Issue: 2, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report

AB InBev annual report 2018 AB InBev - 2018 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report Shaping the future. 3 Bringing People Together for a Better World. We are building a company to last, brewing beer and building brands that will continue to bring people together for the next 100 years and beyond. Who is AB InBev? We have a passion for beer. We are constantly Dreaming big is in our DNA innovating for our Brewing the world’s most loved consumers beers, building iconic brands and Our consumer is the boss. As a creating meaningful experiences consumer-centric company, we are what energize and are relentlessly committed to inspire us. We empower innovation and exploring new our people to push the products and opportunities to boundaries of what is excite our consumers around possible. Through hard the world. work and the strength of our teams, we can achieve anything for our consumers, our people and our communities. Beer is the original social network With centuries of brewing history, we have seen countless new friendships, connections and experiences built on a shared love of beer. We connect with consumers through culturally relevant movements and the passion points of music, sports and entertainment. 8/10 Our portfolio now offers more 8 out of the 10 most than 500 brands and eight of the top 10 most valuable beer brands valuable beer brands worldwide, according to BrandZ™. worldwide according to BrandZTM. We want every experience with beer to be a positive one We work with communities, experts and industry peers to contribute to reducing the harmful use of alcohol and help ensure that consumers are empowered to make smart choices. -

Indies Entry Process 2019

INDIES ENTRY PROCESS 2019 Independent Brewers Association PO Box 138, Fitzroy VIC 3065 iba.org.au ABN: 96 866 105 506 +61 3 9417 3105 brewcon.org.au [email protected] Table of Contents The Independent Beer Awards Aus. (the Indies) ........................................................................................ 2 Indies 2019 Key Dates ....................................................................................................................... 2 Eligibility .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Brewery Eligibility ................................................................................................................................. 3 Australian independent breweries .................................................................................................... 3 Eligibility compliance........................................................................................................................ 3 Beer Entry Eligibility ............................................................................................................................. 3 Judging Process ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Judge Selection ................................................................................................................................... 4 Judging Process ................................................................................................................................. -

Bar Tending Draft

The Hospitality Handbook Series Volume 3 Know Your Beers A Guide to Alcoholic Drinks, Drinking Culture and the Hospitality Industry in Australia INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 KNOW YOUR BEERS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 WHAT IS BEER? ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 WHAT ARE THE IMPORTANT THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT BEER? ................................................................................. 4 KNOW WHAT YOU’RE TALKING ABOUT... ....................................................................................................................... 5 TYPES OF BEER ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 FAMOUS AUSTRALIAN BRANDS AND REGIONS ......................................................................................................... 10 FOOD MATCHING TIPS .................................................................................................................................................. 12 BEER CULTURE ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert's Report In

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert’s Report in relation to the Proposed Demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (ABN 28 050 036 372) 17 March 2011 GRANT SAMUEL & ASSOCIATES LEVEL 6 1 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 T: +61 3 9949 8800 / F: +61 3 99949 8838 www.grantsamuel.com.au Financial Services Guide Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (“Grant Samuel”) holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 240985 authorising it to provide financial product advice on securities and interests in managed investments schemes to wholesale and retail clients. The Corporations Act, 2001 requires Grant Samuel to provide this Financial Services Guide (“FSG”) in connection with its provision of an independent expert’s report (“Report”) which is included in a document (“Disclosure Document”) provided to members by the company or other entity (“Entity”) for which Grant Samuel prepares the Report. Grant Samuel does not accept instructions from retail clients. Grant Samuel provides no financial services directly to retail clients and receives no remuneration from retail clients for financial services. Grant Samuel does not provide any personal retail financial product advice to retail investors nor does it provide market-related advice to retail investors. When providing Reports, Grant Samuel’s client is the Entity to which it provides the Report. Grant Samuel receives its remuneration from the Entity. In respect of the Report in relation to the proposed demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited (“Foster’s”) (“the Foster’s Report”), Grant Samuel will receive a fixed fee of $700,000 plus reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for the preparation of the Report (as stated in Section 8.3 of the Foster’s Report). -

Beer Knowledge – for the Love of Beer Section 1

Beer Knowledge – For the Love of Beer Beer Knowledge – For the Love of Beer Contents Section 1 - History of beer ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Section 2 – The Brewing Process ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 3 – Beer Styles .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Section 4 - Beer Tasting & Food Matching ...................................................................................................................... 19 Section 5 – Serving & Selling Beer .................................................................................................................................. 22 Section 6 - Cider .............................................................................................................................................................. 25 Section 1 - History of beer What is beer? - Simply put, beer is fermented; hop flavoured malt sugared, liquid. It is the staple product of nearly every pub, club, restaurant, hotel and many hospitality and tourism outlets. Beer is very versatile and comes in a variety of packs; cans, bottles and kegs. It is loved by people all over the world and this world wide affection has created some interesting styles that resonate within all countries -

Carnival's Private Label Beers Arrive in Australia

CHEERS! CARNIVAL’S PRIVATE LABEL BEERS ARRIVE IN AUSTRALIA Responding to Australia’s growing passion for craft beers, Carnival Cruise Line now offers ParchedPig Toasted Amber Ale, West Coast IPA and ThirstyFrog Caribbean Wheat on its Australia- based ships. SYDNEY (11 June, 2019) – Building on the growing demand for craft beer in Australia, Carnival Cruise Line has become the first cruise line to can and keg its own private label beers crafted by Brewmaster Colin Presby and the in-house brewery team aboard Carnival Horizon and Carnival Vista. “With the success of our breweries on Carnival Vista and Carnival Horizon, the obvious next step was to let all of our guests fleetwide including Australia, enjoy our refreshing craft beers,” said Edward Allen, Carnival’s Vice President of Beverage Operations. “We are pleased to be the first cruise line to scale up its beverage operations by canning and kegging our own beer. My hope is that our Australian guests will enjoy a refreshing beer on the top decks and then take a four-pack home with them to share with family and friends as a tasty reminder of their cruise.” The three beers, which are based on recipes developed by Brewmaster Colin Presby and the Carnival brewery team, are now available in cans on Carnival’s Australia-based ship, Carnival Spirit. They will also be available on Carnival Splendor, the newest and largest ship to be homeported in Australia, when she arrives through the Sydney Heads in December. The beers include: • ThirstyFrog Caribbean Wheat - an unfiltered wheat beer with flavors of orange and spices. -

Brewcon 2018! 9:15 AM: KEYNOTE – Kim Jordan, Founder and Executive Chair, New Belgium Brewing

PROGRAM DETAIL PLENARY SESSIONS WEDNESDAY 27 JUNE 2018 9:00 AM: WELCOME to BrewCon 2018! 9:15 AM: KEYNOTE – Kim Jordan, Founder and Executive Chair, New Belgium Brewing KIM JORDAN – BIOG Kim Jordan, Co-founder, Executive Chair of the Board and former CEO of New Belgium Brewing, has developed expertise at the intersection of business, the environment and community to create one of the most respected craft breweries and innovative businesses in America. Her lifelong commitment to developing healthy communities has informed New Belgium's culture through progressive policies like employee ownership, open- book management, and philanthropic giving. In more than a quarter century as an entrepreneur, Kim has spoken to thousands of people in the business, nonprofit, and academic worlds about how to create a vibrant and rewarding work culture that enhances the bottom line. Kim has been a director on many diverse Boards over the years including The Brewers Association, 1% for The Planet and The Governor’s Renewable Energy Authority Board. She currently participates on the Board of Governors for Colorado State University, and the Advanced Energy Economy. She serves on Boards where she believes her progressive business philosophy can make a difference on important issues. Now as the Executive Chair, Kim serves as a link between New Belgium’s highly competent and engaged management group and its Board of Directors. She continues to champion foundational aspects of New Belgium that make it a business role model with fresh thinking about progressive business practices and the marketplace of the future. Kim works to represent New Belgium, speaking with brewers, business people and legislators about the power of progressive business to make positive change in the world. -

Cicerone® Certification Program Australia & New Zealand Certified Beer Server Syllabus

Cicerone® Certification Program Australia & New Zealand Certified Beer Server Syllabus Updated 1 June 2019 This syllabus outlines the knowledge required of those preparing for the Certified Beer Server exam in Australia and New Zealand (for syllabi pertaining to other regions, visit cicerone.org). While this list is comprehensive in its scope of content, further study beyond the syllabus is necessary to fully understand each topic. The content tested on the Certified Beer Server exam is a subset of the information presented within the Master Cicerone® syllabus, and individual syllabi for all four levels of the program may be found on the cicerone.org website. Outline (Full syllabus begins on next page.) I. Keeping and Serving Beer A. Beer distribution B. Serving alcohol C. Beer storage D. Draught systems E. Beer glassware F. Serving bottled beer G. Serving draught beer II. Beer Styles A. Understanding beer styles B. Style parameters C. Beer style knowledge III. Beer Flavour and Evaluation A. Taste and flavour B. Identify normal flavours of beer and their source C. Off-flavour knowledge IV. Beer Ingredients and Brewing Processes A. Ingredients V. Pairing Beer with Food Appendix A – Australian Beer Styles © Copyright 2019, Cicerone® Certification Program For more information, visit cicerone.org or email [email protected] Cicerone® Certification Program Version 4.0 – 1 June 2019 Certified Beer Server Syllabus – Page 2 Full Syllabus I. Keeping and Serving Beer A. Beer distribution 1. Various parties participate in the production and delivery of beer in Australia and New Zealand a. Brewery – brews and packages beer into kegs, bottles, cans, etc. -

Judgment Template

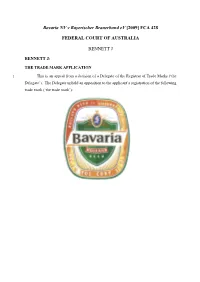

Bavaria NV v Bayerischer Brauerbund eV [2009] FCA 428 FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA BENNETT J BENNETT J: THE TRADE MARK APPLICATION 1 This is an appeal from a decision of a Delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks (‘the Delegate’). The Delegate upheld an opposition to the applicant’s registration of the following trade mark (‘the trade mark’): 2 It is apparent that the trade mark contains a reference to a place, Bavaria, which is associated with the brewing of beer. The question is whether the trade mark, which contains that word, should be registered. 3 There is an endorsement on the trade mark application which provides that when the trade mark is used for items in the specification of goods other than beer, the word “Beer” in the trade mark will be changed to accord with those other items. For example, if the product were juice, the word “Beer” would be replaced with the word “Juice”. The case has been conducted on the basis of the proposed registration for beer. THE PARTIES The applicant 4 The applicant for registration of the trade mark, the applicant in this appeal, is Bavaria NV, a family-owned company incorporated in The Netherlands that manufactures beer and other alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. 5 By an application filed on 22 August 2000, Bavaria NV seeks registration of the trade mark in respect of Classes 32 and 33 for, inter alia, beer and other beverages. 22 August 2000 is the priority date of the application. 6 Bavaria NV is a significant producer of beer both locally in The Netherlands and for export from The Netherlands. -

Position Statement: Zero Alcohol Products

POSITION STATEMENT: Zero alcohol products DEFINITIONS JANUARY 2020 Zero alcohol products: beverages that contain 0.5% or less alcohol by volume (ABV), yet retain the trademark name ISSUE OVERVIEW and branding of alcohol products, and/or mimic Alcohol industry analysis reports have identified the growing the flavour of alcohol popularity of zero alcohol products among Australian products. While it is consumers.3 At present in Australia, a limited range of non- recognised that at 0.5% alcoholic beer, cider, wine and spirit brands are available.4 ABV these products Alcohol companies such as Carlton United Breweries may not represent a truly (CUB), Lion, Coopers, and Diageo are some of the current alcohol-free product, producers of these products.4,5,6,7 Zero alcohol products are 0.5% ABV was chosen available from independent distributors, alcohol retailers, and as products above this major supermarkets nationally.4,5,8,9 The sale of non-alcoholic level are required to beer products in Australia has increased by 57 per cent include a statement of to $35.5 million over the last five years.10 Uptake of these the number of standard products has been significant, with industry market research drinks in the package. reporting a ten-fold increase in non-alcoholic beer sales at CUB, and a higher proportion of female consumers than for Alcohol brand alcoholic beer.6,11 extension: the application of a current Although these products provide an alternative to alcoholic product brand name products, the packaging and unrestricted availability of zero to a new product in alcohol products presents cause for concern, particularly a different product because they share branding and product packaging with category and/or target alcoholic products. -

Untapping Sustainability Trends in Australian Craft Breweries

It’s the yeast we can do: Untapping Sustainability Trends in Australian Craft Breweries David M. Herold (corresponding author) Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport , QLD, Australia Farai Manwa, Suman Sen, Simon Wilde Southern Cross University, Australia 1. Introduction Beer is a product with a simple core recipe: malt, yeast, hops and water. The transformation of these ingredients in varying proportions and application of varying brewing techniques into alcoholic beverage represents a multi–million dollar beer industry. The entry of craft beers into the industry has further expanded the range of beer styles available in the market. In Australia alone, the beer industry produced more than 18 million hectolitres in 2015, generating more than AUD$4.8 billion in revenue. While the overall consumption of beer in Australia is decreasing, the craft beer industry has achieved double–digit growth rates over the last five years (IBISWorld, 2015). Page 82 © 2016 Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Vol XII, Iss 2, August 2016 RossiSmith Academic Publications, Oxford/UK, www.publicationsales.com In general, beer is perceived as a sustainable product as the main ingredients are naturally and organically produced (Schaltegger, Viere & Zvezdov, 2012). However, the impressive volume of beer production and consumption in Australia and elsewhere comes at a cost. It employs a brewing process that is very water and energy–intensive, thereby leaving a relatively large carbon footprint on the environment through contamination of nearby soil and water bodies, and emission of anthropogenic gases in the air (Fish, 2015). From an academic perspective, very limited research on sustainability in entrepreneurial craft breweries has been undertaken and is mostly US–centric. -

Coopers Annual Report 2020.Pdf

Annual Report 2020 COOPERS BREWERY LTD PO Box 46, Regency Park SA 5942 WE ARE FAMILY ABN 13 007 871 409 Telephone 08 8440 1800 461 South Road, Regency Park SA 5010 coopers.com.au TO OUR STAFF THANK YOU ALL FOR YOUR DEDICATION, RESILIENCE AND OPTIMISM. WE ARE A FAMILY AND WILL CONTINUE TO FACE THE CHALLENGES TOGETHER. Coopers Annual Report 2020 2 Coopers Annual Report 2020 CONTENTS Highlights ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Managing Director & Chairman’s Report .......................................................................... 6 COVID-19 .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Brewers Association Report .................................................................................................10 Our People ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Institute of Brewing & Distilling Graduates ...................................................................16 New Products ...............................................................................................................................18 Stout Revival .................................................................................................................................23 Awards .............................................................................................................................................24