Letter to Spring Arbor University Kenneth Deaver Grand Valley State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 NCCAA Softball Awards

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Softball News Releases Softball Spring 2008 2008 NCCAA Softball Awards Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/softball_news_releases Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Softball News Releases by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Welcome to the NCCAA: National Christian College Athletic Association Page 1 of 3 NCCAA Home / W Suftb,llHome/W Softboll Ar.J,ivos /W Softball Awards / W Softball Cha]lli>ionshi11J W Softball Photos / W..Softball Stats / :W_Softball Handbook AWAAOS BMW CHARITY PRO-AM Women's Softball Awards EVENTS MEMBER SCHOOLS 2008Awards NEWSROOM PREFERRED VENDORS Coach of the Year Ritchie Richardson, Olivet Nazarene University PRESJDENT'S CUP R.ECENE CHRIST Player of the Year Lauren Chessum, Olivet Nazarene University SPOP:T'S SUPPORT NCCAA Scholar-Athletes .Q_edarville University Sarah Hoffman, Junior, Psychology Rachel Ross, Junior Political Science Charissa Rowe, Junior, Pre-Law & History Andrea Walker, Senior, Christian Education Emmanuel C_oll~ e Shana Gibbs, Senior Kasey Reed, Senior, Kinesiology Haley Freeman, Senior, Business Jennifer Howard, Senior, Business Diana Robinson, Senior, Communications Caitlyn Bryan, Junior, Communications -

Men's Basketball DI History

Men’s Basketball DI History (Click Refresh upon opening this file for the most current data) Champions ∙ Coach of the Year ∙ Pete Maravich Award 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 MEN'S BASKETBALL DIVISION I CHAMPIONS 1968 - Lee College 1969 - Azusa Pacific College 1970 - Azusa Pacific College 1971 - Azusa Pacific College 1972 - Azusa Pacific College 1973 - Lee College 1974 - Bethany Nazarene College 1975 - Olivet Nazarene College 1976 - Biola University 1977 - Bethany Nazarene College 1978 - Biola University 1979 - Tennessee Temple University 1980 - Liberty Baptist College 1981 - Tennessee Temple University 1982 - Tennessee Temple University 1983 - Tennessee Temple University 1984 - Biola University 1985 - Point Loma Nazarene University 1986 - Point Loma Nazarene University 1987 - Point Loma Nazarene University 1988 - Tennessee Temple University 1989 - Tennessee Temple University 1990 - Christian Heritage College 1991 - John Brown University 1992 - Bethel College 1993 - Bethel College 1994 - Lee College 1995 - Indiana Wesleyan University 1996 - Malone College 1997 - Christian Heritage College 1998 - Christian Heritage College 1999 - Oakland City University 2000 - Bethel College 2001 - Geneva College* 2002 - Mt. Vernon Nazarene University 2003 - Tennessee Temple University 2004 - Christian Heritage College 2005 - Spring Arbor University -

Graduate Catalog

2014-2015 GRADUATE CATALOG SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Master of Arts in Communication Master of Arts in Spiritual Formation and Leadership GAINEY SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Master of Business Administration SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Master of Arts in Education Master of Arts in Reading Master of Special Education Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages SCHOOL OF HUMAN SERVICES Master of Arts in Counseling Master of Arts in Family Studies Master of Science in Nursing Master of Social Work Spring Arbor University is a Christian liberal arts university accredited through the Higher Learning Commission 30 North LaSalle Street, Suite 2400, Chicago, IL 60602-2504 PH: 312.263.0456 THE SPRING ARBOR UNIVERSITY CONCEPT Spring Arbor University is a community of learners distinguished by our lifelong involvement in the study and application of the liberal arts, total commitment to Jesus Christ as the perspective for learning, and critical participation in the contemporary world. 2 FROM THE PROVOST AND CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER Welcome to Spring Arbor University’s graduate degree programs! We are delighted that you are a member of our 140-year-old Community of Learners. Together we will study and learn to apply the Liberal Arts to build our ability to be life-long learners, always embracing and upholding Jesus Christ as the perspective for that learning, with the intention to be critical participants in the contemporary world. thought and practice of your chosen profession. Our courses, programs and degrees are designed with the intention of giving you knowledge and skills to aid you in that contribution. -

PDF.Js Viewer

Seago, Shawn East Texas Baptist Bible College Stults, Eric Bethel College Zobrist, Ben Olivet Nazarene University Tournament MVP Adair, Reed Faulkner University Scholar Athletes Batthauer, Brian Olivet Nazarene University Bishop, Ryan Malone College Bolemon, Britt Emmanuel College Boston, Jonathan Malone College Clewis, Jason Emmanuel College Culp, Bill Geneva College D'Angelo, Dave Geneva College Freels, Eric Trinity International University (IL) Grater, Gary Geneva College Heefner, Dan Olivet Nazarene University Hicks, Brent Oakland City University Janicki, Ron Geneva College Lavin, Jeff Mount Vernon Nazarene College Pene, Robert Spring Arbor University Ruso, Derek Geneva College Wibbeler, Brad Oakland City University Wine, Jeff Mount Vernon Nazarene College National Player of the Year Heimbach, Andy Mount Vernon Nazarene College Unlimited Potential Player of the Year Forman, Wayne Spring Arbor University Coach of the Year Barker, Brent Faulkner University 2000 Championship Championship Indiana Wesleyan University Marion, Indiana May 24-27, 2000 Round 1 Results Malone vs. Nyack (3-2) East Texas Baptist vs. Indiana Wesleyan (6-4) Faulkner vs. Emmanuel (4-0) Oakland City vs. Trinity Christian (13-6) Malone vs. Olivet Nazarene (15-3) Spring Arbor vs. Oakland City (13-2) Round 2 Results Emmanuel vs. Trinity Christian (9-0) Indiana Wesleyan vs. Nyack (12-0) Olivet Nazarene vs. Emmanuel (14-0) Oakland City vs. Indiana Wesleyan (6-2) Round 3 Results Malone vs. East Texas Baptist (9-2) Faulkner vs. Spring Arbor (15-3) Round 4 Results Olivet Nazarene vs. East Texas Baptist (6-3) Spring Arbor vs. Oakland City (9-8) Final 4 Olivet Nazarene vs. Faulkner (7-1) Spring Arbor vs. -

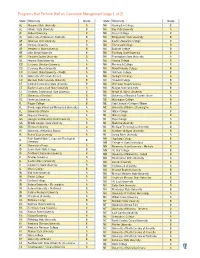

Programs That Perform Well on Classroom Management (Page 1 of 2)

Programs that Perform Well on Classroom Management (page 1 of 2) State University Grade State University Grade AL Alabama State University A MA Assumption College B AL Athens State University B MA Bay Path University A AL Auburn University B MA Boston College B AL University of Alabama in Huntsville B MA Bridgewater State University B AR Arkansas Tech University B MA Eastern Nazarene College B AR Harding University B MA Emmanuel College B AR Henderson State University B MA Endicott College B AR John Brown University B MA Fitchburg State University B AR Ouachita Baptist University B MA Framingham State University A AZ Arizona State University A MA Gordon College B CO Colorado Christian University A MA Merrimack College B CO Colorado Mesa University B MA Mount Holyoke College B CO Colorado State University – Pueblo A MA Simmons College B CO University of Colorado Denver A MA Springfield College A CO Western State Colorado University B MA Stonehill College B CT Central Connecticut State University B MA Worcester State University B CT Eastern Connecticut State University A MD Morgan State University B CT Southern Connecticut State University B MD Mount St. Mary’s University B CT University of Hartford B MD University of Maryland Eastern Shore A DC American University B MD Washington College B FL Flagler College B ME Saint Joseph’s College of Maine B FL Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University A ME University of Maine at Farmington A FL University of Miami A MI Albion College B GA Augusta University A MI Alma College B GA Georgia Southwestern State University A MI Hope College A GA Middle Georgia State University B MI Madonna University B GA Thomas University A MI Michigan Technological University B HI University of Hawaii at Manoa A MI Northern Michigan University B IA Buena Vista University A MI Spring Arbor University A Faith Baptist Bible College and Theological MN Augsburg College B IA B Seminary MN College of Saint Scholastica B IA University of Iowa A MN Minnesota State University – Mankato B ID Lewis-Clark State College B MN St. -

President's Report Web.Indd

P RESIDENT ’ S R E P O R T 2 0 0 6 contents president’s remarks resident’s report 2006 resident’s p 2 laura foudy I spent six days in the Czech Republic with in Prague, Karlovy-Vary and the Czech crossing cultures leads to Kenya Paul Nemecek ’81, associate professor of countryside; and interacting with a whole 4 sociology and adult studies, and 15 of our array of government and cultural leaders brightest students in May 2005. It was was thrilling. But it was troubling, too. We mark janowiak an opportunity for me to gain brief and witnessed first-hand the troubled history UNIVERSITY ongoing exposure to our dynamic cross of this beautiful nation-state and traveled a world without boundaries 6 cultural programs. It also provided me to many of the haunting reminders of the with one of my favorite opportunities: the horrors of human evil that have run across joel maust chance to see another culture in action and this land. The Czech Republic is a living to consider the many ways societies are reminder of what can go so gloriously right SPRING ARBOR katrina: reflecting on relief 8 structured around the world. and what can go so horribly wrong when There is no question I loved the human ideals run amok. richard tallman experience — being with students for six Today, I sit in the luxury of my 14 days in gulfport days, spending major portions of time office thinking of that dear time and 10 SAU timeline 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 board of trustees 11 New leadership New name Spring Arbor Total enrollment 3,174; buildings Gayle D. -

THE 2017 MARIAN OPEN CROSS COUNTRY MEET September 15, 2017 -- Northview Church

THE 2017 MARIAN OPEN CROSS COUNTRY MEET September 15, 2017 -- Northview Church *********** TEAM SCORE ********** Mens 1. Taylor University 1 3 5 8 9 (11) (19) = 26 Josh Roth, Ben Byrd, Jonathan Taylor, Hunter Smith, Andrew Runion, Daniel Gerber, Stephen Cho 2. Indiana Wesleyan Universi 4 6 7 12 13 (16) (23) = 42 Christian Cuevas, Jared Williams, Landon Miller, Chris Maxon, Josh Brocato, Adam Fields, Caleb Smith 3. Goshen College 14 20 22 27 28 (32) (34) = 111 Vincent Kibunja, Juan Perez, Steven Cranston, Quinton Read, Isaiah Friesen, Salvador Escamilla, Brenner Burkholder 4. Grace College 2 18 31 33 38 (39) (47) = 122 Carter Meyer, Sam Hall, Elijah Brooks, Ben Rankin, Jonathan Balda, Blake Kirkham, Brendan Hamilton 5. Marian University Indiana 10 21 25 41 43 (44) (56) = 140 MICHAEL CONTE, CONOR SMITH, MARCUS FIEREK, DANIEL SANTOS, MATT WIELGUS, ANGEL SOTO-LOZADA, LUKE SCHROERING 6. Huntington University 15 17 24 42 46 (50) (54) = 144 Elijah Chesterman, Kevin Moser, Nick Childs, Codi Wiersema, Elston Jones, Adren Gentie, Zach McIntyre 7. Bethel College (Ind.) 29 30 35 37 40 (45) (49) = 171 Chad Williams, Evan Herr-Knispel, Erick Contreras, Alexander DeLuna, Justin Contreras, Collin Wiersema, Kole Hanke 8. Spring Arbor University 26 36 48 51 52 (53) (55) = 213 Ian Fulton, Max Whittredge, Trent Smith, Justin Detgen, Dylan Hamilton, Cameron Kyser, David Williams Place No. Name School Time Pace ===== ==== ======================== ======================================== ======== ===== 1 838 Josh Roth Taylor University 26:43.91 5:23 2 668 Carter -

2018-2019 Graduate Catalog

2018-2019 GRADUATE CATALOG 106 E. Main St. Spring Arbor, Michigan 49283 www.arbor.edu P a g e | 1 Spring Arbor University 2018-19 Graduate Catalog 2018-2019 GRADUATE CATALOG Spring Arbor University is a Christian liberal arts university accredited through the Higher Learning Commission 30 North LaSalle Street, Suite 2400, Chicago, IL 60602-2504 PH: 312.263.0456 P a g e | 2 Spring Arbor University 2018-19 Graduate Catalog General Information Table of Contents GRADUATE PROGRAM INFORMATION GENERAL INFORMATION 4 ADMISSIONS 15 ACADEMIC POLICIES 18 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS 29 GAINEY SCHOOL OF BUSINESS 30 MASTER OF ARTS IN MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL LEARDERSHIP 31 MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 33 SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES 39 MASTER OF ARTS IN STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION AND LEADERSHIP 40 SCHOOL OF EDUCATION 45 MASTER OF ARTS IN EARLY CHILDHOOD 50 MASTER OF ARTS IN EDUCATION 51 MASTER OF ARTS IN READING 52 MASTER OF ARTS IN TESOL 53 MASTER OF SPECIAL EDUCATION 56 SCHOOL OF HUMAN SERVICES 69 MASTER OF ARTS IN COUNSELING 70 MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING 81 MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK 90 NONPROFIT LEADERSHIP AND ADMINISTRATION ENDORSEMENT 102 University Administration 103 P a g e | 3 Spring Arbor University 2018-19 Graduate Catalog General Information GENERAL INFORMATION CATALOG DISCLAIMER The Spring Arbor University catalog contains information about the University and policies relating to the academic requirements and records of each student. Current and future students should refer to individual program handbooks for additional information. The University’s policies and procedures may not be varied by any University employee without official governance approval either in writing or by an oral statement, Curricula and policies listed in this catalog are subject to change through normal University governance procedures. -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

Undergraduate Academic Catalog 2016-17

Grand Rapids, Michigan Undergraduate Academic Catalog 2016-2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016-2017 Academic Calendar . 4 A Letter from the President . 5 About Cornerstone . 7 Student Development. 13 Campus Life . 15 Admissions . .21 Financial Information . 25 Academic Information . 35 Off-Campus Programs . 47 Degree Information . .. 53 Designing a Program . 61 Bible, Religion & Ministry Division . 65 Business Division . .. 77 Communication & Media Division . 93 Humanities Division. 111 Interdisciplinary Studies Division . 129 Kinesiology, Science & Mathematics Division . 133 Music Division. 157 Social Science Division . 167 Teacher Education Division . 181 Index. 203 3 | BUILD A LIFE THAT MATTERS 2016-2017 ACADEMIC CALENDAR FALL 2016 Terra Firma Arrival . .Sept . 2 Residence Halls Open/Returning Students Move In . Sept . 5-6 Labor Day (No Classes) . .Sept . 5 Classes Begin . .Sept . 7 Drop/Add . Sept . 7-13 Family Weekend . .Sept . 30-Oct . 1 Fall Break . Oct . 10-11 Mid-Term . Oct . 12-14 Registration Begins . Oct . 17 Last Day to Withdraw without W/P or W/E . Nov . 15 Thanksgiving Break . Nov . 23-27 Classes Resume . Nov . 28 Last Day to Withdraw without W/E . Dec . 6 Final Day of Classes . Dec . 9 Final Exams . Dec . 12-15 Residence Halls Close . .Dec . 15 Final Grades Due at Noon . Dec . 20 SPRING 2017 Residence Halls Open for J-Term . .Jan . 3 J-Term . Jan . 4-17 Residence Halls Open for Spring Term . Jan . 18 Classes Begin . Jan . 19 Drop/Add . Jan . 19-25 Spring Break . March 6-10 Classes Resume . March 13 Registration Begins . March 15 Mid-Term . .March 20-23 Last Day for Withdrawal without W/P or W/E . -

2017-18 Undergraduate Catalog

2017-2018 Undergraduate Catalog THE SPRING ARBOR UNIVERSITY CONCEPT Spring Arbor University is a community of learners, distinguished by our lifelong involvement in the study and application of the liberal arts, total commitment to Jesus Christ as the perspective for learning, and critical participation in the contemporary world. 1 Spring Arbor University Academic Undergraduate Catalog 2017-2018 2 Spring Arbor University Academic Undergraduate Catalog 2017-2018 FROM THE PROVOST In 1873 Spring Arbor Seminary was founded. Over fifty years ago, Spring Arbor College received its first four-year degree students. Spring Arbor has continued to offer the liberal arts permeated and undergirded by God’s truth as revealed in Jesus Christ as the foundation for lifelong learning and ongoing involvement in a changing world. Spring Arbor University now welcomes you to explore our majors, minors, and programs to identify those that will enable you best to attain your educational goals. This catalog provides program content, degree requirements, and information on specific courses for all of our undergraduate majors and minors. It is intended to be a guide and tool for you to identify a course of study to pursue, to work with your advisor in determining a plan to graduation, and to track your progress toward your degree achievement. The policies and expectations set forth in the pages following are designed to assure program quality, consistency, accountability and match with the values and mission of the University. Specifically, it delineates requirements that need to be met for graduations, majors, programs and so forth. You need to understand and abide by these requirements. -

Longing for a Life with God

Office of the President Longing for a life with God his past year I had the wonderful privilege of the great questions of life that guide every honest taking a short-term sabbatical (Dec. 5, 2005- seeker. What is the meaning of life? How can a TJan. 30, 2006). During that time, I returned loving God allow suffering? Why would a good God to a project I have been thinking about for 25 permit so much evil? Is there proof for the existence years: How do we understand our life with God? of God? How can we begin to address and answer My own spiritual awakening occurred when I was this question? And if Jesus is the only way to God, an undergraduate student studying with Richard how do we understand the reality and persistence Foster during the same period in which he was of all these other religions? writing Celebration of Discipline. I had been in SPRING ARBOR Eventually, I would graduate from seminary, pastor Christian circles all my life, yet I had never read UNIVERSITY a church, return for my doctorate, and begin nor experienced such a thorough ordering of how CONCEPT we could understand and make progress in our life my current life in higher education. Still, these with God. As you can imagine, it was a thrilling time foundational questions, the ones that confront Spring Arbor University and the discoveries made during college continue each one of us, continue to rivet my attention. This is a community of to guide me to this day. past year I had the opportunity to speak to these learners distinguished by questions and to talk about our life with God in a our lifelong involvement Following college, I attended Princeton variety of contexts.