9781474458894 Trumps Ameri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Reply Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Unseal by Raymond Bonner

Case 1:08-cv-01360-UNA Document 436 Filed 11/07/16 Page 1 of 32 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ZAYN AL ABIDIN MUHAMMAD ) HUSAYN (ISN # 10016), ) ) Petitioner. ) ) v. ) No. 08-CV-1360 ) ASHTON CARTER, ) ) Respondent. ) ) REPLY MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO UNSEAL BY RAYMOND BONNER David A. Schulz Hannah Bloch-Wehba Steven Lance (law student intern) Andrew Udelsman (law student intern) Media Freedom & Information Access Clinic Abrams Institute for Freedom of Expression Yale Law School P.O. Box 208215 New Haven, CT 06520 Phone: 212-850-6103 Fax: 212-850-6299 Chad Bowman Levine Sullivan Koch & Schulz, LLP 1899 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: 202-508-1100 Fax: 202-861-8988 Counsel for Movant Raymond Bonner Case 1:08-cv-01360-UNA Document 436 Filed 11/07/16 Page 2 of 32 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 2 I. JUDICIAL RECORDS ARE SUBJECT TO THE FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT OF ACCESS, EVEN WHEN THEY CONTAIN CLASSIFIED INFORMATION .......... 2 A. Classified Information Is Not Exempt From the Constitutional Access Right ....... 2 1. The government misapplies the “history and logic” test to the content of a record rather than the type of proceeding involved. ............... 2 2. The unilateral Executive authority to seal court records claimed by the government would violate the constitutional separation of powers. ..... 5 B. The Constitutional Standard Must Be Satisfied To Seal A Court Record That Contains Classified Information ..................................................................... 6 1. The Executive’s classification standards do not automatically satisfy the controlling First Amendment standard. -

Board Committee Academic Policy Documents B5 1

Board of Trustees of The City University of New York RESOLUTION I.B.5 TO Award an Honorary Degree at Commencement by the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism October 7, 2019 WHEREAS, journalist Masha Gessen is one of the keenest investigative reporters and observers of Russian politics and culture, as well as the present world of political life in the United States; and WHEREAS, Gessen, a staff writer at the New Yorker, is the author of ten books and countless articles for a variety of top journalistic outlets, including Slate, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, U.S. News & World Report, and The New Republic; and WHEREAS, their publications have been acknowledged with numerous awards, fellowships and other honors, including the 2017 National Book Award for The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia; and WHEREAS, the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism is committed to serving the public interest by cultivating the next generation of skilled, ethically minded, and diverse journalists, and Gessen represents the values to which the Newmark J-School holds true, and to which we hope our graduates aspire; and WHEREAS, in granting this degree, the Newmark J-School will recognize Gessen's extensive contributions to our understanding of Russia and the importance of free expression through insightful and provocative books, essays, and articles; and WHEREAS, the honorary degree will also recognize their commitment to a robust democratic life, an informed electorate, and an active fourth estate; and WHEREAS, with the Newmark's J-School's emphasis on investigative reporting and the importance of strong journalism that stands up to tyranny, Gessen is an ideal candidate for the first-ever honorary CUNY degree from the J-School NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, That the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY award Masha Gessen the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa, at the school’s commencement ceremony on December 13, 2019. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

March 18, 2014

March 18, 2014 Student Highlight Faculty Updates Mazal Collection in the News Russian-A merican Journalist & A ctivist Masha Gessen Comes to CU East European Jewish A ffairs Journal Embodied Judaism Symposium Online Resources and Scholarships for Students On Campus & A round Town Student Highlight... Chelsea is pursuing a minor in Jewish Studies in addition to a major in International Affairs and a certificate in Digital Arts and Media. She first joined the Program in Jewish Studies because she wanted to incorporate genocide and religious studies into her broader major, and was specifically attracted to learning about gendered experiences within both the Holocaust and Judaism. We would like to congratulate Chelsea on recently being awarded the 2014 Jacob Van Ek S cholar Award! An outstanding student, this past year, Chelsea has also received the Wrenn Scholarship from the Boulder Chapter of the United Nations Association and the Ripple Award from the Dennis Small Cultural Center. During her time at CU, Chelsea has served as a member of the Jewish Studies Student Advisory Board, was the co-president of Hillel, played for CU's Women's Rugby team, served on CUSG and Student Outreach Retention Center for Equity (SORCE), and was on the KVCU Radio 1190 Task Force. Chelsea also works for the CU Recreation Center. This past summer 2013, Chelsea completed the CU in D.C. summer session, interning with Women's Action for New Directions and the Women Legislators' Lobby in Washington, DC. She worked particularly on women's advocacy and defense budget issues, as well as nuclear policies. -

The Public Eye, Fall 2002

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL PublicEyeRESEARCH ASSOCIATES FALL 2002 • Volume XVI, No. 3 The Right Family Values The Christian Right’s “Defense of Marriage:” unpopular beliefs. Despite the First Amendment’s prohi- Democratic Rhetoric, Antidemocratic Politics bition against the establishment of religion by government, Christian conservatives By R. Claire Snyder cans oppose. While conservative Americans and their supporters often insist that Amer- are free to practice their beliefs and live their ica is really a “Christian nation.” They Introduction1 personal lives however they choose, the argue that the American founders believed government of the United States cannot he United States was founded as a that democratic political institutions would legitimately let those beliefs violate the “liberal democracy,” in which a secu- only work if grounded in religious mores T human rights of others in society. Similarly, lar government acts to protect the civil within civil society, emphasizing a comment it cannot generate public policy supporting rights and liberties of individuals rather made by John Adams: “Our Constitution a particular religious worldview or deny legal than imposing a particular vision of the was made only for a moral and religious peo- equality to certain groups of citizens. “good life” on its citizens. Equality before ple. It is wholly inadequate to the govern- the law constitutes one of the most funda- ment of any other.”9 William Bennett has mental principles of liberal democracy, as Liberal Democracy or Christian Nation? contributed greatly to this right-wing proj- does freedom from State-imposed religion. ect of revisionist historiography with the iberal political theory constitutes the These principles, enshrined in our found- publication of Our Sacred Honor: Words of ing documents, have become an almost Lmost important founding tradition of 5 Advice from the Founders, a volume that cat- universally accepted norm in U.S. -

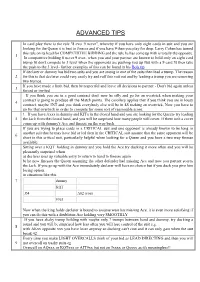

Advanced Tips

ADVANCED TIPS In card play there is the rule "8 ever 9 never", whereby if you have only eight cards in suit and you are looking for the Queen it is best to finesse and if you have 9 then you play for drop. Larry Cohen has turned this rule on its head for COMPETITIVE BIDDING and the rule he has come up with is totally the opposite. 1 In competitive bidding 8 never 9 ever- when you and your partner are known to hold only an eight card trump fit don't compete to 3 level when the opponents are pushing you up But with a 9 card fit then take the push to the 3 level- further examples of this can be found in his Bols tip If declarer or dummy has bid two suits and you are strong in one of the suits then lead a trump. The reason 2 for this is that declarer could very easily try and ruff this suit out and by leading a trump you are removing two trumps. If you have made a limit bid, then be respectful and leave all decisions to partner - Don't bid again unless 3 forced or invited If you think you are in a good contract don't now be silly and go for an overtrick when making your contract is going to produce all the Match points. The corollary applies that if you think you are in lousy 4 contract, maybe 3NT and you think everybody else will be in 4S making an overtrick, Now you have to go for that overtrick in order to compete for some sort of reasonable score. -

The Great White Hoax

THE GREAT WHITE HOAX Featuring Tim Wise [Transcript] INTRODUCTION Text on screen Charlottesville, Virginia August 11, 2017 Protesters [chanting] You will not replace us! News reporter A major American college campus transformed into a battlefield. Hundreds of white nationalists storming the University of Virginia. Protesters [chanting] Whose streets? Our streets! News reporter White nationalists protesting the removal of a Confederate statue. The setting a powder keg ready to blow. Protesters [chanting] White lives matter! Counter-protesters [chanting] Black lives matter! Protesters [chanting] White lives matter! News reporter The march spiraling out of control. So-called Alt-Right demonstrators clashing with counter- protesters some swinging torches. Text on screen August 12, 2017 News reporter (continued) The overnight violence spilling into this morning when march-goers and counter-protesters clash again. © 2017 Media Education Foundation | mediaed.org 1 David Duke This represents a turning point for the people of this country. We are determined to take our country back. We're going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump. That's what we believed in. That's why we voted for Donald Trump. Because he said he's going to take our country back. And that's what we gotta do. News reporter A horrifying scene in Charlottesville, as this car plowed into a crowd of people. The driver then backing up and, witnesses say, dragging at least one person. Donald Trump We're closely following the terrible events unfolding in Charlottesville, Virginia. We condemn, in the strongest possible terms, this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides. On many sides. -

The Evil Savage Other As Enemy in Modern U.S. Presidential Discourse

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The Evil Savage Other as Enemy in Modern U.S. Presidential Discourse Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/498 DOI: 10.4000/angles.498 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, « The Evil Savage Other as Enemy in Modern U.S. Presidential Discourse », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/498 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.498 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The Evil Savage Other as Enemy in Modern U.S. Presidential Discourse 1 The Evil Savage Other as Enemy in Modern U.S. Presidential Discourse Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy 1 Most scholars in international relations hold the view that our knowledge of the world is a human and social construction rather than the mere reflection of reality (Wendt 1994; Finnemore 1996). This perspective, rooted in constructivist epistemology, implies that nations are not unquestionable ancient natural quasi-objective entities, as primordialist nationalists claim, but rather cognitive constructions shaped by stories their members imagine and relate.1 This was famously illustrated by Benedict Anderson’s study of nationalism that reached the compelling conclusion that any community “larger than that primordial village of face-to-face contact” can only be imagined (Anderson 1983: 6). The identity of a nation is undoubtedly dependent on stories its members imagine and relate. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

C:\My Documents\Adobe\Boston Fall99

Presents They Had Their Beans Baked In Beantown Appeals at the 1999 Fall NABC Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................... iii The Expert Panel.................................................v Cases from San Antonio Tempo (Cases 1-24)...........................................1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 25-35)..........................93 Misinformation (Cases 35-49) .................................125 Claims (Cases 50-52)........................................177 Other (Case 53-56)..........................................187 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists..........................199 Closing Remarks From the Editor..................................203 Special Section: The WBF Code of Practice (for Appeals Committees) ....209 The Panel’s Director and Committee Ratings .........................215 NABC Appeals Committee .......................................216 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMPP Appeal Without Merit Penalty Point LA Logical Alternative MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue with our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always, our goal is to provide information and to foster change for the better in a manner that is entertaining, instructive and stimulating. The ACBL Board of Directors is testing a new appeals process at NABCs in 1999 and 2000 in which a Committee (called a Panel) comprised of pre-selected top Directors will hear appeals at NABCs from non-NABC+ events (including side games, regional events and restricted NABC events). Appeals from NABC+ events will continue to be heard by the National Appeals Committees (NAC). We will review both types of cases as we always have traditional Committee cases. Panelists were sent all cases and invited to comment on and rate each Director ruling and Panel/Committee decision. Not every panelist will comment on every case. -

The Case of Donald J. Trump†

THE AGE OF THE WINNING EXECUTIVE: THE CASE OF DONALD J. TRUMP† Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash∗ INTRODUCTION The election of Donald J. Trump, although foretold by Matt Groening’s The Simpsons,1 was a surprise to many.2 But the shock, disbelief, and horror were especially acute for the intelligentsia. They were told, guaranteed really, that there was no way for Trump to win. Yet he prevailed, pulling off what poker aficionados might call a back- door draw in the Electoral College. Since his victory, the reverberations, commotions, and uproars have never ended. Some of these were Trump’s own doing and some were hyped-up controversies. We have endured so many bombshells and pur- ported bombshells that most of us are numb. As one crisis or scandal sputters to a pathetic end, the next has already commenced. There has been too much fear, rage, fire, and fury, rendering it impossible for many to make sense of it all. Some Americans sensibly tuned out, missing the breathless nightly reports of how the latest scandal would doom Trump or why his tormentors would soon get their comeuppance. Nonetheless, our reality TV President is ratings gold for our political talk shows. In his Foreword, Professor Michael Klarman, one of America’s fore- most legal historians, speaks of a degrading democracy.3 Many difficulties plague our nation: racial and class divisions, a spiraling debt, runaway entitlements, forever wars, and, of course, the coronavirus. Like many others, I do not regard our democracy as especially debased.4 Or put an- other way, we have long had less than a thoroughgoing democracy, in part ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– † Responding to Michael J.