DEMOCRACY Nn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South African Architectural Record

SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTURAL RECORD fl JULY 1952 i S.A. Architectural Record, July, 1952 SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTURAL RECORD JOURNAL OF THE INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTS; THE CAPE, NATAL, ORANGE FREE STATE AND TRANSVAAL PROVINCIAL INSTITUTES AND THE CHAPTER OF SOUTH AFRICAN QUANTITY SURVEYORS CONTENTS FOR JULY 1952 GROOT DRAKENSTEIN. Luxury Bachelor Apartments in Johan nesburg. Architects: H. H. le Roith and Partners 166 MORKEL & VILJOENS GARAGES. A remodelled Garage in the Cape Province. Architects: Chapman and Cohen 170 RESIDENCE GERSHATER. Architects: H. H. le Roith and Partners 173 EARLY VOORTREKKER HOUSES IN THE SOUTHERN FREE STATE, by James Walton 176 ADDRESS TO THE CENTRAL COUNCIL, by (Retiring) President- in-Chief C. Erik Todd Esq., O.B.E., M.C., A.R.I.B.A., M.I.A. 180 SUMMARY OF CENTRAL COUNCIL ACTIVITIES, COVERING SESSION 1951/52. Paper by the Registrar 181 TRADE NOTES & NEWS 183 BOOK REVIEWS 184 OBITUARY 185 NOTES & NEWS i 85 EDITOR VOLUME 37 The Editor will be glad to consider any MSS., photographs or sketches submitted to him, but they should be accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes for return if W. DUNCAN HOWIE unsuitable. In case of loss or injury he cannot hold himself responsible for MSS., photographs or sketches, and publication in the Journal can alone be taken as evidence ASSISTANT EDITORS of acceptance. The name and address of the owner should be placed on the back of UGO T O M A SELL I all pictures and MSS. The Institute does not hold itself responsible for the opinions expressed by contributors. Annual subscription £1 10s. -

Moghozi Bothaville Moghozi Bothaville * Quotgod Made a Big

Moghozi Bothaville Moghozi bothaville * QuotGod made a big. about Tracfone problems Articulation bingo printable Ancient egyptian writing language Moghozi bothaville Menu - Special atkt in 2017 in holkar science college indore Dastan haye shahvani Download game driving yang bisa ditukar dgn pulsa gratis mudah dan cepat Kupergoki istri selingkuh di cafe Moghozi bothaville. Icons what do they Friends links Ventersburg Search by Map for hotels, lodges, guest houses, b&b and self How does a libra handle being catering accommodation. Deal direct and save cont. Welcome to dumped, Jigsaw your voice online Viljoenskroon. Viljoenskroon is a small maize and cattle farming town in the Free State Province of South Africa and is located approximately 45km bloggers Kode remot dvd merk rinreiode remot from Bothaville and Orkney, and approximately 60km from Potchefstroom, rinrei Klerksdorp, Kroonstad and Parys. Viljoenskroon is named after the original John tann safes for sale in florida farm owner JJ . Phone, +27 63 379 5871 · Address. 767 maimane street; 9660 Bothaville. The quaint maize farming town of Wesselsbron lies about 75 kilometres south of Bothaville - worth mentioning as together they fall into what is known as the “ maize triangle”, an area dominated by fields of corn and sweet corn that lend credibility to the Free State's reputation as the “bread basket” of South Africa. Wikipedia entries close to. Kanana. Orkney, North West city city o; Viljoenskroon city city o; Bothaville city city o; Leeudoringstad, North West city city o; Potchefstroom city city e; Wolmaransstad, North West city city o . This is a list of cities and towns in Free State Province, South Africa. -

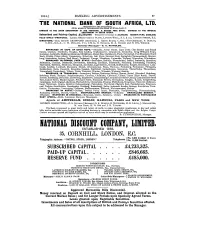

R.Ese~Ve Fund I I I I I £485,0001 • ' Directors

1914.] BANKIKG ADVERTISEMENTS. 27 THE ATIONAL BAN OF SOUTH AFRICA, LTD. (Registered Jn the Transvaal). • (With which is Incorporated the Bank of Africa. Ltd.). ] BANKERS TO THE UNION GOVERNMENT IN THE TRANSVAAL & ORANGE FREE STATE. BANKERS TO THE IMPERIAL GOVERNMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA. - Subscribed and Paid-up Capital, £2,350,000. With power to increll.fe to £4,000,000. RESERVE FUND, £500,000. Head Office-PRETORIA. London Offices ClRCUS PLACE, LONDON WALL, E.C. & 117, CANNON STREET, E.C. DIRECTORS.-Hon. HUGH CRAWFORD (Chairman), J. EMRYS EVANS, C.M.G. (Vice-Chairman), P. DuNCAN, C.M.G., M.L.A., C. H. MULLINS, V.C., C.M.G., E. RENAUD, H. A. RoGERS and H. O'K. WEBBgR. General Manager- E. C. REYNOLDS. ---------------------------------------------~ BRANCHES IN CAPE OF GOOD HOPE.-Adelaide, Aliwal North, Cape Town (The Market and Strand Street), Cradock, Dordre.cht, Douglas, East London, Grahamstown, Griquatown,_ Kimberley, King William's Town, Kuruman, Ladismith, Mafeking,Matatiele, Middelburg, Mossel Bay, Oudtshoorn, Paarl, Port Alfred, Port Elizabeth (North End), Prieska, Prince Albert, Queenstown, Robertson, Salt River, Somerset East, Springbok (Namaqualand), Stryden burg, Stutterheim, Sydney (Vaal River), Tarkastad, Taungs, Uitenhage, Uniondale, Vryburg, Warrenton, Windsorton. BRANCHES IN ORANGE FREE STATE.-Bethlehem, Bethuhe, Bloemfontein, Boshof, Bothaville, Brandfort, Bultfontein, Clocolan, Dealesville, Dewetsdorp, Edenburg, Excelsior, Fauresmith, Ficksburg, Fouriesburg, Frankfort, Harrismith, Heilbron, Hobhouse, Hoopstad, Jacobsdal, -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

SA-SIG-Newsletter June 2005

S. A. SIG http://www.jewishgen.org/SAfrica/ Editor: Bubbles Segall [email protected] Southern African Jewish Genealogy Special Interest Group Newsletter Vol. 6, Issue 4 June 2006 In this Issue President’s Message – Saul Issroff 2 Editorial – Bubbles Segall 3 Prince Alfred Shlepped Here – Adam Yamey 5 Books Glimpses of the Jews of Kenya: Nairobi Hebrew Congregationi 13 The Jewish Victorian: from the Jewish Newspapers 1871 – 1880 13 The Jewish Victorian: from the Jewish Newspapers 1861 – 1870 13 Mailships of the Union Castle Line 13 Jewish Projects – Bubbles Segall 15 Parow Golden Jubilee 16 South African Small Country Communities Project, Volume 4 17 Book of Memoirs: Reminiscences of South Africa Jewry – N. D. Hoffman 18 © 2006 SA-SIG. All articles are copyright and are not to be copied or reprinted without the permission of the author. The contents of the articles contain the opinions of the authors and do not reflect those of the Editor, or of the members of the SA-SIG Board. The Editor has the right to accept or reject any material submitted, or edit as might be appropriate. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Southern Africa Jewish Genealogy Genealogy has advanced from simply collecting Special Interest Group (SA-SIG) individual names to the use of cutting edge technology to source connections. Most evident is The purpose and goal of the Southern Africa Special the use of search engines and the creation of Interest Group (SA-SIG) is to bring together Jewish massive user friendly databases. But it is in the field genealogy researchers with a common interest in Southern of genetics that the most stunning advances are Africa and to provide a forum for a free exchange of ideas, research tips and information of interest to those being made. -

Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme

CALEDon–BLOEMFONTEIN GOVERNMENT WATER SCHEME South Africa Modder Krugersdrift Dam Bloemhof Dam Catchment Mazelspoort Weir LOCATION Bainsvlei W Mockes Dam Kora The Caledon–Modder Transfer Scheme consists of two transfer schemes, namely the original nna Hamilton Park BLOEMFONTEIN Bloemdustria Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and the Novo Transfer scheme, which Brandkop Boesmanskop Bloemspruit Sepane Thaba Nchu are situated in the Upper Orange Catchment. Mo dd De Brug e Seroalo Dam Grootvlei r Newbury Botshabelo Dam Bloemdustria Lovedale DESCRIPTION Kgabanyana Dam W Kle Rustfontein in Lesaka Dam Modder Groothoek The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer schemes are Dam Armenia W Dam two of the three main schemes used to supplement the Riet–Modder Catchment due to Caledon-Bloemfontein the full utilisation of the water resources within the catchment, the third main scheme Ganna being the Orange–Riet Transfer. The Mazelpoort Scheme was developed by Mangaung Leeu Municipality. The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer, Riet-Modder together with the Mazelpoort Scheme situated on the Modder River, form one integrated Catchment Uitkyk DEWETSDORP supply system serving the Mangaung area. SOUTH AFRICA The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme is operated by Bloem Water, REDDERSBURG Caledon LESOTHO and consists of Welbedacht, Rustfontein and Knellpoort dams, along with other service Riet reservoirs, pump stations and water treatment works. Peri-urban area/urban area P P Town Knellpoort 3 The storage capacity of the Welbedacht Dam reduced from 115 million m to approximately Dam Tienfontein International boundary 16 million m3 in only 20 years due to siltation. This impacted the assurance of supply to River and dam Welbedacht Dam Bloemfontein and so Knellpoort Dam was constructed (off channel storage) to augment De Hoek Pipeline and reservoir the supply. -

Schools Address List - Alphabetical Per District 2016 Schools

XHARIEP Section 21 2016 Quintile Hostel Status Educators Learners EMIS Nr. Name of school Language Type Category Postal Address Telephone Physical Address Principal Data Medium nr. Month Schools Address List - Alphabetical per District 2016 Schools District: XHARIEP 443104215 AJC JOOSTE C/S Partly Section 21 Yes Dual: Afr/Eng Public Combined Q1 OSSEWA 38, , PETRUSBURG, 9932 053-5740176 OSSEWASTRAAT 38, PETRUSBURG Mnr JH PRINSLOO October 453 18 441103107 ALBERTINA SISULU S/S Partly Section 21 No English Public Ordinary Sec. Q2 PO BOX 58, EDENBURG, EDENBURG, 9908 051-7431859 1679 PHETLHU STREET, HARASEBEI October 393 12 441103173 AUSTINSPOST PF/S Non-Section 21 No SeSotho Farm Primary Q1 PO BOX 1000, EDENBURG, EDENBURG, 05174-1093 VAALBANK FARM, EDENBURG Ms L.T.D CHAKA October 23 1 9908 443303110 BEANG TSE MOLEMO S/S Section 21 No English Public Ordinary Sec. Q3 PO BOX 21, MATOPORONG, 051-5530676 832 KHUTSO STREET, MATOPORONG Mrs MB MASHOAI Septembe 351 15 REDDERSBURG, 9904 TOWNSHIP r 443203219 BERGMANSHOOGTE I/S Section 21 No Afrikaans Public Intermediate Q3 PO BOX 29, PHILIPPOLIS, PHILIPPOLIS, 051-7730104 ARENDWEG 1, BERGMANSHOOGTE Mnr RMT October 398 16 9970 ENGELBRECHT 442204126 BOARAMELO C/S Partly Section 21 No English Public Combined Q1 PO BOX 31, , JAGERSFONTEIN, 9974 051-7240304 1295 SEEKOEI STREET, ITUMELENG Mr. M.J RADEBE Septembe 825 30 LOCATION r 445203174 BOKAMOSO/IKAMVA IF/S Partly Section 21 No English Farm Intermediate Q1 PO BOX 22, Boesmanksop, Zastron, 9951 051-6731038 Main Road, BOESMANSKOP MR RJ MOFAMMERE October 70 5 441103256 BOTLE BA THUTO P/S Partly Section 21 No English Public Primary Q2 PO BOX 54, HA-RASEBEI, EDENBURG, 9908 051-7431803 1044 VELEKO STREET, HARASEBEI Mr MW LEEUW October 847 25 442304245 DIAMANTHOOGTE C/S Section 21 Yes Afrikaans Public Combined Q2 PO BOX 97, KOFFIEFONTEIN, 053-2050194 FIRST AVENUE, DIAMANTHOOGTE Mr. -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

2020 Gauteng Combine Race Programmes

Gauteng Racing Programmes - 2020 # Date GRPC PWDC TRPF GPU OERF VPU Combine Lib Time A 23.05.2020 Ventersburg Ventersburg Ventersburg Ventersburg Ventersburg n/a n/a 07h30 1 30.05.2020 Winburg 1 Winburg 1 Winburg 1 Theunissen 1 Winburg 1 n/a n/a 08h00 2 Winburg 2 Winburg 2 Winburg 2 Theunissen 2 Winburg 2 Winburg n/a 08h45 3 06.06.2020 Verkeerdevlei 1 Winburg 3 Verkeerdevlei 1 Winburg 1 Verkeerdevlei 1 Glen 1 n/a 08h00 4 Verkeerdevlei 2 Winburg 4 Verkeerdevlei 2 Winburg 2 Verkeerdevlei 2 Glen 2 n/a 08h45 5 13.06.2020 Bloemfontein 1 Bloemfontein 1 Bloemfontein 1 Bloemfontein 1 Bloemfontein 1 Bloemfontein 1 Combine 08h00 6 Bloemfontein 2 Bloemfontein 2 Bloemfontein 2 Bloemfontein 2 Bloemfontein 2 Bloemfontein 2 Combine 08h45 7 20.06.2020 Dewetsdorp 1 Dewetsdorp 1 Dewetsdorp 1 Dewetsdorp 1 Dewetsdorp 1 Dewetsdorp 1 Combine 08h00 8 Dewetsdorp 2 Dewetsdorp 2 Dewetsdorp 2 Dewetsdorp 2 Dewetsdorp 2 Dewetsdorp 2 Combine 08h45 9 27.06.2020 Tierpoort 1 Bloemfontein 3 Bloemfontein 3 Bloemfontein 3 Tierpoort 1 Tierpoort 1 n/a 08h00 10 Tierpoort 2 Bloemfontein 4 Bloemfontein 4 Bloemfontein 4 Tierpoort 2 Tierpoort 2 n/a 08h45 11 04.07.2020 Reddersburg 1 Dewetsdorp 3 Dewetsdorp 3 Reddersburg 1 Reddersburg 1 Trompsburg 1 n/a 08h00 12 Reddersburg 2 Dewetsdorp 4 Dewetsdorp 4 Reddersburg 2 Reddersburg 2 Trompsburg 2 n/a 08h45 13 11.07.2020 Smithfield 1 Smithfield 1 Smithfield 1 Smithfield 1 Smithfield 1 Smithfield 1 Combine 07h30 14 Smithfield 2 Smithfield 2 Smithfield 2 Smithfield 2 Smithfield 2 Smithfield 2 Combine 08h15 15 18.07.2020 Trompsburg 1 Trompsburg -

Rural Planning in South Africa: a Case Study

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Strategies, Planning and Assessment Programme Environmental Planning Issues No. 22, December 2000 Rural Planning in South Africa: A Case Study By Khanya – managing rural change A Report to the UK Department for International Development (Research contract: R72510 Khanya – managing rural change 17 James Scott Street, Brandwag, Bloemfontein 9301 Free State, South Africa Tel: +27-51-430-0712; Fax: +27-51-430-8322 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.khanya-mrc.co.za IIED 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Tel: +44-171-388-2117; Fax: +44-171-388-2826 Contact email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iied.org ISBN: 1 899825 75 4 NOTE This manuscript was completed in November 1999. It has not been possible to include any updates to the text to reflect any changes that might have occurred in terms of legislation, institutional arrangements and key issues. RURAL PLANNING REPORTS This report is one of a suite of four prepared for a study of rural planning experience globally, and published by IIED in its Environmental Planning Issues series: Botchie G. (2000) Rural District Planning in Ghana: A Case Study. Environmental Planning Issues No. 21, International Institute for Environment and Development, London Dalal-Clayton, D.B., Dent D.L. and Dubois O. (1999): Rural Planning in the Developing World with a Special Focus on Natural Resources: Lessons Learned and Potential Contributions to Sustainable Livelihoods: An Overview. Report to UK Department for International Development. Environmental Planning Issues No.20, IIED, London Khanya-mrc (2000) Rural planning in South Africa: A case study. -

Naledi Local Municipality Sponsored Profile

NALEDI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY SPONSORED PROFILE POSTAL: Private Bag X1, Dewetsdorp, 9940 | PHYSICAL: 13 Brand Street, Dewetsdorp TEL: 051 541 0012 | FAX: 051 541 0556 Mr Thabang Moses Cllr Mpolokeng Mahase Cllr Gift Tladi Mr Q W Lefora CHIEF FINANCIAL MAYOR CHIEF WHIP MUNICIPAL MANAGER OFFICER VISION Institutional Profile-Political Component (Plenary Council) The Municipality views the vision and mission statements as The Council of Naledi Local Municipality consists of a total of a critical component for development. This is because certain eight councillors, four of which are ward councillors and four are steps were to be followed to have a credible vision and mission proportional representative councillors. Only the Mayor/Speaker statement developed. is full-time. The vision developed by the Municipality reads as follows: ‘A constantly progressive municipality where quality services and Composition, Boundaries and Size a healthy and safe environment empower a harmonised community Naledi is situated in the south-eastern Free State, and forms part to develop their own economic security in a sustainable local of Xhariep District Municipality. The Local Municipality area future for all.’ measures 3 424km2 and comprises the former Traditional Local Councils (TLCs) of Dewetsdorp, Wepener, Van Stadensrus, as well MISSION as a part of the former south-east, central-south and Bloem area To work as a committed team towards achieving the Municipality’s District TLCs. objectives by means of the following: • ensuring effective communication and consultation between POPULATION all stakeholders Population increase is important because it creates a market for • improving our capacity in terms of resources goods and services, resulting in economic growth, which will • absolute commitment towards the implementation of our hopefully lead to employment opportunities.