Trans Gender Queer Sitcom History by Quinlan Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress 1-17-1991 Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991" (1991). Eastern Progress 1990-1991. Paper 16. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91/16 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1990-1991 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Activities Weekend weather Moo-ving art All together now Pressing on Friday: Dry afternoon, night low near 20. New faculty art exhibit E Pluribus Unum Colonels push Saturday and Sunday: features ceramics kicks off Monday to 2-1 in OVC Clear and dry, high of and photographs Page B-2 Page B-4 Page B-6 40. Low near 20. THE EASTERN PROGRESS Vol. 69/No. 16 16 pages January 17,1991 Student publication ot Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky. 40475 © The Eastern Progress, 1991 Middle Eastern War Zone A moment of silence Syria- Persian Gult X Mediterranean Sea Source: Cable News Network Progress grmphic by TERRY SEBASTIAN Coalition forces launch offensive on Iraqi targets War won't affect university, Funderburk says By Mike Royer, Tom Marshall middle of hell." and Joe Castle Late last night CNN reported the mission Candlelight vigil unites was "a blowout" with no allied losses, ac- It happened. cording to reports from CNN quotinq a At 7 p.m. -

Date Listed to Give Bishops Wider Power Nightmares in Vietnam

dentier ^ catholic Important . Schedule . >ubuque» la. D.P., dean of . issues in the . of Masses for 3f Theology isults of the Catholic world, edi summer are listed i change it torials and human for readers’ conven s outlook on interest features are ience this week on laity into a COLORADO’S LARGEST W EEKLY for theologi- in this issue. Page 11. Thursday, June 23, 1966 VOL. LX No. 46 in a Pres ing keynote istoral Ecu- J. Tarrant Nuns in Auto Mishap Archbishop Date Listed to Give have made Archbishop Go Home Via Airpiane church., Four Franciscan nuns injured in an automobile nenism was accident, June 8, have been released from Fort \.>^pocrijplia postles and Bishops Wider Power Morgan community hospital, Fort Morgan, and re (lought and turned to the motherhouse in Rochester, Minn., via mpport the By Patrick Riley plane this week. If I were to kick the person etary gifts, The first motu proprio on Bishops, One of the nuns, Sister Faith Huppler, received a (NCWC News Service) entitled "D e Episcoporum Muncribus,” who most frequently is res crushed right leg in the accident on Inter.state 80 S, ponsible for the miseries that Vatican City lists the dispensations reserved for the south of Fort Morgan, when a tire apparently blew recur in my life, I wouldn’t be re must be Pope Paul VI has set Aug. 15 as the Holy See under 20 headings. Among out, causing the car to skid broadside and overturn. able to sit down for a monthl oneness of these dispensations are: effective dale of the Ecumenical Council’s The lower part of Sister Faith’s leg was amputated law giving Bishops wider power to dis later at the hospital. -

CELEBRITY COLLECTORS and Their Private Collections

Universal Coin & Bullion, Ltd.TM February / March 2008 Supplement INVESTORS PROFIT ADVISORY SPOTLIGHTING OUR NEWEST COLLECTING OPPORTUNITIES CELEBRITY COLLECTORS and Their Private Collections We live in a time where there is a widespread you share a common interest. It probably comes as no fascination with fame and celebrity. To some, this surprise to anyone to know that Dick Clark, the “world’s enchantment with the personal lives of famous people oldest teenager,” has a vast collection of music borders on the obsessive. In the tabloid media, we are daily memorabilia, a large portion of which serves as treated to a litany of personal celebrity details that, more decorations for his American Bandstand Grille restaurant often than not, are scandalous in nature. Other times, when chain. Clark’s restaurants aren’t the only chain to use celebrities are doing promotional tours for their latest entertainment memorabilia collections as a lure to entice project, we usually get the canned publicity presentations customers. Worldwide chains like Hard Rock Café and intended to sell the product. Every once in a while, we catch Planet Hollywood are some of the biggest collectors of all, a personal glimpse of a celebrity that allows us to see them as they constantly search for items to adorn their theme simply as regular people, with human interests to which restaurants. These kinds of businesses, which serve as anyone of us can relate. specialized museums, give the larger public opportunities to see a wide range of collectible items they might One of the ways we can share common ground with the otherwise never get to experience. -

15 of the Most Iconic Fads from the Fifties

15 of the most iconic fads from the fifties: Car hops were THE way to get your hamburger and milkshake Hula hoops DA haircuts—yup, it stands for duck’s ass—the hair was slicked back along the sides of the head Poodle skirts are one of the most iconic fashion fads of the fifties. Invented by fashion designer Juli Lynne Charlot. Sock hops were informal dances usually held in high school gymnasiums, featuring the new Devil’s music—rock ‘n roll Saddle shoes, These casual Oxford shoes have a saddle-shaped decorative panel in the middle. Coonskin caps a major craze among young boys - a tribute to boyhood heroes of the era like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone. Telephone booth stuffing ; college students crammed themselves into a phone booth. Drive-in movies capitalized on a fortuitous merging of the booming car culture Letterman jackets and letter sweaters: high school/college girls wanted to show off they were dating a jock. Conical bras Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and Jane Russell were largely responsible for igniting the fad. Cateye glasses:the accessory of choice for many young women. Jell-O molds people took a serious interest in encapsulating various foods in gelatin. Fuzzy dice During WWII, fighter pilots hung them in their cockpits for good luck. Sideburns: a classic element of the greaser look, along with DA haircuts, bomber jackets, and fitted T-shirts with sleeves rolled up, Weeks Reached #1 Artist Single @ #1 7-Jan-50 Gene Autry "Rudolph, The Red-nosed Reindeer" 1 14-Jan-50 The Andrews Sisters "I Can Dream, Can't I" 4 11-Feb-50 -

Gunsmokenet.Com

GUNSMOKE ! By GORDON BUDGE f you had lived in Dodge City in I the 1870’s, Matt Dillon-the fic- tional Marshal of CBS Radio and TV’s Gunsmoke-would have been just the sort of man you would like to have for a friend. The same holds for his sidekick, Chester, and his special pals, Kitty and Doc. They are down-to-earth, ‘good and honest people. That one word “honest” is, to a great extent, responsible for the success of Gunsmoke on both radio and TV. It best describes the sto- ries, characters and detailed his- torical background which go to make up the show. Norman Macdonnell and John Meston, Gunsmoke’s producer and writer, are the two men who created the format and guided the show to its success (the TV version has topped the Nielsen ratings since June, 1957)) and the show is a fair reflection of their own characters: Producer Macdonnell is a straight- forward, clear-thinking young man of forty-two, born in Pasadena and raised in the West, with a passion for pure-bred quarter horses. He joined the CBS Radio network as a page, rose to assistant producer in two years, ultimately commanded such network properties as Sus- pense, Escape, and Philip Marlowe. Writer John Meston’s checkered career began in Colorado some forty-three years ago and grass- hopped through Dartmouth (‘35) to the Left Bank in Paris, school- teaching in Cuba, range-riding in Colorado, and ultimately, the job as Network Editor for CBS Radio in Hollywood. It was here that Meston and Macdonnell met. -

General Knowledge Trivia Questions Xlvii

GENERAL KNOWLEDGE TRIVIA QUESTIONS XLVII ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of these cities boasts the "Loop"? a. San Diego b. Houston c. Chicago d. Miami 2> In the 1962 film The Miracle Worker, who played the role of Helen? a. Ingrid Bergman b. Patty Duke c. Judy Garland d. Joan Bancroft 3> Whose autobiography was entitled "To Hell and Back"? a. John Wayne b. Winston Churchill c. Joseph Stalin d. Audie Murphy 4> In the card game Euchre, what is the most powerful card? a. The nine of trump b. The right bower c. The left bower d. The ace 5> Which famous person spent the majority of his life searching for the fountain of youth? a. Pissarro b. Montezuma c. Cousteau d. Ponce de Leon 6> Which famous author penned the Prince and the Pauper? a. Alexander Dumas b. Charles Dickens c. Mark Twain d. Hans Christian Anderson 7> What city would you be in if you were touring The Guggenheim? a. New York b. Paris c. Athens d. San Francisco 8> Who patented the golf tee in 1899? a. George Grant b. Arnold Palmer c. Paul Hogan d. Jack Nikolas 9> If you wanted to see Mount McKinley, which state would you have to visit? a. Montana b. Washington c. Alaska d. Colorado 10> Frankfort is the capital of which state? a. Kentucky b. Wyoming c. Idaho d. Nebraska 11> What was the name of King Arthur's sword? a. Shannara b. Almace c. Excalibur d. Curtana 12> If you were watching Olga Korburt, what sport would you be watching? a. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Download This PDF File

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2020 2020, Vol. 7, No. 3, 142-162 ISSN: 2149-1291 http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/392 Racism’s Back Door: A Mixed-Methods Content Analysis of Transformative Sketch Comedy in the US from 1960-2000 Jennifer Kim1 Independent Scholar, USA Abstract: Comedy that challenges race ideology is transformative, widely available, and has the potential to affect processes of identity formation and weaken hegemonic continuity and dominance. Outside of the rules and constraints of serious discourse and cultural production, these comedic corrections thrive on discursive and semiotic ambiguity and temporality. Comedic corrections offer alternate interpretations overlooked or silenced by hegemonic structures and operating modes of cultural common sense. The view that their effects are ephemeral and insignificant is an incomplete and misguided evaluation. Since this paper adopts Hegel’s understanding of comedy as the spirit (Geist) made material, its very constitution, and thus its power, resides in exposing the internal thought processes often left unexamined, bringing them into the foreground, dissecting them, and exposing them for ridicule and transformation. In essence, the work of comedy is to consider all points of human processing and related structuration as fair game. The phenomenological nature of comedy calls for a micro-level examination. Select examples from The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1968), The Richard Pryor Show (1977), Saturday Night Live (1990), and Chappelle’s Show (2003) will demonstrate representative ways that comedy attacks and transforms racial hegemony. Keywords: comedy, cultural sociology, popular culture, race and racism, resistance. During periods of social unrest, what micro-level actions are available to the public? Or, how does a particular society respond to inequities that are widely shared and agreed upon as intolerable aspects of a society? One popular method to challenge a hegemonic structure, and to survive it, is comedy. -

The Beverly Hillbillies: a Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968

Paul Henning; The Beverly Hillbillies: A Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968 The Beverly Hillbillies is an American situation comedy originally broadcast for nine seasons on CBS from 1962 to 1971, starring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer, Jr. The series is about a poor backwoods family transplanted to Beverly Hills, California, after striking oil on their land. A Filmways production created by writer Paul Henning, it is the first in a genre of "fish out of water" themed television shows, and was followed by other Henning-inspired country-cousin series on CBS. In 1963, Henning introduced Petticoat Junction, and in 1965 he reversed the rags The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 : A nouveau riche hillbilly family moves to Beverly Hills and shakes up the privileged society with their hayseed ways. The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 English Sub | Fmovies. Loading Turn off light Report. Loading ads You can also control the player by using these shortcuts Enter/Space M 0-9 F. Scroll down and click to choose episode/server you want to watch. - We apologize to all users; due to technical issues, several links on the website are not working at the moments, and re - work at some hours late. Watch The Beverly Hillbillies 3 Online. the beverly hillbillies 3 full movie with English subtitle. Stars: Buddy Ebsen, Donna Douglas, Raymond Bailey, Irene Ryan, Max Baer Jr, Nancy Kulp. "The Beverly Hillbillies" is a classic American comedy series that originally aired for nine seasons from 1962 to 1971 and was the first television series to feature a "fish out of water" genre. -

Calendar of Events 2017 Board Meetings Website Upgrading

Monthly Newsletter for The Tiffany Homeowners Association • A Covenant Protected Community Calendar April 2017 Vol. 12 No. 04 • Circulation: 175 of Events 2017 Upgrading Telecom Lines April 15th: Easter Egg Hunt The Xfinity/Comcast folks are upgrading the Telecom lines from Dry Creek Road 10:30 a.m. In our park to Milwaukee for the Tiffany neighborhood. They are using a horizontal directional April 22nd: Park Clean-up Day drilling, (HDD) machine to drill 4-5 feet below the ground to install new cable and con- 9:00 a.m. In our park duit. The utility easement runs behind the houses and along the property lines between May 26-29: Dumpster Days houses. The contractor should request access before entering your yard or opening a gate. The City of Centennial has issued a building permit for these folks. Call the City June 3: Spring Walk Thru of Centennial if you have any concerns or questions. June 9-10: Annual Yard Sale — Tom Wood July 4th: 4th of July Parade Starts at Milwaukee Way/ Fillmore Circle Park Clean Up Day August 13th: Neighborhood Picnic 5 p.m. In our park & Plant Swap All residents are invited to park clean-up day on Saturday April 22 at 9 a.m. We can pull weeds, pick up trash and sticks, trim bushes, and more. Does your garden need a change this Spring? Bring your unwanted perennials to Board Meetings the park during clean-up day. Trade them for plants someone else brings. Or take some June 19: Board Meeting – 6:30 p.m. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

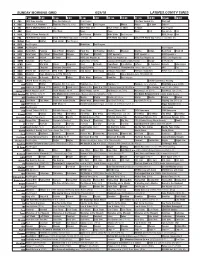

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K.