From Saul to Paul: the Apostle's Name Change and Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Corinthians – Lesson 1

1 Corinthians – Lesson 2 Introductory Material: Written by the apostle Paul to the church of God at Corinth approximately 55-57 A.D. from Ephesus. Simple Outline: Division (chapters 1-4) Incest (5) Lawsuits/Prostitutes (6) *Sex and Marriage (7) “Now concerning” *Idol meat (8-10) “Now concerning” Veils/Abuse of the Lord’s Supper (11) *Spiritual Gifts (12-14) “Now concerning” Resurrection (15) *Contribution/Conclusion (16) “Now concerning” (* – Asked by the Corinthians) Detailed Outline: I. INTRODUCTION (1:1–9) A. Salutation (1:1–3) B. Thanksgiving (1:4–9) II. IN RESPONSE TO REPORTS (1:10–6:20) A. A Church Divided—Internally and Against Paul (1:10–4:21) 1. The Problem—Division over Leaders in the Name of Wisdom (1:10–17) 2. The Gospel—a Contradiction to Wisdom (1:18–2:5) a. God’s folly—a crucified Messiah (1:18–25) b. God’s folly—the Corinthian believers (1:26–31) c. God’s folly—Paul’s preaching (2:1–5) 3. God’s Wisdom—Revealed by the Spirit (2:6–16) 4. On Being Spiritual and Divided (3:1–4) 5. Correcting a False View of Church and Ministry (3:5–17) a. Leaders are merely servants (3:5–9) b. The church must be built with care (3:10–15) c. Warning to those who would destroy the church, God’s temple in Corinth (3:16–17) 6. Conclusion of the Matter—All are Christ’s (3:18–23) 7. The Corinthians and Their Apostle (4:1–21) a. On being a servant and being judged (4:1–5) b. -

Ethics Commission Agenda

City of Clarksville Ethics Commission August 24, 2021, 4:00 p.m. City Hall, 1 Public Square, 4th Floor Clarksville, TN AGENDA Commission Members: Anthony Alfred Bridgett Childs David Kanervo Mark Rassas Gregory Stallworth 1. Call to Order – Chairperson Childs 2. Introduction of Dr. Gregory Stallworth – Paige Lyle 3. Overview of the role of the Ethics Commission and summary of matters pending before the Commission – Saul Solomon/Paige Lyle 4. Election of Vice-Chair of the Ethics Commission – Chairperson Childs 5. Approval of the minutes of the May 26, 2021 Meeting – Chairperson Childs 6. Adoption of written decision from May 26, 2021 Meeting – Paige Lyle 7. Discussion of January 15, 2021 Complaint brought by Jeff Robinson against Mayor Pitts, Lance Baker, and Saul Solomon – Chairperson Childs 8. Discussion of hearing procedures and scheduling – Paige Lyle / Chairperson Childs 9. Next Steps – Chairperson Childs 10. Other Business 11. Adjournment ETHICS COMMISSION MAY 26, 2021 MINUTES CALL TO ORDER The Ethics Commission meeting was called to order by Chairperson Childs on May 26, 2021, at 4:00 p.m. at City Hall. ATTENDANCE Bishop Anthony Alfred, Ms. Bridget Childs, Dr. David Kanervo, Mr. Mark Rassas. Also Present: Mr. Lance Baker, Mr. Josh Beal, Ms. Stephanie Fox, Ms. Paige Lyle, Mr. Bill Purcell, Mr. Jimmy Settle, Mr. Saul Solomon, Mr. Richard Stevens. INTRODUCTION OF NEW COMMISSION MEMBER AND NOTICE OF RESIGNATION Dr. David Kanervo was introduced to the Commission. He was appointed by the Mayor and confirmed by the City Council to fill the vacant seat left by Mr. Pat Young’s resignation. He provided his background and the other Commission members in attendance made their introductions. -

The Early Christian Church

The African Presence in the Bible T uBlack History Month uTonight’s Topic u“Early Christian Church” The Purpose of Tonight’s Lesson u Dispel the myths that we were introduce to Christianity through slavery. u As well as rebuke the false claim that Christianity is a “White’s Man Religion” u There are a significant number of educated blacks who believe these untruth. u So, tonight, we will search the scriptures for truth. The Sources for Tonight’s Lesson are: Let’s Get Started u When did the Christian Church Begin or When Did It Start? u How did the Christian Church Start? u Where in the bible does it tell us about the beginning of the Christian Church? Acts Chapter 2 (1-47) u And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. In the Jewish calendar, the Feast of Weeks, or the Day of Pentecost, is fifty days after the Passover. It was on the Day of Pentecost after Jesus' death and resurrection when the Holy Spirit was poured out on Jesus' followers that the church began Acts 2 (2-5) u 2 And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. u 3 And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. u 4 And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. -

Acts 13:1-12

a Grace Notes course The Acts of the Apostles an expositional study by Warren Doud Lesson 214: Acts 13:1-12 Grace Notes 1705 Aggie Lane, Austin, Texas 78757 Email: [email protected] ACTS, Lesson 214, Acts 13:1-12 Contents Acts 13:1-12 ................................................................................................................. 3 Acts 13:1 .......................................................................................................................... 3 Acts 13:2 .......................................................................................................................... 4 Acts 13:3 .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acts 13:4 .......................................................................................................................... 6 Acts 13:5 .......................................................................................................................... 7 Acts 13:6 .......................................................................................................................... 8 Acts 13:7 .......................................................................................................................... 9 Acts 13:8 .........................................................................................................................10 Acts 13:9 .........................................................................................................................10 -

M=Missionary Journey Begins Acts 13

M=Missionary journey Begins Acts 13 Missionary: a person who goes out to spread the good news of Jesus Paul & Barnabas began their first missionary journey in Acts 13. When they came to a new city, they usually went first to a synagogue where they could talk to the Jews. Chapter 13 is the beginning of Paul’s missionary journeys. This chapter is also important because Paul becomes the main character of Acts, and Peter slips into the background. Christians were in Antioch worshipping. Antioch is significant because Christians were first called Christians here. Acts 11:26. This was also the first church that was mission minded. While worshipping, the Holy Spirit picked Paul and Barnabas to start preaching abroad. The men there fasted, prayed and put their hands on them and sent them off. John Mark also traveled with them. They sail to the island of Cyprus and travel through it to Paphos on the western side of it. They meet a sorcerer and false prophet named Bar-Jesus aka Elymas. The proconsul (governor) of the city Sergious Paulus wanted to hear Paul, but Elymas didn’t want him to. So Paul filled with the Holy Spirit lets Elymas have it, and then Elymas is blinded for some time! Because of this the proconsul believed. John returns home to Jerusalem. This is important because in Acts 15:38 Barnabas wants to take John again and Paul doesn’t think it is wise because John deserted them in Pamphylia. But we see in II Timothy 4 they had worked out their disagreement. -

Of the Apostles the Building of the Church

OF THE APOSTLES THE BUILDING OF THE CHURCH INVER GROVE CHURCH OF CHRIST FALL 2019 THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES Acts 1 The Promise of the Holy Spirit LESSON 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK The former treatise have I made, O Theophilus, of all that Jesus began both to do and teach, (2) Until the Author: Unlike Paul’s Epistles, the Author of Acts does day in which he was taken up, after that he through the not name himself. The use of the personal pronoun “I” Holy Ghost had given commandments unto the apostles in the opening sentence, seems to indicate the books whom he had chosen: (3) To whom also he shewed first recipients must have known the writer. The himself alive after his passion by many infallible proofs, beginning of this book and the third gospel have been being seen of them forty days, and speaking of the accepted as from Luke. things pertaining to the kingdom of God: (4) And, being assembled together with them, commanded them that Date: Seems that the book was written before outcome they should not depart from Jerusalem, but wait for the of the trial Paul went through, around 61 AD. promise of the Father, which, saith he, ye have heard of Purpose: The book of Acts , mainly the acts of Peter me. (5) For John truly baptized with water; but ye shall and Paul, mostly Paul. Paul was an Apostle to Gentiles. be baptized with the Holy Ghost not many days hence. Rom 11:13 For I speak to you Gentiles, inasmuch as I The Ascension am the apostle of the Gentiles, I magnify mine office: (6) When they therefore were come together, they We will see the Wonderful Work among the Nations asked of him, saying, Lord, wilt thou at this time restore come to the gospel call, the Household of God passes again the kingdom to Israel? (7) And he said unto from being a National institution to an International them, It is not for you to know the times or the seasons, World Institution. -

Acts 13:1–13)

Acts 13-28b 8/19/96 2:04 PM Page 1 The Character of an Effective Church 1 (Acts 13:1–13) Now there were at Antioch, in the church that was there, prophets and teachers: Barnabas, and Simeon who was called Niger, and Lucius of Cyrene, and Manaen who had been brought up with Herod the tetrarch, and Saul. And while they were min- istering to the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for Me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” Then, when they had fasted and prayed and laid their hands on them, they sent them away. So, being sent out by the Holy Spirit, they went down to Seleucia and from there they sailed to Cyprus. And when they reached Salamis, they began to proclaim the word of God in the synagogues of the Jews; and they also had John as their helper. And when they had gone through the whole island as far as Paphos, they found a certain magician, a Jewish false prophet whose name was Bar-Jesus, who was with the proconsul, Sergius Paulus, a man of intelli- gence. This man summoned Barnabas and Saul and sought to hear the word of God. But Elymas the magician (for thus his name is translated) was opposing them, seeking to turn the pro- consul away from the faith. But Saul, who was also known as Paul, filled with the Holy Spirit, fixed his gaze upon him, and said, “You who are full of all deceit and fraud, you son of the 1 Acts 13-28b 8/19/96 2:04 PM Page 2 13:1–13 ACTS devil, you enemy of all righteousness, will you not cease to make crooked the straight ways of the Lord? And now, behold, the hand of the Lord is upon you, and you will be blind and not see the sun for a time.” And immediately a mist and a darkness fell upon him, and he went about seeking those who would lead him by the hand. -

Holy Trinity & St. Michael

Kewaskum Catholic Parishes of Holy Trinity & St. Michael Staff Holy Trinity & St. Michael Shared Pastor www.kewaskumcatholicparishes.org Rev. Jacob A. Strand Holy Trinity Office –Ext. 104 Deacon: Rev. Mr. Ralph Horner St. Michael Office – 262-334-5270 Cell Phone – 262-343-1795 [email protected] Hours: Wednesdays 6:30pm—8pm Holy Trinity Church 305 Main Street P.O. Box 461 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-626-2860 Fax – 262-626-2301 Dir. of Admin Services– Mrs. Nancy Boden Ext. 106 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Ext. 105 [email protected] St. Michael Church 8883 Forest View Road Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-334-5270 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Holy Trinity School 305 Main Street P.O. Box 464 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone 262-626-2603 Website: www.htschool.net Principal – Mrs. Amanda Longden Ext. 101 [email protected] School Secretary—Mrs. Angela Schickert Ext. 100—[email protected] Faith Formation Program Phone 262-626-2650 WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE DAILY MASS SCHEDULE Dir. of Faith Formation/Coordinator for K—8th Grade—Mrs. Mary Breuer Saturday 4:00 p.m.—St. Michael Tuesdays 5:00 p.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] Sunday 7:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Wednesdays 6:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Associate Director/Coordinator for H.S. Sunday 9:00 a.m.—St. Michael Thursdays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity Youth Ministry—Mrs. Jessica Herriges Sunday 11:00 a.m.—Holy Trinity Fridays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION EUCHARSTIC ADORATION Joint Pastoral Council Chair Mrs. -

President's Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families

President’s Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families, Happy Feast of Sts. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels! Yesterday we celebrated our patronal feast and the 3rd anniversary of the dedication of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Chapel. As our fourth year is now underway, we can look back and celebrate the many accomplishments of SMA in the past and look forward to our exciting future together, confident that our patron, St. Michael, will defend us in the battle. Whenever I visit the doctor, there are four words I never like to hear: “Now this may hurt.” That message brings about two responses in me, the first is one of dread… it means I’m going to be experiencing something I really don’t want! Secondly, I brace in anticipation of what is about to happen; I’m able to make myself ready for the event. September is the month of Our Lady of Sorrows (in Latin, the seven “dolors”). When Mary encountered Simeon in the temple, she heard the same message in a more intense form, “this is going to hurt.” The prophet told her, A sword will pierce through your own soul. Mary, a new mother still in wonder at the miraculous birth of her child, now hears that her life is going to be integrally tied to his sufferings. So September is always a month linked to compassion; the compassion Mary had for her son and has for us. It is also a reminder of the compassion we can have for each other. -

St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY

SEPTEMBER Activity 6 St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY Age level: All ages Recommended time: 10 minutes What you need: St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book), SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel (optional), colored pencils and/or markers, and scissors Activity A. Explain to your students that we have been learning that the Devil and his fallen angels tempt us to sin. We can pray a special, very powerful prayer to St. Michael to help us combat these evil spirits. St. Michael is not a saint, but an archangel. The archangels are leaders of the other angels. According to both Scripture and Catholic Tradition, St. Michael is the leader of the army of God. He is often shown in paintings and iconography in a scene from the book of Revelation, where he and his angels battle the dragon. He is the patron of soldiers, policemen, and doctors. B. Have your students turn to St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book) and pray together the prayer to St. Michael the Archangel. You may wish to play a sung version of the prayer, which you can find at SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel. C. Finally, have your students color in the St. Michael shield and attach it to their prayer boards. © SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us St. Michael the Archangel protects us against danger and the Devil. He is our defense and our shield and the Church has given us a special prayer so that we can ask him for help. -

FROM PENTECOST to PRISON Or the Acts of the Apostles

FROM PENTECOST TO PRISON or The Acts of the Apostles Charles H. Welch 2 FROM PENTECOST TO PRISON or The Acts of the Apostles by Charles H. Welch Author of Dispensational Truth The Apostle of the Reconciliation The Testimony of the Lord's Prisoner Parable, Miracle, and Sign The Form of Sound Words Just and the Justifier In Heavenly Places etc. THE BEREAN PUBLISHING TRUST 52A WILSON STREET LONDON EC2A 2ER First published as a series of 59 articles in The Berean Expositor Vols. 24 to 33 (1934 to 1945) Published as a book 1956 Reset and reprinted 1996 ISBN 0 85156 173 X Ó THE BEREAN PUBLISHING TRUST 3 Received Text (Textus Receptus) This is the Greek New Testament from which the Authorized Version of the Bible was prepared. Comments in this work on The Acts of the Apostles are made with this version in mind. CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 THE BOOK AS A WHOLE............................................................... 6 2 THE FORMER TREATISE The Gentile in the Gospel of Luke ........................................ 8 3 LUKE 24 AND ACTS 1:1-14........................................................ 12 4 RESTORATION The Lord’s own teaching concerning the restoration of the kingdom to Israel .......................................................... 16 The question of Acts 1:6. Was it right?............................... 19 The O.T. teaching concerning the restoration of the kingdom to Israel .......................................................... 19 5 THE HOPE OF THE ACTS AND EPISTLES OF THE PERIOD................ 20 Further teaching concerning the hope of Israel in Acts 1:6-14............................................................... 22 6 THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE ACTS AND ITS WITNESS Jerusalem - Antioch - Rome................................................ 26 7 RESTORATION, RECONCILIATION, REJECTION The three R’s..................................................................... -

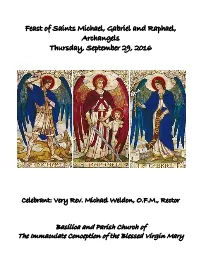

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016 Celebrant: Very Rev. Michael Weldon, O.F.M., Rector Basilica and Parish Church of The Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary The Angelus V. The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary: R. And she conceived by the Holy Spirit. Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. V. Behold the handmaid of the Lord: R. Be it done unto me according to thy word. Hail Mary... V. And the word was made flesh: R. And dwelt among us. Hail Mary... V. Pray for us, O Holy Mother of God. R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ. Pour forth, we beseech thee, O Lord, thy grace into our hearts, that we to whom the incarnation of Christ Thy Son was made known by the message of an angel, may by His Passion and Cross be brought to the glory of His resurrection; through the same Christ our Lord. Amen. Entrance Chant Michael, Prince of All the Angels Michael, prince of all the angels, Gabriel, messenger to Mary, While your legions fill the sky, Raphael, healer, friend and guide, All victorious over Satan, All you hosts of guardian angels Lift your flaming sword on high; Ever standing by our side, Shout to all the seas and heavens: Virtues, Thrones and Dominations, Now the morning is begun; Raise on high your joyful hymn, Now is rescued from the dragon Principalities and Powers, She whose garment is the sun! Cherubim and Seraphim! Mighty champion of the woman, Mighty servant of her Lord, Come with all your myriad warriors, Come and save us with your sword; Enemies of God surround us: Share with us your burning love; Let the incense of our worship Rise before His throne above! Gloria Gospel Acclamation Sanctus Mystery of Faith Amen Agnus Dei Prayer to St.