Simon Roberts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of Seaside Towns

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities Report of Session 2017–19 The future of seaside towns STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01am Thursday 4 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Ordered to be printed 19 March 2019 and published 4 April 2019 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 320 STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities The Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities was appointed by the House of Lords on 17 May 2018 “to consider the regeneration of seaside towns and communities”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities were: Baroness Bakewell (from 6 September) Lord Mawson Lord Bassam of Brighton (Chairman) Lord Pendry (until 18 July 2018) Lord Grade of Yarmouth Lord Shutt of Greetland Lord Knight of Weymouth Lord Smith of Hindhead The Bishop of Lincoln Baroness Valentine Lord Lucas Baroness Whitaker Lord McNally Baroness Wyld Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. -

Alfatravel.Co.Uk | 01257 248000 Welcome to the ALFA TRAVEL BROCHURE

DEPARTING Your UK FROM holiday choice YORKSHIRE & EAST MIDLANDS Coach& SELF DRIVEHolidays BREAKS November 2020 - December 2021 The UK’s only Employee Owned Travel Company alfatravel.co.uk | 01257 248000 Welcome to the ALFA TRAVEL BROCHURE Hello…… and a warm welcome to our Whether you choose to sit back and take NEW 2021 brochure, featuring a in stunning views from the comfort of your handpicked collection of holidays to the personal, luxury seat on our coach breaks, or WHAT IS EMPLOYEE OWNERSHIP? UK’s finest seaside destinations, with you prefer to experience the freedom to go Our business is majority owned by a trust amazing included excursions and seasonal as you please on our self drive breaks in your operated on behalf of our employees. offers – all designed to make memories own car, you’re always assured of the same This means that each and every one of our that will last a lifetime. great Alfa hospitality. drivers, interchange, hotel and central office teams equally benefit from the success of our As the only employee owned travel Our experience and heritage means we are business. We believe this is what makes the company in the UK, our team of resident truly trusted by our customers who book Alfa Leisureplex difference, with every one of our employee owners dedicated to going that ‘Alfa Travel Memory Makers’ have been with us again and again, and as an employee extra mile to provide you with a memorable busy designing a fantastic new range owned business that’s something that makes holiday experience. of holiday experiences within the UK us all very proud. -

Rails by the Sea.Pdf

1 RAILS BY THE SEA 2 RAILS BY THE SEA In what ways was the development of the seaside miniature railway influenced by the seaside spectacle and individual endeavour from 1900 until the present day? Dr. Marcus George Rooks, BDS (U. Wales). Primary FDSRCS(Eng) MA By Research and Independent Study. University of York Department of History September 2012 3 Abstract Little academic research has been undertaken concerning Seaside Miniature Railways as they fall outside more traditional subjects such as standard gauge and narrow gauge railway history and development. This dissertation is the first academic study on the subject and draws together aspects of miniature railways, fairground and leisure culture. It examines their history from their inception within the newly developing fairground culture of the United States towards the end of the 19th. century and their subsequent establishment and development within the UK. The development of the seaside and fairground spectacular were the catalysts for the establishment of the SMR in the UK. Their development was largely due to two individuals, W. Bassett-Lowke and Henry Greenly who realized their potential and the need to ally them with a suitable site such as the seaside resort. Without their input there is no doubt that SMRs would not have developed as they did. When they withdrew from the culture subsequent development was firmly in the hands of a number of individual entrepreneurs. Although embedded in the fairground culture they were not totally reliant on it which allowed them to flourish within the seaside resort even though the traditional fairground was in decline. -

Simon Robertshas Photographed Every British Pleasure Pier There Is

Simon Roberts has photographed every British pleasure pier there is – and several that there aren’t. Overleaf, Francis Hodgson celebrates this devotion to imperilled treasures 14 15 here are 58 surviving pleasure piers in Britain and Simon Roberts has photographed them all. He has also photographed some of the vanished ones, as you can see from his picture of Shanklin Pier on the Isle of Wight (on page 21), destroyed in the great storm which did so much damage in southern England on October 16, 1987. Roberts is a human geographer by training, and his study of piers is a natural development of his previous major work, We English, which looked at the changing patterns of leisure in a country in which a rising population and decreasing mass employment mean that more of us have more time upon our hands than ever before. We tend to forget that holidays are a relatively new phenomenon, but it was only after the Bank Holiday Act of 1871 that paid leave gradually became the norm, and cheap, easily reachable leisure resorts a necessity. Resorts were commercial propositions, and the pier was often a major investment to draw crowds. Consortia of local businessmen would get together to provide the finance and appoint agents to get the thing Previous page done: a complex chicane of lobbying for private spans English Channel legislation, engineering, and marketing. Around design Eugenius Birch construction Raked the same time, a number of Acts made it possible and vertical cast iron screw to limit liability for shareholders in speculative piles supporting lattice companies. -

Pier Pressure: Best Practice in the Rehabilitation of British Seaside Piers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Pier pressure: Best practice in the rehabilitation of British seaside piers A. Chapman Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK ABSTRACT: Victorian seaside piers are icons of British national identity and a fundamental component of seaside resorts. Nevertheless, these important markers of British heritage are under threat: in the early 20th century nearly 100 piers graced the UK coastline, but almost half have now gone. Piers face an uncertain future: 20% of piers are currently deemed ‘at risk’. Seaside piers are vital to coastal communities in terms of resort identity, heritage, employment, community pride, and tourism. Research into the sustainability of these iconic structures is a matter of urgency. This paper examines best practice in pier regeneration projects that are successful and self-sustaining. The paper draws on four case studies of British seaside piers that have recently undergone, or are currently being, regenerated: Weston Super-Mare Grand pier; Hastings pier; Southport pier; and Penarth pier. This study identifies critical success factors in pier regeneration and examines the socio-economic sustainability of seaside piers. 1 INTRODUCTION This paper focuses on British seaside piers. Seaside pleasure piers are an uniquely British phenomena, being developed from the early 19th century onwards as landing jetties for the holidaymakers arriving at the resorts via paddle steamers. As seaside resorts developed, so too did their piers, transforming by the late 19th century into places for middle-class tourists to promenade, and by the 20th century as hubs of popular entertainment: the pleasure pier. -

14 Newton Road Mumbles Swansea Sa3 4Au

TO LET – GROUND FLOOR RETAIL UNIT 14 NEWTON ROAD MUMBLES SWANSEA SA3 4AU © Crown Copyright 2020. Licence no 100019885. Not to scale geraldeve.com Location Viewing The property is situated in the main retail pitch of Newton Strictly by appointment through sole agents, Gerald Eve LLP. Road in Mumbles. Mumbles is located four miles south west of Swansea city centre and is an affluent district which sees Legal costs many tourists throughout the year due to the nearby beaches and its tourist hotspots such as Mumbles Pier and Oystermouth Each party to bear their own costs in the transaction. Castle. Mumbles is the gateway to the Gower, the first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty to be designated in the UK. VAT The property sits 40m from the junction of Newton Road and The property is exempt from VAT and therefore VAT will not be Mumbles Road, the main arterial route from Swansea city centre payable on rent and service charge payments. to Mumbles. There is a good mix of independent and national retailers along Newton Road including Marks & Spencers, Lloyds, Co-operative Food, WH Smith and Tesco Express. EPC Description The property comprises a ground floor retail unit with glazed frontage and recessed access doors under a canopy that extends along the north side of Newton Road. Internally the unit comprises a generous sales area that is regular in shape, leading to a storage area, an office and WC’s. The property benefits from external storage and additional access at the rear. Floor area Ground floor Sales 552 sq ft Ground Floor Ancillary 76 sq ft External rear store 76 sq ft Contact Tom Cater Tenure [email protected] Available to let on a new lease on terms to be negotiated. -

27Th March 1936

T hl' ·· Elim E,·:ing:<,] :ind Four~quarc R ev i,·ali:--1., ·• :\l;irc li 2;-lh, ]936. REVIVAL BREAKS OUT AT GLASGOW (see page 200) im~~an ' . AND mr.·£ T icT ~- 1lJARE DJ;',,•' "- ·· -~ Vot XVII:, No. 13 MARCH 27th, 1936 Twopence AMONG TH E SWISS MOUNTAINS " H e makcth me to lie down in p:-i~turcs of tender grass."-Psa. xxiii. 2 (Newberry). I will; 1 too. '>-- Ts1BL l ean11." .' / arK' .. 1 - Cover ii. TI-11'.: ELIM EVANGEL AND FOURSQUARE REVIVALIST March 27th, 1936. EASTER MONDAY, APRIL 13th, 1936. The Elim Evangel ELEVENTH ANNUAL FOURSQUARE COSPEL AND FOURSQUARE REVIVALIST (Editor: Pastor E. C. W. Boulton.) Offici~d Org:an of the Elim Foursquare Gospel Allianc•. DEMONSTRATION EXECUTIVE COUNCIL: Principal George Jeffreys (President) in the Pa .. 1ors E. J. Philhps {Secret~ry•General), E. C. W. Boulton, P. N. Curry, R. C:. Darragh, W. G. Hathaway, J. McWhirter, J. Smith & R. Tweed. ROYAL ALBERT HALL (London) General Headquarters, when 20, Clarence Raad, Clapham Park, London, s.w.,. Principal GEORGE JEFFREYS Vol. XVII, March 27, 1936 No, 13 WILL PREACH AT THREE GREAT GATHERINGS 11 a.m. Divine Healing; 3 p.m. Baptismal Service; CONTENTS 7 p.m. Communion Service :\atur:d and Supenrntural Physical Healing 193 RESERVED SEATS. Tickets for seats in the BoxPs and Cuslly ,·ersus Cheap Religious Experiences 195 S1:ills are obtainable at the following prices: Morning, 1/-; :vJusic: Tdurnphant Prnisc 196 Afternoon 2/-; Evening 2/-. Those who purchase these tickets Bible Study Helps 196 ensure a good seat, and at the same time help to reduce the \Vorld Fvents and their Significance 197 rent we pay for the hall. -

Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Annual Conference 2011 a CELEBRATION of MARINE LIFE at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton

Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Annual Conference 2011 A CELEBRATION OF MARINE LIFE at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton 11th - 13th March 2011 www.pmnhs.co.uk PROGRAMME & BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Organizers: Roni Robbins, ARTOO Marine Biology Consultants Tammy Horton, NOC Roger Bamber, ARTOO Marine Biology Consultants 2 Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Annual Conference 2011 A CELEBRATION OF MARINE LIFE at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton Programme Friday 11th March 2011 09.00 Registration 09.45 Welcome and housekeeping 10.00 Paul Tyler – Census of Marine Life: what have we learned from this 10-year programme? 10.45 Bob Kennedy & G. Savidge – Benthic monitoring at Strangford Lough Narrows in relation to the installation of the SeaGen wave turbine. 11.05 Tea/coffee break 11.30 Teresa Darbyshire – The polychaetes of the Isles of Scilly: a new annotated checklist. 11.50 Garnet Hooper-Bué – BioScribe – a new decision support tool for biotope matching. 12.10 Amy Dale – Seagrass in the Solent 12.30 Lunch 13.30 David Barnes, Piotr Kuklinski, Jennifer Jackson, Geoff Keel, Simon Morley & Judith Winston – Scott‟s collections help reveal rapid recent marine life growth in Antarctica. 13.55 Yasmin Guler – The effects of antidepressants on amphipod crustaceans. 14.15 Paula Lightfoot – From dive slate to database: sharing marine records through the National Biodiversity Network. 14.45 Geoff Boxshall – The magnitude of marine biodiversity: towards a quarter of a million species but not enough copepods! 15.15 Tea/coffee break 15.45 Simon Cragg – Prospecting for enzymes with biotechnological potential among marine wood-boring invertebrates. 16.15 Lin Baldock & Paul Kay – Diversity in the appearance of British and Irish gobies. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

THE LIFE-BOAT the Journal of the Royal National Life-Boat Institution

THE LIFE-BOAT The Journal of the Royal National Life-boat Institution VOL. XXXIV SEPTEMBER, 1955 No. 373 THE LIFE-BOAT FLEET 155 Motor Life-boats 1 Harbour Pulling Life-boat LIVES RESCUED from the foundation of the Life-boat Service in 1824 to 30th June, 1955 - - 79,260 Notes of the Quarter H.R.II. THE DrKF. OF lives were rescued. The category to attended a meeting of the Committee which the greatest number of services of Management of the Institution on was rendered was that of motor the 14th of July. 1955. Licutenant- vessels, steamers, motor boats and General Sir Frederick Browning was barges. There were 20 launches to in attendance. The Duke of Pklin- vessels of this kind and 45 lives were burgh is ex-qfficio a member of the rescued. There were 15 launches to Committee of Management as he is fishing boats and 13 to yachts, but as Master of the Honourable Company of many as 20 lives were rescued from Master Mariners. This was the first yachts and only 4 from fishing boats. time he had attended a meeting, There were 6 launches to aircraft, 3 and during his visit to headquarters he to small boats and dinghies and 2 to examined with great thoroughness the people who had been cut off by the drawings of all the types of life-boat tide. Life-boats were launched 3 being built today. Within a week of times to land sick men, and there were attending the meeting the Duke of 3 launches following reports of distress Edinburgh, on a visit to the Scilly signals which led to no result. -

Essex Act 1987

Essex Act 1987 CHAPTER xx LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE Essex Act 1987 CHAPTER xx ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Citation and commencement. 2. Interpretation. 3. Appointed day. PART II LAND AND OPEN SPACE 4. Provision of parking places in parks, etc. PART III HIGHWAYS AND STREETS 5. Awnings over footways. 6. Grass verges, etc. c. xx Essex Act 1987 PART IV PUBLIC HEALTH AND AMENITIES Section 7. Approval of plans to be of no effect after certain interval. 8. Control of brown tail moth. 9. Control of stray dogs. 10. Registered trees. PART V PUBLIC ORDER AND SAFETY 11. Touting, hawking, photographing, etc. 12. Byelaws as to leisure centres. 13. Access for fire brigade. PART VI ESTABLISHMENTS FOR MASSAGE OR SPECIAL TREATMENT 14. Interpretation of Part VI. 15. Licensing of persons to carry on establishments. 16. Grant, renewal and transfer of licences. 17. Byelaws as to establishments. 18. Offences under Part VI. 19. Part VI appeals. 20. Part VI powers of entry, inspection and examination. 21. Savings. PART VII SEASHORE AND BOATS A. Extent of Part VII 22. Extent of Part VII. B. Houseboats, etc. 23. Interpretation and extent of Head B of Part VII. 24. Restriction on houseboats and jetties. 25. Notices of removal, etc., under Head B of Part VII. 26. Sale or disposal of houseboat, jetty, etc. 27. Entry into possession. 28. Right of appeal under Head B of Part VII. 29. Saving for certain authorities, etc. Essex Act 1987 c. xx iii Section C. Miscellaneous provisions 30. Unauthorised structures on seashore. -

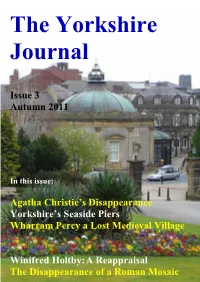

Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Agatha Christie's Disappearance

The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2011 In this issue: Agatha Christie’s Disappearance Yorkshire’s Seaside Piers Wharram Percy a Lost Medieval Village Winifred Holtby: A Reappraisal The Disappearance of a Roman Mosaic Withernsea Pier Entrance Towers Above: All that remain of the Withernsea Pier are the historic entrance towers which were modelled on Conwy Castle. The pier was built in 1877 at a cost £12,000 and was nearly 1,200 feet long. The pier was gradually reduced in length through consecutive impacts by local sea craft, starting with the Saffron in 1880 then the collision by an unnamed ship in 1888. Then following a collision with a Grimsby fishing boat and finally by the ship Henry Parr in 1893. This left the once-grand pier with a mere 50 feet of damaged wood and steel. Town planners decided to remove the final section during sea wall construction in 1903. The Pier Towers have recently been refurbished. In front of the entrance towers is a model of how the pier would have once looked. Left: Steps going down to the sands from the entrance towers. 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Above: Early autumn in the village of Burnsall in the Yorkshire Dales, which is situated on the River Wharfe with a five-arched bridge spanning it Cover: The Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Editorial n this autumn issue we look at some of the things that Yorkshire has lost, have gone missing and disappeared. Over the year the Yorkshire coast from Flamborough Head right down to the Humber estuary I has lost about 30 villages and towns.