The Last Nail in Bethlehem's Coffin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli Settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, and in the Occupied Syrian Golan

A/HRC/37/43 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 6 March 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-seventh session 26 February-23 March 2018 Agenda item 7 Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the occupied Syrian Golan Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights* Summary In the present report, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights describes the expansion of the settlement enterprise of Israel, examines the existence of a coercive environment in occupied East Jerusalem, and addresses issues relating to Israeli settlements in the occupied Syrian Golan. The report covers the period from 1 November 2016 to 31 October 2017. * The present report was submitted after the deadline in order to reflect the latest developments. A/HRC/37/43 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to its resolution 34/31, provides an update on the implementation of that resolution from 1 November 2016 to 31 October 2017. It is based on monitoring and other information-gathering activities conducted by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and on information provided by other United Nations entities in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and from Israeli and Palestinian non-governmental organizations and civil society in the Occupied Syrian Golan. It should be read in conjunction with recent relevant reports of the Secretary-General and of the High Commissioner to the General Assembly and to the Council (A/72/564, A/72/565, A/HRC/37/38 and A/HRC/37/42). -

Cremisan Valley Site Management to Conserve People and Nature

CREMISAN VALLEY SITE MANAGEMENT TO CONSERVE PEOPLE AND NATURE Prepared by Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability, Bethlehem Universitry 2021 Table of Contents Abreviations…………………………………………………………………………...…ii Executive summary……………………………………………………………………...iii 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 2 Location ....................................................................................................................... 2 3 Geology and Paleontology........................................................................................... 5 4 Flora and habitat description ....................................................................................... 6 5 FAUNAL Studies ...................................................................................................... 14 5.1 Methods .............................................................................................................. 14 5.2 Invertebrates ....................................................................................................... 17 5.3 Vertebrates ......................................................................................................... 18 5.4 Mushrooms/Fungi .............................................................................................. 22 6 Humans – Anthropolgical issues ............................................................................... 26 6.1 Cremisan Monastery ......................................................................................... -

WORSHIP CONTACT SACRAMENTS Weekday Masses Fr

19TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME, AUGUST 25, 2019 MISSION STATEMENT Faithful to the Teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, St. Raphael Parish and School promotes the Universal Call to Holiness for all the People of God. WORSHIP CONTACT SACRAMENTS Weekday Masses Fr. Michael Rudolph, Pastor x 205 Reconciliaon Monday - Saturday: 8:00 am [email protected] Weekdays: 7:30 - 7:50 am Wednesday: 6:30 am and 8:00 am Fr. Robert Aler, Parochial Vicar x 206 Saturday: 7:30 - 7:50 am, First Friday: 7:00 pm [email protected] 8:30 - 9:30 am, & 4:00 - 5:15 pm Extraordinary Form Lan Parish Email: [email protected] Marriage Weekend Masses Parish Phone: 763-537-8401 Please contact Fr. Rudolph. Saturday: 5:30 pm Parish Office Hours Bapsm Sunday: 8:30 am, 10:30 am Monday-Thursday: 8:00 am - 4:30 pm Please contact the Parish Office. Friday: 8:00 am - 12:00 pm 7301 BASS LAKE ROAD, CRYSTAL, MN 55428 | WWW.STRAPHAELCRYSTAL.ORG PASTOR’S LETTER joyful disciple of Jesus Christ. Faith Formaon to Family Discipleship… Therefore, we are making some changes in what has tradionally been called here the “Faith Formaon Who bears the most responsibility for Program.” This year, instead of weekly classes for children teaching children what it means to be a and occasional talks for their parents, we will be having Catholic Chrisan, in other words, to be a catechecal sessions for both children and their parents. disciple of Jesus Christ in the Catholic There will be a special theme for each month, which will be Church? presented and discussed on one Sunday each month, from Sacred Scripture highlights the role of parents. -

Case Study of Al Makhrour Valley

Annexing the Land of Grapes and Vines: Case Study of Al Makhrour Valley Balasan Initiative* for Human Rights is an independent, non- partisan Palestinian human rights initiative that aims to protect and promote human rights across the occupied Palestinian territory (“oPt”), indiscriminately and as set forth in international law. Through legal advocacy, research and policy planning, we seek to challenge the policies that allow the injustices to persist in the oPt. While advocating comprehensively in favor of human rights in the oPt, Balasan Initiative also aims to shed light on the effects of the current situation on the Palestinian Christian components, by creating and raising awareness on the narratives, hopes and experiences of Palestinian Christians, and the primordial objective of sustaining and solidifying their presence in their homeland, Palestine. Editor & Co-Author: Adv. Dalia Qumsieh Authors: Mr. Xavier Abu Eid, Ms. Yasmin Khamis The Balasan Initiative wishes to thank Caritas Spain, Caritas Jerusalem, Ms. Raghad Mukarker and Mr. Adham Awwad for their valuable contributions in this report. Balasan Initiative © June 2020 E-mail: [email protected] www.balasan.org *Balasan is the Arabic word (found also in the Holy Bible) for a tree that has existed in Palestine for thousands of years, which leaves were used to extract a healing balm to cure wounds and illnesses. The name is inspired by the vision that the respect for human rights and justice are a cure needed to end violations and suffering, and restore the humanity and dignity of all people. Annexing the Land of Grapes and Vines Case Study of Al Makhrour Valley 1 Introduction A haven-like valley in Beit Jala composed of plentiful agricultural terraces with irrigation systems dating back to the Roman period, and a rich biodiversity over the Western Aquifer Basin, one of Palestine’s most important water sources. -

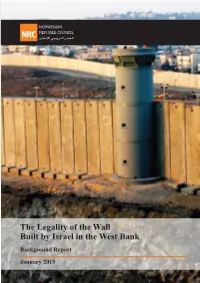

The Legality of the Wall Built by Israel in the West Bank Background Report

The Legality of the Wall Built by Israel in the West Bank Background Report January 2015 The Legality of the Wall Built by Israel in the West Bank Background Report January 2015 January 2015 Cover photo: the Wall in Qalandya area, West Bank (JCToradi, 2009). The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. This document has been produced for the NRC with the financial assistance of the UK Department for International Development. However the contents of the document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the UK Department for International Development. 2 The Legality of the Wall Built by Israel in the West Bank Background Briefing on the event of the 10 year anniversary of the ICJ decision on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory January 2015 The following report deals with issues arising from the Wall built by Israel since 2002 in the occupied Palestinian territory. It discusses the negative impact of the Wall on the life of Palestinians and their protected rights. It further examines the question of its legality, analysing the conflicting decisions of the International Court of Justice and the Israeli Supreme Court. In addition to three case studies, the potential involvement of the international community in protecting Palestinian human rights is also highlighted. 1. The Construction of the Wall and its Impact on Palestinian Life In 2002 Israel began to build a wall in the West Bank. -

Publication of the Maronite Eparchies in the USA

The Maronite Voice A Publication of the Maronite Eparchies in the USA Volume XI Issue No. VI June 2015 “Charity Begins at Home,” and So Does Mercy! ith the upcoming Holy Year, Pope Francis has asked us to take concrete steps to increase our mercy Wtowards ourselves and our families, as well as towards the Church and the world. Perhaps this may also be the time we seek the healing of some deep wounds in Church. I am speaking of the painful divisions that have harmed the Church. The Church was divided in the year 431, causing the separation of the Assyrian Church of the East. Then again we were divided in 451, with the separation of the Coptic, Armenian, and Syriac Churches (called Oriental Orthodox Churches). Division struck again in 1054, with the Eastern (Byzantine) Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. The final series of divisions took place in the time of the Protestant Reformation, with the growth of several Protestant, and later, Evangelical denominations. All these divisions continue today, but amazing progress has been made by the difficult yet persistent efforts of ecumenical dialogues. One such dialogue has produced extraordinary results, namely the Oriental Orthodox/Catholic Dialogue. Here below is the summary of that yearly joint statement. The entire text can be read at: http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/ch rstuni/anc-orient-ch-docs/rc_pc_chrstuni_doc_20150513_ exercise-communion_en.html. It is long, but it is worth the read! Summary and Conclusion 69. “The dialogue has examined in detail the nature of the relationships that existed among the member churches in the Saints Peter and Paul by Fr. -

CMEP to Sec. Kerry on Cremisan Valley

Aug 28, 2015 The Honorable John Kerry Secretary of State Dear Mr. Secretary, Churches for Middle East Peace, our coalition of 22 national church denominations and organizations -- Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant and Evangelical -- is gravely concerned at the renewed actions by Israeli authorities to build a separation barrier wall across the Cremisan Valley. The wall would separate over 50 families from the Bethlehem suburb of Beit Jala, many of whom are Christian, from their farm fields and livelihoods in the Cremisan Valley. This valley is also the location of a Catholic Monastery and a Catholic Convent that teaches children from Beit Jala. Last spring an Israeli court issued an injunction against building the wall, saying it would have an adverse impact on Palestinians. The composition of the court changed recently and it issued a new order (under appeal) allowing construction of the wall to begin, starting with the uprooting of 200 year old olive trees upon which families depend for income. This action is outrageous and gratuitous. It is gratuitous because while construction of the wall is ostensibly for security, the Cremisan Valley has been without security incident for over a decade. Defensive barriers erected on the border of nearby Israeli settlements years ago even have been taken down as unnecessary. There is no security need for this wall. This action is outrageous because it comes about because this Palestinian land happens to lie between two Israeli settlements, Gilo (located near Jerusalem) and Har Gilo (located near Beit Jala). The Israeli government is demonstrating that it values this land far more as a suburban development than working towards peace and a two-state solution. -

La Croix De Jérusalem © CTS

Les Amis des Monastères N° 194 - AVRIL 2018 - TRIMESTRIEL - 7 E Moines et moniales en Terre Sainte La Fondation des Monastères reconnue d’utilité publique (J.O. du 25 août 1974) SON BUT SA REVUE – Subvenir aux besoins des communautés Publication trimestrielle présentant : religieuses, contemplatives notamment, – un éditorial de culture ou de spiritualité ; en leur apportant un concours financier – des études sur les ordres et les et des conseils d’ordre administratif, communautés monastiques ; juridique, fiscal. – des chroniques fiscales et juridiques ; – Contribuer à la conservation du patri- – des annonces, recensions, échos. moine religieux, culturel, artistique des monastères. SES MOYENS D’ACTION POUR TOUS RENSEIGNEMENTS – Recueillir pour les communautés tous dons, Fondation des Monastères conformément à la législation fiscale sur 14 rue Brunel les réductions d’impôts et les déductions 75017 Paris de charges. Tél. 01 45 31 02 02 – Recueillir donations et legs, en franchise Fax 01 45 31 02 10 des droits de succession (art. 795-4 Courriel : [email protected] du code général des impôts). www.fondationdesmonasteres.org Les Amis des Monastères Revue trimestrielle SOMMAIRE - N°194 – Avril 2018 Moines et moniales en Terre Sainte Éditorial de Louis-Marie Coudray, osb ............................................................................ 2 Une Terre sous haute et bonne garde En couverture, La Custodie de Terre Sainte, le Patriarcat latin de Jérusalem, le Mont des Oliviers en le Consulat général de France à Jérusalem ....................................................... -

The Clockwork of Ongoing Nakba: Unraveling Forced Population Transfer

al majdalIssue No.53 (Summer 2013) quarterly magazine of BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights THE CLOCKWORK OF ONGOING NAKBA: Unraveling Forced PoPUlation transFer Ramle 1948 Naqab 2010 BADIL Resource Center publishes Israeli Land Grab and Forced Population Transfer of Palestinians: A Handbook for Vulnerable Individuals and Communities Forced population transfer is illegal and has constituted an international crime since 1942. The strongest and most recent codification of this crime is in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Rome Statute clearly defines the forcible transfer of population and implantation Jerusalem 2012 Imwas 1967 of settlers as war crimes. In order to forcibly transfer the indigenous Palestinian population, many Israeli laws, policies, and state practices have been developed and utilized. Today, Israel carries out this forcible displacement in the form of a “silent” transfer policy. The policy is silent because Israel applies it while attempting to avoid international attention by regularly displacing small numbers of people, which it presumes would go unnoticed. Israel’s legal and political structures discriminate against Palestinians in many areas including citizenship, residency rights, land ownership, and regional and municipal planning. The Handbook aims to help stymie this forced population transfer. It focuses on West Bank Area C and East Jerusalem regarding three triggers of displacement: land confiscation, restrictions on use and access of land, and the system of planning, building permits and home demolitions. The Handbook outlines Israeli state practices used to implement displacement by drawing on court decisions, legislation, military orders, and original interviews with affected individuals. They provide a much-needed practical tool for those facing possible displacement. -

Chrétiens Au Proche-Orient

Archives de sciences sociales des religions 171 | 2015 Chrétiens au Proche-Orient Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/assr/27005 DOI : 10.4000/assr.27005 ISSN : 1777-5825 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 septembre 2015 ISBN : 9-782713224706 ISSN : 0335-5985 Référence électronique Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 171 | 2015, « Chrétiens au Proche-Orient » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2017, consulté le 29 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ assr/27005 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/assr.27005 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 29 septembre 2020. © Archives de sciences sociales des religions 1 Les « chrétiens d’Orient » sont aujourd’hui au premier plan, dramatique, de l’actualité internationale. Leur histoire donne aussi lieu, depuis quelques années, à des recherches nouvelles, attentives à l’inscription de ces « communautés chrétiennes » dans leurs contextes. La sortie de l’ère postcoloniale et les crises des États-nations au Proche- Orient ont conféré une légitimité inédite à une approche des sociétés sous l’angle de leurs minorités, partant d’une nouvelle compréhension des notions de « frontières », confessionnelles ou ethniques, et des interactions entre « majorité » et « minorités ». Les contributions du présent dossier portent sur l’Égypte, la Syrie, la Jordanie et la Turquie. Ces études envisagent les chrétiens non pas comme des minoritaires victimes des aléas politiques, mais comme des acteurs participant à la vie politique, intellectuelle et culturelle de leurs sociétés. Elles éclairent les fonctionnements internes des communautés chrétiennes et de leurs institutions qui, loin de s’être fossilisées dans des traditions immuables, aménagent constamment leur rapport à l’histoire et aux langues constitutives de leur identité. -

Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 6 March 2018

A/HRC/37/43 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 6 March 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-seventh session 26 February-23 March 2018 Agenda item 7 Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the occupied Syrian Golan Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights* Summary In the present report, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights describes the expansion of the settlement enterprise of Israel, examines the existence of a coercive environment in occupied East Jerusalem, and addresses issues relating to Israeli settlements in the occupied Syrian Golan. The report covers the period from 1 November 2016 to 31 October 2017. * The present report was submitted after the deadline in order to reflect the latest developments. A/HRC/37/43 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to its resolution 34/31, provides an update on the implementation of that resolution from 1 November 2016 to 31 October 2017. It is based on monitoring and other information-gathering activities conducted by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and on information provided by other United Nations entities in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and from Israeli and Palestinian non-governmental organizations and civil society in the Occupied Syrian Golan. It should be read in conjunction with recent relevant reports of the Secretary-General and of the High Commissioner to the General Assembly and to the Council (A/72/564, A/72/565, A/HRC/37/38 and A/HRC/37/42). -

Bishops Urge Action on Confiscation of Cremisan Valley

Committee on International Justice and Peace 3211 FOURTH STREET NE • WASHINGTON DC 20017-1194 • 202-541-3160 WEBSITE: WWW.USCCB.ORG/JPHD • FAX 202-541-3339 January 28, 2014 The Honorable John Kerry Secretary of State 2201 C St NW Washington, DC 20520 Dear Secretary Kerry: As Chair of the Committee on International Justice and Peace of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, I wrote you last May regarding the injustice being perpetrated in the Cremisan Valley near Bethlehem in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Earlier this month, I made a solidarity visit to the Cremisan Valley together with brother bishops from Europe, Canada and South Africa. Enclosed you will find a statement that summarizes our reflections on the sad state of affairs. As I stood amidst the beauty of this agricultural valley and heard the testimony of the Christian families whose lands, livelihoods, and centuries-old family traditions are threatened, I was simply astounded by the injustice of it all. On the eve of the Supreme Court of Israel taking up this case, I ask you once again to urge the Government of Israel to cease and desist in its efforts to unnecessarily confiscate Palestinian lands in the Occupied West Bank. As I said earlier, the Cremisan Valley is a microcosm of a protracted pattern that has serious implications for the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict and your commendable efforts to achieve a peace agreement. Sincerely yours, Most Reverend Richard E. Pates Bishop of Des Moines Chairman, Committee on International Justice and Peace United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Encl.