17 07 07 Issue9 LDS Page De Garde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A List of Belgian Fluorescent Minerals – from Concept to Implementation

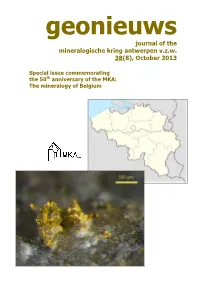

geonieuws journal of the mineralogische kring antwerpen v.z.w. 38(8), October 2013 Special issue commemorating the 50th anniversary of the MKA: The mineralogy of Belgium 1 2 3 4 1. Brookite associated with anatase. Old quarry, La Haie forest, Bertrix, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 5 mm. Collection and photo © Harjo Neutkens. 2. Anatase crystals. Les Rochettes quarry, Bertrix, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 6 mm. Collection and photo © Harjo Neutkens. 3. Bastnäsite-(Ce). La Flèche quarry, Bertrix, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 5 mm. Collection and photo © Richard De Nul. 4. Rutilated Xenotime-(Y) crystal associated with acicular rutile crystals. Old quarry, La Haie forest, Bertrix, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 3 mm. Collection and photo © Harjo Neutkens. 5. Bastnäsite-(Ce). La Flèche quarry, Bertrix, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 1.8 mm. Collection 5 and photo © Dario Cericola. Cover photo Nothing suits a Belgian golden jubilee better than Belgian gold: native gold on matrix. Sur les Roches quarry, Bastogne, Luxembourg, BE. Image width 3 mm. Michel Houssa collection, photo © Roger Warin. Mineralogische Kring Antwerpen vzw Founding date: 11 May 1963 Statutes: nr. 9925, B.S. 17 11 77 Legal address: Boterlaarbaan 225, B-2100 Deurne VAT: BE 0417.613.407 Copyright registration: Kon. Bib. België BD 3343 Periodicity: monthly, except July and August. Editor: Rik Dillen, Doornstraat 15, B-9170 Sint-Gillis-Waas. All articles (text and photos) in this (and other) issue(s) are copyrighted. If you want to use any part of this (or other) issue(s) for other purposes than your personal use at home, please contact [email protected]. -

La Plus Petite Communauté Imaginée Du Monde : Le Territoire Neutre De Moresnet Et La Transformation D'un Territoire Contesté En Nation

La plus petite communauté imaginée du monde : Le Territoire Neutre de Moresnet et la transformation d'un territoire contesté en nation The smallest imagined community in the world: The Neutral Territory of Moresnet and the transformation of a disputed territory into a nation Cyril Robelin1 Résumé Cet article propose d'étudier les différentes mutations du territoire particulier de Moresnet-Neutre. Situé près d'Aix-la-Chapelle, il a vécu, du Traité de Vienne de 1815 jusqu'au Traité de Versailles de 1919, sous la souveraineté conjointe des Pays-Bas (puis de la Belgique à partir de 1831-1839) et de la Prusse (devenue Allemagne en 1870). Le processus de l'Etat-Nation a transformé le village de Moresnet, alors territoire contesté, en un simulacre d'Etat indépendant, la plus petite des communautés imaginées. Perçu de l’extérieur, en particulier par la presse, le village est décrit comme le plus petit Etat du monde, souvent de manière artificielle. Cela se matérialise avec la construction d’un discours autour du statut de Moresnet (création de regalia et d’une rhétorique de la nation). La question des langues est centrale puisqu’on tente de la dépasser avec le projet d’un état espérantiste. Ses descriptions et ses études par les observateurs contemporains font appel à des codes sociologiques anciens (les Lumières par exemples) ou plus nouveaux. Les structures d'analyses transmises par les grands sociologues sur l’État, la Nation, la Civilisation ou l'Utopie permettent ainsi de jeter un regard nouveau sur ce territoire qui est incontestablement un objet sociologique, dont l’analyse des éléments de langage et linguistiques associés permet d’éclairer la dimension imaginaire. -

Beigeordnetes Bezirkskommissariat Eupen-Malmedy-St. Vith (1

BE-A0531_715524_715506_FRE Inventar Archivbestand Beigeordnetes Bezirkskommissariat Eupen-Malmedy-St. Vith (1. Nachtrag) (Materialien zur Ausstellung "75 jahre Belgien für die Ostkantone", 1995) Het Rijksarchief in België Archives de l'État en Belgique Das Staatsarchiv in Belgien State Archives in Belgium This finding aid is written in French. 2 Beigeordnetes Bezirkskommissariat Eupen-Malmedy-St. Vith (1. Nachtrag: Materialien zur Ausstellung "75 Jahre Belgien für die Ostkantone", 1995) (1995-1995) DESCRIPTION DU FONDS D'ARCHIVES:................................................................3 Geschichte des Archivbildners und des Archivbestands..................................4 Archivbildner................................................................................................4 Geschichte des Archivbildners.................................................................4 Archivbestand..............................................................................................4 Geschichte des Archivbestands................................................................4 DESCRIPTION DES SÉRIES ET DES ÉLÉMENTS.........................................................5 Materialien zur Ausstellung "75 Jahre belgien in den ostkantonen"................5 I. Grenzen vor 1920................................................................................................5 II. Abtretung von Eupen-Malmedy an Belgien nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg.............6 III. Grenzziehung nach 1920...................................................................................8 -

Altenberg (Moresnet-Kelmis)

1 Altenberg (Moresnet-Kelmis) Ferraris-Karte der Region Belgien (Ausschnitt) (Durch Anklicken des Plans wird die Gesamtkarte geladen) C. Rutsch schreibt in seinem Werk: Eupen und Umgebung S. 237: Das ursprüngliche Dorf bez. die Gemeinde Moresnet ist geschichtlich von nur untergeordneter Bedeutung, da dieselbe durchweg mit derjenigen der Eyneburg zusammenfällt und niemals eine eigne Herrschaft oder ein eignes Gut gebildet hat. Erst vom Jahre 1815 an hat Moresnet ein gewisses Interesse für sich in Anspruch genommen, insofern ein Zusammentreffen verschiedener Umstände eine eigentümliche Gebietstheilung herbeigeführt hat. Die Ersterwähnung der Ortsnamen Kelmis und Hergenrath stammt aus dem Jahre 1280. In einer im Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf aufbewahrten Urkunde der Zisterzienserabtei Altenkamp wird mitgeteilt, dass die Witwe und die vier Söhne des verstorbenen Aachener Bürgers Wilhelmus de Roza vor Richter und Schöffen zu Aachen ihre Erbteilung regeln. Abt und Konvent Altenkamp erhalten für den Novizen Ludovicus de Roza u.a. Erbzinsen auf Güter in „Kelms“ und „Heyenrot“. Auffallend ist, dass die damalige Schreibweise der heutigen plattdeutschen altlimburgischen Aussprache 2 "Kälemes" entspricht, insofern man voraussetzt, dass der Urkundeschreiber die stummen „e“ nicht berücksichtigt hat. Ob allerdings das Gut in „Kelms“ in einem Zusammenhang mit den Galmeigruben gestanden hat oder ob es sich hier um eine reine Ortsangabe gehandelt hat, ist ungewiss. Die Schrift Rud. Arthur Peltzer, Geschichte der Messingindustrie . in Aachen und den Ländern zwischen Maas und Rhein von der Römerzeit bis zur Gegenwart, enthält in ihren Eingangskapiteln eine ausführliche Darstellung der Frühgeschichte dieses Bergwerks. Die dort erwähnten Eintragungen in den Aachener Stadtrechnungen aus dem XIV. Jahrhundert unter Ausgaberechnung 1344 sind: Primo, Godeschalco Kremer misso bis Lymburg propter kalomynnam 1 m. -

55 the Former Lead and Zinc District of Eastern

Ann. Soc. Géol. Nord, T. 27 (2e série), p. 55-60, Novembre 2020 THE FORMER LEAD AND ZINC DISTRICT OF EASTERN BELGIUM AND THE CALAMINARIAN GRASSLANDS AFTER THE END OF EXPLOITATIONS L’ancien district plombo-zincifère de l’Est de la Belgique et les pelouses calaminaires après la fin des exploitations by Léon DEJONGHE Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Geological Survey of Belgium, 13 Jenner street, B 1000 Brussels, Belgium ; email: [email protected] Abstract In Eastern Belgium, lead and zinc deposits have been intensively exploited in the past, mainly in the XIXth century. It was one of the most important European mining areas during the Middle Ages up to the onset of the Industrial Revolution, as illustrated by paintings of Bastiné and Maugendre. This region was also the object of political tensions at the origin of the creation of the neutral territory of Moresnet. However, in spite of this importance, no attention has been provided to its geological and mining heritage after closure of the metal mines. Today, traces of the former mining exploitations nearly completely disappeared from the landscape. Calaminarian grasslands are the most visible remnants of past mining operations, sheltering an anomalous metallophyte flora. They constitute remarkable ecosystems which are now the subject of particular protection. Résumé Dans l’Est de la Belgique, les gisements plombo-zincifères ont été intensivement exploités, principalement au cours du XIXe siècle. Ils constituaient un des plus importants districts miniers européens pendant le Moyen-Âge jusqu’à l’aube de la révolution industrielle comme en témoignent les peintures de Bastiné et Maugendre.