THE USE of ESSENTIAL DRUGS Model List of Essential Drugs (Seventh List)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avant-Propos Le Format De Présentation De Cette Thèse Correspond À Une Recommandation À La Spécialité

Avant-propos Le format de présentation de cette thèse correspond à une recommandation à la spécialité Maladies infectieuses, à l’intérieur du Master des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé qui dépend de l’Ecole Doctorale des Sciences de la Vie de Marseille. Le candidat est amené à respecter les règles qui lui sont imposées et qui comportent un format de thèse utilisé dans le Nord de l’Europe et qui permet un meilleur rangement que les thèses traditionnelles. Par ailleurs, la partie introduction et bibliographie est remplacée par une revue envoyée dans un journal afin de permettre une évaluation extérieure de la qualité de la revue et de permettre à l’étudiant de commencer le plus tôt possible une bibliographie sur le domaine de cette thèse. Par ailleurs, la thèse est présentée sur article publié, accepté, ou soumis associé d’un bref commentaire donnant le sens général du travail. Cette forme de présentation a paru plus en adéquation avec les exigences de la compétition internationale et permet de se concentrer sur des travaux qui bénéficieront d’une diffusion internationale. Professeur Didier RAOULT 2 Remerciements J’adresse mes remerciements aux personnes qui ont contribué à la réalisation de ce travail. En premier lieu, au Professeur Didier RALOUT, qui m’a accueillie au sein de l’IHU Méditerranée Infection. Au Professeur Serge MORAND, au Docteur Marie KEMPF et au Professeur Philippe COLSON de m’avoir honorée en acceptant d’être rapporteurs et examinateurs de cette thèse. Je souhaite particulièrement remercier : Le Professeur Jean-Marc ROLAIN, de m’avoir accueillie dans son équipe et m’avoir orientée et soutenue tout au long de ces trois années de thèse. -

Rapport 2008

rapport 2008 Reseptregisteret 2004-2007 The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004-2007 Marit Rønning Christian Lie Berg Kari Furu Irene Litleskare Solveig Sakshaug Hanne Strøm Rapport 2008 Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt/ The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Tittel/Title: Reseptregisteret 2004-2007 The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004-2007 Redaktør/Editor: Marit Rønning Forfattere/Authors: Christian Lie Berg Kari Furu Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Hanne Strøm Publisert av/Published by: Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt Postboks 4404 Nydalen NO-0403 Norway Tel: + 47 21 07 70 00 E-mail: [email protected] www.fhi.no Design: Per Kristian Svendsen Layout: Grete Søimer Acknowledgement: Julie D.W. Johansen (English version) Forsideillustrasjon/Front page illustration: Colourbox.com Trykk/Print: Nordberg Trykk AS Opplag/ Number printed: 1200 Bestilling/Order: [email protected] Fax: +47-21 07 81 05 Tel: +47-21 07 82 00 ISSN: 0332-6535 ISBN: 978-82-8082-252-9 trykt utgave/printed version ISBN: 978-82-8082-253-6 elektronisk utgave/electronic version 2 Rapport 2008 • Folkehelseinstituttet Forord Bruken av legemidler i befolkningen er økende. En viktig målsetting for norsk legemiddelpolitikk er rasjonell legemiddelbruk. En forutsetning for arbeidet med å optimalisere legemiddelbruken i befolkningen er kunnskap om hvilke legemidler som brukes, hvem som bruker legemidlene og hvordan de brukes. For å få bedre kunnskap på dette området, vedtok Stortinget i desember 2002 å etablere et nasjonalt reseptbasert legemiddelregister (Reseptregisteret). Oppgaven med å etablere registeret ble gitt til Folkehelseinstituttet som fra 1. januar 2004 har mottatt månedlige opplysninger fra alle apotek om utlevering av legemidler til pasienter, leger og institusjoner. Denne rapporten er første utgave i en planlagt årlig statistikk fra Reseptregisteret. -

Official Title: a Randomized, Multicenter, Open-Label

Official Title: A Randomized, Multicenter, Open-Label Cross-Over Study to Evaluate Patient Preference and Satisfaction of Subcutaneous Administration of the Fixed-Dose Combination of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab in Patients With HER2-Positive Early Breast Cancer NCT Number: NCT03674112 Document Date: Protocol Version 2: 14-December-2018 PROTOCOL TITLE: A RANDOMIZED, MULTICENTER, OPEN-LABEL CROSS-OVER STUDY TO EVALUATE PATIENT PREFERENCE AND SATISFACTION OF SUBCUTANEOUS ADMINISTRATION OF THE FIXED-DOSE COMBINATION OF PERTUZUMAB AND TRASTUZUMAB IN PATIENTS WITH HER2- POSITIVE EARLY BREAST CANCER PROTOCOL NUMBER: MO40628 VERSION NUMBER: 2 EUDRACT NUMBER: 2018-002153-30 IND NUMBER: 131009 TEST PRODUCT: Fixed-dose combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab for subcutaneous administration (RO7198574) MEDICAL MONITOR: Dr. SPONSOR: F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd DATE FINAL: Version 1: 24 July 2018 DATE AMENDED: Version 2: See electronic date stamp below PROTOCOL AMENDMENT APPROVAL Approver's Name Title Date and Time (UTC) zCompany Signatory 14-Dec-2018 13:59:04 CONFIDENTIAL This clinical study is being sponsored globally by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd of Basel, Switzerland. However, it may be implemented in individual countries by Roche’s local affiliates, including Genentech, Inc. in the United States. The information contained in this document, especially any unpublished data, is the property of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (or under its control) and therefore is provided to you in confidence as an investigator, potential investigator, or consultant, for review by you, your staff, and an applicable Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board. It is understood that this information will not be disclosed to others without written authorization from Roche except to the extent necessary to obtain informed consent from persons to whom the drug may be administered. -

WHO Model Prescribing Information Drugs Used in Skin Diseases

WHO Model Prescribing Information Drugs used in Skin Diseases World Health Organization Geneva 1997 Contents Preface 1 Introduction 3 Parasitic infections 5 Pediculosis 5 Scabies 6 Cutaneous larva migrans (creeping eruption) 7 Gnathostomiasis 8 Insect and arachnid bites and stings 9 Mosquitos and other biting flies 9 Bees, wasps, hornets and ants 10 Bedbugs and reduviid bugs 11 Scorpions 11 Poisonous spiders 12 Chiggers or harvest mites 12 Ticks 13 Superficial fungal infections 14 Dermatophyte infections 14 Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor 16 Candidosis 17 Subcutaneous fungal infections 20 Sporotrichosis 20 Mycetoma 20 Chromomycosis 21 Subcutaneous zygomycosis 21 Bacterial infections 23 Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections 23 Yaws and pinta 25 Viral infections 27 Warts 27 Herpes simplex 28 Zoster and varicella 28 Molluscum contagiosum 29 Eczematous diseases 30 Contact dermatitis 30 Atopic dermatitis 31 Seborrhoeic dermatitis 32 Scaling diseases 34 Ichthyosis 34 Xerosis 34 Papulosquamous diseases 36 Lichen planus 36 Contents (continued) Pityriasis rosea 36 Psoriasis 37 Cutaneous reactions to drugs 40 Pigmentary disorders 42 Vitiligo 42 Melasma 42 Albinism 43 Premalignant lesions and malignant tumours 44 Actinic keratosis 44 Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas 45 Malignant melanoma 45 Photodermatoses 47 Solar urticaria 47 Polymorphous light eruptions 47 Actinic prurigo 48 Chemical photodermatoses 48 Bullous dermatoses 50 Pemphigus 50 Bullous pemphigoid 51 Dermatitis herpetiformis 52 Alopecia areata 53 Urticaria 54 Conditions common -

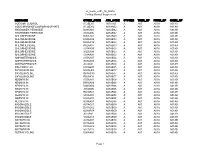

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Anti Infective Guideline 2012

UNIVERSITI KEBANGSAAN Malaysia National University of Malaysia PPUKM ANTI-INFECTIVE GUIDELINE 2012 All Rights Reserved. The authors, editor have every effort to provide accurate information at time of printing.The information in this book makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to accuracy or completeness of contents of the publication.Application of information remains the professional responsibility of the practititoner. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This guideline would not exist without the hard work from the Development Group who revised, checked, discuss, debated, designed, typed and reviewed as a team. We would like to thank the whole team for their effort and continuous commitment to help develop this Guideline. ANTI-INFECTIVE GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT GROUP 2011/2012 Y.Bhg. Prof. Dato’ Dr. Raymond Azman Ali Dean of Facuty of Medicine Director of UKM Medical Centre Members of the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee Prof Dr Jaafar Hj Md Zain Dato’ Dr Noorimi Hj Morad (Chairman) Chief Operations Officer, PPUKM Consultant Specialist Anesthesia and Intensive Care Deputy Dean of Clinical Services Prof Dr S Fadilah Abdul Wahid Prof (K) Dr. Abd. Hamid Abd Rahman Consultant Haematologist Consultant Psychiatrist Head, Department of Medicine & Cell Therapy Center Prof. Madya (K) Dr. Oteh Maskon Prof Madya Dr Razman Jarmin Consultant Cardiologist Consultant Specialist, Hepatobiliary Head, Cardiology Department Surgeon Head, Surgery Department Prof Dr Mohd Hashim Omar Prof Madya (Klinikal) Dato’ Dr Fuad Ismail Senior Consultant, Obstetric and Consultant -

Queensland Health List of Approved Medicines

Queensland Health List of Approved Medicines Drug Form Strength Restriction abacavir * For use in accord with PBS Section 100 indications * oral liquid See above 20 mg/mL See above tablet See above 300 mg See above abacavir + lamivudine * For use in accord with PBS Section 100 indications * tablet See above 600 mg + 300 mg See above abacavir + lamivudine + * For use in accord with PBS Section 100 indications * zidovudine tablet See above 300 mg + 150 mg + 300 mg See above abatacept injection 250 mg * For use in accord with PBS Section 100 indications * abciximab (a) Interventional Cardiologists for complex angioplasty (b) Interventional and Neuro-interventional Radiologists for rescue treatment of thromboembolic events that occur during neuroendovascular procedures. * Where a medicine is not TGA approved, patients should be made fully aware of the status of the medicine and appropriate consent obtained * injection See above 10 mg/5 mL See above abiraterone For use by medical oncologists as per the PBS indications for outpatient and discharge use only tablet See above 250 mg See above 500 mg See above acamprosate Drug and alcohol treatment physicians for use with a comprehensive treatment program for alcohol dependence with the goal of maintaining abstinence. enteric tablet See above 333 mg See above acarbose For non-insulin dependent diabetics with inadequate control despite diet; exercise and maximal tolerated doses of other anti-diabetic agents tablet See above 50 mg See above 100 mg See above acetazolamide injection 500 mg tablet 250 mg acetic acid ear drops 3% 15mL solution 2% 100mL green 3% 1 litre 6% 1 Litre 6% 200mL Generated on: 30-Aug-2021 Page 1 of 142 Drug Form Strength Restriction acetylcysteine injection For management of paracetamol overdose 2 g/10 mL See above 6 g/30 mL See above aciclovir cream Infectious disease physicians, haematologists and oncologists 5% See above eye ointment For use on the advice of Ophthalmologists only. -

Computerized Prescriber Order Entry Medication Safety (Cpoems)

COMPUTERIZED PRESCRIBER ORDER ENTRY MEDICATION SAFETY (CPOEMS) UNCOVERING AND LEARNING FROM ISSUES AND ERRORS Brigham and Women’s Hospital Harvard Medical School Partners HealthCare i CPOEMS: UNCOVERING AND LEARNING FROM ISSUES AND ERRORS This work was supported by contract HHSF223201000008I/HHSF22301005T from the US Food and Drug Administration (Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research). The views expressed in this publication, do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. ii CPOEMS: UNCOVERING AND LEARNING FROM ISSUES AND ERRORS CPOEMS CONTRIBUTORS BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Gordon Schiff, MD (Principal Investigator) Dr. Schiff is a general internist who joined the Brigham and Women's Hospital's Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care in 2007 as a clinician researcher in the area of patient safety and medical informatics and Associate Director of the Brigham Center for Patient Safety Research and Practice. He was the chair of the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Patient Education Consumer Interest Panel (1990-2000), and a member of the USP Medication Safety Expert Panel (2000-2005) as well as member of the Drug Information Division Executive Board (1990-2000). He is an author of numerous papers on CPOE and, most recently PI for the NPSF MedMarx CPOE Medication Error grant. He is the Safety Science Director for the Harvard Medical School Center for Primary Care Academic Innovations Collaborative. Dr. Schiff is currently the Co-PI on the AHRQ BWH HIT CERT, and PI for a newly funded AHRQ HIT Safety grant working to enhance CPOE by incorporating the drug indication into the prescription ordering. -

Cholinesterases Inhibitory Activity of 1H-Benzimidazole Derivatives

Article Volume 11, Issue 3, 2021, 10739 - 10745 https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC113.1073910745 Cholinesterases Inhibitory Activity of 1H-benzimidazole Derivatives Leila Dinparast 1,* , Gokhan Zengin 2 , Mir Babak Bahadori 3 1 Biotechnology Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; [email protected] (L.D.); 2 Department of Biology, Science Faculty, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey; [email protected] (G.Z.); 3 Medicinal Plants Research Center, Maragheh University of Medical Sciences, Maragheh, Iran; [email protected] (M.B.B.); * Correspondence: [email protected]; Scopus Author ID 26655477100 Received: 19.10.2020; Revised: 11.11.2020; Accepted: 12.11.2020; Published: 14.11.2020 Abstract: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that causes brain cells to waste away and die. The most common strategy for the treatment of AD is the inhibition of acetyl/butyrylcholinesterase (AChE and BChE) enzymes. Benzimidazole derivatives are important heterocyclic bioactive agents. In this study, in vitro inhibitory potential of 12 previously synthesized benzimidazoles was evaluated against acetyl/butyrylcholinesterases. Results showed that some derivatives have moderate AChE (IC50 = 1.01-1.19 mM) and BChE (IC50 = 1.1-1.87 mM) inhibitory activity. Findings could be helpful in the design and development of new effective anti-AD drugs with benzimidazole core. Keywords: benzimidazole; Alzheimer’s disease; acetylcholinesterase; butyrylcholinesterase. © 2020 by the authors. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). 1. Introduction Benzimidazole scaffold is an important nitrogen-containing heterocycle in organic and medicinal chemistry, which is found in numerous bioactive compounds [1, 2]. -

Eurasia Economic Union - New Pesticide Mrls Report Categories: Sanitary/Phytosanitary/Food Safety Approved By: Jonathan P Gressel Prepared By: FAS Moscow/Staff

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: GAIN Report Number: Russian Federation Post: Moscow Eurasia Economic Union - New Pesticide MRLs Report Categories: Sanitary/Phytosanitary/Food Safety Approved By: Jonathan P Gressel Prepared By: FAS Moscow/Staff Report Highlights: On November 10, 2015, the Eurasian Economic Commission adopted the Amendments to the Unified Sanitary-Epidemiological and Hygiene Requirements for Commodities Subject to Sanitary- Epidemiological Surveillance (Control). Adopted amendments concern requirements for pesticides and agrochemicals and Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for pesticides and chemicals in external entities, such as human body, soil, reservoir water, working air, open air, and in agricultural raw materials and food products. The document was published on November 18, 2015, and will come to force in a month after publication. The U.S. Government commented on the draft regulations in 2012. General Information: On November 10, 2015, the Eurasian Economic Commission, the working body of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), adopted the Decision No. 149 “On Amendments to the Decision of the Customs Union Commission No. 299 of May 28, 2010”. The Decision 299 of 2010 concerns the Unified Sanitary-Epidemiological and Hygiene Requirements for Commodities Subject to Sanitary-Epidemiological Surveillance (Control). Amendments that were made by the Decision No. 149 of November 10, 2015 cover the following: - Requirements for pesticides and agrochemicals (the non-official translation of these requirements is in Annex 2 to this report); - Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for pesticides and chemicals (573 chemicals) in external entities, such as human body, soil, reservoir water, working air, open air, and in agricultural raw materials and food products. -

Uniform Sanitary and Epidemiological and Hygienic Requirements for Products Subject to Sanitary and Epidemiological Supervision (Control)

983 Uniform Sanitary and Epidemiological and Hygienic Requirements for Products Subject to Sanitary and Epidemiological Supervision (Control) Chapter II Part 15. Requirements for Pesticides and Agrochemicals 984 I. REQUIREMENTS FOR PESTICIDES, IMPORTED AND PRODUCED IN THE TERRITORY OF THE CUSTOMS UNION MEMBER STATES (goods subject to control “insecticides, rodenticides, fungicides, herbicides, defoliants, desiccants, fumigants, anti-sprouting products and plant growth regulators” – code of the Commodity Nomenclature of Foreign Economic Activity of the Customs Union 3808) (as amended by Decision of the Customs Union Commission No 889 of 9 December 2011) 1. SCOPE OF APPLICATION Uniform Sanitary and Epidemiological and Hygienic Requirements (hereinafter referred to as the “Uniform Requirements”) shall apply to any pesticides produced and imported in the territory of the Customs Union Member States, regardless of the country of origin. The said requirements are developed on the basis of the legislation of the Customs Union Member States and effective international law documents and they are supposed to ensure the maximum safety of pesticides for humans and the environment. The Uniform Requirements are binding for all individuals and legal entities engaged in circulation of pesticides. Any breach of the Uniform Requirements shall result in administrative, disciplinary and criminal responsibility in accordance with the legislation of the Customs Union Member States. 2. TERMS AND DEFINITIONS Pesticide means any substance or mixture of substances intended for prevention of pest development, extermination of any pests (including any carriers of human and animal diseases) or pest and weed plants management as well as for the management of any pests which hinder production, processing, storage and transportation of food products, agricultural products, wood or animal feeding stuff; it also means any substances used as plant growth regulators, pheromones, defoliants, desiccants and fumigants. -

Review of Existing Classification Efforts

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.1.1 Review of existing classification efforts Due date of deliverable: (15.01.2008) Actual submission date: (07.02.2008) Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UGent Revision 1.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Task 4.1 : Review of existing classification efforts Authors: Kristof Pil, Elke Raes, Thomas Van den Neste, An-Sofie Goessaert, Jolien Veramme, Alain Verstraete (Ghent University, Belgium) Partners: - F. Javier Alvarez (work package leader), M. Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro (University of Valladolid, Spain) - Monica Colas, Juan Carlos Gonzalez-Luque (DGT, Spain) - Han de Gier, Sylvia Hummel, Sholeh Mobaser (University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Martina Albrecht, Michael Heiβing (Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon (University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Vassilis Papakostopoulos, Villy Portouli, Andriani Mousadakou (Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.1.1. Revision 1.0 Review of Existing Classification Efforts Page 2 of 127 Introduction DRUID work package 4 focusses on the classification and labeling of medicinal drugs according to their influence on driving performance.