Joshua Reynolds in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

Joshua Reynolds's “Nice Chymistry”: Action and Accident in the 1770S Matthew C

This article was downloaded by: [McGill University Library] On: 06 May 2015, At: 11:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Art Bulletin Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Joshua Reynolds's “Nice Chymistry”: Action and Accident in the 1770s Matthew C. Hunter Published online: 03 Mar 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Matthew C. Hunter (2015) Joshua Reynolds's “Nice Chymistry”: Action and Accident in the 1770s, The Art Bulletin, 97:1, 58-76, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2014.943125 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2014.943125 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Lot and His Daughters Pen and Brown Ink and Brown Wash, with Traces of Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri GUERCINO (Cento 1591 - Bologna 1666) Lot and his Daughters Pen and brown ink and brown wash, with traces of framing lines in brown ink. Laid down on an 18th century English mount, inscribed Guercino at the bottom. Numbered 544. at the upper right of the mount. 180 x 235 mm. (7 1/8 x 8 7/8 in.) This drawing is a preparatory compositional study for one of the most significant works of Guercino’s early career; the large canvas of Lot and His Daughters painted in 1617 for Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, the archbishop of Bologna and later Pope Gregory XV, and today in the monastery of San Lorenzo at El Escorial, near Madrid. This was one of three paintings commissioned from Guercino by Cardinal Ludovisi executed in 1617, the others being a Return of the Prodigal Son and a Susanna and the Elders. The Lot and His Daughters is recorded in inventories of the Villa Ludovisi in Rome in 1623 and 1633, but in 1664 both it and the Susanna and the Elders were presented by Prince Niccolò Ludovisi, nephew of Gregory XV, to King Phillip IV of Spain. The two paintings were placed in the Escorial, where the Lot and His Daughters remains today, while the Susanna and the Elders was transferred in 1814 to the Palacio Real in Madrid and is now in the Prado. Painted when the artist was in his late twenties, the Lot and his Daughters is thought to have been the first of the four Ludovisi pictures to be painted by Guercino. -

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

Florence and the Netherlands

EXHIBITION REVIEWS introductory essays, especially those by Lorne Campbell and Jennifer Fletcher, the former’s above-mentioned Renaissance Portraits often shines through. Multi-authored books rarely make for a comprehensive, well-integrated approach to a subject, and it would be wel - come if Campbell’s book, which has long been out of print, could be reissued. 1 L. Campbell: Renaissance Portraits: European Portrait- Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries , New Haven and London 1990. 2 Catalogue: El retrato del Renacimiento . Edited by Miguel Falomir, with essays by Miguel Falomir, Luke Syson, Alexander Nagel, Lorne Campbell, Jennifer Fletcher, Joanna Woods-Marsden, Juan Luis González García and Michael Bury. 544 pp. incl. 230 col. + 19 b. & w. ills. (Museo Nacional del Prado and Editiones El Viso, Madrid, 2008), 50. ISBN 978–84–95241– € 56–6. An English translation of the essays and entries is included at the back of the book. 3 There will be a different catalogue to accompany the London show, with essays by Luke Syson, Lorne Campbell, Jennifer Fletcher and Miguel Falomir; catalogue: Renaissance Faces: Van Eyck to Titian , £35 (HB). ISBN 9781 –857 –0941 –14; £19.95 (PB). ISBN 978 –1–857 –0940 –77. 4 The central theme of the exhibition Firenze e gli antichi Paesi Bassi 1430–1530 at the Palazzo Pitti, Florence 81. St Jerome in his study , by Jan van Eyck?. Paper (to 26th October), reviewed below. 80. St Jerome in his study , by Domenico Ghirlandaio. mounted on panel, 20.6 by 13.3 cm. (Detroit 5 L. Silver: The paintings of Quinten Massys with a 1480. -

Sir Joshua Reynolds 1723-1792 Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds 1723-1792 Joshua Reynolds (RIN ulz) was born in Plympton, Devonshire in England. His father, who was the headmaster of the grammar school in his town, was his teacher. When he was twelve he painted a portrait on sailcloth working with the paint they used in the shipyard. It was not a great painting, but it did demonstrate his talent, and his father allowed him to become an apprentice to an artist. He studied with Thomas Hudson in London and became a better artist than his teacher. Hudson became jealous and dismissed him as his pupil. Reynolds studied the works of different artists in Italy for three years and became one of the best portrait painters of his time. After spending time in Italy he began to incorporate the Italian style in his painting, sometimes putting his subjects dressed in flowing robes in Italian settings with columns and statues. He wanted his subjects dressed in elegant clothing. Velvet and lace lended majesty to a painting. He was very particular about this and once had the Duchess of Rutledge try on eleven dresses before he found the right one for the painting. He knew historical pictures didn't sell well, but people did like to have pictures of themselves; portraits. By the time he was 32 years old he had painted 100 portraits for people. The painting featured in this lesson George Clive and His Family was painted in 1765. Clive was an elected member of the British Parliament serving for 16 years. He and his wife Syndey had several children including Edward. -

Aesthetical Issues of Leonardo Da Vinci's and Pablo Picasso's

heritage Article Aesthetical Issues of Leonardo Da Vinci’s and Pablo Picasso’s Paintings with Stochastic Evaluation G.-Fivos Sargentis * , Panayiotis Dimitriadis and Demetris Koutsoyiannis Laboratory of Hydrology and Water Resources Development, School of Civil Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Heroon Polytechneiou 9, 157 80 Zographou, Greece; [email protected] (P.D.); [email protected] (D.K.) * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 7 April 2020; Accepted: 21 April 2020; Published: 25 April 2020 Abstract: A physical process is characterized as complex when it is difficult to analyze or explain in a simple way. The complexity within an art painting is expected to be high, possibly comparable to that of nature. Therefore, constructions of artists (e.g., paintings, music, literature, etc.) are expected to be also of high complexity since they are produced by numerous human (e.g., logic, instinct, emotions, etc.) and non-human (e.g., quality of paints, paper, tools, etc.) processes interacting with each other in a complex manner. The result of the interaction among various processes is not a white-noise behavior, but one where clusters of high or low values of quantified attributes appear in a non-predictive manner, thus highly increasing the uncertainty and the variability. In this work, we analyze stochastic patterns in terms of the dependence structure of art paintings of Da Vinci and Picasso with a stochastic 2D tool and investigate the similarities or differences among the artworks. Keywords: aesthetic of art paintings; stochastic analysis of images; Leonardo Da Vinci; Pablo Picasso 1. Introduction The meaning of beauty is linked to the evolution of human civilization, and the analysis of the connection between the observer and the beauty in art and nature has always been of high interest in both philosophy and science. -

Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds

"Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wendorf, Richard. 2000. "Well said Mr. Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's annotated copy of James Northcote's biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Harvard Library Bulletin 9 (4), Winter 1998: 29-40. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363299 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 29 "Well said M~ Northcote": Hester Thrale Piozzi's Annotated Copy of James Northcote's Biography of Sir Joshua Reynolds Richard Wendoif ester Lynch Thrale Piozzi was of two minds about Sir Joshua RICHARD WENDORF is the Reynolds. She greatly admired him as a painter-or at least as a Stanford Calderwood H painter of portraits. When he attempted to soar beyond portraiture Director and Librarian of into the realm of history painting, she found him to be embarrassingly the Boston Athena:um. out of his depth. Reynolds professed "the Sublime of Painting I think," she wrote in her voluminous commonplace book, "with the same Affectation as Gray does in Poetry, both of them tame quiet Characters by Nature, but forced into Fire by Artifice & Effort." 1 As a portrait-painter, however, Reynolds impressed her as having no equal, and she took great pride in his series of portraits commissioned by her first husband, Henry Thrale, for the library at their house in Streatham. -

The Cult of the Celebrity: Omai, the Exotic and Joshua Reynolds This

The Cult of the Celebrity: Omai, the Exotic and Joshua Reynolds This lecture I will look at the events that led up to Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Omai becoming an emblematic and iconic image representing Britain at the very height of its imperial powers. To explore this famous moment from history when two worlds collided I will explore the key players in Omai’s story, his origins in Tahiti, his background and motivation to come to England, followed by his time in England and English society and his interaction therein. I will then go on to look at Joshua Reynolds’s ideas regarding his self image, his influences and how this related to his image of Omai. This will be followed by a look at what this portrait of Omai by Joshua Reynolds can tell us about 18th century English society, its perception or preconception of the Other or non-white European and how prevalent pseudo-scientific ideas in this period affected the way Omai was perceived and finally envisioned in Reynolds’s painting. I will then look at what happened when Omai returned to the South Seas and impact of going back; can one ever go back what is the impact of returning? Finally I will speak about the legacy of the image we call Omai, which has become an enigma in its own right. Short Reading list: House, John, Impressionism for England: Samuel Courtauld as Patron and Collector, (Yale University Press, 1994) Kaeppler, Adrianne L., Head Curator, James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific, (Thames and Hudson, 2010) Rendle-Short, Francesca, (Ed), Cook & Omai: The Cult of the South Seas, (National Library of Australia, 2001) Postle, Martin, (Ed), Joshua Reynolds: The Creation of Celebrity, (Tate Publishing, 2005) 31/03/2009 - ©Leslie Primo Art First - www.primoartdiscoverytours.co.uk . -

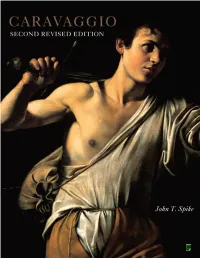

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio.