Giant Sequoia National Monument (Monument)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, However, Went Unnoticed

• D -1:>K 1.2!;EQUOJA-KING$ Ci\NYON NATIONAL PARKS History of the Parks "''' Evaluation of Historic Resources Detennination of Effect, DCP Prepared by • A. Berle Clemensen DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEA.'! NATIONAL PAP.K SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPAR'J'}fENT OF THE l~TERIOR DENVER, COLOR..\DO SEPTEffilER 1975 i i• Pl.EA5!: RETUl1" TO: B&WScans TEallillCAL INFORMAl!tll CfNIEil 0 ·l'i «coo,;- OOIVER Sf:RV!Gf Cf!fT£R llAT!ONAL PARK S.:.'Ma j , • BRIEF HISTORY OF SEQUOIA Spanish and Mexican Period The first white men, the Spanish, entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1772. They, however, only observed the Sierra Nevada mountains. None entered the high terrain where the giant Sequoia exist. Only one explorer came close to the Sierra Nevadas. In 1806 Ensign Gabriel Moraga, venturing into the foothills, crossed and named the Rio de la Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings) or Kings River. Americans in the San Joaquin Valley The first band of Americans entered the Valley in 1827 when Jedediah Smith and a group of fur traders traversed it from south to north. This journey ushered in the first American frontier as fifteen years of fur trapping followed. Still, none of these men reported sighting the giant trees. It was not until 1833 that members of the Joseph R. 1lalker expedition crossed the Sierra Nevadas and received credit as the first whites to See the Sequoia trees. These trees are presumed to form part of either the present M"rced or Tuolwnregroves. Others did not learn of their find since Walker's group failed to report their discovery. -

René Voss – Attorney at Law 15 Alderney Road San Anselmo, CA 94960 Tel: 415-446-9027 [email protected] ______

René Voss – Attorney at Law 15 Alderney Road San Anselmo, CA 94960 Tel: 415-446-9027 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ March 22, 2013 Sent to: [email protected] and [email protected] Penelope Shibley, District Planner cc: Ara Marderosian Kern River Ranger District Georgette Theotig P.O. Box 9, 105 Whitney Road Kernville, CA 93238 Subject: Lower Kern Canyon and Greenhorn Mountains Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) Restoration Project EA Comments for Sequoia ForestKeeper & Kern-Kaweah Chapter of the Sierra Club Ms. Shibley, Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the proposed Lower Kern Canyon and Greenhorn Mountains Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) Restoration Project EA. Sequoia ForestKeeper (SFK) and the Kern-Kaweah Chapter of the Sierra Club (SC) are generally supportive of efforts to close or restore areas damaged by OHVs to avert erosion, to deter illegal uses, to protect natural resources, and to reduce user conflict with non-motorized uses. Purpose and Scope of the Project The Lower Kern Canyon and Greenhorn Mountains Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) Restoration Project would implement the closure and restoration of non-system routes within four recreation sites, relocate and restore campsites located within a recreation site (Evans Flat), and reroute portions of two OHV trails; one mile of the Woodward Peak Trail (Trail #32E53) and two miles of the Kern Canyon Trail (Trail #31E75). Three of the four recreation sites (Black Gulch North, Black Gulch South and China Garden) and one of the OHV trails (Kern Canyon Trail #31E75) are located in the Lower Kern Canyon. The fourth recreation site and the second OHV trail (Woodward Peak Trail #32E53) are located within the Greenhorn Mountains near Evans Flat Campground. -

Giant Sequoia National Monument Management Plan 2012 Final Environmental Impact Statement Record of Decision Sequoia National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Giant Sequoia Forest Service Sequoia National Monument National Forest August 2012 Record of Decision The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Giant Sequoia National Monument Management Plan 2012 Final Environmental Impact Statement Record of Decision Sequoia National Forest Lead Agency: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region Responsible Official: Randy Moore Regional Forester Pacific Southwest Region Recommending Official: Kevin B. Elliott Forest Supervisor Sequoia National Forest California Counties Include: Fresno, Tulare, Kern This document presents the decision regarding the the basis for the Giant Sequoia National Monument selection of a management plan for the Giant Sequoia Management Plan (Monument Plan), which will be National Monument (Monument) that will amend the followed for the next 10 to 15 years. The long-term 1988 Sequoia National Forest Land and Resource environmental consequences contained in the Final Management Plan (Forest Plan) for the portion of the Environmental Impact Statement are considered in national forest that is in the Monument. -

Frontispiece the 1864 Field Party of the California Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC ROAD GUIDE TO KINGS CANYON AND SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARKS, CENTRAL SIERRA NEVADA, CALIFORNIA By James G. Moore, Warren J. Nokleberg, and Thomas W. Sisson* Open-File Report 94-650 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. * Menlo Park, CA 94025 Frontispiece The 1864 field party of the California Geological Survey. From left to right: James T. Gardiner, Richard D. Cotter, William H. Brewer, and Clarence King. INTRODUCTION This field trip guide includes road logs for the three principal roadways on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada that are adjacent to, or pass through, parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (Figs. 1,2, 3). The roads include State Route 180 from Fresno to Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon Park (the Kings Canyon Highway), State Route 198 from Visalia to Sequoia Park ending near Grant Grove (the Generals Highway) and the Mineral King road (county route 375) from State Route 198 near Three Rivers to Mineral King. These roads provide a good overview of this part of the Sierra Nevada which lies in the middle of a 250 km span over which no roads completely cross the range. The Kings Canyon highway penetrates about three-quarters of the distance across the range and the State Route 198~Mineral King road traverses about one-half the distance (Figs. -

Cultural Resources and Tribal and Native American Interests

Giant Sequoia National Monument Specialist Report Cultural Resources and Tribal and Native American Interests Signature: __________________________________________ Date: _______________________________________________ The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14 th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Giant Sequoia National Monument Specialist Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Current Management Direction ................................................................................................................. 1 Types of Cultural Resources .................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) A v ; n Wii UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC GENERALS' HIGHWAY STONE BRIDGES AND/OR COMMON CLOVER CREEK BRIDGE, MARBLE FORK (LODGEPOLE) BRIDGE LOCATION STREET & NUMBER N/A AT ,• /' \ —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN JVi .-.-••-.' •'" "• - . CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Sequoia National Park JL VICINITY OF Lodge-pole 17th STATE CODE COUNTY California 06 Tulare CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.D I STRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE. _MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH __WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL _PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS. (If applicable) National Park Service, Western Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 450 Golden Gate Avenue, Box 36063 CITY. TOWN STATE San Francisco VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Tulare County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER Mineral King and Mooney Boulevards CITY. TOWN STATE Visalia California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Generals Highway Stone Bridges Historic District contains two stone and concrete highway bridges erected in 1930-1931. The bridges, which cross the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River and Clover Creek, are both a part of the grade of the Generals' Highway. -

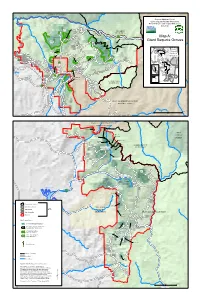

Map A: Giant Sequoia Groves

SIERRA NATIONAL FOREST K Sequoia National Forest i ng s Ri ve r Giant Sequoia National Monument Final Environmental Impact Statement July 2012 Boole Indian Tree Basin MONARCH WILDERNESS Converse Basin Map A: Monarch Chicago Giant Sequoia Groves Stump Hume Evans Complex Agnew Sierra National Forest Kings Canyon Giant Sequoia National Deer National Forest Park Sequoia Cherry Gap Meadow National Abbott Creek Monument Sequoia Bearskin National Park Inyo Grant National Visalia Landslide ! Forest Big Sequoia Porterville Sequoia National ! National Forest Stump Forest Monument Redwood Roads Mountain " JENNIE LAKES 0 50 100 200 300 400 500 Miles Bakersfield ! WILDERNESS SEQUOIA AND KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS er Ri v eah w a K rk Fo t h Nor 0 1.25 2.5 5 Miles SEQUOIA AND KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS Dillonwood INYO Maggie NATIONAL Upper Mountain Tule FOREST Silver Creek Middle er iv Tule R le Burro Creek u GOLDEN TROUT T k Mountain Home WILDERNESS r o State Forest F h t r o Mountain N Home L i t tl e K e r n Rive Wishon r Alder Creek Bush Tree Camp Nelson Freeman Creek Springville Belknap Complex r e v i Black R Mountain Ponderosa Lake Success Tu l e Redhill Sequoia National Forest Peyrone Other National Forest TULE RIVER Land National Park Status INDIAN Other Ownership RESERVATION SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST Monument South Peyrone Giant Sequoia Groves Grove (Administrative Boundary) Johnsondale Freeman Creek Grove Administrative Boundary (Alternatives C & D) Long Meadow Cunningham Grove Influence Zone (Alternatives A & E) Starvation Grove Zone of Influence Complex (Alternatives B & F) Packsaddle Named Sequoia Powderhorn Tree K e r n R i v e r California Hot Springs Wilderness Boundary Main Road River / Stream Deer Creek SOURCE: USDAFS, Sequoia National Forest, 2012 e Riv e r h it DISCLAIMER: This product is reproduced from W geospatial information prepared by the USDA Forest Service. -

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Accessibility Guide

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SEQUOIA & KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Accessibility Guide Kirke Wrench Alison Taggart-Barone Kirke Wrench Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Accessibility Guide Table of Contents Welcome ...........................................................................................4 Where to Find Information .............................................................4 Contact Information ........................................................................5 Obtaining an Access Pass ................................................................7 Service Animals ................................................................................7 For People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing ..............................8 For People Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired ............................9 For People with Limited Mobility .................................................10 The Foothills Area of Sequoia National Park ...............................15 The Giant Forest & Lodgepole Areas—Sequoia National Park ...20 The Grant Grove Area of Kings Canyon National Park ...............28 The Cedar Grove Area of Kings Canyon National Park ...............33 The Mineral King Area of Sequoia National Park ........................37 Welcome Welcome to Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks! This guide highlights accessible services, facilities, and activities. In the first section, you will find general accessibility information to help plan your visit. -

Sequoia National Forest Special Areas

SEQUOIA CONTENTS Hume Hazard Tree Project Appeal Winter Celebrations Nature Explorations Fire What is it Good For FORESTKEEPER® Meet the SFK Staff History of the Sierra Nevada Sierra Nevada Habitats E-UPDATE Sequoia NF Special Areas Hot Links Adopt a Sequoia December 2013 SFK Facebook Page Donate Hume Hazard Tree Project Appeal “No portion of the monument shall be considered to be suited for timber production, and no part of the monument shall be used in a calculation or provision of a sustained yield of timber from the Sequoia National Forest. Removal of trees, except for personal use fuel wood, from within the monument area may take place only if clearly needed for ecological restoration and maintenance or public safety.” Page 3, paragraph 7. Giant Sequoia National Monument Presidential Proclamation Here we go again. Sequoia National Forest continues to operate as though the monument was never declared, so to keep them honest, Sequoia ForestKeeper®, the Kern-Kaweah Chapter of the Sierra Club, and the John Muir Project of Earth Island Institute have been forced to bring suit against a project that appears to go way overboard in trying to justify more logging masked as a “Hazard Tree” project. While there are occasional trees that need to be removed to protect public safety, declaring 2,000 CCF of wood for the project seems like just more of the same. http://www.sequoiaForestKeeper®.org/SFK-SC-JMP_Hume_Hazard_Appeal_Final.pdf May Nature Be a Part of Your Winter Celebrations The sun filters through the magnificent forest. Breathe deep the crisp air as it fills your nostrils with the scent of pine, reminding of holiday seasons gone by. -

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (PDF)

A fact sheet from 2017 iStockphoto Sequoia and Kings Canyon’s 800- mile trail network accounts for $18.4 million of the parks’ $162 million repair backlog. Jim Brandenburg/Minden Pictures/Getty Images Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks California Overview Size and scale are what make Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks unique. They are home to the largest trees in the world and the highest peak in the contiguous United States. Congress established Kings Canyon in 1940, followed by Sequoia in 1980. Today, the two are jointly managed due to their geographic proximity in California’s Sierra Nevada. The parks extend from low-lying foothills through giant sequoia groves and across deep canyons to the crest of the Sierra Nevada. Together, they encompass 865,964 acres of land—nearly all of it wilderness. In this vast area, a backpacker can hike to a spot that is farther from a road than any other place in the contiguous United States. That said, road networks give visitors access to famed attractions such as the Giant Forest and Grant Grove. Unfortunately, these two iconic parks are burdened by more than $160 million in deferred maintenance. Maintenance challenges As is the case in many national parks, Sequoia and Kings Canyon’s transportation system requires most of the repairs. Indeed, the two parks’ paved roads, bridges, and parking lots account for over half of their maintenance backlog. Generals Highway has the highest repair costs, with $43.6 million needed for reconstruction and repaving. The historic roadway serves as an artery connecting destinations such as Grant Grove Village, General Sherman Tree, and Giant Forest Museum yet is listed in poor condition. -

Military Overflight Management and Education Program— Immersion and Communication

Military Overflight Management and Education Program— Immersion and Communication Gregg D. Fauth, Wilderness Coordinator, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, 47050 Generals Highway, Three Rivers, CA 93271; [email protected] Park background Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (SKCNPs) are in the southern Sierra Nevada of California and contain some 865,000 acres of land ranging from foothill to alpine environ- ments. Twelve of the fifteen 14,000-foot-high (4267m) peaks in California are contained within these High Sierra parks, including the highest peak in the lower 49 states, Mt. Whitney at 14,495 ft. (4418m) elevation. The parks are very popular for backpacking and recreational stock use, hosting some 30,000 annual wilderness visitors spending some 100,000 nights camping in the parks’ wilderness. Sequoia and General Grant national parks (NPs) were established in 1890. These parks were: “set apart as a public park, or pleasure ground, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” and to “provide for the preservation from injury of all timber, mineral deposits, nat- ural curiosities or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural state.” Gen- eral Grant NP later evolved and expanded to become Kings Canyon NP in 1940 when its purpose was stated as: “That in order to insure the permanent preservation of the wilderness character of the Kings Canyon National Park, the Secretary of the Interior may limit the char- acter and number of privileges that he may grant within the Kings Canyon National Park.” The passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964 included a directive to the Secretary of In- terior to survey park land for wilderness designation. -

Sequoia National Monument Complaint

1 Patrick Gallagher (CA Bar No.146105) Sierra Club 2 85 Second Street San Francisco, CA 94104 3 (415) 977-5709 (415) 977-5793 FAX 4 [email protected] 5 Attorney for Plaintiffs Sierra Club and 6 Tule River Conservancy 7 Additional Counsel listed on next page 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 SIERRA CLUB, TULE RIVER ) CONSERVANCY, SIERRA NEVADA ) 11 FOREST PROTECTION CAMPAIGN, ) Case No.: EARTH ISLAND INSTITUTE, SEQUOIA ) 12 FORESTKEEPER, and CENTER FOR ) BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, non-profit ) 13 organizations, ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY 14 ) AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Plaintiffs, ) 15 ) (Administrative Procedure Act Case) v. ) 16 ) DALE BOSWORTH, in his official capacity ) 17 as Chief of the United States Forest Service, ) JACK BLACKWELL, in his official ) 18 capacity as Regional Forester, Region 5, ) United States Forest Service, KENT ) 19 CONNAUGHTON, in his official capacity ) as Deputy Regional Forester, Region 5, ) 20 United States Forest Service, ARTHUR ) 21 GAFFREY in his official capacity as Forest ) Supervisor, Sequoia National Forest, ) 22 UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE, an ) agency of the U.S. Department of ) 23 Agriculture, MIKE JOHANNS, in his ) official capacity as Secretary of the U.S. ) 24 Dept. of Agriculture, and UNITED STATES ) DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, ) 25 ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT 1 Eric E. Huber, (Colo. Bar No. SC 700024) Pro Hac Vice Application Pending Sierra Club 2 2260 Baseline Road, Suite 105 Boulder, CO 80302 3 (303) 449-5595 4 (303) 449-0740 FAX [email protected] 5 Attorney for Plaintiffs 6 Sierra Club and Tule River Conservancy 7 8 Deborah Reames (CA Bar No.