its frequent discard sales 245 BRITAIN & JAPAN: BIOGRAPHICAL PORTRAITS VOLUME VI and I found myself paying a hundred yen for a first edition of Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop. So far, so ordinary. Yet when I looked a little more carefully three cherries registered on the fruit machine’s screen; the literary equivalent of a jackpot sent silver dollars cascading onto the casino floor. -

The Ritualization of Violence in <Em>The Magic Toyshop</Em>

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons English (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-2016 The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop Victor Chalfant Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/english_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Chalfant, Victor. The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop. 2016. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000016 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop A Dissertation by Victor Chalfant Chapman University Orange, CA Department of English Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English May 2016 Committee in charge: Kevin O’Brien, Ph.D., Chair Justine Van Meter, Ph.D. Joanna Levin, Ph.D. The dissertation of Victor Chalfant is approved. Kevin O’Brien, Ph.D., Chair Van Meter, Ph.D. Joanna Levin, Ph.D. May 2016 The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop Copyright © 2016 by Victor Chalfant iii ABSTRACT The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop by Victor Chalfant This dissertation will explore the way Philip treats puppets and masks as pseudo- sacred objects in order to maintain control in Angela Carter’s work The Magic Toyshop. To show the implications of the pseudo-sacred, I will use Violence and the Sacred by Rene Girard that examines the way primitive cultures are able to maintain order through particular religious beliefs and collective violence against a scapegoat. -

Speech, Silence and Female Adolescence in Carson Mccullers’ the Heart Is a Lonely Hunter and Angela Carter’S the Magic Toyshop Catherine Martin

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 11 Issue 3 Winning and Short-listed Entries from the Article 2 2007 Feminist and Women’s Studies Association Annual Student Essay Competition Sep-2009 Speech, Silence and Female Adolescence in Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop Catherine Martin Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Catherine (2009). Speech, Silence and Female Adolescence in Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop. Journal of International Women's Studies, 11(3), 4-18. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol11/iss3/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2009 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Speech, Silence and Female Adolescence in Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop. By Catherine Martin1 Abstract This paper examines the relationship between adolescent female characters and silence in Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940) and Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop (1967). The established body of criticism focussing on McCullers’ and Carter’s depictions of the female grotesque provides the theoretical framework for this paper, as I explore the implications of these ideas when applied to language and speech.