Sam Stemm Oral History Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA GUIDE Television • Radio • Wire Services • Illinois Publications • Missouri Publications • Online •

2011 MEDIA GUIDE Television • Radio • Wire Services • Illinois Publications • Missouri Publications • Online • • Phone • Fax • Email • Address • Contact www.stl.unitedway.org 2011 ST. LOUIS METRO AREA MEDIA GUIDE The 2011 edition of the St. Louis Area Media Guide has been prepared for use by United Way member agencies and other not-for-profit human service organizations throughout the greater St. Louis area. The mediums listed have been contacted to assure that listings are complete and current. Please be advised that changes occur rapidly within the guide. Let us know if you have updates, additions or corrections to suggest. If you are an affiliated United Way agency, the United Way Communications Department staff is available to help with your communications programs. For more information, please contact the Communications Department at 314-539-4073. Cost: The Media Guide may be mailed or sent electronically in pdf format for $20. One copy is free to each United Way member/partner organizations. For the latest information on United Way, visit our Website at: http://www.stl.unitedway.org Sincerely, Communications and Brand Marketing United Way of Greater St. Louis Inclusion of media outlets within does not imply endorsement. Exclusion of any media outlets is simply an oversight. Media may contact the Communications Department of United Way to be included by calling 314-539-4029 or emailing: [email protected] THE UNITED WAY 2011 AREA MEDIA GUIDE About United Way of Greater St. Louis: Mission Statement United Way of Greater St. Louis unites people of diverse backgrounds and interests who work together to strengthen health and human services in Missouri and Illinois. -

Intern Hosts 2009

RECOMMENDED INTERN HOSTS 2010 Steps in setting up your internship: 1. First, remember that internship course credit is reserved for senior Mass Communications majors only. If you wish to do an internship before you’re a senior, you’ll receive no credit, but it’s still a great thing to do for the experience. 2. Consult the flyers that promote newer internships (found on the Internship bulletin board) along with this list of internships that previous interns have recommended to research and narrow down your prospects. Then go to see your Mass Comm. Dept. advisor to get his/her advice about whether the prospects you’ve selected are right for you. Get your advisor’s help in ranking your prospects. Don’t skip this step! You’ll be surprised how helpful your advisor will be to narrow down your short list to the best for you. 3. Read internship FAQs found on our website, <www.siue.edu/MASSCOMM/internship.html> Pick up or download a copy of the latest MC 481 syllabus from this site so you know what’s required. Check out resume and cover letter writing handout, etc., also found at our Internship website. Then you’ll understand what’s required. And in case it comes up in your internship job interview, you will know and can share the information on the syllabus. 4. Contact your number one and two choices. Do NOT send out a dozen query letters or call several internship venues. If there’s one kind of prospective intern they all hate, it’s the internship “shopper.” They don’t want to waste their time interviewing and considering hiring people who are not serious. -

The Press Club of Metropolitan St. Louis 2008 Media Guide and Membership Directory ______

___________________________________________________ The Press Club of Metropolitan St. Louis 2008 Media Guide and Membership Directory ___________________________________________________ From the President Alice S. Handelman The Press Club of Metropolitan St. Louis is pleased to publish the 2008 edition of our Media Guide and Directory as a service to our members and the general public. Each year, the Press Club provides valuable internships and scholarships to promote young journalists. We also offer a variety of interesting and informative forums on topics of current interest, utilizing local talent to inform and educate the public. We honor one of the greats in our field annually with the Media Person of the Year award and, when appropriate, award the Jack Buck National Media Person of the Year honor. Press Club funds maintain the Media Archives at the St. Louis Public Library with support and administration of library staff. Press Club members serve on the advisory board of the Media Halls of Fame at The Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. We hope that you will find this St. Louis Area Metro Area Media Guide and Press Club Membership Directory helpful to access information and contact fellow journalists and other communications professionals. It is also available and updated online to members at our website: http://www.stlpressclub.org. For password access, contact Press Club at 636-230-1973. ____________________________________________________________________ The Press Club of Metropolitan St. Louis Website: www.stlpressclub.org Office: Logan University Mailing Address: PO Box 410522 Administrative Building St. Louis, MO 63141 Room 111 Phone: 636-230-1973 1851 Schoettler Road FAX: 636-207-2441 or 2424 Chesterfield, MO 63017 Email: [email protected] Special thanks to the University of Missouri-St. -

For a Comprehensive List of the Events Occuring at the St. Mary's Oktoberfest 2015, Click Here

Grounds Open Friday, October 9, 6pm to 11pm ● Saturday, October 10, 1pm to 11pm ● Sunday, October 11, Noon to 10pm Mass Times for the Oktoberfest Anniversary Celebration Saturday, October 10 – Vigil Mass in the Church at 5:15pm Sunday, October 11 – Mass in the Church at 6:30am & 8:00am Sunday, October 11 - “Mass in the Grass” Garfield Park at 11:00 (6th & Langdon) Bring a lawn chair or blanket *Please note: There is no 9:30am or 6:00pm Sunday Mass Live Music Schedule Friday 7 – 11 pm - Glendale Riders – Main Stage Saturday 1 – 4 pm – St. Louis Czech Express – Main Stage 2 – 5 pm – Dixie Dudes – Festival Stage 6:30 – 10:30 pm – The Owlz – Festival Stage 7 – 11 pm – Baywolfe – Main Stage Sunday 12:30 – 4:30 pm - Big Shake Daddies – Festival Stage 12:30 – 4:00 pm – St. Louis Czech Express – Main Stage 4 – 6 pm – Harman Family Band – Auction Tent on 3rd St. 6:30 – 10:00 pm - Back in the Saddle – Main Stage MAIN STAGE: 3rd & Langdon Sts. FESTIVAL STAGE: 3rd & Henry Sts. AUCTION TENT ON 3rd ST: near Langdon St. www.stmarysoktoberfest.com Guten Tag! Oktoberfest kicks off with a keg tapping ceremony on the Main Stage at 1pm on Saturday. It is Oktoberfest tradition that the beer is free until the first keg runs dry! 33’ SCREEN AVAILABLE ALL 3 DAYS FOR BASEBALL POSTSEASON GAMES! $10,000 Sweepstakes Raffle! Details and Tickets for sale on the festival grounds To be drawn 8pm Sunday at Main Stage. Need not be present to win. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Quick Facts TABLE of Contents

FOOTBALL QUICK FACTS Illinois Athletic Communications // 217-333-1391 // www.fightingillini.com/media Football Co-Contacts: Kent Brown ([email protected]) and Derek Neal ([email protected]) UNIVERSITY INFORMATION Location: Urbana-Champaign Founded: 1867 2014 ILLINOIS SCHEDULE Enrollment: 44,942 DATE OPPONENT TIME LOCATION 2013 REC SERIES HISTORY (LAST) Colors: Orange & Blue Aug. 30 YOUNGSTOWN STATE 11 am CT MEMORIAL STADIUM 8-4 First Meeting Nickname: Fighting Illini Sept. 6 WESTERN KENTUCKY 11 am CT MEMORIAL STADIUM 8-4 First Meeting Conference (Division): Big Ten (West) Sept. 13 at Washington 3 pm CT Seattle, Wash. 9-4 WASH leads 6-4 (2013) President: Robert Easter Sept. 20 TEXAS STATE TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 6-6 First Meeting Phyllis Wise Chancellor: Sept. 27 at Nebraska 8 pm CT Lincoln, Neb. 9-4 NEB leads 8-2-1 (2013) Director of Athletics: Mike Thomas Oct. 4 PURDUE TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 1-11 ILL leads 43-40-6 (2013) Stadium: Memorial Stadium (FieldTurf – 60,670) Oct. 11 at Wisconsin TBA Madison, Wis. 9-4 WIS leads 37-36-7 (2013) Oct. 25 MINNESOTA (Homecoming) 11 am CT MEMORIAL STADIUM 8-5 MIN leads 35-28-3 (2012) COACHING STAFF Nov. 1 at Ohio State 7 pm CT Columbus, Ohio 12-2 OSU leads 66-30-4 (2013) Head Coach: Tim Beckman Nov. 15 IOWA TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 8-5 ILL leads 38-29-2 (2008) Alma Mater: Findlay, 1988 Nov. 22 PENN STATE TBA MEMORIAL STADIUM 7-5 PSU leads 17-4 (2013) Record at Illinois: 6-18 (2 seasons) Nov. 29 at Northwestern TBA Evanston, Ill. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Postcard Data Web Clean Status As of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amoun

postcard_data_web_clean Status as of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amount 33080 DDKVIK FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 IA DECORAH 0641 575 13550 DKABN AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million CA CONCORD 0627 3100 60843 DKHOS AM Station Licensed B up to 25,000 TX SONORA 0623 500 35480 DKKSL AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million OR LAKE OSWEGO 0627 3100 2891 DKLPL-FM FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 LA LAKE PROVIDENCE 0641 575 128875 DKPOE AM Station Const. Permit TX MIDLAND 0615 395 35580 DKQRL AM Station Licensed B 150,001 - 500,000 TX WACO 0626 2025 30308 DKTRY-FM FM Station Licensed A 25,001 - 75,000 LA BASTROP 0642 1150 129602 DKUUX AM Station Const. Permit WA PULLMAN 0615 395 50028 DKZRA AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 TX DENISON-SHERMAN 0625 1200 70700 DWAGY AM Station Licensed B 1,200,001 - 3 million NC FOREST CITY 0628 4750 63423 DWDEE AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MI REED CITY 0635 475 62109 DWFHK AM Station Licensed D 25,001 - 75,000 AL PELL CITY 0636 725 20452 DWKLZ AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 MI KALAMAZOO 0625 1200 37060 DWLVO FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 FL LIVE OAK 0641 575 135829 DWMII AM Station Const. Permit MI MANISTIQUE 0615 395 1219 DWQMA AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MS MARKS 0635 475 129615 DWQSY AM Station Const. -

2018 SLIFF Media Report

MEDIA OUTREACH Included in monthly event emails to long lead media (July – November) Included in weekly event emails to media (October 15 – November 5) August – sent to media for Fall Arts Events Previews 9/25 – Goodman release sent wide 10/9 – Full festival release sent wide 10/12 – invitation to cover opening night sent to select media outlets 10/16 – list of interviews available for visiting filmmakers/talent sent wide to media 10/16 – pitched radio stations for promotional giveaways of festival passes 10/18 – began doing individual outreach for interviews 10/19 – began pitching niche media for interviews (ie: music, Asian, Environment, LGBTQ, kids/family, Hispanic, African-American) 11/1 – 11/11 – Daily alerts of events set to assignment/news desk each morning 11/2 – link to download images of Kusama event sent to media 11/3 – link to download images of Goodman event sent to assignment desks 11/3 – link to download video of Goodman event sent to Fox2 assignment desk (exclusive) 11/4 - link to download video of Goodman event sent to assignment desks 11/8 – link to download photos and video of Edwards tribute sent to media 11/12 – list of award winners sent wide to all media PRINT Alive Magazine Requested interviews with Kusama and Reitman, forwarded to Allied 10/30 What to Do in St. Louis This Weekend mention http://alivemag.com/what-to-do-in-st-louis-this-weekend-19/ 10/30 “This Year’s Impressive Lineup at the St. Louis International Film Festival” http://alivemag.com/this-years-impressive-lineup-at-the-st-louis-international-film-festival/ -

Incomplete List of Internship Hosts Steps in Setting up Your Internship (Start Early)

Updated 7/2016 Incomplete list of Internship Hosts Steps in setting up your internship (start early): 1. First, remember that internship course credit is reserved for senior Mass Communications majors only. If you wish to do an internship before you’re a senior, you cannot receive credit from this department. Still, it’s a great thing to do, just for the experience and the contacts. 2. Read the internship FAQ found on our website www.siue.edu/MASSCOMM. On this same website, download a copy of the latest MC 481 syllabus so you know what’s required and how things work and check out the resume and cover letter writing handout, the Portfolio Instructions handout, etc. Then you’ll understand what’s required. 3. You can intern almost anywhere (company and/or location) as long as it meets the requirements: you’re able to get 225 hours and your supervisor has experience in that area. For example, if you’re doing a video internship, your supervisor must have video experience. This is so that 1) you’ll be able to learn from this person, and 2) this person will be able to evaluate your performance. An example of something that wouldn’t work would be if a local business wanted a video intern to produce videos because no one at the business had that experience. This would not count for an internship. 4. Think about the kind of place you may want to work (or even the specific companies). Look into getting an internship at that company or a company within that specific industry. -

Location Indicators by State

ECCAIRS 4.2.8 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by State The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 17 September 2010 Page 1 of 123 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by State Data Definition Standard 0100 Afghanistan 1060 OAMT OAMT : Munta 1061 OANR : Nawor 1001 OAAD OAAD : Amdar OANR 1074 OANS : Salang-I-Shamali 1002 OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi OANS 1062 OAOB : Obeh 1003 OAAS OAAS : Asmar OAOB 1090 OAOG : Urgoon 1008 OABD OABD : Behsood OAOG 1015 OAOO : Deshoo 1004 OABG OABG : Baghlan OAOO 1063 OAPG : Paghman 1007 OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan OAPG 1064 OAPJ : Pan jao 1006 OABN OABN : Bamyan OAPJ 1065 OAQD : Qades 1005 OABR OABR : Bamar OAQD 1068 OAQK : Qala-I-Nyazkhan 1076 OABS OABS : Sarday OAQK 1052 OAQM : Kron monjan 1009 OABT OABT : Bost OAQM 1067 OAQN : Qala-I-Naw 1011 OACB OACB : Charburjak OAQN 1069 OAQQ : Qarqin 1010 OACC OACC : Chakhcharan OAQQ 1066 OAQR : Qaisar 1014 OADD OADD : Dawlatabad OAQR 1091 OARG : Uruzgan 1012 OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof OARG 1017 OARM : Dilaram 1016 OADV OADV : Devar OARM 1070 OARP : Rimpa 1092 OADW OADW : Wazakhwa OARP 1078 OASB : Sarobi 1013 OADZ OADZ : Darwaz OASB 1082 OASD : Shindand 1044 OAEK OAEK : Keshm OASD 1080 OASG : Sheberghan 1018 OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem OASG 1079 OASK : Serka 1031 OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala OASK 1072 OASL : Salam 1047 OAFG OAFG : Khost-O-Fering OASL 1075 OASM : Samangan 1020 OAFR OAFR : Farah OASM 1081 OASN : Sheghnan 1019 OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad OASN 1077 OASP : Sare pul 1024 OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad OASP -

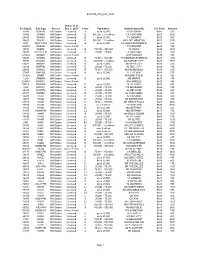

Freq Call State Location U D N C Distance Bearing

AM BAND RADIO STATIONS COMPILED FROM FCC CDBS DATABASE AS OF FEB 6, 2012 POWER FREQ CALL STATE LOCATION UDNCDISTANCE BEARING NOTES 540 WASG AL DAPHNE 2500 18 1107 103 540 KRXA CA CARMEL VALLEY 10000 500 848 278 540 KVIP CA REDDING 2500 14 923 295 540 WFLF FL PINE HILLS 50000 46000 1523 102 540 WDAK GA COLUMBUS 4000 37 1241 94 540 KWMT IA FORT DODGE 5000 170 790 51 540 KMLB LA MONROE 5000 1000 838 101 540 WGOP MD POCOMOKE CITY 500 243 1694 75 540 WXYG MN SAUK RAPIDS 250 250 922 39 540 WETC NC WENDELL-ZEBULON 4000 500 1554 81 540 KNMX NM LAS VEGAS 5000 19 67 109 540 WLIE NY ISLIP 2500 219 1812 69 540 WWCS PA CANONSBURG 5000 500 1446 70 540 WYNN SC FLORENCE 250 165 1497 86 540 WKFN TN CLARKSVILLE 4000 54 1056 81 540 KDFT TX FERRIS 1000 248 602 110 540 KYAH UT DELTA 1000 13 415 306 540 WGTH VA RICHLANDS 1000 97 1360 79 540 WAUK WI JACKSON 400 400 1090 56 550 KTZN AK ANCHORAGE 3099 5000 2565 326 550 KFYI AZ PHOENIX 5000 1000 366 243 550 KUZZ CA BAKERSFIELD 5000 5000 709 270 550 KLLV CO BREEN 1799 132 312 550 KRAI CO CRAIG 5000 500 327 348 550 WAYR FL ORANGE PARK 5000 64 1471 98 550 WDUN GA GAINESVILLE 10000 2500 1273 88 550 KMVI HI WAILUKU 5000 3181 265 550 KFRM KS SALINA 5000 109 531 60 550 KTRS MO ST. LOUIS 5000 5000 907 73 550 KBOW MT BUTTE 5000 1000 767 336 550 WIOZ NC PINEHURST 1000 259 1504 84 550 WAME NC STATESVILLE 500 52 1420 82 550 KFYR ND BISMARCK 5000 5000 812 19 550 WGR NY BUFFALO 5000 5000 1533 63 550 WKRC OH CINCINNATI 5000 1000 1214 73 550 KOAC OR CORVALLIS 5000 5000 1071 309 550 WPAB PR PONCE 5000 5000 2712 106 550 WBZS RI