666************11066666666

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cash Box Publishing Co., Inc

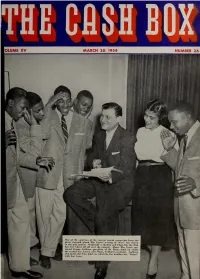

MARCH 20, 1954 : A jpli 1 One of the surprises of the current record season has been the great strength which The Crows’ waxing of “Gee” has shown in the pop market. Originally a rhythm and blues hit, the disk has now taken off all over the country. Above The Crows sur- round George Goldner, president of the Rama label on which the record was issued, and Mona, Goldner’s assistant. Goldner also heads the Tico label on which he has another hit, “Baion” with Joe Loco. The 104-selection Wurlitzer 1500A not only leads the field in its ability to play either 45 or 78 RPM records— it is far out in front in earning power. Now availableqt slight extra cost, with Wurlitzer's extra- ^stimulating Hi-f idelity Sound System, this phono- iph oj^etfSTby far, thelbest investment and the highest ng record in phonograph history. SEE YOUR WSRLITZER DISTRIBUTOR 1500k The Rudolph Wurlitzer Company • North Tonawanda, N. Y. ” The (fash Bine FOUNDED BY BILL GERSH March 1954 20, Music Editorial Vol. XV Number 26 Publishers BILL GERSH JOE ORLECK The Cash Box Publishing Co., Inc. 26 West 47th Street, New York 36, N. Y. (All Phones: JUdson 6-2640) JOE ORLECK • CHICAGO OFFICE 32 West Randolph St., Chicago 1, 111. (All Phones: DEarborn 2-0045) BILL GERSH Karyl Long • LOS ANGELES OFFICE 6363 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, Cal. (Phone: WEbster 1-1121) CARL TAFT • NASHVILLE OFFICE 417 Broadway, Nashville, Tenn. (Phone: NAshville 5-7031) CHARLIE LAMB 200.000. • LONDON OFFICE England 50.000. 17 Hilltop, London, N.W., fourth annual MOA (Music Since it is estimated that approximately MARCEL STELLMAN The • Operators of America) Convention was 000 pop records were sold last EXECUTIVE STAFF JOE ORLECK, Advertising Director a smashing success. -

Eden of the South a Chronology of Huntsville, Alabama 1805-2005

Eden of the South A Chronology of Huntsville, Alabama 1805-2005 Edited by: Ranee' G. Pruitt Eden of the South . begins with the discovery of a limestone spring by settler John Hunt. In just over a century and a half, the settlement named in his honor would make worldwide headlines for research and development, earning Huntsville the name, the Space Capital of the World. But our history did not stop there! This book takes readers back to the little known incidental moments uncovered from numerous sources, as well as the amazing details behind the big events, famous people, and, more importantly, the unsung heroes. Two hundred years, a brief snapshot in time, are remembered by the people of the time. Over 700 photographs capture moments and commit them to immortality. Tragedies and triumphs, thought to be long forgotten, are recorded in one fascinating book. The Huntsville-Madison County Public Library proudly offers this publication as a fitting birthday present to celebrate the first 200 years of Huntsville, Alabama, the Eden of the South. EDEN OF THE SOUTH A Chronology of Huntsville, Alabama 1 8 0 5 - 2 0 0 5 E dited by Ranee G. Pruitt Huntsville-Madison County Public Library Huntsville, Alabama ©2005 Huntsville-Madison County Public Library Huntsville, Alabama 35801 All Rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission of the publisher. Layout design by: James H. Maples Cover artist: Dennis Waldrop Photographer: James Pruitt All photographs, unless otherwise noted, are from the collection of the Huntsville-Madison County Public Library ISBN: 0-9707368-2-7 Published by Huntsville-Madison County Public Library 915 M onroe St. -

Advance Publication Newsletter for Library Managers in Acquisitions and Collection Development BOOKS DUE: JANUARY, FEBRUARY, MARCH, APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 25, NUMBER 1

PENGUIN GROUP (USA) Advance Publication Newsletter For Library Managers in Acquisitions and Collection Development BOOKS DUE: JANUARY, FEBRUARY, MARCH, APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 25, NUMBER 1 “[A] chilling, assured debut….Even the most astute readers will be in for a shock as Hawkins slowly unspools the facts, exposing the harsh realities of love and obsession’s inescapable links to violence.”—Kirkus, starred review “The surprise-packed narratives hurtle toward a stunning climax, horrifying as a train wreck and just as riveting.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review SEE INSIDE FOR MORE TITLES COMING SOON FROM PENGUIN GROUP (USA)! PENGUIN GROUP (USA) 375 HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10014-3657 PHONE (212) 366-2377 • FAX (212) 366-2933 WWW.PENGUIN.COM January 2015 Dear Librarian: Welcome to the Winter 2015 edition of PENGUIN GROUP (USA)’s Advance Publication Newsletter. This newsletter includes late-breaking reviews, news of award-winners, up-to-date price information, and book descriptions for January through April titles. We hope you will take some time to review the new books included here. As usual, the newsletter is divided into subject categories in order to route each section to your appropriate acquisitions and collection development specialists. Some highlights: • The inimitable Stewart O’Nan returns, bringing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s attempt at a second act as a Hollywood screenwriter vividly to life in West of Sunset (see Fiction). Fans of Gone Girl won’t want to miss Paula Hawkins’s Hitchcockian debut thriller The Girl on the Train (see Mysteries/Thrillers), while readers looking for a supernatural page-turner will love Simone St. -

Advanced Manufacturing SPECIAL ISSUE

www.dau.mil | July-August 2016 A PUBLICATION OF THE DEFENSE ACQUISITION UNIVERSITY Advanced Manufacturing SPECIAL ISSUE Manufacturing Learning from the Past Keeping Track Innovation and to Plan for the Future of Horseshoe Nails Technological Restoring Manufacturing for Industrial Base Analysis Superiority National Security and Sustainment by the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics From the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics CONTENTS Manufacturing Innovation and Technological Superiority 2 Frank Kendall 6 10 13 SPECIAL ISSUE: ADVANCED MANUFACTURING Learning From the Past to Plan Keeping Track of Horseshoe Nails Stitching Together the for the Future Industrial Base Analysis and “Digital Thread” Restoring Manufacturing for National Sustainment Jacob Goodwin Security Bradley K. Nelson One institute is charged with expanding A. Adele Ratcliff The central need for an adequate and the field of “digital manufacturing and The Department of Defense establishes reliable supply of critical warfighting mate- design,” or the creative use of data at eight Manufacturing Institutes to promote rials long before the outbreak of hostili- every stage of the manufacturing process emerging technologies and deliver new ties applies to both big-ticket items and to increase efficiency and speed while capabilities to the warfighter. simpler and more generic ones. cutting cost. 16 20 26 Manufacturing Technology Program When America Makes, The Breath of Life Bringing Innovation to the Warfighter -

Eastern Progress 1981-1982 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1981-1982 Eastern Progress 12-10-1981 Eastern Progress - 10 Dec 1981 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1981-82 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 10 Dec 1981" (1981). Eastern Progress 1981-1982. Paper 15. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1981-82/15 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1981-1982 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 60/No. 15 Laboratory Publication ol tht Department ol Maaa Communication! Thursday, 10, 1961 Richmond, Ky. 40475 Three football players arraigned in rape case Three university football players According to a statement released ment but declined further comment were arraigned Wednesday morning by the Richmond police Tuesday, on the arrests. in Madison District Court on they were informed at approxi- Since the preliminary hearing charges of first degree rape. mately 11:23 p.m. Dec. 6 that a 21- was set for late December, the play- Rodney Allen Byrd, 21, of year-old woman had come to the ers will be able to participate in any Brooksville, Fla., David Hill Jr., 19. emergency room at the Pattie A. remaining playoff games. of Miami, and Steven Mike Wagers, Clay Hospital reporting that she 21, of Dade City, Fla., were released had been raped. If sufficient evidence is present to from Madison County Jail following continue the case, it would be early The woman said that at approxi- to mid-January before the rape case arraignment before District Court mately 9:30 p.m. -

The Nebraska Minority and Justice Task Force Final Report

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications of the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center Public Policy Center, University of Nebraska April 2011 The Nebraska Minority and Justice Task Force Final Report Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/publicpolicypublications Part of the Public Policy Commons "The Nebraska Minority and Justice Task Force Final Report" (2011). Publications of the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center. 100. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/publicpolicypublications/100 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Public Policy Center, University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications of the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Nebraska Minority and Justice Task Force Final Report January 2003 SJI State Justice Institute The Nebraska Minority and Justice Task Force Final Report January 2003 The work of this Task Force and the publication of this report was funded in part by a grant (Grant No. SJI-02-N-006) from the State Justice Institute. Points of view expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the State Justice Institute. ii Thomas Jefferson once said that all men are created equal….We know all men are not created equal in the sense some people would have us believe – some people are smarter than others, some people have more opportunity because they are born with it, some men have more money than others…some people are born with gifts beyond the scope of most men. -

Plowing Concrete RTS Alumni Plant Churches in the Spiritually Hard Ground of New England

FALL 2011 www.rts.edu Plowing Concrete RTS alumni plant churches in the spiritually hard ground of New England. Scripture and Science 6 • Dietrich Bonhoeffer Revisited 14 Chancellor’s Message Dr. Robert C. Cannada Jr. e in the RTS fam- pel voices in New England such as Jon- ily have received athan Edwards have become objects of a sacred trust — to irrelevance if not outright ridicule. preach the gospel of However, RTS alumni such as the ones light to those lost in featured in “Plowing Concrete” (see spiritual darkness. This is the same page 8) are among those helping rein- historic gospel with which the Apostle troduce the historic gospel to one of the Paul himself was entrusted (Galatians birthplaces of the American church. In 2:7, 1 Thessalonians 2:4, 1 Timothy so doing, they help us understand that 1:11) and that alone is “the power of while our missional focus takes us to the God for salvation to everyone who be- ends of the earth, some of the places we lieves” (Romans 1:16). reach along the way land closer to home Our commitment to proclaiming than we might imagine. “Re-evangeliz- this good news has been a hallmark of ing” the United States is a formidable RTS from its founding in 1966 to this task requiring significant attention. Chancellor and Chief Executive Officer very day. “Standing firm but not stand- In addition, new fields of spiritual ing still” remains our focus in that we harvest are sprouting up all over the remain anchored to the truth of the globe, whether they are near military Contents gospel even while we actively take that bases in Germany or among the mil- truth to the ends of the earth and to lions of Muslims in Indonesia. -

1969 Quicksilver Times the QUICKSILVER TIMES Is Published by the Washington Editor

Page 2 November 26-December 6, 1969 Quicksilver Times The QUICKSILVER TIMES is published by the Washington Editor: . Independent Publishing Co., My enthusiasm for 1932 17th St., NW, Washing• much of QST, its poli• ton, D.C. 20009. cies, and its style is, Telephone: (202) 483-8000. to say the least re• E strained, but the cen• Published every 10 days. ter-fold piece by Mal• colm Kovacs on the Nat'l Ad Rep - Concert Hall T Three Sisters Bridge controversy deserves Member - Liberation News congratulations. Ko• Servi ce vacs (and QST) gave T depth and perspective Office Hours: 10 to 10 daily to a story that the "professionals" of the E Star and the Post muck• STAFF ed up completely. Whether the establish• Terry Becker ment press failed be• Peggy O'Callaghan R cause of ineptitude or Steve Gray deliberate design I Connie Bales can't say (though both Steve Guss S papers editorially fa• Richard Harrington vor the bridge). Congratulations Gary Chapman to Mr. Kovacs, who sees where it Patti Heck is. Vera Tas 6ETlN1b M. J. Halberstam Sal Torey COLUMNISTS Eugene Schoenfeld, M.D, Dick Gregory Help! CONTRIBUTORS Brothers and Sisters, anyone Monty Neill who was at the Yippie march Malcolm Kovacs on the Injustice Dept. and is Bonnie Packer willing to testify on a witness Sherry Reeder stand about the pigs use of Joe Steele saturation teargassing, please contact Terry Becker at Quick• silver Times. 483-8000. This is urgent. Also needed are PAPERS AVAILABLE: witnesses who can describe the positioning of the pigs Capital Hill Bookshop - 525 Constitution Ave. -

Granholm Tax Plan Draws Fire From

20100215-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 2/12/2010 6:11 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 26, No. 7 FEBRUARY 15 – 21, 2010 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2010 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Page 3 Health of VEBA in question Filings:UAW health plan’s assets may fall short Retirees could lose BY JAY GREENE Motors Co. and Chrysler Group L.L.C. future, retirees could be left without Goodwill creates CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS And because of uncertainty over paid health care services, and hos- services, and the plan’s assets, the UAW is ex- pitals and physicians in Michigan recycling subsidiary Without much fanfare on Jan. 1, pected to make benefit plan could be left with unpaid bills. providers could be left the United Auto Worker’s health plan changes and negotiate lower rates When the UAW’s plan, also for retirees — called the UAW Re- with contracted health plans and known as a Voluntary Employee Ben- with unpaid bills. tiree Medical Benefits Trust — insurers this year. eficiary Association Talk of sale heats up battle , received feder- funding schedule. opened its doors. The changes would be for con- al court approval in 2008, Detroit 3 However, the auto companies over border bridges How long it remains in opera- tracts starting in 2011 and 2012, ac- automakers were supposed to con- and the UAW have since agreed to tion is a question, however. cording to interviews with several tribute about $57 billion. replace some cash contributions Federal filings indicate the contracted health insurers and in- That contribution would have with common stock, lowering the Inside UAW may not have enough assets dustry sources.