Fiscal Focus: Brownfield Redevelopment Financing: Tax Increment Legislation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

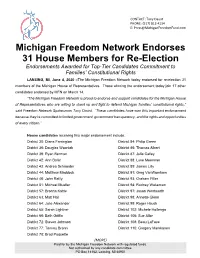

Michigan Freedom Network Endorses 31 House Members for Re-Election Endorsements Awarded for Top-Tier Candidates Commitment to Families’ Constitutional Rights

CONTACT: Tony Daunt PHONE: (517) 812-4134 E: [email protected] Michigan Freedom Network Endorses 31 House Members for Re-Election Endorsements Awarded for Top-Tier Candidates Commitment to Families’ Constitutional Rights LANSING, MI, June 4, 2020 –The Michigan Freedom Network today endorsed for re-election 31 members of the Michigan House of Representatives. Those winning the endorsement today join 17 other candidates endorsed by MFN on March 14. “The Michigan Freedom Network is proud to endorse and support candidates for the Michigan House of Representatives who are willing to stand up and fight to defend Michigan families’ constitutional rights,” said Freedom Network Spokesman Tony Daunt. “These candidates have won this important endorsement because they’re committed to limited government, government transparency, and the rights and opportunities of every citizen.” House candidates receiving this major endorsement include: District 30: Diana Farrington District 84: Philip Green District 36: Douglas Wozniak District 86: Thomas Albert District 39: Ryan Berman District 87: Julie Calley District 42: Ann Bollin District 88: Luke Meerman District 43: Andrea Schroeder District 89: James Lilly District 44: Matthew Maddock District 91: Greg VanWoerkom District 46: John Reilly District 93: Graham Filler District 51: Michael Mueller District 94: Rodney Wakeman District 57: Bronna Kahle District 97: Jason Wentworth District 63: Matt Hall District 98: Annette Glenn District 64: Julie Alexander District 99: Roger Hauck District 65: Sarah Lightner District 102: Michele Hoitenga District 66: Beth Griffin District 106: Sue Allor District 72: Steven Johnson District 108: Beau LaFave District 77: Tommy Brann District 110: Gregory Markkanen District 78: Brad Paquette (MORE) Paid for by the Michigan Freedom Network with regulated funds. -

July 27, 2018 Senate Campaign Finance Reports

District Party Candidate Jan. 1-July 22 Raised Total Raised Jan. 1-July 22 Spent Total Spent Debts Cash On Hand Top Contributor 2nd Contributor 3rd Contributor 1 R Pauline Montie WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 1 D James Cole Jr. WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 1 D Nicholas Rivera WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 1 D Stephanie Chang $72,488 $147,043 $105,398 $107,008 $0 $40,035 Carpenters ($6,500) Henry Ford Health System ($2,250) Michigan Education Assoc. ($1,750) 1 D Alberta Tinsley Talabi $9,865 $9,865 $4,766 $4,766 $5,258 $5,099 Alberta Tinsley Talabi ($5,258) NICHOLSON ($2,000) Larry Brinker ($1,000) 1 D Stephanie Roehm 1 D Bettie Cook Scott 2 R John Hauler WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D Tommy Campbell WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D Lawrence E. Gannan WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D LaMar Lemmons WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D William Phillips WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D Joe Ricci WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER WAIVER 2 D Adam Hollier $120,988 $120,988 $104,214 $104,215 $12,480 $25,850 Adam J. Hollier ($16,480.47) DUGGAN LEADERSHIP FUND ($15,000) David Fink ($2,000) 2 D Brian Banks $114,050 $156,875 $98,984 $106,522 $25,000 $50,353 Brian Banks ($33,500) MICHIGAN ASSOCIATION FOR JUSTICE PAC ($11,500)OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCAL 324 ($10,000) 2 D Abraham Aiyash $104,596 $104,596 $13,347 $13,347 $0 $91,249 WADHA AIYASH ($2,000) HAFAID GOBAH ($2,000) NASHWAN QURAY ($2,000) 2 D George Cushingberry Jr. -

Good Government Fund Contributions to Candidates and Political Committees January 1 ‐ December 31, 2018

GOOD GOVERNMENT FUND CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018 STATE RECIPIENT OF GGF FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE CA Jeff Denham, Jeff PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC DC Association of American Railroads PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Trade Assn PAC FL Bill Nelson, Moving America Forward PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA David Perdue, One Georgia PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA Johnny Isakson, 21st Century Majority Fund Fed $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC MO Roy Blunt, ROYB Fund $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC NE Deb Fischer, Nebraska Sandhills PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC OR Peter Defazio, Progressive Americans for Democracy $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SC Jim Clyburn, BRIDGE PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SD John Thune, Heartland Values PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC US Dem Cong Camp Cmte (DCCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Cong Cmte (NRCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Dem Sen Camp Cmte (DSCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Sen Cmte (NRSC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct VA Mark Warner, Forward Together PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC VA Tim Kaine, Common -

CAPITOL NEWS UPDATE January 27, 2017

MCALVEY MERCHANT & ASSOCIATES CAPITOL NEWS UPDATE January 27, 2017 CAPITOL NEWS UPDATE WEEK OF JANUARY 23, 2017 Integrity, Individual Attention. Precision Strategy. Proven Results SCHOOL REFORM OFFICE RELEASES LIST OF POOR-PERFORMING PUBLIC SCHOOLS SET TO CLOSE On Jan. 20. the state School Reform Office released a list of 38 schools facing closure by the end of the school year due to poor academic performance. The list includes 24 schools in the Detroit Public Schools Community District and the state-created Education Achievement Authority in the city of Detroit. The SRO had discussed the potential closures months ago, warning schools that they could be shut down if they showed no academic improvement and continued poor performance from 2014 to 2016. The action could impact more than 18,000 students. The SRO is in the process of sending out closure notices, and has already sent letters to parents of children who attend classes in the 38 schools. It is also in the process of examining which other public schools the children would attend if their school closes. If a school closing creates an unreasonable hardship on the students, or all the other surrounding public schools also on the list, the SRO will pursue other options. Senate Education Committee Chair Phil Pavlov (R-St. Clair) is looking into repealing the state’s “failing schools” law and creating one system to explain how schools are placed on the list. The SRO also announced 79 schools were being released from the state’s Priority School list. HOUSE ANNOUNCES COMMITTEE ASSIGNMENTS FOR 2017-18 House Republicans announced their 2017-2018 committee assignments, including 11 freshman with chairmanship. -

Member Roster

Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Legislative Caucus MEMBER ROSTER December 2020 Indiana Senator Ed Charbonneau, Chair Illinois Representative Robyn Gabel, Vice Chair Illinois Indiana (con’t) Michigan (con’t) Senator Omar Aquino Representative Carey Hamilton Representative Jim Lilly Senator Melinda Bush Representative Earl Harris, Jr. Representative Leslie Love Senator Bill Cunningham Representative Matt Pierce Representative Steve Marino Senator Laura Fine* Representative Mike Speedy Representative Gregory Markkanen Senator Linda Holmes Representative Denny Zent Representative Bradley Slagh Sentator Robert Martwick Representative Tim Sneller Senator Julie A. Morrison Michigan Representative William Sowerby Senator Elgie R. Sims, Jr. Senator Jim Ananich Representative Lori Stone Representative Kelly Burke Senator Rosemary Bayer Representative Joseph Tate Representative Tim Butler Senator John Bizon Representative Rebekah Warren Representative Jonathan Carroll Senator Winnie Brinks Representative Mary Whiteford Representative Kelly M. Cassidy Senator Stephanie Chang Representative Robert Wittenberg Representative Deborah Conroy Senator Erika Geiss Representative Terra Costa Howard Senator Curtis Hertel, Jr. Minnesota Representative Robyn Gabel* Senator Ken Horn Senator Jim Abeler Representative Jennifer Gong- Senator Jeff Irwin Senator Thomas M. Bakk Gershowitz Senator Dan Lauwers Senator Karla Bigham Representative Sonya Marie Harper Senator Jim Runestad Senator Steve Cwodzinski Representative Elizabeth Hernandez Senator Wayne A. Schmidt Senator -

Issue No. 13 – 2020 (Published August 1, 2020)

Michigan Register Issue No. 13 – 2020 (Published August 1, 2020) GRAPHIC IMAGES IN THE MICHIGAN REGISTER COVER DRAWING Michigan State Capitol: This image, with flags flying to indicate that both chambers of the legislature are in session, may have originated as an etching based on a drawing or a photograph. The artist is unknown. The drawing predates the placement of the statue of Austin T. Blair on the capitol grounds in 1898. (Michigan State Archives) PAGE GRAPHICS Capitol Dome: The architectural rendering of the Michigan State Capitol’s dome is the work of Elijah E. Myers, the building’s renowned architect. Myers inked the rendering on linen in late 1871 or early 1872. Myers’ fine draftsmanship, the hallmark of his work, is clearly evident. Because of their size, few architectural renderings of the 19th century have survived. Michigan is fortunate that many of Myers’ designs for the Capitol were found in the building’s attic in the 1950’s. As part of the state’s 1987 sesquicentennial celebration, they were conserved and deposited in the Michigan State Archives. (Michigan State Archives) East Elevation of the Michigan State Capitol: When Myers’ drawings were discovered in the 1950’s, this view of the Capitol – the one most familiar to Michigan citizens – was missing. During the building’s recent restoration (1989-1992), this drawing was commissioned to recreate the architect’s original rendering of the east (front) elevation. (Michigan Capitol Committee) Michigan Register Published pursuant to § 24.208 of The Michigan Compiled Laws Issue No. 13— 2020 (This issue, published August 1, 2020, contains documents filed from July 1, 2020 to July 15, 2020) Compiled and Published by the Michigan Office of Administrative Hearings and Rules © 2020 by Michigan Office of Administrative Hearings and Rules, State of Michigan All rights reserved. -

Michigan Commission of Agriculture and Rural Development Meeting Minutes January 20, 2021 Drafted January 25, 2021 Page 1

STATE OF MICHIGAN GRETCHEN WHITMER DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE GARY MCDOWELL GO VERNOR AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR February 24, 2021 NOTICE OF MEETING MICHIGAN COMMISSION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT March 10, 2021 The regular meeting of the Michigan Commission of Agriculture and Rural Development will be held on March 10, 2021. The business session is scheduled to begin at 9:00 a.m. The meeting is open to the public and this notice is provided under the Open Meetings Act, 1976 PA 267, MCL 15.261 to 15.275. This meeting is being conducted electronically to protect the health of commission members, staff, and the public due to the Coronavirus by limiting the number of people at public gatherings. To join the meeting, dial by telephone: 1-248-509-0316 and enter Conference ID: 273 662 491#. In accordance with the Commission’s Public Appearance Guidelines, individuals wishing to address the Commission may pre-register to do so during the Public Comment period as noted below and will be allowed up to three minutes for their presentation. Documents distributed in conjunction with the meeting will be considered public documents and are subject to provisions of the Freedom of Information Act. The public comment time provides the public an opportunity to speak; the Commission will not necessarily respond to the public comment. To pre-register to speak during this remote meeting, individuals should contact the Commission Assistant no later than Fri., October 30, via email at [email protected] and provide their name, organization they represent, address, and telephone number, as well as indicate if they wish to speak to an agenda item. -

Michigan Senate Photo Directory for 2021-2022

Michigan Senate Photo Directory For 2021-2022 Senate Leadership Majority Leader President Majority Floor President Pro Leader Tempore Mike Shirkey Garlin Gilchrist II Dan Lauwers Aric Nesbitt R-Clarklake D-Detroit R-Brockway R-Lawton Associate Assistant Majority Majority Caucus Majority Caucus President Pro Leader Chair Whip Tempore Marshall Bulloc k Wayne Schmid t Curt VanderWal l John Bizon D-Detroit R-Traverse City R-Ludington R-Battle Creek Minority Leader Minority Floor Leader Jim Ananich Stephanie Chan g D-Flint D-Detroit Full Senate Membership: District 5 District 27 District 24 District 12 Betty Alexande r Jim Ananich Tom Barrett Rosemary Baye r D-Detroit D-Flint R-Charlotte D-Beverly Hills 1st Term 2nd Term 1st Term 1st Term District 19 District 29 District 4 District 34 John Bizon Winnie Brinks Marshall Bulloc k Jon Bumstead R-Battle Creek D-Grand Rapids D-Detroit R-Newaygo 1st Term 1st Term 1st Term 1st Term District 1 District 31 District 6 District 23 Stephanie Chan g Kevin Daley Erika Geiss Curtis Hertel Jr . D-Detroit R-Lum D-Taylor D-East Lansing 1st Term 1st Term 1st Term 2nd Term District 2 District 32 District 18 District 14 Adam Hollier Ken Horn Jeff Irwin Ruth Johnson D-Detroit R-Frankenmut h D-Ann Arbor R-Holly 1st Term 2nd Term 1st Term 1st Term District 21 District 25 District 10 District 38 Kim LaSata Dan Lauwers Michael Ed McBroom R-Bainbridge Township R-Brockway MacDonald R-Vulcan 1st Term 1st Term R-Macomb Township 1st Term 1st Term District 20 District 13 District 11 District 26 Sean McCann Mallory McMorrow -

The Senate P.O

MEMBERS: S-106 CAPITOL BUILDING THE SENATE P.O. BOX 30036 SEN. DAN LAUWERS, MAJORITY VICE CHAIR LANSING, MICHIGAN 48909-7536 SEN. ARIC NESBITT COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT PHONE: (517) 373-5932 SEN. JIM ANANICH, MINORITY VICE CHAIR OP ERATIONS SEN. STEPHANIE CHANG FAX: (517) 373-5944 SENATOR MIKE SHIRKEY CHAIR ** DRAFT ** COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES December 10, 2019 A meeting of the Senate Committee on Government Operations was scheduled for Tuesday, December 10, 2019, at 2:00 p.m., in rooms 402 & 403 of the Capitol Building. _______________________________________________________________________________________ The agenda summary is as follows: 1. Reported HB 4095 (Rep. Reilly) with recommendation and immediate effect. _______________________________________________________________________________________ At 2:00 p.m., the Chairman called the meeting to order He instructed the Clerk to call the roll. At that time, the following members were present; Chairman Shirkey, Sen.(s) Lauwers, Nesbitt, Ananich and Chang a quorum was present. The Chairman entertained a motion by Sen. Nesbitt to adopt the committee meeting minutes from November 12, 2019. Without Objection, the minutes were adopted. The Chairman invited Adam deAngeli, of Rep. Reilly's office, to summarize HB 4095. The Chairman invited the following individuals to present testimony regarding HB 4095: Sen. Johnson, 14th Senate District – Oppose Sen. Bayer, 12th Senate District – Oppose Jason & Maggie Dunn, House of Providence, Support Dr. Nicole Lawson, Oakland Community Health Network – Oppose Annette Downey, Community Living Services – Oppose Due to time constraints the following individuals were unable to testify regarding HB 4095: Kadi Prout, Michigan Federation for Children and Families – Support Scott Kempa, Rep. Mike Mueller – Oppose Jillian Trumbull, Oakland CHN – Oppose Robert DePalma, Groveland Twp. -

2018 Michigan State Senate Race September 2017

2018 Michigan State Senate Race September 2017 This is a preliminary report on the 2018 Michigan State Senate races. It includes filed and prospective candidates from each of the 38 Senate districts along with district maps and current Senators. The information in this document is taken from multiple sources. Updates will be made as Senate races progress. If you have any questions or comments please contact us at Public Affairs Associates. 1 1st District Current Senator: Coleman A. Young, Jr. (D-Detroit), (term-limited) Filed: Rep. Stephanie Chang (D-Detroit) Nicholas Rivera (D), Admissions Counselor at Wayne State University Prospective: Rep. Bettie Cook Scott (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Alberta Tinsley-Talabi (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Detroit). Rep. Tlaib’s run is a possibility, but with Chang in the race it’s questionable. Rico Razo, Mayor Mike Duggan’s re-election campaign manager Denis Boismier, Gibraltar City Council President. Although Boismier is running for Gibraltar mayor this year, he may possibly join the race if the field becomes heavily saturated with Detroit candidates. 2 2nd District Current Senator: Bert Johnson (D-Highland Park), (term-limited) Filed: Tommy Campbell (D-Grosse Pointe) Rep. Brian Banks (D-Harper Woods) Adam Hollier, former aide to Sen. Johnson Prospective: Former Rep. Lamar Lemmons (D-Detroit) Former Rep. John Olumba (D-Detroit) 3 3rd District Current Senator: Morris Hood III (D-Detroit), (term-limited) Filed: N/A Prospective: Rep. Sylvia Santana (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Harvey Santana (D-Detroit) Former Rep. David Nathan (D-Detroit) Former Rep. Gary Woronchak (R-Dearborn), current Wayne County Commission Chair 4 4th District Current Senator: Ian Conyers (D-Detroit), (Incumbent) Filed: N/A Prospective: N/A 5 5th District Current Senator: David Knezek (D-Dearborn Heights), (Incumbent) Filed: DeShawn Wilkins (R-Detroit) Prospective: N/A 6 6th District Current Senator: Hoon-Yung Hopgood (D-Taylor), (term-limited) Filed: Rep. -

Member Roster

MEMBER ROSTER April 2021 Illinois Representative Robyn Gabel, Chair Representative Jennifer Schultz, Vice Chair Illinois Michigan (con’t) Minnesota (con’t) Senator Omar Aquino Senator Curtis Hertel, Jr. Senator Mary Kunesh Senator Bill Cunningham Senator Ken Horn Senator Jen McEwen Senator Laura Fine Senator Jeff Irwin Senator Jerry Newton Senator Ann Gillespie Senator Dan Lauwers Senator Ann H. Rest* Senator Linda Holmes Senator Jim Runestad Senator Carrie L. Ruud* Senator Elgie R. Sims, Jr. Senator Wayne A. Schmidt Senator David H. Senjem Representative Tim Butler Senator Curt VanderWall Senator David J. Tomassoni Representative Jonathan Carroll Senator Roger Victory Representative Patty Acomb Representative Terra Costa Howard Senator Paul Wojno Representative Heather Edelson Representative Robyn Gabel* Representative Joseph Bellino Representative Rick Hansen Representative Jennifer Gong- Representative Tommy Brann Representative Jerry Hertaus Gershowitz Representative Julie Brixie Representative Frank Hornstein Representative Sonya Marie Harper* Representative Sara Cambensy Representative Sydney Jordan Representative Rita Mayfield Representative Phil Green Representative Fue Lee Representative Anna Moeller Representative Kevin Hertel Representative Todd Lippert Representative Bob Morgan Representative Rachel Hood Representative Jeremy Munson Representative David Welter Representative Gary Howell Representative Liz Olson Representative Bronna Kahle Representative Duane Quam Indiana Representative Beau LaFave Representative Jennifer -

2019-2020 Legislative Scorecard Summary

2019-2020 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD SUMMARY WHAT MADE THIS POSSIBLE? YOU! TOWARD A CONSERVATION MAJORITY In 2019 and 2020, you used your voice to tell your Because Michigan LCV is both political and non- legislators to move forward with clean energy, partisan, our goal is to build a pro-conservation demand clean drinking water in our communities majority of state lawmakers from both parties who and conserve our state’s incredible natural support protecting the health of our communities resources. by tackling the big issues facing Michigan’s land, air, and water. Together, we are making a difference. An important part of our work is holding our elected officials accountable. This scorecard tells HOUSE you whether your representatives in Lansing Conservation Majority Breakdown listened to you and your neighbors, or if they listened to special interests. YES = 50 TELL YOUR LEGISLATORS MAYBE = 31 YOU KNOW THE SCORE NO = 31 1 It only takes a minute to say thanks-- or to TOTAL = 112 say no thanks-- to your legislators. DONATE Because we could not accomplish our 2 mission without the generous support of SENATE our members, please make a donation so Conservation Majority Breakdown we can continue fighting for clean air and clean water in your community and continue YES = 16 our stewardship of Michigan’s unparalleled natural resources. MAYBE = 3 NO = 19 SPREAD THE WORD Finally, share this scorecard with your TOTAL = 38 3 friends and family so they know the score of their elected officials, too. Total number of legislators in the Michigan House exceeds number YOU CAN DO ALL OF THIS AT of House districts due to an early resignation and the passing of one MICHIGANLCV.ORG/SCORECARD Representative during the term.