Examine the Value of Place Names As Evidence for the History, Landscape And, Especially, Language(S) of Your Chosen Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Designer Shopping and Country Living Pdf to Download

Designer shopping and country living Braintree and Great Dunmow routes Total distance of main route is 87km/54miles Cobbs 1 7 5 5 Fenn A Debden 0 B1053 0 1 1 1 Short rides B B 0 1 T B1 7 HA 05 XTED 3 RO A A 9.5km/5.9miles D R i v A B 1 e 1 1 r 24 8 P Finchingfield B 32.8km/20.5miles B 4 a 1 n 3 t 83 Debden C 8.9km/5.5miles Green 51 Hawkspur 10 Green B B 7 1 A 5 0 11 D 23.5km/14.7miles 0 5 2 1 1 3 B 4 3 1 Widdington A E 20km/12.5miles Thaxted Wethersfield 7 F 12.8km/8miles 1 0 Little Bardfield 1 Blackmore A G 13.8km/8.6miles 2 End B ROAD 105 H 32.4km/20.2miles BARDFIELD Great 3 Bardfield I 12.6km/7.9miles 1 m 5 B a 0 7 iver C 1 05 R 1 8 1 B 4 J 14km/8.8miles Cherry Green B Gosfield HALSTEAD N Rotten ORTH HAL End L RD 1 05 1 B1 3 Richmond’s S 1 Attractions along this route H A Shalford A Green L FO RD R Holder’s OA 1 Broxted Church D B r Green Monk 1 e 0 5 2 Henham lm Street Great Bardfield Museum Visitor Centre e 3 h . C 3 1 R Saling Hall Garden 5 7 B 0 1 1 0 B 1 8 1 4 Blake House Craft Centre E 4 1 B A M N A 0 1 L 5 I B1 3 L 0 1 51 S 3 5 L B1051 M A The Flitch Way R 57 LU O 10 P A LU B B D 6 B Great Notley Country Park & Discovery Centre E 1 Lindsell A RHE DGE R GA O L S i L R AD L L N v Broxted LO EN L L A E 7 Braintree District Museum WS GRE IN E e Elsenham D S r Duton Hill P High 1 a 5 1 8 n Garrett Warner Textile Archive Gallery 0 3 Bardfield t 1 1 B Saling A 9 Freeport B B 1 1 0 0 5 10 5 Cressing Temple 7 B PI 3 3 1 L T OO S 8 W 2 R Folly Elsenham 4 O 11 AD 3 Green Pleshey Castle 1 B105 B A Great 12 Hatfield Forest R O Saling B -

File: February-March2020.Pdf

St Andrew’s Church www.tenpennyvillages.uk Find us on fb: ParishChurchesofAlresfordElmsteadThorrington-TennpennyVillages SERVICES • Sunday Morning Services: 11am with crèche for under 3s. Also an 8am service on 1st Sunday of month. • Sunday Evening Services: as advertised • Mid-Week: Morning Prayer every day Monday – Friday except Thursday which is Communion: 9am in the Sanctuary REGULAR GROUPS http://tenpennyvillages.uk/calendar.html Children, Young People & Families • Bumps ‘n’ Babies: Tuesdays in term-time 10.30am to 12 noon in the Hub. • Scramblers for under 5s and their carers: Mondays in term-time 1.45 to 3pm in the Hub. • Razmatazzfor primary aged children: Mondays in term-time 3.30 to 4.30pm in the Hub. • Hangout@theHub: Youth Group for years 6 upwards – Thursday evenings in term-time 6.30-8pm in the Hub. • Messy Church: for the whole family – 3rd Friday of the month 4.30pm in the Church & Hub (or as advertised). Adults • Home Groups: Tuesday evenings, Wednesday afternoons & evenings. • Internet & Book Cafe: fortnightly on a Wednesday, 10am to 12 noon in the Church: (5th & 19th February, 4th & 18th March) • MemoriesCafe: 1st Thursday in the month at 2 - 4pm in the Hub for those suffering with some memory loss and their carers’. For more information, please contact Sue Giles on 01206 826607 • Friendship Circle: 2nd Monday in the month 10.30am - 12 noon in the Hub. • Relax&Renew: Relaxation group 2nd Friday in the month 1.30 to 3pm • Knit ‘n’ Natter: Alternate Tuesdays in the Hub at 2pm (11th & 25th February, 10th & 24th March) CONTACTS: -

Essex a Gricu Ltural Society

Issue 27 Welcome to the Essex Agricultural Society Newsletter September 2016 Rural Question Time 20 April Regardless of the outcome of the referendum on 23rd June, one thing our On Wednesday, the Essex Agricultural farming and rural business clients can Society hosted an important rural question depend on is the continued support of time at Writtle College on the facts behind Gepp & Sons, providing specialist and the 'Brexit' debate and the impact on practical advice on a wide range of legal agriculture and the rural economy. issues. The high profile panel included former NFU CLA East Regional Director Ben Underwood President Sir Peter Kendall; former Minister said: “To campaign or govern without of State for Agriculture and Food Sir Jim giving answers on how the rural economy Paice; CLA East Regional Director Ben will be sustained in the future, whether we Underwood, and the UKIP Leader of leave or remain, undermines confidence Norfolk County Council Richard Coke. and gives concern as to the future security of the rural economy. “The CLA wants Ministers to confirm whether they are prepared for all eventualities following the EU Referendum: if the UK votes to leave, the uncertainties for farming and other rural businesses are immediate and need to be addressed swiftly; if we vote to remain, there are still critical commitments that Ministers will The event was ably chaired by NFU need to make before the next Common Vice-Chairman and Essex farmer, Guy Agricultural Policy budget is agreed in 2020. Smith. “We’re not telling our members how to The timely debate came in the wake of vote, but we make it very clear that we will demands by farmers for more information be fighting to defend their interests about how agriculture would be affected if whatever the outcome. -

Minutes of Great Bentley Patient Participation Group

Minutes of Great Bentley Patient Participation Group Thursday 20th March 2014 Chaired by – Melvyn Cox Present: Charles Brown – Vice Chairman Sharon Batson – Secretary Dr Freda Bhatti – Senior Partner Richard Miller – Practice Manager Approx 50 members present 1. Welcome and Apologies Melvyn Welcomed those present including Dr Shane Gordon Apologies received from Barry Spake 2. Minutes of Last Meeting Agreed 3.Guest Speak – Dr Shane Gordon, GP and Chief Officer, Clinical Commissioning Group The CCG has been in place since April 2013 and is the local NHS statutory body providing hospital and community services in our area, but does not cover general practice as this is provided by NHS England. Big Care Debate – looking at the future of the health service in the Colchester/Tendring areas. 1000 people have been involved in the last 4 months. The main topics are to look at changing the way NHS listens to the people it serves and being more available, and to make local general practice responsible for health services commissioned in the area. Circumstances we find ourselves in 2014 – The Health Service is very protected with regards to funding, services not needed to be slashed as drastically as within Social Services. However the growth in funding is not as fast as the growth in need. More people not working and paying tax, the older you get more medical conditions are likely and therefore costs more money. £400 million allocated to Colchester/Tendring CCG per annum £200 million allocated to NHS England for the area per annum. Under pressure to do more with the same money, £20 million more work in new year with the same money as last year. -

Essex. [Kelly's Masseuse

662 MAS ESSEX. [KELLY'S MASSEUSE. Newman Robart, 2 Walpole villas, METAL MERCHANTS. Winter Miss Nancy Hodges, 10 Mount Dovercourt, Harwich Driver & Ling. Union yard. Chelmsfrd Pleasant road, Saffron WaIden Orchard Hy. 45 Essex rd. Manor Park Palmer George & Sons (wholesale). Osborne G. 26 Hartington rd.Southend Brentwood Parker Robt. 47 Belgrave rd. Ilford White Charles, North rd. Prittlewell MASTER MARINERS. Paton F. 188 Plashet gro. East Ham Pentin John D. 5 Selborne rd. Ilford MIDWIVES. Al·blett J. 3 Station road. Dovercourb Pickthorn Charles W. 40 Endsleigh Cooke Mrs. Jane, 123 King's rd.Halstd Banks Geo. F. 24 Rutland rd. Ilford gardens, llford Doolan Mrs. Mary Ann L.O.S. Great Barnes Edward, York st.Brigbtlingsea, Pittuck Geo. Wm.Wivenhoe,Oolchester Wakering, Southend Colchester Rawlings Joseph, Dean street, Bright- Fowler Mrs. Ellen, 32 Mersea road, Dates William Oharles, Sidney street, lingsea, Oolchester Oolchester Brightlingsea, Oolchester Rayner Geo. Wm. Wivenhoe, Oolchestr Haslehurst Mrs. Oatherine L.O.S. Bonett A. O. 87 Byron ay. Ea. Ham Redwood Joseph, I Oliff view, Oliff Smith street, South Shoebury.Shoe. Bowdell Joseph, Station rd. Brightling- road, Dovercourt, Harwich buryness S.O sea, Colchester Richmond W. J. North st.Rochford 8.0 Lansdell Mrs. Jane, Herbert rd.lIford Oant George 8hipman, Queen 13treet, Robertson Jas. 90 Mayfair ay. Ilford Marchant Miss E .• L.O.S. 73 Pr:nces Brightlingsea, Colchester Shedlock Hy. 10 Lee ter. Dovercourt street, Southend Ohaplin James, Victoria place, Bright- SIlerborne UTn. T .5 Second aV•....m.anor". Pk Mitchell Mrs. Louisa E. 31 Goldlay lingsea. Colchester S·lID mons DW. -

Nomina Bibliography

Nomina - Bibliography Keith Briggs Last modified 2013-12-18 18:44 This file is automatically generated from Nomina.bib, which is itself automatically generated from Nomina_contents.html by a program I wrote myself (Nomina_to_bibtex_01.py). The file Nom- ina_contents.html is itself generated from a plain ascii .txt file by txt_to_html_01.py. The bibli- ography uses a style file JEPNS_biblatex.sty written by me, together with the biblatex package. There are 319 articles here, covering all volumes to 32 (2009). References Adams, G. B. (1979), ‘Prolegomena to the study of surnames in Ireland’, Nomina 3, pp. 81–94. — (1980), ‘Place-names from pre-Celtic languages in Ireland and Britain’, Nomina 4, pp. 46–63. Adams, G. Brendan (1978), ‘Prolegomena to the study of Irish place-names’, Nomina 2, pp. 45–60. Ames, Jay (1981), ‘Appendix: The nicknames of Jay Ames’, Nomina 5, pp. 80–81. Andrews, J. H. (1992-93), ‘The maps of Robert Lythe as a source for Irish place-names’, Nomina 16, pp. 7–22. Anon. (1978), ‘Papers from the Tenth Conference of the Council for Name Studies in Great Britain and Ireland’, Nomina 2, p. 13. — (1988-89), ‘Two new books by German scholars: Rudiger Fuchs, Das Domesday Book und sein Umfeld. and Jan Gerchow, Die Gedenküberlieferung der Angelsachsen’, Nomina 12, p. 172. — (2003), ‘Society for Name Studies in Britain and Ireland. Twelfth Annual Study Conference: Shetland 2003’, Nomina 26, pp. 119–127. Atkin, M. A. (1988-89), ‘Hollin names in north-west England’, Nomina 12, pp. 77–88. — (1990-91), ‘The medieval exploitation and division of Malham Moor’, Nomina 14, pp. -

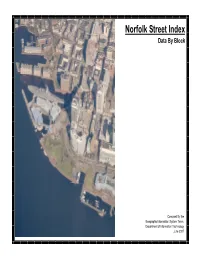

Street Index by Block Range

Norfolk Street Index Data By Block Compiled By the Geographic Information System Team, Department of Information Technology June 2007 Parcel Mapbook Planning Census Page District Tract Street Name Block Range Voting Precinct Ward Superward 10TH BAY STREET 9600-9600 Page 117 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9500-9500 Page 147 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 10TH VIEW STREET 9600-9600 Page 6 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 11TH BAY STREET 9500-9500 Page 147 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9600-9600 Page 117 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9700-9700 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 11TH STREET 100-100 Page 757 58 40.01 EAST 21st STREET / MONTICELLO 2 6 11TH VIEW STREET 9600-9600 Page 5 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 12TH BAY STREET 9500-9500 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9600-9600 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 12TH VIEW STREET 9600-9600 Page 5 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 9700-9700 Page 5 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 13TH BAY STREET 9500-9500 Page 148 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9600-9600 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9700-9700 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 13TH STREET 200-200 Page 758 58 36 EAST 21st STREET / MONTICELLO 2 6 100-100 Page 758 63 36 EAST GHENT 2 6 13TH VIEW STREET 9600-9600 Page 4 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 9700-9700 Page 4 1 4 WILLOUGHBY 1 6 14TH BAY STREET 9500-9500 Page 148 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 9600-9600 Page 118 6 65.01 PRETTY LAKE 5 6 Compiled by the Geographic Information System Team Page 1 of 287 Department of Information Technology June 2007 Parcel Mapbook Planning Census Page District Tract Street Name Block Range Voting Precinct Ward Superward 14TH STREET 100-100 Page 758 58 36 EAST 21st -

Lamarsh Village Hall Magazine Contact Bret & Rosemary Johnson 227988

Look Out The Parish Magazine for Alphamstone, Lamarsh, Great & Little Henny Middleton, Twinstead and Wickham St Pauls May 2020 www.northhinckfordparishes.org.uk WHO TO CONTACT Team Rector: Revd. Margaret H. King [email protected] 269385 mobile - 07989 659073 Usual day off Friday Team Vicar: Revd. Gill Morgan [email protected] 584993 Usual day off Wednesday Team Curate: Revd. Paul Grover [email protected] 269223 Team Administrator: Fiona Slot [email protected] (working hours 9:00 am - 12 noon Monday, Tuesday and Thursday). 278123 Reader: Mr. Graham King 269385 The Church of St Barnabas, Alphamstone Churchwardens: Desmond Bridge 269224 Susan Langan 269482 Magazine Contact: Melinda Varcoe 269570 [email protected] The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Great & Little Henny Churchwarden: Jeremy Milbank 269720 Magazine Contact: Stella Bixley 269317 [email protected] The Church of the Holy Innocents, Lamarsh Churchwarden: Andrew Marsden 227054 Magazine Contact: Bret & Rosemary 227988 [email protected] Johnson The Church of All Saints, Middleton Churchwarden: Sue North 370558 Magazine Contact: Jude Johnson 582559 [email protected] The Church of St John the Evangelist, Twinstead Churchwardens: Elizabeth Flower 269898 Henrietta Drake 269083 Magazine Contact: Cathy Redgrove 269097 [email protected] The Church of All Saints, Wickham St. Pauls Churchwarden: Janice Rudd 269789 Magazine Contact: Susannah Goodbody 269250 [email protected] www.northhinckfordparishes.org.uk Follow us on facebook : www.facebook.com/northhinckfordparishes Magazine Editor: Magazine Advertising: Annie Broderick 01787 269152 Anthony Lyster 0800 0469 069 1 Broad Cottages, Broad Road The Coach House Wickham St Pauls Ashford Lodge Halstead. -

76 Colchester Area from 29 March 2020

Essex 74B 76 Colchester Area from 29 March 2020 Clacton | Colchester 74B via Wivenhoe and Essex University Mondays to Saturdays except Public Holidays Note ECC ECC Service Number 74B 74B Clacton, Pier Avenue 1915 2115 St. Osyth, Red Lion 1930 2130 Thorrington Cross 1938 2138 Wivenhoe, The Flag 1948 2148 Essex University, South Courts 1951 2151 Greenstead Road, Tesco 1957 2157 Colchester, Stanwell Street 2005 2205 Mondays to Saturdays except Public Holidays Note ECC ECC Service Number 74B 74B Colchester, Stanwell Street 2010 2210 Greenstead Road, Tesco 2018 2218 Essex University, South Courts 2024 2224 Wivenhoe, The Flag 2027 2227 Thorrington Cross 2037 2237 St. Osyth, Red Lion 2045 2245 Clacton, Pier Avenue 2100 2300 Notes: ECC Operated under contract to Essex County Council Clacton | Colchester 76 via Weeley and Essex University Sundays and Public Holidays Note ECC ECC ECC ECC ECC ECC ECC Service Number 76 76 76 76 76 76 76 Clacton, Jackson Road 0810 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2010 Great Clacton, The Plough 0817 1017 1217 1417 1617 1817 2017 Little Clacton, Blacksmiths Arms 0823 1023 1223 1423 1623 1823 2023 Weeley, Black Boy 0830 1030 1230 1430 1630 1830 2030 Frating, opp Haggars Lane 0837 1037 1237 1437 1637 1837 2037 Elmstead Market, Budgens 0841 1041 1241 1441 1641 1841 2041 Essex University South Courts 0847 1047 1247 1447 1647 1847 2047 Greenstead Road, Tesco 0853 1053 1253 1453 1653 1853 2053 Colchester, Stanwell Street 0901 1101 1301 1501 1701 1901 2101 Sundays and Public Holidays Note ECC ECC ECC ECC ECC ECC Service Number 76 -

Cultural Sites and Constable Country a HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O

Colchester Town Centre U C E L L O V ST FI K E N IN T R EMPLEW B T ı O R O BO D Cultural sites and Constable Country A HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O S A T E 4 HE A D 3 CA D 1 D D P R A U HA O A E RO N D A RIAG S Z D O MAR E F OO WILSON W EL IE NW R A TO LD ROAD R EWS Y N R OD CH U BLOYES MC H D L R A BRO C D O R A I OA B D R A E LAN N D N D D R S O WA ROA W D MASON WAY T HURNWO O S S Y O I C A Y N P D TW A133 A I R S D A RD E G N E Colchester and Dedham routes W E CO L O R F VENU W A V R A F AY A AL IN B Parson’s COWDR DR N ENT G R LO C IN O Y A133 A DS ES A D A A Y WAY Heath Sheepen VE T A DR G A K C V OR NK TINE WALK 2 E IV K E D E BA N H IS Bridge NE PME IN I N 3 ON D I L A O R N P G R N C S E ER G G U R S O D E G L S 12 N N UM C MEADOW RD E N B H O IG A R R E E A O OA U U E RS E L C L EN A DI S D V R D R L A A A W D D B E D B K T R G D OA A A C I R L N A D R A 1 G B N ST Y T E D T D O R E 3 Y O A O A E O SPORTSWA A N R O L 4 D HE N U REET M W R R IR O V C AR CO EST FA RD R N T M H E D W G I A P S D C A C H R T T Y I V E ON D BA A E T R IL W E S O N O A B R E RO S T D RI W O M R A D R I O E T R N G C HA L I T STO ROAD U W A AU D E M I C UILDFOR R W G D N O A R SHEE C H ASE O BRIS L RO A E N T D PEN A A O S V A R O P OA D E 7 YC RU A D Y 3 W R C N 1 S E O S RD A RC ELL G D T ) A ES W R S TER S LO PAS D R N H S D G W O BY H E GC ENUE ER E U AV EST EP R RO ORY R E I D E K N N L F Colchester P AT N T IC ra L D R U H Remb S D N e ofnce DLEBOROUGH F E Institute ID H O V M ET LB RE E R A C R'SST C R IFER TE E N L E F D H O H ST -

Heritage at Risk Register 2016, East of England

East of England Register 2016 HERITAGE AT RISK 2016 / EAST OF ENGLAND Contents Heritage at Risk III North Norfolk 44 Norwich 49 South Norfolk 50 The Register VII Peterborough, City of (UA) 54 Content and criteria VII Southend-on-Sea (UA) 57 Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Suffolk 58 Reducing the risks XI Babergh 58 Key statistics XIV Forest Heath 59 Publications and guidance XV Mid Suffolk 60 St Edmundsbury 62 Key to the entries XVII Suffolk Coastal 65 Entries on the Register by local planning XIX Waveney 68 authority Suffolk (off) 69 Bedford (UA) 1 Thurrock (UA) 70 Cambridgeshire 2 Cambridge 2 East Cambridgeshire 3 Fenland 5 Huntingdonshire 7 South Cambridgeshire 8 Central Bedfordshire (UA) 13 Essex 15 Braintree 15 Brentwood 16 Chelmsford 17 Colchester 17 Epping Forest 19 Harlow 20 Maldon 21 Tendring 22 Uttlesford 24 Hertfordshire 25 Broxbourne 25 Dacorum 26 East Hertfordshire 26 North Hertfordshire 27 St Albans 29 Three Rivers 30 Watford 30 Welwyn Hatfield 30 Luton (UA) 31 Norfolk 31 Breckland 31 Broadland 36 Great Yarmouth 38 King's Lynn and West Norfolk 40 Norfolk Broads (NP) 44 II East of England Summary 2016 istoric England has again reduced the number of historic assets on the Heritage at Risk Register, with 412 assets removed for positive reasons nationally. We have H seen similar success locally, achieved by offering repair grants, providing advice in respect of other grant streams and of proposals to bring places back into use. We continue to support local authorities in the use of their statutory powers to secure the repair of threatened buildings.