Not Welcome Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Leyenda De Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 Pie Izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney Siempre Fue Un Talento Incontro- Enero

JUGADORES GOLES 53de cabeza11 ROONEY, CON MÁS PARTIDOS Ganados 1970-90 PARTIDOS 119 1º Peter Shilton125 71 Empatados 5 2003-17 29 la leyenda de Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 pie izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney siempre fue un talento incontro- enero. "Se merece estar en los libros de 3º David Beckham pie derecho Probablemente, Rooney 115 lable. Su expulsión en los cuartos del historia del club. Estoy seguro de que ROONEY está entre los 10 mejores futbolistas Mundial de 2006 ante Portugal por su anotará muchos más", armó Sir Alex ingleses de la historia. Su carrera es trifulca con Cristiano aún retumba en las Ferguson, el técnico que le llevó al 4º Steve Gerrard2000-14 maravillosa. Islas. Jugó tres Copas del Mundo (2006, United. 114 2010 y 2014) y tres Euros (2004, 2012 y Después de ganar 14 títulos en Old Gary Lineker 2016) sin suerte. Siete goles en 21 Traord, 'Wazza' ha vuelto 13 años partidos de fases nales, 37 en 74 después a casa, al Everton, para apurar 5º Bobby Moore1962-73 Del 12 de febrero de 2003, cuando debutó encuentros ociales y 16 en 45 amistosos su carrera. Y en Goodison Park ha 108 con Inglaterra en un amistoso ante son el baje del jugador de campo con aumentado su mito anotando dos tantos Australia con 17 años y 111 días, a su más duelos y más victorias (71) de la en dos jornadas de liga inglesa que le último duelo, el 11 de noviembre de 2016 historia de Inglaterra al que han llegado disparan a los 200 goles en Premier. -

16Crewealexandraweb26121920

3 Like the way 13 2019 in review promotion feels? A brief round-up of a monumental year in Salford City’s history... HONOURS Eccles & District League Division 2 1955-56, 1959-60 Eccles & District League Division 3 1958-59 Manchester League Division 1 1968-69 Manchester League Premier Division 1974-75, 1975-76, 1976-77, 1978-79 Northern Premier League Division 1 North 2014-15 Northern Premier League Play-Off Winners 2015-16 National League North 2017-18 National League Play-Off Winners 2018-19 Lancashire FA Amateur Cup 1971, 1973, 1975 Manchester FA Challenge Trophy 1975, 1976 Manchester FA Intermediate Cup 1977, 1979 NWCFL Challenge Cup Take your business to the next level with our 2006 award-winning employee wellbeing services CLUB ROLL President Dave Russell Chairman Karen Baird 16. Salford City vs Crewe Alexandra Secretary Andy Giblin Committee Jim Birtwistle, Pete Byram, Ged Carter, Barbara Gaskill, Terry Gaskill, Ian Malone, Frank McCauley, Paul Raven, 07 32 Counselling Advice Online support George Russell, Bill Taylor, Alan Tomlinson, Dave Wilson Groundsmen George Russell, Steve Thomson On The Road The Gaffer Shop Manager Tony Sheldon CSR Co-ordinator Andrew Gordon In this special, Frank McCauley casts Graham Alexander leaves us with his Media Zarah Connolly, Ryan Deane, his mind back over how away trips final notes of the year. Will Moorcroft Photography Charlotte Tattersall, have changed since 2010. Howard Harrison 42 First Team Manager Graham Alexander 25 Assistant Manager Chris Lucketti Visitors Speak to one of our experts today GK Coach Carlo Nash Kit Manager Paul Rushton On This Day Head of Performance Dave Rhodes Find out more about this afternoon’s Physiotherapist Steve Jordan Boxing Day is a constant fixture in the opponents Crewe Alexandra! Club Doctor Dr. -

Phone-Tapping Revelations Shock Mijas Mayor and Council

FREE COPY BREXIT THE NEWSPAPER FOR SOUTHERN SPAIN Costa Brits join Spaniards for Official market leader Audited by PGD/OJD London march March 29th to April 4th 2019 www.surinenglish.com As the UK’s exit from the EU remains unclear, News 2 Health & Beauty 42 Comment 20 Sport 48 residents support calls Lifestyle 22 My Home 53 What To Do 34 Classified 56 for a people’s vote P18 in English Food & Drink 39 Time Out 62 The historic Willow steamboat partially sank Coín has dumped in Benalmádena marina this week due to the enough sewage to rough sea. :: SUR fill a reservoir, says investigation The inquiry into the disposal of polluted water in Nerja and Coín throws up eye-watering figures P6 A third of colon cancer deaths could have been prevented. Residents are urged to take up health service’s screening offer P46 Under the spell of San Miguel de Allende. Andrew Forbes travels to Mexico for this month’s Travel Special P22-25 SPORT Malaga return to league THE COAST FALLS VICTIM TO THE WAVES action tonight after a 1-0 victory over Nàstic brought smiles back to the fans’ Beaches have been battered just two weeks before tourists flock in for Easter P2&3 faces at the weekend P48&49 Phone-tapping revelations shock Mijas mayor and council :: AGENCIA LOF Events in the minority Ciudadanos count, after the director of the coun- It’s not yet known who is council of Mijas took a surprising cil-owned broadcaster was removed, turn this week when it emerged that recently raised the alarm. -

Falcao-Less Monaco Bid to Put Pressure on Paris Saint-Germain

NBA | Page 6 GOLF| Page 7 LeBron Eight-birdie James in Smith upstages doubt for quality fi eld at Cavs opener CIMB Classic Friday, October 13, 2017 FOOTBALL Muharram 23, 1439 AH Mourinho’s GULF TIMES United set for biggest test yet SPORT Page 3 TENNIS SPOTLIGHT Nadal, Federer on Stokes dropped collision course by sponsor AFP ‘I played a very good match, I don’t know how many mistakes I made, but very few’ London AFP Shanghai ngland cricketer Ben Stokes has lost his spon- sorship contract with afael Nadal and Roger Federer sportswear giant New breezed into the quarter-fi nals EBalance following his arrest out- of the Shanghai Masters on side a nightclub which also left Thursday and Juan Martin del his Ashes series in doubt. PotroR defeated racquet-smashing Alex- Stokes, who was arrested on ander Zverev. suspicion of causing actual bod- World number one Nadal blew away ily harm, also issued an apology Fabio Fognini in 63 minutes and plays after video emerged of him mim- sixth seed Grigor Dimitrov as he pur- icking the disabled son of British sues one of the few tournaments to have celebrity Katie Price. eluded him. American fi rm New Balance Timeless rival Federer was even faster, said it “does not condone” be- dismissing Ukrainian qualifi er Alexandr haviour by Stokes, who is also Dolgopolov 6-4, 6-2 in 61 minutes. believed to be the subject of a The 31-year-old Spaniard Nadal, fresh damning video showing a man off the back of triumphs at the US Open throwing multiple punches out- and China Open, anticipates a tough en- side the Bristol nightspot. -

Case Study Football Hero Wins Fans for Pepsi

Case Study Football Hero wins fans for Pepsi PepsiCo International wanted to build on the success of its PepsiMax Club campaign. The goal was to attract male consumers aged 18-34 from new markets to its interactive digital football experience to expose them to the PepsiMax brand. Building a Social Gaming Solution Building on the momentum of the 2010 World Cup, Microsoft® Advertising and PepsiCo developed Football Hero, an innovative web experience that set the stage for football fans around the world to dive into the action and feel like a world-famous footballer. The Microsoft Advertising Global Creative Solutions team worked closely with PepsiCo International Digital Marketing and OMD International to design, build, and deploy the campaign. Microsoft Advertising promoted Client PepsiCo International the campaign in 14 global markets via editorial and media Countries UK, Spain, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Brazil, Mexico, properties such as Xbox.com, Xbox LIVE®, Hotmail®, and Romania, Greece, Poland, Argentina, Egypt, Saudi the MSN Portal. Arabia, and Ireland One key to the success of Football Hero was making the Industry CPG microsite relevant to local gamers in the 14 target Agencies OMD countries. Microsoft Advertising developed 30 versions of the microsite in 10 languages to allow PepsiCo to Objectives Engage target audience with an interactive, immersive, and fun experience showcase the individual promotions and advertising messages specifically crafted for each local market. The Target end result: A centrally controlled web experience with Audience Males 18-34 local flavor. Solutions Custom microsite, MSN, Windows Live, Xbox LIVE Results 10 million unique users One million games shared virally 10 minutes on site and games per user (average) Going from Zero to Hero The Football Hero experience offered five interactive games and featured exclusive content from international football stars such as Lionel Messi, Didier Drogba, Thierry Henry, Kaka, Frank Lampard, Fernando Torres, Andrei Arshavin, and Michael Ballack. -

Rebuilding Efforts to Take Years News Officials Estimate All Schools in Oslo Were Evacu- Ated Oct

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY News In Your Neighborhood A Midwest Celebrating 25 welcome Se opp for dem som bare vil years of Leif leve sitt liv i fred. to the U.S. De skyr intet middel. Erikson Hall Read more on page 3 – Claes Andersson Read more on page 13 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 122 No. 38 October 21, 2011 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com Rebuilding efforts to take years News Officials estimate All schools in Oslo were evacu- ated Oct. 12 closed due to it could take five danger of explosion in school years and NOK 6 fire extinguishers. “There has been a manufacturing defect billion to rebuild discovered in a series of fire extinguishers used in schools government in Oslo. As far as I know there buildings have not been any accidents be- cause of this,” says Ron Skaug at the Fire and Rescue Service KELSEY LARSON in Oslo. Schools in Oslo were Copy Editor either closed or had revised schedules the following day. (blog.norway.com/category/ Government officials estimate news) that it may take five years and cost NOK 6 billion (approximately Culture USD 1 billion) to rebuild the gov- American rapper Snoop Dogg ernment buildings destroyed in the was held at the Norwegian bor- aftermath of the July 22 terrorist der for having “too much cash.” attacks in Oslo. He was headed to an autograph Rigmor Aasrud, a member of signing at an Adidas store on the Labor Party and Minister of Oct. -

A Football Journal by Football Radar Analysts

FFoooottbbaallll RRAADDAARR RROOLLIIGGAANN JJOOUURRNNAALL IISSSSUUEE FFOOUURR a football journal BY football radar analysts X Contents GENERATION 2019: YOUNG PLAYERS 07 Football Radar Analysts profile rising stars from around the globe they tip to make it big in 2019. the visionary of nice 64 New ownership at OGC Nice has resulted in the loss of visionary President Jean-Pierre Rivere. Huddersfield: a new direction 68 Huddersfield Town made the bold decision to close their academy, could it be a good idea? koncept, Kompetenz & kapital 34 Stepping in as Leipzig coach once more, Ralf Rangnick's modern approach again gets results. stabaek's golden generation 20 Struggling Stabaek's heavy focus on youth reaps rewards in Norway's Eliteserien. bruno and gedson 60 FR's Portuguese analysts look at two players named Fernandes making waves in Liga Nos. j.league team of the season 24 The 2018 season proved as unpredictable as ever but which players stood out? Skov: THE DANISH SNIPER 38 A meticulous appraisal of Danish winger Robert Skov's dismantling of the Superligaen. europe's finishing school 43 Belgium's Pro League has a reputation for producing world class talent, who's next? AARON WAN-BISSAKA 50 The Crystal Palace full back is a talented young footballer with an old fashioned attitude. 21 under 21 in ligue 1 74 21 young players to keep an eye on in a league ideally set up for developing youth. milan's next great striker? 54 Milan have a history of legendary forwards, can Patrick Cutrone become one of them? NICOLO BARELLA: ONE TO WATCH 56 Cagliari's midfielder has become crucial for both club and country. -

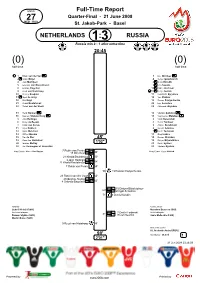

Full-Time Report NETHERLANDS RUSSIA

Match Full-Time Report 27 Quarter-Final - 21 June 2008 NED - RUS St. Jakob-Park - Basel NETHERLANDS: RUSSIA Russia win 3 - 1 after extra-time 20:45 (0) (0) half time half time 1 Edwin van der Sar 1 Igor Akinfeev 2 André Ooijer 4 Sergei Ignashevich 4 Joris Mathijsen 8 Denis Kolodin 5 Giovanni van Bronckhorst 9 Ivan Saenko 8 Orlando Engelaar 10 Andrei Arshavin 9 Ruud van Nistelrooy 11 Sergei Semak 10 Wesley Sneijder 17 Konstantin Zyryanov 17 Nigel de Jong 18 Yuri Zhirkov 18 Dirk Kuyt 19 Roman Pavlyuchenko 21 Khalid Boulahrouz 20 Igor Semshov 23 Rafael van der Vaart 22 Aleksandr Anyukov 13 Henk Timmer 12 Vladimir Gabulov 16 Maarten Stekelenburg 16 Vyacheslav Malafeev 3 John Heitinga 2 Vasili Berezutski 6 Demy de Zeeuw 3 Renat Yanbaev 7 Robin van Persie 5 Aleksei Berezutski 11 Arjen Robben 6 Roman Adamov 12 Mario Melchiot 7 Dmitri Torbinski 14 Wilfred Bouma 13 Oleg Ivanov 15 Tim de Cler 45' 14 Roman Shirokov 19 Klaas Jan Huntelaar 1'02" 15 Diniyar Bilyaletdinov 20 Ibrahim Afellay 21 Dmitri Sychev 22 Jan Vennegoor of Hesselink 23 Vladimir Bystrov Head Coach: Marco Van Basten 7 Robin van Persie in Head Coach: Guus Hiddink 18 Dirk Kuyt out 46' 21 Khalid Boulahrouz 50' 3 John Heitinga in 21 Khalid Boulahrouz out 54' 7 Robin van Persie 55' 56' 19 Roman Pavlyuchenko 23 Rafael van der Vaart 60' 20 Ibrahim Afellay in 8 Orlando Engelaar out 62' in 15 Diniyar Bilyaletdinov 69' out 20 Igor Semshov 71' 8 Denis Kolodin Referee: Fourth official: Ľuboš Michĕl (SVK) Massimo Busacca (SUI) Assistant referees: in 7 Dmitri Torbinski UEFA delegate: Roman Slyško (SVK) 81' out 9 Ivan Saenko Janis Mežeckis (LVA) Martin Balko (SVK) 9 Ruud van Nistelrooy 86' Man of the match: 10, Arshavin Andrei (RUS) 90' Attendance: 38,374 1 2'01" 21 Jun 2008 23:26:09 Powered by euro2008.com Printed by Match Full-Time Report 27 Quarter-Final - 21 June 2008 NED - RUS St. -

Újonc Az Eb-Torna Fináléjában

Kedd, 2000. február 22. 5 EURO 2000 Norvégia (C-csoport) Újonc az Eb-torna fináléjában A norvég válogatott azon kevés Az utánpótlás-nevelõ programjuk- együttesek közé tartozik, amelynek nak köszönhetõen a 90-es évek má- most sikerült elõször bejutnia egy Eu- sodik felében több jó képességû csatárt rópa-bajnoki torna döntõjébe. is sikerült kinevelniük. A selejtezõk al- Az azt megelõzõ selejtezõk mind- kalmával az új nevelésnek számító já- egyikén részt vettek, de egyszer sem tékosok szerezték a legtöbb gólt: Ole sikerült továbbjutniuk. Gunnar Solskjær - 5, Tore Andre Flo - A norvég futball a kilencvenes évek 5, Steffen Iversen - 4. elején kezdett fejlõdni, az azt megelõzõ Ahogy az a többi skandináv ország- évtizedek futballpolitikája következté- ra is jellemzõ, a norvég válogatott a ben. Ugyanis a szomszédos országok külföldön játszó sztárjaira épít. Az õ mintájára Norvégiában is elkezdõdött tudásukat és nemzetközi tapasztalatu- egy nagyszabású utánpótlás-nevelõ kat kiválóan egészítik ki a Champions program, olyan központokkal, mint League-ba lassan már bérletet váltó Oslo (Valerenga Fotball), Trondheim Rosenborg Trondheim csapatának já- (Rosenborg), Bodö (Glimt), Molde tékosai, mint Bergdölmo, Hoftun, Kerettagok (Molde FK) stb. Bragstad, Strand, Carew, Sörensen stb. Név: Született: Csapata: Poszt: Több évi eredménytelenség után a Tore Andre Flo, az FC Chelsea csa- A piros-fehér-kék vagy tiszta fehér- patának egyik kiválósága a selejtezõk Frode OLSEN 1967. október 12. Stabæk m vikingek leszármazottai az északi or- ben szereplõ norvégok rendszerint 1- m alatt a norvégok 21 góljából ötöt szerzett Per E. BAARDSEN 1977. december 7. Tottenham szágok elsõszámú játékosexportálójává 4-4-2-es felállásban játszanak, de volt Andre BERGDØLMO 1971. október 13. -

Date: 3 March 2012 Opposition: Arsenal Competition

Date: 3 March 2012 Times Echo Telegraph Observer Sunday Telegraph March2012 3 Opposition: Arsenal Standard Independent Guardian Sunday Times Mirror Sun Independent Sunday Mail Sunday Mirror Competition: League Van Persie working on a different plane Wenger hopes Van Persie can make impossible possible against Milan Liverpool 1 Liverpool (1) 1 Koscielny 23 (og) Koscielny 23og Arsenal 2 Arsenal (1) 2 Van Persie 31, 90+2 Van Persie 31 90 Referee: M Halsey Attendance: 44,922 Referee Mark Halsey Amid the avalanche of statistics that rained down on Robin van Persie after goals Attendance 44,922 number 30 and 31 of a stellar season had enhanced Arsenal's prospects of Not content with producing one Kodak moment to win the game, Robin van Champions League football and damaged Liverpool's, there was one, more than Persie re-emerged from the players' tunnel almost an hour later to take any other, that told of a striker at the peak of his powers. photographs of an empty and eerily silent Anfield. Arsenal can only pray their It revealed that in the last four matches that the forward has scored, no brilliant Dutchman wanted to record the day of his first goals goalkeeper has saved one of his shots on target, with seven shots yielding seven against Liverpool and not historic English stadiums he may soon leave behind. goals. It reflected Van Persie's stature in a season of 31 goals that he should have a Maximum efficiency is being achieved. Just as gymnasts once aimed for a perfect major influence on the Champions League aspirations of two clubs on Saturday - ten and fencers look to avoid quite literally being foiled, so goalscorers dream of pushing Arsenal closer to a 15th consecutive campaign among the European elite becoming so unerringly accurate in their finishing that goalkeepers are taken out and Liverpool away from their main target for a third year. -

Jeff's History Project

Jeff's History Project Liverpool then and now My Liverpool Project • My name is Jeffrey Thomas Harrop • I have been living in Liverpool for 49 Years • I support Liverpool FC. I watch every home game on dvd and away game • I was born in Liverpool and raised in Hunts Cross as a child • My project is to explain how good my work is and I work very Hard • My project is about the years I have lived in Liverpool Where I have lived in Liverpool • I used to live in 55 Hill foot Avenue with my mum and dad • I spend my childhood at home • I was born in may 3rd 1963 • My dad worked in Standard Triumph • My mum worked in mpte in Hatton Garden • I don’t remember my 1st Birthday 1964 Where I went to school • I went to Otterspool school for boys in 1975. I was in the Juniors where I learned sums and law and woodwork • I left Otterspool school and I joined Holt Hall and I left there to join Riversdale College to do a car care course • I went to Greenways school with John Rand Carl Riley and Leanne Darby Where I like to go in Liverpool • Town • Bootle - The Strand • Speke • The Royal British Legion • West Darby Road shops • The Black-E My Favourite Buildings • The Palm House • The Liverpool Waterfront • St George’s Hall • The Cavern • The Royal Liver • Sefton Park • Albert Dock • The Anglican Cathedral • Echo Arena What I am interested in • The Bay City Rollers • The Incredible Hulk tv series • Crossroads • Emmerdale – Plane crash of 1993 • Kight Rider • Coronation Street THE Incredible HULK • Dr David Banner was played by the late Bill Bixby he died of prosate cancer in 1993 • The Hulk was played the muscle man Lou Ferrigno and this was his first gig • Jack McGee was played by Jack Colvin. -

1987-04-05 Liverpool

ARSENAL vLIVERPOOL thearsenalhistory.com SUNDAY 5th APRIL 1987 KICK OFF 3. 5pm OFFICIAL SOUVENIR "'~ £1 ~i\.c'.·'A': ·ttlewcrrJs ~ CHALLENGE• CUP P.O. CARTER, C.B.E. SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. R.H.G. KELLY, F.C.l.S. President, The Football League President, The Littlewoods Organisation Secretary, The Football League 1.30 p.m. SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND (Under the Direction of Bandmaster D. A. Rogers. BEM) 2.15 p.m. LITTLEWOODS JUNIOR CHALLENGE Exhibition 6-A-Side Match organised by the National Association of Boys' Clubs featuring the Finalists of the Littlewoods Junior Challenge Cup 2.45 p.m. FURTHER SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND 3.05 p.m. PRESENTATION OF THE TEAMS TO SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. President, The Littlewoods Organisation NATIONAL ANTHEM 3.15 p.m. KICK-OFF 4.00 p.m. HALF TIME Marching Display by the Bristol Unicorns Youth Band 4.55 p.m. END OF MATCH PRESENTATION OF THE LITTLEWOODS CHALLENGE CUP BY SIR JOHN MOORES Commemorative Covers The official commemorative cover for this afternoon's Littlewoods Challenge Cup match Arsenal v Liverpool £1.50 including post and packaging Wembley offers these superbly designed covers for most major matches played at the Stadium and thearsenalhistory.com has a selection of covers from previous League, Cup and International games available on request. For just £1.50 per year, Wembley will keep you up to date on new issues and back numbers, plus occasional bargain packs. MIDDLE TAR As defined by H.M. Government PLEASE SEND FOR DETAILS to : Mail Order Department, Wembley Stadium Ltd, Wembley, Warning: SMOKING CAN CAUSE HEART DISEASE Middlesex HA9 ODW Health Departments' Chief Medical Officers Front Cover Design by: CREATIVE SERVICES, HATFIELD 3 ltlewcms ARSENAL F .C.