Contextual Batting and Bowling in Limited Overs Cricket

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P26 Layout 1

26 Sports Thursday, June 27, 2019 Chris Gayle says he is among West Indies greats Always cherish two decades playing for the West Indies: Gayle MANCHESTER: Chris Gayle says he deserves to be West Indies host India for two Tests, three ODIs considered alongside the greats of West Indies cricket and three Twenty20 internationals in August and but is refusing to set a definite date for his retirement. September and Gayle believes that might be the time The swashbuckling opener is still hoping the West to bow out. “Maybe a Test match against India and Indies can sneak into the World Cup semi-finals, with definitely play the ODIs against India. I won’t play the India next in line at Old Trafford today, but the odds T20s. That’s my plan after the World Cup,” said a smil- are stacked heavily against them. ing Gayle, who last played Test cricket in 2014. Jason Holder’s team began the tournament with a Gayle, who has amassed more than 10,000 runs in comprehensive seven-wicket win against Pakistan but ODIs, admitted winning the World Cup would have soon lost momentum and that remains their only victo- been the ideal end to his career. Barring a freak set of ry in six matches. Self-styled “Universe Boss” Gayle, results, the two-time champions, who have three who hit 87 in his team’s heartbreaking five-run loss to games left, will be heading home before the semi- New Zealand on Saturday, said he would always cher- finals. ish his two decades playing for the West Indies. -

Page10sportfgs.Qxd (Page 1)

MONDAY, MAY 3, 2021 (PAGE 10) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Buttler blitzkrieg powers Royals Webinar on 'Teaching of Guru Tegh Bahadur' organised to 55-run victory over SRH Excelsior Correspondent temporary times when the world is NEW DELHI, May 2: Chris Morris (3/29) and ous Jonny Bairstow (30) and Vijay grappling with the pandemic as Mustafizur Rahman (3/20) did the Shankar (8) soon followed. JAMMU, May 2: Department they fortify our faith in human Jos Buttler announced his bulk of the work with the ball With the pressure mounting, of Dean Students Welfare of nature and their problems. return to form with belligerent while Kartik Tyagi (1/32) Rahul skipper Kane Williamson (20) Cluster University of Jammu today The programme commenced maiden T20 hundred as Rajasthan Twetia (1/45) picked a wicket went for the big shot only to be organised webinar on the life and with a prayer video imploring for Royals made a mincemeat of an apiece. caught at deep midwicket by teachings of Guru Tegh Bahadur, hope and cure of millions of fellow out-of-sorts Sun Risers Hyderabad, With the win, the Royals Morris off Tyagi as wickets tum- the 9th Guru of Sikh community. Indians falling prey to the deadly winning Sunday's IPL encounter moved up to fifth spot while SRH bled at regular intervals. The webinar was organised as pandemic, followed by a one by a whopping 55-run margin. continued to stay at the bottom, Mohammad Nabi (17 off 5) part of Azaadi Ka Amrut Mahotsav. minute silence to pay homage to all Opening the innings, Buttler having won only one match all sea- injected some hope in the SRH The objective of the lecture was to the departed souls who fell victim smashed a breathtaking 124 off 64 son. -

Indian Premier League 2019

VVS LAXMAN Published 3.4.19 The last ten days have reiterated just how significant a place the Indian Premier League has carved for itself on the cricke�ng landscape. Spectacular ac�on and stunning performances have brought the tournament to life right from the beginning, and I expect the next six weeks to be no less gripping. From our point of view, I am delighted at how well Hyderabad have bounced back from defeat in our opening match, against Kolkata. Even in that game, we were in control �ll the end of the 17th over of the chase, but Andre Russell took it away from us with brilliant ball-striking. Even though I was in the opposi�on dugout, I couldn’t help but marvel at how he snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. The beauty of our franchise is that the shoulders never droop, the heads never drop. There is too much experience, quality and class among the playing group for that to happen. As members of the support staff, our endeavour is to keep the players in a good mental space. But eventually, it is the players who have to deliver on the park, and that’s what they have done in the last two games. David Warner has been outstanding. There is li�le sign that he has been out of interna�onal cricket for a year. His work ethics are exemplary, and I can see the hunger and desire in his eyes. He is striking the ball as beau�fully as ever, and there is a calmness about him that is infec�ous. -

Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences

James Anderson of England celebrates taking the wicket of Azhar Ali of Pakistan and his 600th Test Match Wicket as Joe Root and Jos Buttler celebrate during Day Five of the 3rd #RaiseTheBat Test Match between England and Pakistan at the Ageas Bowl on Aug 25, 2020 19:33 BST Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences Please find England’s virtual media conferences with Test captain Joe Root and James Anderson following the #raisethebat third Test versus Pakistan at the Ageas Bowl, which ended in a draw. England have won the series 1-0. You will find the following files: -Video and audio file of Joe Root and James Anderson’s media conferences – DOWNLOAD HERE Please credit - England and Wales Cricket Board. England Test Squad: Joe Root (Yorkshire) Captain, James Anderson (Lancashire), Jofra Archer (Sussex), Dominic Bess (Somerset), Stuart Broad (Nottinghamshire), Rory Burns (Surrey), Jos Buttler (Lancashire), Zak Crawley (Kent), Sam Curran (Surrey), Ollie Pope (Surrey), Ollie Robinson (Sussex), Dom Sibley (Warwickshire), Chris Woakes (Warwickshire), Mark Wood (Durham). Ends #raisethebat Three-match Test Series: 1st Test: England v Pakistan, 5-9 August, Emirates Old Trafford, Manchester (England win by three wickets) 2nd Test: England v Pakistan, 13-17 August, Ageas Bowl, Southampton (Match drawn) 3rd Test: England v Pakistan, 21-25 August, Ageas Bowl, Southampton (Match drawn) ____ You'll find all ECB Media Releases and associated resources on our Newsroom > Contacts Danny Reuben Press Contact Head of Team Communications England Men's team [email protected] +44 (0)7825 723 620. -

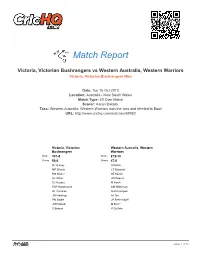

Match Report

Match Report Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers vs Western Australia, Western Warriors Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers Won Date: Tue 15 Oct 2013 Location: Australia - New South Wales Match Type: 50 Over Match Scorer: Aaron Bakota. Toss: Western Australia, Western Warriors won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/69082 Victoria, Victorian Western Australia, Western Bushrangers Warriors Score 331-8 Score 272-10 Overs 50.0 Overs 47.0 RJ Quiney S Katich MP Stoinis CT Bancroft MS Wade* SE Marsh CL White JW Rogers DJ Hussey M North PSP Handscomb SM Whiteman DT Christian N Rimmington JW Hastings AJ Tye PM Siddle JP Behrendorff JM Holland M Beer* S Boland R Duffield page 1 of 36 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers R B 4's 6's SR RJ Quiney . 4 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 2 4 . 1 . 1 1 . 4 . 2 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . // c AJ Tye b AJ Tye 37 37 6 0 100.0 MP Stoinis . 4 . 4 2 . 1 . 1 . 2 1 1 . 1 . run out (CT Bancroft) 63 92 5 2 68.48 2 . 1 . 4 6 . 4 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 1 6 . 1 1 . 1 . 5 1 2 1 1 1 1 . // MS Wade* . 4 . 4 . 1 . 1 . 4 2 . 1 1 1 4 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 1 1 4 . 1 lbw b M Beer* 74 82 9 1 90.24 . 1 1 2 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 4 . 1 1 1 . 6 1 1 4 1 1 1 . 2 . // CL White . 4 . 1 . -

Ashwin Spoils Jennings Debut Ton with Three-Wicket Burst

Sports FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2016 Pak has poor 1st day on Aust tour CAIRNS: Pakistan’s cricket tour of Australia got off to a shaky start yesterday when the visitors were all out for 208 on the first day of a three-day tour match against a Cricket Australia XI. Playing with a near full-strength lineup and with a pink ball in the day-night match in preparation for the first test on Dec. 15 in Brisbane - also a day-night encounter - Pakistan lost six wickets in the final session under lights. Cricket Australia XI bowler Cameron Valente claimed four wickets, including three of Pakistan’s top six. After winning the toss and electing to bat, the visitors fell to 50-3 midway through the opening session, and wickets went down steadily from there. Only veteran Younis Khan offered sustained resistance, facing 138 balls before he inside-edged a ball from Ryan Lees that swung back slightly under lights to be caught behind for 54. He was the only Pakistan batsman to reach 50. Earlier yesterday, Pakistan officials said uncapped 17-year-old left-arm spinner Mohammad Asghar would join the team as a backup for injured legspinner Yasir Shah. Shah is doubtful for the first test following a back injury which also ruled him out of the Cairns match. Asghar has taken 68 wickets in 17 first-class matches since making his debut in 2014. Shah had been pivotal to Pakistan’s suc- cess in test matches for the last two years, taking 116 wickets in only 20 tests. -

Mental Strength Triumphs in Nail- Biting Finals Heroes: Ben Stokes (Left) and Novak Djokovic (Right) Triumphed in Tense Matches on Sunday

Mental strength triumphs in nail- biting finals Heroes: Ben Stokes (left) and Novak Djokovic (right) triumphed in tense matches on Sunday. Are mental powers in sport more exciting than physical skills? Cricketer Ben Stokes and Wimbledon champion Novak Djokovic performed under crushing pressure to seize victories on Sunday. Sunday 14 July, 7pm. At Lord’s Cricket Ground in north London, the Cricket World Cup final is — unbelievably — tied. England and New Zealand must battle it out in the first-eversuper over in the sport’s history. England batsman Ben Stokes has pulled his team back from the brink of defeat. He is exhausted, physically and emotionally, but the expectations of a nation rest on his shoulders. The pressure is on. He has just six balls to score enough runs to secure England’s first- ever cricket World Cup title. Meanwhile, on the other side of London, at Wimbledon’s Centre Court, the longest men’s tennis final in the history of the tournament goes to a fifth set tie-break. At last, Novak Djokovic has three championship points to close out this epic battle. But the crowd is cheering the name of his opponent, Roger Federer. Both men prevail under immense psychological pressure. Later, Djokovic admits the match was the most “mentally demanding” of his career. “For me, at least, it’s a constant battle within, more than what happens outside,” he said. The Serbian player is known to practise meditation and yoga to reach a state of calm. These mental tricks helped him play his best tennis for almost five hours, despite the majority of the 15,000 crowd backing Federer. -

Page-10 Rahul.Qxd

10 z Wednesday z April 28, 2021 De Villiers delivers again as RCB pip DC by one run Shubham’s brilliant 294 runs lead the Capitals managing 43/2 in Avesh Khan (1/24) -- who all tions. the first six overs. picked one wicket apiece, put Put in to bat, Devdutt SK Green to emphatic victory As boundaries dried up, Pant up a collective effort to restrict Padikkal (17) and skipper and new-batsman Marcus RCB. Virat Kohli (12) were off to a Stoinis (22) kept the score- De Villiers, who hit three flying start, amassing 30 runs board ticking by taking singles fours and five sixes, was the top in 3.5 overs. and doubles on offer. scorer for RCB. Pacer Avesh provided the With the required run rate The veteran South African Capitals with the first break- increasing both batsmen hit 22 runs off the last over through, dismissing the RCB indulged in shot making. bowled by Stoinis (0/23) that captain for 12 in the fourth Stoinis took on Washington included three sixes. over. In the very next ball, Sundar in the 12th over, hit- Rajat Patidar (31) and Glenn Ishant, playing his first match ting two fours while Pant Maxwell (25 off 20 balls) also of the season, got rid of the STATE TIMES NEWS Shimron Hetmyer (53 not smashed Patel for back-to-back provided valuable contribu- dangerous Padikkal. AHMEDABAD: Royal out off 25) displayed some sen- boundaries in the next over. Challengers Bangalore rode on sational hitting while batting However, an edge resulted in SCORE BOARD an AB de Villiers special and a alongside Pant (58 not out off the Australian all-rounder Winners posing for a group photograph at Mandal Cricket ground in Jammu. -

P26n.Qxp:Layout 1

26 Sports Thursday, July 18, 2019 Dung and Dragons: Myanmar kids dodge cows to play rugby An incongruous sight in a country where the sport is barely known YANGON: Sidestepping cowpats and garbage, Second-hand trainers Myanmar’s only home-grown junior rugby side train on the As the only homegrown junior team in the country, the outskirts of Yangon, preparing to take on children from the Little Dragons look to Yangon’s international schools for city’s well-heeled international schools. When the Little matches. In May, they took part in Myanmar’s first junior Dragons aren’t running barefoot on the litter-strewn dirt, tournament — partly played on a full-sized, artificial the makeshift field on the outskirts of Yangon is sometimes grass pitch at one of the schools. Out of 10 teams in each used as a cockfighting ring or a fairground. age group, Little Dragons sides finished second and third But every Sunday, boys and girls aged five to 18 from in the Under-14s, and second in the Under-11s. “These Yangon’s North Dagon township can be seen playing kids ran rings round them,” says coach Bradley Edwards. touch rugby, an incongruous sight in a country where the One baffled team even tried removing their trainers to sport is barely known. As novice monks file past collecting see if that was the key to the Little Dragons’ agility — an alms, the players shoo away cantankerous cattle to begin experiment that lasted only a couple of minutes on the warm-up drills under the tutelage of their coaches, a mix hot, rough surface. -

Foakes Debut Leads England Revival for Long-Awaited Test Win AFP | Galle, Sri Lanka AFP | Sylhet, Bangladesh Ing Pakistan in Harare in 2013

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2018 16 Sharma guides India Rohit Sharma’s record ton helps India clinch T20 series against West Indies AFP | Lucknow, India Sharma, who now has 2,203 runs in 86 matches, became India’s highest India kipper Rohit run-scorer in T20s after surpassing R. Sharma not out 111 Sharma smashed regular captain Virat Kohli (2,102 runs) S. Dhawan c Pooran b Allen 43 Shis fourth Twen- during his red-hot knock. R. Pant c Hetmyer b Pierre 5 ty20 international He is now the second highest scorer KNOW WHAT L. Rahul not out 26 century -- the most in the world behind Extras (nb2, w8) 10 by any batsman in New Zealand’s Martin Guptill, on Total (2 wickets, 20 overs) 195 the format -- to set 2,271 runs. Bowling: Thomas 4-1-27-0 (nb1), Paul 4-0-30-0 up India’s con- The right-left combination of Sharma Playing his 86th T20I, (nb1, w2), Pierre 4-0-49-1 (w4), Brathwaite 4-0- vincing 71-run and Dhawan, who surpassed 1,000 T20 Rohit Sharma surpassed 56-0 (w1), Allen 4-0-33-1 (w1) series-clinch- runs during his 41-ball knock, smashed Virat Kohli’s tally of 2102 ing win over the balls to all parts of the huge ground runs to become India’s West Indies (target 193) West indies before the first wicket fell in the 14th S. Hope b Ahmed 6 yesterday. over. highest run-getter S. Hetmyer c Dhawan b Ahmed 15 Shar- Dhawan, who survived a dropped D. -

N E W C L O S E N E

N E W C L O S E N E W S September 2020 photo © Dave Reynolds Editor: Hugh Griffiths email: [email protected] mobile: 07768 552682 JOIN US AT NEWCLOSE ON SUNDAY 13TH SEPTEMBER Whilst the Marylebone Cricket Club is widely recognised for its ownership of Lord’s Cricket Ground and cricketing traditions, a lesser known aspect of the Club’s activities is the work of the MCC Foundation in developing cricket for girls (and youngsters in general) - as described in this short video: https://youtu.be/qRIpd7Bh7q0 At 9.30am there’ll be an ECB Women’s Big Cricket Weekend event with Girls cricket back on the Isle of Wight after an absence of 8 years. This will allow the girls to showcase their development and enthusiasm. At 12.00 noon there’ll be a 40 overs-a-side match between an Isle of Wight XI and the MCC, for the Keith Newbery Memorial Trophy. The IW Cricket Board Coach, Andy Woodward, has been able to arrange the fixture which follows a MCC match against Ryde School on Saturday 12th September (which starts at 1.00pm). THE PAVILION WILL BE OPEN FOR MEMBERS AND THEIR GUESTS FROM 9.00AM SERVING EGGS AND BACON (OF COURSE!) - AND THROUGHOUT THE DAY OFFERING LIGHT REFRESHMENTS, LUNCHES AND DRINKS. Two weeks later, on Sunday 27th September (not Sunday 20th September as previously advised), we close the season with the NEWCLOSE CRICKET CLUB PRESIDENT’S DAY of cricket and social events - culminating in the Newclose End of Season party at close of play. -

Stumped at the Supermarket: Making Sense of Nutrition Rating Systems 2 Table of Contents

Stumped at the Supermarket Making Sense of Nutrition Rating Systems 2010 Kate Armstrong, JD Public Health Law Center, William Mitchell College of Law St. Paul, Minnesota Commissioned by the National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (NPLAN) nplan.org phlpnet.org Support for this paper was provided by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, through the National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (NPLAN). NPLAN is a program of Public Health Law & Policy (PHLP). PHLP is a nonprofit organization that provides legal information on matters relating to public health. The legal information provided in this document does not constitute legal advice or legal representation. For legal advice, readers should consult a lawyer in their state. Stumped at the Supermarket: Making Sense of Nutrition Rating Systems 2 Table of Contents Introduction . 4 Emergence of Nutrition Rating Systems in the United States . 6 Health Organization Labels . 6 Food Manufacturers’ Front-of-Package Labeling Systems (2004-2007) . 7 Food Retailers’ Nutrition Scoring and Rating Systems (2006-2009) . 10 Development and Suspension of Smart Choices (2007-2009). .14 Nutrition Rating Systems: A Bad Idea, or Just Too Much of a Good Thing? . 21 A Critique of Nutrition Rating Systems . 21 Multiple Nutrition Rating Systems: Causing Consumer Confusion? . 25 Nutrition Rating Systems Abroad: Lessons Learned from Foreign Examples . .27 FDA Regulation of Point-of-Purchase Food Labeling: Implications for Nutrition Rating Systems . 31 Overview of FDA’s Regulatory Authority Over Food Labeling . 31 Past FDA Activity Surrounding Front-of-Package Labeling and Nutrition Rating Systems . 33 Recent and Future FDA Activity Surrounding Point-of-Purchase Food Labeling .