A Literary Pilgrimage and a Collection of Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

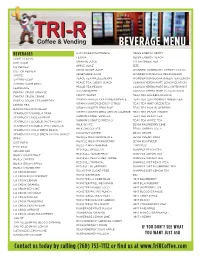

Beverage Menu

BEVERAGE MENU BEVERAGES GATORADE FRUITPUNCH REIGN ENERGY BERRY TEJAVA REIGN ENERGY PEACH COKE CLASSIC ORANGE JUICE ITO EN GREEN TEA DIET COKE APPLE JUICE IZZE DR PEPPER CRAN GRAPE JUICE WONDER KOMBUCHA CHERRY CASSIS DIET DR PEPPER VEGETABLE JUICE WONDER KOMBUCHA PEAR GINGER SPRITE PEACE TEA RAZELEBERRY WONDER KOMBUCHA GREEN TEA LEMON CHERRY COKE PEACE TEA CADDY SHACK GUAYAKI YERBA MATE LEMON ELATION CHERRY COKE ZERO PEACE TEA PEACH GUAYAKI YERBA MATE ENLIGHTEN MINT LEMONADE DASANI WATER GUAYAKI YERBA MATE CLASSIC GOLD FANTA/ CRUSH ORANGE SMART WATER TEAS TEA GOLDEN OOLONG FANTA/ CRUSH GRAPE VITAMIN WATER XXX POMEGRANATE TEAS TEA LEMONGRASS GREEN TEA FANTA/ CRUSH STRAWBERRY VITAMIN WATER ENERGY CITRUS TEAS TEA MINT GREEN TEA LEMON TEA VITAMIN WATER ZERO RISE TEAS TEA POM. BLUEBERRY BARQS/MUG ROOTBEER VITAMIN WATER ZERO LEMON SQUEEZE TEAS TEA PEACH GINGER STARBUCK'S VANILLA FRAP DUNKIN DONUT VANILLA TEAS TEA BLACK TEA STARBUCK'S MOCHA FRAP DUNKIN DONUT ESPRESSO TEAS TEA WHITE TEA STARBUCK'S DOUBLE SHOT MOCHA MILK WHITE ZEVIA RASPBERRY LIME STARBUCK'S DOUBLE SHOT VANILLA MILK CHOCOLATE ZEVIA CHERRY COLA STARBUCK'S COLD BREW BLACK COCONUT WATER ZEVIA GRAPE STARBUCK'S COLD BREW COCOA HONEY MUSCLE MILK CHOCOLATE ZEVIA CREAM SODA PEPSI MUSCLE MILK STRAWBERRY ZEVIA ROOTBEER DIET PEPSI MUSCLE MILK BANANA LIMITLESS MTN. DEW RED BULL REGULAR SNAPPLE PEACH TEA GINGER ALE RED BULL SUGAR FREE SNAPPLE LEMON TEA BUBLY GRAPEFRUIT RED BULL PEACH-NECTARINE SNAPPLE MANGO TEA BUBLY CHERRY RED BULL TROPICAL SNAPPLE DIET PEACH TEA BUBLY GREEN APPLE RED BULL -

2019-2020 Suite Menu (Pdf)

ADVANCED MENU BUFFETS & COMBOS BUFFETS | Priced per person with a minimum order of 14. THE BREAK AWAY | $17.50 Garlic Parmesan Chicken Drumsticks, Country Fried Ribs and Brisket served with Smokehouse BBQ Sauce, Tea Buns, Zesty Aioli Slaw, House-Made Potato Chips NEW PASTA | $16.50 Beef Brisket Ravioli in Mushroom Wine Sauce, Ricotta Stuffed Shells in Marinara with a DECC Pesto Drizzle, Caesar Salad, Garlic Breadsticks, Grated Parmesan Cheese, Cracked Pepper BBQ SHREDDED PORK | $16.50 Sesame and Whole Wheat Buns, Sliced Cheddar and Provolone Cheese, Fresh Vegetables with Dip, House-Made Potato Chips PIZZA | $14.25 Thin Crust 16 Inch House-Made Pizza One Pepperoni, One Buffalo Chicken, One Cheese, One Veggie Shakers of Parmesan Cheese and Crushed Red Pepper, Fresh Vegetables with Dip, Fresh Cut Fruit NACHOS | $16.50 Fresh-Made Crispy Tortilla Chips, Ground Beef and Shredded Chicken, Diced Fresh Tomatoes, Onions, Spicy Cheese Sauce, Black Olives, Jalapeno Peppers, Chunky Salsa, Sour Cream, Fresh Vegetables with Dip COMBOS | Serve 14 guests. POWER PLAY ASSORTMENT | $170 Mango Habanero and Smokehouse BBQ Meatballs (14 each), Garlic Parmesan and Sweet Chili Chicken Drumsticks (14 each), Chicken and Beef Mini Tacos (14 each) served with Cilantro Lime Sour Cream CHEESE AND SALAMI ASSORTMENT | $143 Cubed Cheeses, Salami, Pepperoni, Fraboni’s Wild Rice Pork Sausage, Pretzel Bites (14), Pickles, Olives DECC CHILI BAR | $97 DECC Award Winning Chili served with Cavatappi Noodles, Fritos Corn Chips, Sour Cream, Grated Cheese THE WILD BAR | $127 Grandma’s Chicken Wild Rice Soup Served with Great Harvest French Bread, Fraboni’s Wild Rice Pork Sausage, Cubed Wisconsin Cheddar TAILGATE SAMPLER | $282 Hat Trick Wings, BBQ Meatballs, Wisconsin Classic Cheese Board, Taco Dip with Tortilla Chips SLAP SHOT SAMPLER | $310 Platter of Each: Bruschetta, Northern Waters Smokehaus Salmon, Wisconsin Classic Cheese Board, Fresh Vegetables with Dip 1 PRICES SUBJECT TO TAXES AND 17% TAXABLE SERVICE CHARGE ADVANCED MENU HOT HORS D’OEUVRES Serves 14 guests. -

New Products and Promotions

Fusion Gourmet USA NEW PRODUCTS Dolcetto Wafer Rolls, made from all natural ingredients, AND PROMOTIONS are light and crispy on the out- side with a creamy filling. Fla- vors include Tiramisu, Choco- late and Cappuccino. They come packaged in a 14.1 oz vintage-style tin and are available in shippers. Tel: +1 (310) 532 8938 www.fusiongourmet.com Impact Confections, Inc. USA Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. USA Warheads Double Drops is a supersour candy liq- uid with two flavors in a two-chamber, dual- dropper bottle. Enjoy one flavor at a time or both. Flavor combos include green apple/ watermelon, blue raspberry/green apple and watermelon/blue raspberry. Available in a Orbit White Wintermint is a new fla- 24-count display with an srp of 99¢. vor of the teeth-whitening, stain- Warheads Juniors removing Orbit gum. Extreme Sour hard Eclipse Cinnamon Inferno and candy is a miniature Midnight Cool are two new fla- version of the original Extreme vors of Eclipse breath-freshening Sour candy in a sleek dis- gum. penser, with an assortment of five Altoids Mango Sours are a new sour flavors for mix-and-match flavor sensation and control fruit flavor Altoids hard candy. of sour intensity. Flavors include apple, black cherry, Extra Cool Watermelon is a blue raspberry, lemon and watermelon. Ships in an 18- new flavor addition to Extra count display with an srp of 99¢. gum. Tel: +1 (719) 268 6100 www.impactconfections.com Doublemint Twins Mints, an extension of the Dou- Van Damme Confectionery, Inc. USA blemint brand, come Van Damme has introduced All in two flavors, Winter- Natural Marshmallow Cubes, a mix creme and Mintcreme. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Meal Replacement Shakes $6.00 COMBOS PROTEIN

COMBOS SOME OF OUR SHAKES ARE MADE WITH PEANUTS OR TREE NUTS. PLEASE LET US KNOW OF ANY FOOD ALLERGIES. Step 1 - PICK YOUR SHAKE Meal Replacement Shakes $6.00 Step 2 - PICK YOUR BEVERAGE 16oz Healthy meal, 24g Protein, 21 Vitamins and Minerals, 200-350 Calories Level 1 ($8.00) Meal Replacement Shake & Level 1 Energy Drink THE TOP 10 CHOCOLATE 24g Protein, 200-250 Cal., 5g Sugar, 6g Fiber Banana Nut Bread Butterfinger Level 2 ($11.00) Fried Ice Cream Snickers Meal Replacement Shake & Level 2 Energy Drink Orange Dreamsicle $ S’mores 24g Protein, 200-250 Cal., 5g Sugar, 6g Fiber Peanut Butter Cup Ferrero Rocher Turtle Cheesecake Level 3 ($12.50) Samoa Meal Replacement Shake & Level 3 Energy Drink Peanut Butter Waffle Mudslide 24g Protein, 200-350 Cal., 5g Sugar, 6g Fiber Blueberry Muffin No Bake Cookie Java Lava Pre Workout Combo ($8.00) Puppy Chow Prepare - Caffeine, Nitric Oxide, Creatine, Brownie Batter Red Velvet Bioavailable electrolytes Lemon Pound Cake Chocolate Covered Cherry Thin Mint Post Workout Combo ($9.00) VANILLA 24g Whey Protein Shake, BCAAs, L- Cookies N’ Cream Chocolate Praline Glutamine, Tri Aminos & Level 1 Drink Bit-O-Honey Twix Cookie Dough Substitute our Certified Vegetarian Key Lime $ PEANUT BUTTER line for an additional $2.00 Wedding Cake Peanut Butter Banana CHILDREN’S MENU Cinnamon Toast Cheesecake Banana Fosters Pina Colada Peanut Butter Cheesecake Oatmeal Cookie Peanut Oatmeal Cookie Smoothie ($5.00) Cinnamon Roll 12oz Healthy Smoothie of your choice Nutter Butter Butter Pecan Payday Apple Pie $ Peanut Brittle -

FOOD TYPE RED GREEN Baby Food & Formula Baking & Cakes Bread Butter and Margarine

FOOD TYPE RED GREEN Heinz for Baby Baby Food & Anmum Heinz Nurture Formula Formula Holle NESTLÉ NESLAC Toddler Gold Morganics-baby ‘O’ Organic Bubs Nutricia Rafferty’s Garden Tatura Infant Formula Bakers Delight Carte D’Or Baking & Betty Crocker Clive of India Big Sister Foods Country Life Cakes Bourneville cacao Crispix Cadbury baking Easy Bakers Gluten Free Cake Mate Edmonds Cereform Eggo Croissant King Ernest Adams Flake cooking chocolate Flora Real Ease Fowlers Vacola Fudge shop General Mills Greens George & Simpson JJ’s Bakehouse Nestle Choc Bits Keebler Holland House Cakes Kellogg Maypole Foods Kialla Pure Foods McCormick Laucke Flour Nestle Baking Cocoa Naturally Good NESTLÉ PLAISTOWE McKenzie’s Weston Cereal Industries Orgran Baking and Bread Mixes Pampas Quality Desserts Queen Fine Foods (Vanilla Essences & Rainbow Food Colours) Ward McKenzie Water Grain White Wings Baker’s Delight Bill’s Organic Bread Bread Burgen Country Life General Mills Diego’s Flour Tortilla Noble Rise Flinders Bread Pillsbury Freyas Tip Top Helga’s Van den Bergh’s La Famiglia La Tartine Leaning Tower MacKenzie High Country Bread Mighty Soft Molenberg Natures Fresh Pure Life Sprouted bread Quality Bakers San Diego Corn Tortilla Souvlaki Hut Vogel’s Western Bagels Wonderwhite Allowrie Dairy soft Butter and Country Gold Goldn Canola Girgar Flora margarine Mainland Logicol Naytura (Woolworths) Meadow Lea Weight Watchers Canola Spread Melrose Omega Gold Western Star Nuttelex Olive Grove Tablelands Tatura 2 Bamboo Pot Asia@Home Canned Birds Eye Blue Kitchen Gourmet -

The Truefood Guide Is Your Shopping List for Healthy, GE-Free Food

The Truefood Guide is your shopping list for healthy, GE-free food Australia has very limited laws for the labelling of genetically engineered (GE) foods. That’s where the Truefood Guide comes in. The Guide rates food brands and products as Green (GE-free) or Red (may contain GE ingredients). ✔ Buy Green Brands and products in the green section have policies and procedures throughout their supply chain to actively avoid ingredients derived from GE crops. ✘ Avoid Red Brands and products in the red section of the Guide may contain ingredients derived from GE crops. GE crops were introduced in Australia in 2008. GE canola is now commercially grown in NSW and Victoria. Canola is found in many pantry foods from margarine and vegetable oil, to ice-cream, breads and sauces. Ingredients derived from soy, maize and cottonseed are also in many food products in Australia. Most Australians do not want to eat GE food. Many food companies are responding to consumer demands by removing GE ingredients from their products. You can help by asking copanies with red-listed brands to adopt a non-GE policy. For further information, visit www.truefood.org.au True Food Guide proudly supported by the Melbourne Community Foundation rmg account. 23 March 2009 2:10 PM GE free ✔ May contain GE ✘ Green GE-free brands are rated green. Red Brands that may include GE-derived These companies have a clear policy on ingredients in their products are rated red. excluding GE-derived ingredients, including This includes brands that either: oils derived from GE crops, and animal • contain GE derived ingredients; and/or products from animals fed on GE crops. -

Menus to Choose from We Are Fort Wayne’S Premier Restaurant Food Delivery Service

What is Waiter on the Way? Menus to choose from We are Fort Wayne’s premier restaurant food delivery service. We make it convenient to have 800° Pizza ....................1 Dunkin’ Donuts ..........57 Oley’s your favorite meals from Fort Wayne’s favorite 816 Pint & Slice ...........2 Elmo’s Pizza ...............57 Pizza Shoppe ............120 restaurants delivered to your home or office without all the hassle and effort of doing it Agaves Mexican Grill ..2 Enzo Pizza ..................58 Panda Express ..........121 yourself. We can cater your business meetings, Auntie Anne’s...............5 Famous Fish of Stroh .59 Papa Johns ................121 office parties, dinner parties or any other meal- Bagel Station ................5 Fazoli’s .......................61 Penn Station time gathering that you don’t wish to prepare yourself. We bring the restaurant to you! Baskin Robbins ............8 Flanagan’s ..................62 East Coast Subs ........122 Biaggis .........................8 Fortune Pho 888 ....................122 Business Hours: Big Apple Bagels ....... 11 Chinese Buffet............65 Pine Valley Monday-Friday 8:00am - 10:00pm Big Eyed Fish .............12 Four Seasons Bar & Grill ...............124 Saturday 11:00am - 10:00pm Black Dog Pub ...........13 Family Restaurant ......67 Qdoba .......................126 Sunday 12:00 noon - 9:00pm Blue City Tavern ........14 Golden China .............70 Qui’s .........................127 Buckets Sports Granite City ................72 Quizno’s ...................132 Deliveries outside office -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Homecoming 2011: Volume 55 Issue 2 P

Bishop Miege High School In the Miegian... p. 4 Mike McCoy Homecoming 2011: Volume 55 Issue 2 p. 9 KC’s Best Pizza October 2011 ‘Making Memories of Us’ p. 10 Remembering Steve Jobs - cover photo by Brooke Bradshaw - back page photos by Jordan Tucker, Molly Amey, and Brooke Bradshaw The Miegian Miegians Make Memories at Homecoming Stuco’s Annual Food-raiser Get Your Tickets Before Treats the Area’s Hungry By: BenHire One of the most exciting ing queen at the football game dur- News aspects of Homecoming is always ing halftime when last year’s queen, By: KarlNetermeyer ”Trick or Treat So Others Can Eat” has ‘Annie Gets Her Gun’ staff writer the announcement of Homecoming Judith Navarro, passed on the ti- students go door-to-door in costumes queen. The candidates were seniors ara. staff writer and ask not for candy, but canned Homecoming. Aside from Molly Jackson, Kelsey Ludwig, Claire Another enjoyable element of goods from their respective parishes. Every Oct. 31, children all Prom, it may be the biggest social Mitchell, Kristen Pearson and Liz Homecoming is the dinner before the The “trick or treaters” then bring their around the country set out in cos- event of the en- dance. Usu- cans back to Miege and fill up the Har- tumes to participate in the ageless tire school year. ally, couples vester’s truck. Many parishes partici- ritual of trick-or-treating. Most chil- Guys have a will take their pate in the event, such as St. Agnes, St. dren will go out and come home with chance to ask the pictures and Ann’s, and St. -

VS Web Pricebook Candy

SNACKS Products Manufactured By - MARS SNACKFOOD 0.00 560‐471 COMBOS CHEDDAR PRETZEL 216 71471 560‐472 COMBOS NACHO PRETZEL 216 71472 560‐473 COMBOS PEPPERONI CRACKER 216 71473 560‐475 COMBOS PIZZERIA PRETZEL 216 71475 CANDIES Products Manufactured By - BOYER BROS. INC. 0.00 505‐038 BOYER MALLO CUPS 72 12138 505‐238 BOYER SMOOTHIE CUP 72 12238 Products Manufactured By - CADBURY ADAMS USA LLC 0.00 570‐900 SWEDISH FISH 2 OZ 288 1506206 570‐905 SOUR PATCH KIDS 2 OZ 288 1506201 570‐908 SOUR PATCH KIDS PEG BAG 5 OZ 12 Products Manufactured By - CHARMS 0.00 510‐246 SUGAR BABIES 144 53320 Products Manufactured By - FARLEY'S & SATHERS 0.00 525‐110 F&S GUM DROPS 10 OZ 12 23110 525‐231 F&S ORCHARD FRUIT SNACKS 48 30064351 525‐334 HAW PUNCH FRT SNACKS 2.25 OZ 48 30040334 525‐366 F&S STARLIGHT MINTS 5.5 OZ 12 23366 525‐469 F&S CHERRY SOURS 5.5 OZ 12 23469 525‐500 F&S NOW & LATER ORIGINAL 12/24 288 500670 525‐504 NOW&LATER TROPICAL 12/24 288 500631 525‐506 NOW&LATER SOFT ASSORT 12/24 288 559100 525‐950 F&S CHUCKLES 288 170950 Products Manufactured By - GOETZE'S 0.00 530‐101 GOETZE CARAMEL CREME 2/48 96 20101 Products Manufactured By - GOLDEN GROVE CANDY CO. 0.00 532‐201 GGC CAROLINA CRISP PNUT BAR 48 00201 CANDIES Products Manufactured By - HERSHEY 0.00 536‐002 LSC KITKAT BAR 2.05 OZ 216 24672 536‐005 LSC REESES PBC 3‐PACK 240 44251 536‐007 LSC WHATCHAMACALLIT 2 OZ 240 24771 536‐008 LSC PAYDAY 216 80710 536‐012 LSC HERSH MILK CHOC/ALMND 216 27121 536‐021 LSC ALMOND JOY 2.0 OZ 216 02623 536‐045 ZERO 1.85 OZ 288 COUNT 288 80415 536‐060 REESES PNUT BUTTERCUP -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun